Cuba

Vejez

Demografía

Migración

Ancianos

Crisis económica

Natalidad

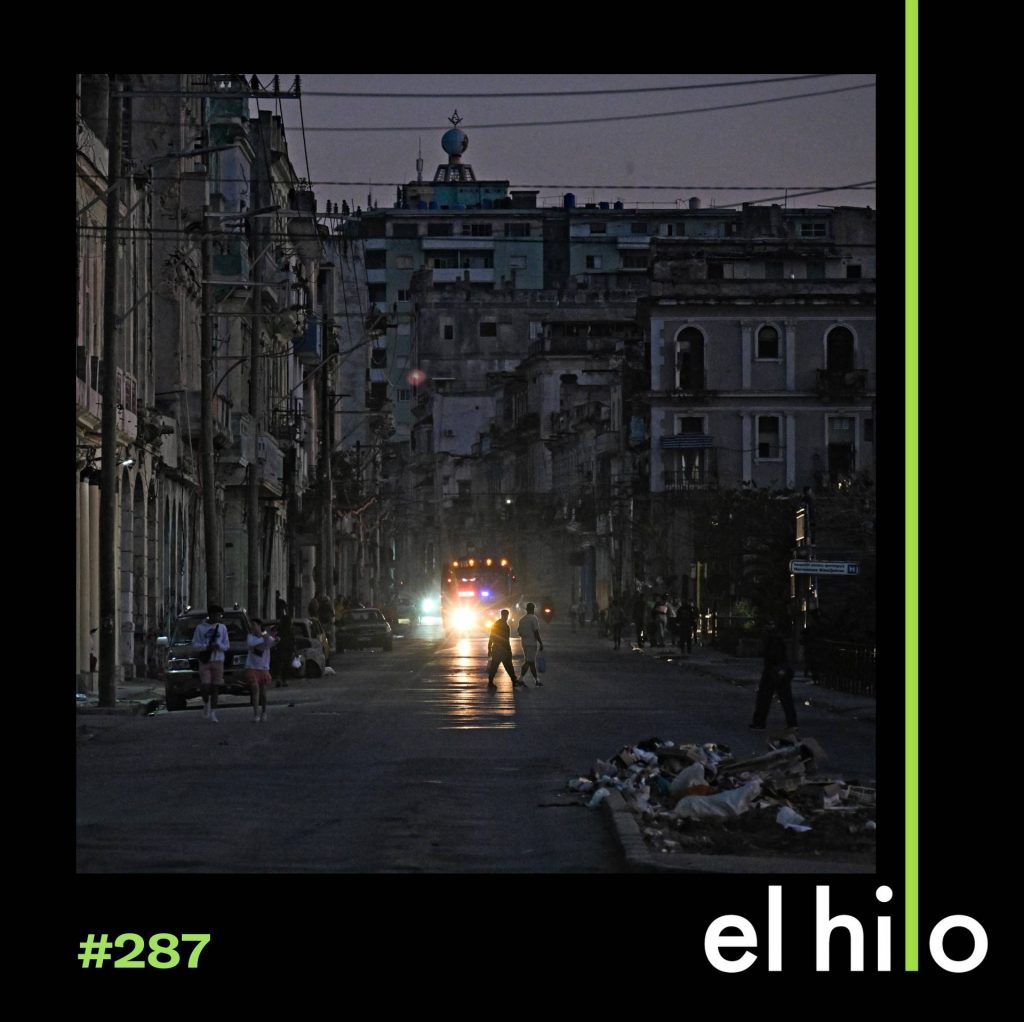

Revolución

Cuba es uno de los países más envejecidos de América Latina y el Caribe. Un cuarto de la población tiene más de 60 años, y los adultos mayores son el único grupo demográfico que crece. Entre el éxodo migratorio, la crisis económica y la escasez de alimentos y medicinas, la vejez de los cubanos multiplica los desafíos que viven los jubilados en otros países del continente. Nuestra productora Mariana Zúñiga viajó a La Habana para entender cómo es envejecer en este contexto para la generación que dedicó su juventud a la revolución cubana, y qué les dejó esa experiencia del pasado para vivir este presente.

Este episodio se produjo con el apoyo de Civil Rights Defenders, una organización que lleva 40 años trabajando por la defensa de derechos civiles y políticos en los lugares más represivos del mundo.

Créditos:

-

Producción y reportería

Mariana Zúñiga -

Edición

Eliezer Budasoff, Silvia Viñas -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción en redes sociales

Samantha Proaño, Franklin Villavicencio, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Elías González, Remi Lozano -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

Fotografía

Getty Images / Yamil Lage

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Inés Casal: Bueno, hemos sido olvidados porque aquí los que vivimos peores somos los viejos, los de aquella generación que seguimos viviendo aquí.

Eliezer Budasoff: Ella es Inés Casal, es cubana, profesora jubilada y tiene 77 años.

Silvia Viñas: Cuando Inés habla de “aquella generación”, se refiere a la que vio nacer a la revolución cubana. Los que en 1959 apenas eran niños y adolescentes. Es la generación que, al crecer, se involucró de alguna u otra manera en la revolución.

Inés: Todos estábamos muy felices de poder participar en un proyecto que nos parecía un proyecto muy bueno, un proyecto que había dado educación ─a mí no me gusta decir gratuita, porque realmente nada es gratuito─, educación pública, también salud pública. Y muchísimas otras cosas, sobre todo para las personas más vulnerables, para las personas más pobres. Yo me involucré en eso y lo hice a conciencia, de corazón.

Eliezer: Con la idea de construir una sociedad nueva. Cosecharon en el campo, cortaron caña de azúcar, enseñaron a cientos de campesinos a leer y escribir. Y hasta pelearon en guerras fuera de Cuba.

Inés: Fueron de jóvenes a Angola, a luchar en otro país que no era el suyo. A nadie se le ocurría decir que no, muchos aquí, que lucharon en Angola y que están ahora muriéndose, prácticamente en las calles.

Silvia: Y no sólo los veteranos que pelearon en Angola. En Cuba, en general, la vejez es una etapa llena de carencias y precariedad.

Inés: Algunos andan revisando los tanques de basura para ver si encuentran algo para vender. Lo que sea que puedan vender para poder sobrevivir. Yo creo que lo más difícil es sentirse que uno es muy vulnerable. A mí la palabra vulnerabilidad no me gusta, pero bueno, es la única que encuentro en estos momentos. Que uno se siente solo. Aquí hay muchos ancianos que están solos.

Inés: Aquí prácticamente no hay asilos para ancianos. No hay. Los que hay no alcanzan para los ancianos. Aquí no hay ningún apoyo especial. Las jubilaciones son irrisorias, o sea, las jubilaciones no te alcanzan para nada. En estos momentos mi jubilación subió a 1.625 pesos. Un cartón de huevos te cuesta 3.000 pesos. O sea, por supuesto que los que están peor son los jubilados.

Eliezer: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Estudios. Soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: Y yo soy Silvia Viñas.

Cuba es uno de los países más envejecidos de América Latina y el Caribe. Un cuarto de la población es mayor de 60 años. Se espera que esa cifra aumente, y que para el 2030, un tercio de los cubanos en la isla tengan más de 60 años.

Eliezer: Entre la falta de comida y medicinas y el exilio de sus familiares, muchos llegan a la tercera edad con la sensación de que les han roto una promesa. Hoy: cómo es la vejez para la generación que entregó sus años de juventud a la revolución cubana.

Es 23 de enero de 2026.

Silvia: Nuestra productora Mariana Zuñiga nos sigue contando.

Mariana Zúñiga: Cuando empezó la Revolución cubana, Inés tenía 11 años recién cumplidos. Recuerda que la llegada de Fidel Casto al poder le generó ilusión a la mayoría de la gente que conocía.

Inés: Yo tendría que decirte que en esos primeros años, yo no sabía muy bien lo que iba a pasar, y yo empecé a conocer a través de mi hermano, que sí se involucró muy rápidamente ─en el año 60 en las milicias─, yo realmente hasta la universidad, yo no creo que yo haya sido ni revolucionaria ni nada. A mí lo único que me interesaba era estudiar.

Mariana: Inés estudió química en la Universidad de la Habana, pero no sólo estudiaban matemáticas o las características de la tabla periódica. Combinaban la educación formal con el trabajo en el campo. Todo esto en apoyo al proyecto revolucionario. La idea de que su generación tenía la responsabilidad de consolidar la revolución era algo que les reforzaban constantemente en la escuela.

Inés: Sí, eso era como parte del currículum. O sea, yo entré en octubre, más o menos, del 66 y ya en abril nos fuimos para allá, en una provincia que se llama Sancti Spíritus, a recoger cebollas, etc. Eso era parte del currículum. En ese caso fueron 35 días. Allí había que ir. O sea, es que a nadie se le ocurría pensar que era ni obligatorio, ni voluntario. Era algo que era parte de. Y además lo hacían todos tus compañeros. Entonces todo eso entusiasmaba a una juventud que quería sacar adelante el país.

Mariana: Para entrar en la Unión de Jóvenes Comunistas, Inés tuvo que mentir. Y es que la primera vez que trató, la rechazaron por creer en Dios y por tener una hermana en Estados Unidos. Eso la hacía apátrida y traidora.

Inés: Quería yo entrar en la Unión de Jóvenes Comunistas. Admiraba a los compañeros míos que estaban en eso, los admiraba tremendamente y además me parecía que siendo de la juventud comunista, yo podía ayudar más a la Revolución y al país. Y con relación a mi hermana, era cierto que ya yo sí dejé de escribirle. Y así entré yo en la Juventud.

Mariana: Con el tiempo, Inés aprendió a no mencionar más a su hermana. A no pensar en ella. Dice que aún no ha podido superar totalmente lo cobarde que fue al renunciar a esa relación.

Inés: Por supuesto, pasaron los años y me fui decepcionando bastante, pero era muy difícil uno tomar la decisión de decir “me voy del partido”.

Mariana: Inés describe su decepción como un proceso lento. Lento pero continuo. Como una gota de agua que perfora una piedra de a poco. Para ella, que fue profesora, sus estudiantes fueron clave para darse cuenta de que el modelo no funcionaba como le habían prometido.

Inés: Ellos me ayudaron mucho. Mis hijos, los estudiantes, los hijos de mis amigos, fueron los que me emplazaban a que yo, cuando quería explicarles algo, yo me daba cuenta que yo no tenía argumentos para rebatir lo que ellos me estaban diciendo. Me daba cuenta que mis argumentos no los convencían a ellos.

Mariana: Así como pasó con Inés, muchas otras personas de su generación también se decepcionaron con el proyecto. Su hermano, por ejemplo, que fue teniente coronel, cuando se jubiló no recibió ningún tipo de ayuda por parte del régimen. Tampoco una condecoración o felicitación por todos sus años de servicio. Inés dice que su vejez fue muy triste. Estaba muy enfermo y en sus últimos momentos, ni sus colegas ni las instituciones para las que trabajó le dieron una mano. Murió olvidado. Tanto por su esposa, que lo dejó sólo cuando migró a Estados Unidos, como por la revolución, a la que dedicó todas sus energías y sacrificio.

Inés: Aquí no hay ningún… Nada, nada, nada que sea a favor de las personas mayores, de los ancianos, nada. Yo te lo puedo decir, Mariana, que no.

Mariana: Inés ha pasado años reflexionando sobre este tema y se ha hecho un montón de preguntas: si su generación fue ingenua, si fue cobarde, si los convencieron o los manipularon, si es que son culpables o víctimas.

Inés: Culpa sí yo siento. No una culpa que me remuerde la conciencia, no. Es una culpa que yo la entiendo. Es una culpa de no haber despertado a tiempo. Es una culpa de haber sido a lo mejor ingenua, de haber sido demasiado cándida, demasiado… Pero eso no lo puedo borrar. Pero después me di cuenta con el tiempo que si yo no había despertado en aquellos momentos. Ahora que ya yo sí estaba despierta, yo debía dejar mi testimonio. Yo he escrito varias cosas relacionadas con mis testimonios personales, con las cosas que yo vi y lo seguiré haciendo, lo seguiré haciendo mientras pueda.

Mariana: Inspirada por su experiencia y la de otros, Inés escribió un cuento y lo envió a la plataforma Cuido60, un proyecto que busca difundir información sobre el envejecimiento en Cuba. Así conocí su historia.

Inés: Yo le mandé mi experiencia muy breve, quién yo era, etc. Y bueno, lo que yo pensaba de la desilusión que uno sufrió a lo largo de estos años, ¿no?

Mariana: El cuento se titula: “La vejez que nunca esperamos”. Ganó un concurso y ahora es parte de un libro sobre la vejez en Cuba.

Inés: Por supuesto, era un paraíso lo que nos vendieron. Nosotros no pensábamos en ser millonarios. Pensábamos en que debía de ser un país con todos y para el bien de todos, que era lo que nos decían. O sea, yo no soñaba con ser una persona que viajara por el mundo ni nada de eso, sino de tener una vejez tranquila, en un lugar donde yo tuviera lo mínimo indispensable. ¿Entiendes? Fue lo que yo soñé. Por supuesto que no lo tenemos. No lo tiene nadie. No es que no lo tengamos nosotros, no lo tiene nadie aquí en este país. Yo no esperé nunca esta vejez.

Mariana: Cuando estuve en La Habana, visité una institución que dirige la Iglesia Católica en el centro de la ciudad, en un edificio antiguo. Allí funcionan diferentes proyectos sociales. Yo fui para conocer Otoño, una iniciativa que busca mejorar la calidad de vida de los adultos mayores en la ciudad. Dan clases, charlas, y una vez al mes hacen una gran fiesta de cumpleaños. Ese día estaban celebrando a todas las personas que cumplieron entre diciembre y enero. Yo llegué justo para cantar “Felicidades”, la canción tradicional de cumpleaños en Cuba.

Coro: Uno, dos, ¡Tres! Felicidades amigo en tu día que lo pases con sana alegría, muchos años de paz y armonía. Felicidad, Felicidad, Felicidad.

Coordinadora: Ya vayan sentándose poco a poco. Entonces ahora…

Mariana: Después de cantar, todos se sentaron en círculo y la coordinadora invitó a los cumpleañeros a pararse uno a uno, presentarse y contar algo sobre ellos mismos.

Nancy: Nancy de los Ángeles, nací el 27 de enero del 53. Tengo 72 años y me gusta que me canten “Felicidades”.

Coordinadora: ¿Otra cumpleañera?

Mariana: Se pararon a hablar unas ocho personas. Todas mujeres. Y casi de última, tímidamente, se paró Laura, una señora que visita el centro desde hace poco.

Laura: Me llamo Laura, nací el cuatro de diciembre.

Mariana: No queda muy claro por la calidad del audio, pero Laura dice que está tratando de socializar porque no conoce mucha gente. Entonces, hacer amigos es su principal motivación para venir al centro.

Mariana: Cuando terminó la fiesta, la busqué para hablar.

Laura: Mi nombre es Laura González Otero. Tengo 74 años.

Mariana: Estudió geografía en la Universidad de La Habana y trabajó en la Academia de Ciencias toda su vida.

Laura: Soy investigadora. Hice candidaturas, doctorados, cosas de esas. Ya todo eso pasó y ahora estoy jubilada en mi casa.

Mariana: ¿Y tienes hijos? ¿Tuviste hijos?

Laura: Tuve un hijo que murió. No tengo familia aquí en Cuba. No tengo ninguna familia en Cuba.

Mariana: A diferencia de la mayoría de los cubanos que hoy viven las consecuencias de una larga crisis económica, Laura dice que ella no tiene problemas de dinero.

Laura: Porque tengo unos sobrinos maravillosos que ellos solos me mantienen.

Mariana: Le mandan dinero desde afuera. Realmente un problema es otro.

Laura: Me pasa que no tengo red de apoyo.

Mariana: Laura vive sola en un apartamento. En los últimos años, ha tenido períodos en los que se ha sentido realmente sola. Su esposo falleció, y a medida que la situación empeoraba sus seres queridos se fueron de la isla: sus vecinos, sus amigos y el resto de su familia. Uno a uno.

Laura: Mi sobrina se casa y se va para Inglaterra. Mi sobrino se casa y se va para Bilbao. Mi hermano y mi cuñada se fueron. O sea, empezó a irse mi gente. Mi amiga, esa amiga de toda la vida, desde jovencita, que estudiamos juntas en la Alianza antes de entrar a la universidad. Esa amiga se me fue. Después otra que yo fui tutora de ella también. O sea, cuando vienes a ver no tengo a nadie de hace más de tres años que yo conozca aquí.

Mariana: Una vez leí que Cuba es el país del adiós infinito, donde la gente nace, crece y migra. Y aunque la migración no es un fenómeno nuevo para los cubanos, los expertos dicen que Cuba está viviendo un éxodo masivo. El más grande de su historia. Desde el 2021, mucha más gente comenzó a salir del país por diferentes motivos: el colapso de la economía, la escasez, la crisis de salud, los constantes apagones, la caída del sector turístico y la represión política. Todos estos factores han vaciado el país. Por años, la población de Cuba rondaba las 11 millones de personas. Hoy, viven en la isla un poco más de ocho millones. Es decir, en apenas cuatro años, la población cubana cayó un 24%. La crisis migratoria afecta profundamente la vida de las personas mayores, como Laura. Padres, tíos y abuelos que se quedan solos en Cuba.

Laura: Porque hay una generación que falta, que es la generación de mis sobrinos. Gente de 30 y pico, 40. Esa gente no está en Cuba, ni están los hijos de ellos tampoco. ¿Te das cuenta? Falta gente.

Silvia: Hacemos una pausa, y a la vuelta: cómo enfrentan la vejez los cubanos y cubanas como Laura que se han quedado en la isla sin una red de apoyo. Ya volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta. En Cuba, la mayoría de los adultos mayores viven solos, especialmente las mujeres. Como Laura, hay miles en todo el país, pero la mayoría están en La Habana, uno de los lugares más envejecidos de la isla. Mariana nos sigue contando.

Mariana: La soledad ha puesto a Laura en situaciones muy complejas, sobre todo con su salud. Recuerda la vez que tuvo que operarse de cataratas. Justo coincidió con el comienzo de la pandemia

Laura: El día que cerraron fue sábado, yo ingresaba el martes para operarme de los ojos. Estaba la catarata, que se yo, planificado y me pasé la pandemia ciega en mi casa. Eso fue terrible.

Mariana: En tres años la operaron cinco veces. Tres en el ojo derecho, pero solo dos en el izquierdo.

Laura: Que por eso este lo tengo así caído, porque la tercera no lo quise hacer. Y entonces, me pasó esto del corazón.

Mariana: En 2024, Laura se empezó a sentir mal. Cuando fue al médico, le dijeron que su corazón estaba fallando de nuevo. Ya había tenido un infarto hace unos años. El doctor sugirió ponerle un marcapasos. Y aunque sus sobrinos le mandaron el costoso aparato desde España, era como un déja vu. Tendría que pasar nuevamente por todo el proceso post operatorio sola. Pero esta vez tuvo más suerte. Dos días antes de la operación, una nueva vecina ofreció ayudarla.

Laura: Ella me acompañó el día de la operación. Ella me llevó ropa, me llevó comida, esas cosas. Y después, cuando salí del hospital, ella me ayudó. Ella dejó de trabajar esos días y yo le tuve que dar dinero para que viviera. Pero ella se portó muy elegante conmigo y muy buena.

Mariana: Después de recuperarse, decidió que algo en su vida tenía que cambiar.

Laura: Estoy tratando de buscar algo que me anime que me…

Mariana: Que la saque de la casa, del silencio. Que la lleve a escuchar el ruido de la calle, a encontrarse con gente. Y así fue que encontró el proyecto Otoño, el espacio cultural y educativo para los adultos mayores de La Habana donde la conocí.

Laura: Y vengo aquí porque me di cuenta que yo estaba totalmente aislada. Entonces empecé a hacer un curso de psicología positiva y entonces empecé ahí. Después entré en uno de telefonía móvil. Y entonces vengo y socializo. Tengo amistades ahí.

Mariana: Y ahora que estás viniendo y conociendo gente. ¿Cómo te sientes? ¿Sientes que te ha ayudado en algo?

Laura: ¡Cómo no! Tengo relación, por lo menos me relaciono con gente. Gente que tiene mi historia. Porque tengo, por ejemplo, vecinos. Pero las historias de mis vecinos no son las mías. Cada uno tiene sus vidas, sus cosas, que los vecinos son los familiares más cercanos para determinadas cosas, pero no son personas con las que tú tienes afinidad. Entonces, cuando tú ves una vieja que tiene tus mismos cuentos, tú misma historia, que estuvo en las mismas… o sea, es otra cosa.

Mariana: En este centro, Laura ha encontrado compañía y atención. Cuidados que, de otra manera, no hubiese recibido porque el sistema de cuidados que ofrece el régimen es ineficiente, está roto. Recordemos que Cuba tiene una de las poblaciones más envejecidas de América Latina, y se espera que para el 2050, Cuba sea el noveno país más viejo del mundo. Esto es un problema y el estado lo sabe.

Audio de archivo, presentador: La atención a la dinámica demográfica es una prioridad para el gobierno cubano.

Audio de archivo, periodista: Por lo que tienen preferencia, igualmente, los programas de fecundidad y el programa materno infantil.

Mariana: Estos programas tienen como fin estimular la natalidad, sea ofreciendo un mayor cuidado a las embarazadas y a los recién nacidos, o apoyando a las familias que tienen más de dos hijos. El Centro de Estudios Demográficos de la Universidad de La Habana también cree que la única opción para lidiar con el aumento de la vejez es que nazcan más personas en la isla. Pero esta solución es muy difícil de alcanzar. Las cifras muestran que el número de personas menores de 15 años ha bajado. Se reportan más muertes que nacimientos en la isla. Y la tasa de fecundidad de Cuba es la más baja en la región. Es que aquí las mujeres en edad reproductiva son las que más migran. Y muchas de las que se quedan, simplemente no quieren tener hijos. Al menos no en este contexto, como le explicó una madre a un periodista local.

Audio de archivo, mujer cubana: Hoy mismo no había pan para el muchacho ir a la escuela. ¿Cómo usted cree que uno va a seguir pariendo? No se puede parir.

Mariana: Además, el problema con estas políticas de natalidad es que no resuelven el problema principal: la falta de atención y los cuidados para los mayores. No hay suficientes casas de ancianos, ni programas estatales, ni un sindicato exclusivo para atender a los jubilados. Entonces, la situación en la isla hace que envejecer sea aún más complicado que en otros países.

Laura: Los cubanos vivimos mucho, porque hubo una época que la salud pública fue buena y era un banderín político. O sea, hubo mucha vacunación, mucha atención médica. Ahora no la hay. Ahora todo es complicado, Ahora es como que no funciona. No hay medicinas. Yo necesito seis medicinas todos los días. Ninguna la hay en la farmacia. Yo tengo un tarjetón que dice que a mí me tienen que dar esa medicina en la farmacia y hace tres meses que no viene ninguna de las medicinas.

Mariana: Tampoco es fácil encontrar insumos como agujas o reactivos para hacer análisis clínicos sencillos. Esto, muchas veces, impide que los ancianos puedan tener un diagnóstico a tiempo. La escasez se ha convertido en un problema crónico. Más del 70% de los medicamentos esenciales no están disponibles en las farmacias. Para conseguirlos, hay que ir al mercado informal o a las redes sociales, donde se compran, venden o intercambian medicinas. Eso sí, a precios súper altos.

Laura: Entonces yo lo compro. ¿Por qué? Porque tengo dinero que me mandan mis sobrinos. Los dos matrimonios me mantienen. Ellos cada uno hacen como si fuera una competencia. A ver quién me manda más cosas y quién lo manda más, quién ayuda más. Es una cosa muy linda, pero a mí me duele mucho, porque yo trabajé toda mi vida. Toda la vida trabajé. Ahora estoy jubilada y yo gano 1.528 pesos de jubilación. Que con 1.528 pesos tú no haces nada.

Mariana: Eso es más o menos cuatro dólares. Y cada día el valor de su pensión baja por la inflación. Cuando la conocí, ese monto sólo le alcanzaba para comprar unos tres kilos de arroz y menos de un kilo de tomates. En julio hubo un aumento en las pensiones y jubilaciones, pero realmente sigue sin alcanzar para cubrir las necesidades básicas.

Laura: Y te digo, soy una vieja súper privilegiada.

Mariana: Laura está muy consciente de sus privilegios. Ella sabe que los jubilados que no tienen apoyo económico de su familia la pasan muy mal en Cuba. Aquí las personas mayores son las más vulnerables y las más afectadas por la crisis económica.

Laura: O sea, estás tocando el fondo, pero el fondo siempre te lo bajan más. Eso es muy duro. Entonces tú vives además en un surrealismo y en una esquizofrenia, porque tú oyes al televisor decirte que todo está muy bien, que todo es una maravilla y que nosotros somos, ¡vaya!. Entonces tú oyes una cosa y estás viviendo otra.

Mariana: Los sobrinos de Laura le han ofrecido varias veces ayudarla a salir de Cuba. Llevarla a vivir con ellos. Ella se ha negado. No quiere sentirse una carga. Además, tampoco tiene la fuerza para hacer un viaje así. Dice que ya está muy cansada. A pesar de todo, para Laura nada es eterno. Siente que la situación algún día va a cambiar, pero también sabe que ni ella ni su generación lo verán.

Laura: Los regímenes cambian, se acabó el esclavismo, se acabó la Edad Media. Todo eso se acabó. Pero el problema es que tú nada más que tienes una vida. Tú no estás en un libro de historia, porque el cuento este va a ser, de aquí a 200 años: “en el año 59 triunfó una revolución liberadora no sé qué. Después se fue pa’l comunismo, después llegó a la miseria y en el año tal volvió la democracia”. Son tres párrafos en la historia de Cuba, pero es mi vida completa. Yo tenía ocho años cuando triunfó la Revolución y tengo 74. Mi vida entera está metida en un párrafo de la historia de Cuba.

Mariana: Cuando eras más joven, ¿cómo imaginaste que sería tu futuro y qué tan diferente es eso de lo que imaginaste?

Laura: Yo me imaginaba una película y me llevaron a ver otra. Entonces lo que espere que iba a ser mi vida y la que es, no es, pero no es… No me duele que sea distinta. Lo que me duele es que no tiene sentido. Vivir para durar y no para vivir es muy feo. Estás durando. Yo voy acumulando tiempo, pero yo no vivo, porque esta no es la vida que yo quiero.

Eliezer: A falta de programas estatales, la familia cubana se ha hecho responsable del cuidado de las personas mayores. Hablamos de eso después de la pausa. Ya volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Silvia: En Cuba, la mayoría de los cuidados los hacen las mujeres. Muchas madres, hijas, sobrinas o nietas abandonan sus trabajos para hacerse cargo de sus ancianos. Y es probable que una vez que ellas mismas lleguen a la vejez, sigan cuidando a otros.

Eliezer: Los cuidadores tampoco tienen mucha ayuda o reconocimiento de parte del Estado. Esto no sólo pone en riesgo a la salud de los enfermos, sino también de los mismos cuidadores.

Silvia: Mariana nos sigue contando.

Mariana: Gracias a un amigo conocí a una cuidadora. Su nombre es Irina, tiene 62 años.

Irina: Hola, pasen.

Mariana: Gracias.

Mariana: Irina me recibió en su casa, donde vive con su tío de 82 años. Al llegar, él estaba sentado viendo televisión y ella estaba por hacer un café.

Mariana: Que lindo esto que haces, ¿qué es?

Irina: Sí, son una especie de mandalas, un poco más…

Mariana: Sobre una mesa, cerca de la cocina, estaban a medio terminar las artesanías que hace ella para vender.

Irina: Ahora mismo estaba poniendo un café. ¿A usted no le molestan los gatos?

Mariana: No, me encantan.

Irina: Yo tengo cuatro gatas. A ver, yo soy protectora de neonatos, gatos neonatos. Pero, ahora mismo no tengo el dinero, ni la leche de bebé…

Mariana: A Irina siempre le gustaron mucho los animales. Esto es algo que heredó de su tío.

Irina: Mi tío es biólogo, biólogo marino y eso hizo también que yo… porque bueno, él hizo la función de padre nuestro y entonces imité eso, lógicamente, por suerte.

Mariana: Pero lo que no adoptó de él fue su ideología política.

Irina: Ellos lo dieron todo. Confiaron en un tipo que se llama Fidel Castro, que era un gran orador, muy inteligente. Y entonces fue engañando a todo el mundo.

Irina: Este país era la gran estafa desde que yo era joven. Imaginate que desde que tú vas a preescolar te dicen: “Tú vas a ser pionero y le va a dar el pionero a él, seremos como el Che”. Entonces todo eso te van politizando. Tus padres también estuvieron politizados, tus abuelos también y te educas y vives así, sin saber nada.

Mariana: Irina dice que a ella no le pasó, que nada de eso le entró en la cabeza. Quizás por ser muy distraída, o por estar viendo bichitos todo el día. Esa idea simplemente no caló en ella.

Irina: Por suerte, como era muy libre, por eso me gustaba toda la historia del rock y del peace and love y todo eso también me fue influenciando mucho, por suerte, y no me até a nada. Como no me até a ninguna religión en específico, porque me gustaba ser libre y de eso me alegro muchísimo.

Mariana: De hecho, me contó que ella nunca se sintió del todo cómoda en Cuba y siempre quiso irse.

Irina: Pero no me fui porque mis padres comenzaron a envejecer, mi mamá y mi tío, y bueno, hasta hoy estoy aquí por ellos. Pero al final me siento bien, porque él me crió. Vivimos gracias a él. Y yo pienso que hay que retribuir.

Mariana: Irina ha pasado gran parte de su vida cuidando a otros. Primero fue a su abuela con cáncer. Luego a su mamá, que murió en 2024 de un derrame cerebral. Y ahora cuida a su tío.

Irina: Bueno, hija, yo al morir mi madre haz de cuenta que ni siquiera yo pude hacer el duelo. Porque al mes y un día, domingo 9 de la noche, veo a mi tío parado aquí en la cocina y cuando yo entro, que veo a mi tío que le pregunto qué le pasa. Ya yo me di cuenta que tenía un infarto cerebral. Te imaginas que él estuvo dos meses hospitalizado. Y cuando yo lo regreso acá, él no estaba, a ver, no caminaba, hablaba poco. No tenía funciones en las manos. Entonces tuve que rehabilitarlo yo. Entonces yo estaba muy deprimida por lo de mi mamá y me costaba un trabajo tremendo.

Mariana: Como la pensión de su tío no alcanza para sobrevivir, Irina empezó a vender sus cosas para poder encargarse de él: de su alimentación, de sus pastillas… Aunque no fue suficiente.

Irina: Yo vendí zapatos, vendí ropa. Vendí cadenas, vendí adornos. A mí no me queda nada. Yo sobrevivo gracias a que tengo amistades que viven en el exterior y me mandan la leche de mi tío. Otra me manda un pollo, porque si no mi tío tiene que almorzar y comer proteína. Si no, se me muere el viejo. Y ahora lo que estoy es trabajando. Hice unos colgantes, lo que sé hacer yo es artesanía. Entonces es lo que estoy intentando ahora para darle a unos amigos, para que me vendan.

Mariana: Irina solía vender sus artesanías en el Paseo del Prado, cerca del centro de la ciudad. Pero ahora ya no hay forma de acomodar su trabajo con el cuidado de su tío, que le ocupa prácticamente todo el día.

Irina: Yo lo despierto ocho de la mañana. En lo que él desayuna, que se asea solito, él da media hora con el andador de vuelta y después con el bastón. Yo termino con él todos los días a las once de la mañana. A esa hora me tengo que poner a hacer cosas, cosas que me salen más lentas porque no soy buena ama de casa, y como no tengo dinero, pues, me tengo que poner a trabajar acá en casa. Entonces con él es muy difícil porque ponme el pato, haz tal cosa. Orina solito, pero igual moja todo porque le tiemblan las manos. Entonces limpias trapitos, lavas y tienes que estar constantemente encima de él. Incluso cuando lo veo muy serio tengo que dejar lo que estoy haciendo y sentarme con él, y eso te va afectando mucho.

Mariana: Irina dice que está sobrecargada mentalmente, que ha bajado casi 20 kilos.

Irina: Tengo una cosa aquí en el ojo, así, que me tiembla el párpado superior una semana. Se me quita, me vuelve. Yo me he visto que vengo para acá y no sé qué voy a buscar, ni sé qué voy a hacer. Y he visto cosas en mí que digo, bueno, estoy jodida. Yo he tenido momentos acá que me he despertado de madrugada con falta de aire, falta de aire que no puedes respirar y eso no es otra cosa que todo el proceso este, que es muy duro y muy desgastante.

Mariana: Ser cuidador tiene un impacto muy profundo en las personas. Irina sufre lo que se conoce como el síndrome del cuidador, un estado de agotamiento físico, mental y emocional que desarrollan los que cuidan de alguien continuamente. Hace mucho que dejó de preocuparse por ella misma. Casi no sale de casa. Ni siquiera va al médico, aún cuando sufre de la presión y la tiroides. Recordemos que tiene 62 años. Ella misma está envejeciendo.

Irina: Envejecer es muy jodido para mí en sentido general. Yo tuve una tía abuela guajira, sabia, se murió como con 90 años, que decía que lo más feo que hay en el mundo es la vejez y la miseria. Claro que nos importa tener esta arruga, esta arruga. Te las comienzas a ver. Ah, que tú dices que estoy más interesante, que no sé qué, perfecto, pero igual es fastidiado. ¿Qué pasa? Que ahí tienes alternativas de una crema o un gimnasio y el estilo de vida y la alimentación, por supuesto, pero en Cuba es terrible, en Cuba, como yo le digo el otro día a una amiga, que a mí nomás me falta el bigote para llamarme Roberto.

Irina: Terminas de bañarte y no tienes una colonia, un perfume, unos aretes, cualquier cosa que te haga sentir bien contigo misma y que te gusta. No la tienes. Envejecer en Cuba es muy, muy jodido. Además, la alimentación. A mí me gusta comer proteína y vegetales. No me gusta el arroz. Pero bueno, tengo que comer arroz como si fuera un chino, porque no hay más nada.

Mariana: ¿Encuentras una buena parte? ¿Encuentras algo positivo?

Irina: Bueno, yo debería decirte que sí, pero no, no se lo encuentro. A ver, yo agradezco todos los días respirar y estar viva y medianamente cuerda, ¿no? De que mi tío está estable. Porque además, yo no tengo dinero para llevarlo a sus consultas médicas. Dejó de ir. Lo trato de alimentar bien. Le checo la presión, sus parámetros. Y hasta ahora lo quiero así. No le duele ni un hueso. Me duele más a mí que él. Agradecida por estar viva y porque sé que hay muchas cosas hermosas que uno puede disfrutar.

Mariana: Durante mi visita a Cuba conocí muchas personas mayores, y sería injusto decir que todas tienen la misma experiencia al envejecer. Algunas, las que pueden ─las que no están tan solas, o tan pobres, o cuidando a alguien— buscan la manera de darle sentido a sus días. De, como dice Irina, encontrar cosas hermosas que puedan disfrutar. Me invitaron a una clase de actuación para adultos mayores en el centro social donde conocí a Laura, la señora que perdió su red de apoyo porque su familia y sus seres queridos se fueron de Cuba. La clase la dirige Enrique, un periodista jubilado, argentino, que vive en Cuba desde hace más de una década.

Profesor Enrique: Bueno, compañeros, vamos a comenzar. Vamos a comenzar porque tenemos el tiempo bastante acotado.

Mariana: Allí encontré un grupo de señoras que hizo del teatro su refugio.

Las vi haciendo ejercicios de respiración.

Profesor Enrique: Y vamos a comenzar por la inspiración con la boca entrecerrada.

Mariana: También improvisaron.

Profesor Enrique: El tema va a ser: aquí estamos, esto somos.

Alumna: Ay madre mía, yo que salí temprano para resolver este problema. Llego a donde están imprimiendo y no hay corriente.

Mariana: Y cantaron.

Profesor Enrique: Música.

Alumna: Si piensas en volver a mi y de nuevo conquistarme…

Mariana: Al final de la clase, me senté a conversar con algunas de las alumnas. Quería saber qué significaba el teatro para ellas en este momento de sus vidas y qué las motivaba a seguir viniendo.

Rosario: Rosario de la Caridad Rodríguez Pérez. 70 y… A uno se le olvida, 74 años. Mira, mi felicidad es tan grande, porque no es que nos sentimos realizados porque estamos actuando y escuchamos los aplausos del público. Eso es maravilloso. Pero lo más maravilloso es que nos están reclamando. Nos vamos a presentar en una escuela de niños especiales. Vamos a actuar para ellos. Nos demandan de una casa de cultura, entonces me siento útil y me siento que le doy felicidad a los demás y no saben ellos que me la estoy dando a mí misma también. Es maravilloso.

Juliana: Mi nombre es Juliana Díaz Ramírez, tengo 74 años, esa energía de sentirse útil, de poder hacer reír a los demás como nosotros lo hacemos en el teatro, pues eso nos fortalece, nos da vida, nos hace feliz.

Xiomara López: Me llamo Xiomara López Padilla, soy fundadora del grupo. Hemos aprendido mucho. Yo nunca pensé que después de haber estudiado, porque a veces uno dice no, porque me lo sé todo, no, en la vida no se sabe todo. He aprendido cosas que me han enseñado aquí y de los mismos compañeros que he conocido. Nos reunimos, cantamos, bailamos y creo que esto es un proyecto precioso y mucha gente se ha retirado y ha encontrado aquí otra vida.

Mariana: Este episodio fue producido y reportado por mí, Mariana Zúñiga, con el apoyo de Eileen Sosin. Lo editaron Silvia, Eliezer y Daniel Alarcón. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido es de Elías González, con música compuesta por él y por Remy Lozano.

Queremos agradecer a Elaine Acosta, Pablo Argüelles y la FLIP, la Fundación para la Libertad de Prensa, por su apoyo en este episodio.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Jesus Delgadillo, Samantha Proaño, Franklin Villavicencio, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Inés Casal: Well, we have been forgotten because here the ones who live the worst are the elderly, those of that generation who are still living here.

Eliezer Budasoff: She is Inés Casal, she’s Cuban, a retired teacher, and she’s 77 years old.

Silvia Viñas: When Inés talks about “that generation,” she’s referring to the one that witnessed the birth of the Cuban revolution. Those who in 1959 were barely children and adolescents. It’s the generation that, as they grew up, got involved in one way or another in the revolution.

Inés: We were all very happy to be able to participate in a project that seemed to us to be a very good project, a project that had provided education—I don’t like to say free, because really nothing is free—public education, also public health. And many other things, especially for the most vulnerable people, for the poorest people. I got involved in that and I did it conscientiously, from the heart.

Eliezer: With the idea of building a new society. They harvested in the fields, cut sugarcane, taught hundreds of peasants to read and write. And they even fought in wars outside of Cuba.

Inés: They went as young people to Angola, to fight in a country that wasn’t their own. It didn’t occur to anyone to say no, many here, who fought in Angola and who are now dying, practically in the streets.

Silvia: And not only the veterans who fought in Angola. In Cuba, in general, old age is a stage full of hardship and precariousness.

Inés: Some go through garbage bins to see if they find something to sell. Whatever they can sell in order to survive. I think the hardest thing is feeling that one is very vulnerable. I don’t like the word vulnerability, but well, it’s the only one I find at this moment. That one feels alone. Here there are many elderly people who are alone.

Inés: Here there are practically no nursing homes for the elderly. There aren’t any. The ones that exist aren’t enough for the elderly. Here there is no special support. Pensions are laughable, that is, pensions don’t cover anything. At this moment my pension went up to 1,625 pesos. A carton of eggs costs you 3,000 pesos. So, of course, those who are worse off are the retirees.

Eliezer: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Estudios. I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: And I’m Silvia Viñas.

Cuba is one of the most aged countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. A quarter of the population is over 60 years old. That figure is expected to increase, and by 2030, a third of Cubans on the island will be over 60 years old.

Eliezer: Between the lack of food and medicines and the exile of their relatives, many reach old age with the feeling that a promise has been broken. Today: what old age is like for the generation that gave their youth to the Cuban revolution.

It’s January 23, 2026.

Silvia: Our producer Mariana Zuñiga continues the story.

Mariana Zúñiga: When the Cuban Revolution began, Inés had just turned 11. She remembers that Fidel Castro’s rise to power generated hope for most of the people she knew.

Inés: I would have to tell you that in those first years, I didn’t really know what was going to happen, and I began to learn through my brother, who did get involved very quickly—in 1960 in the militias—I really, until university, I don’t think I was revolutionary or anything. The only thing that interested me was studying.

Mariana: Inés studied chemistry at the University of Havana, but they didn’t only study mathematics or the characteristics of the periodic table. They combined formal education with work in the fields. All of this in support of the revolutionary project. The idea that their generation had the responsibility to consolidate the revolution was something that was constantly reinforced at school.

Inés: Yes, that was like part of the curriculum. I mean, I entered in October, more or less, of ’66 and already in April we went there, to a province called Sancti Spíritus, to pick onions, etc. That was part of the curriculum. In that case it was 35 days. You had to go there. I mean, it didn’t occur to anyone to think that it was either mandatory or voluntary. It was something that was just part of it. And besides, all your classmates did it. So all of that excited a youth that wanted to move the country forward.

Mariana: To enter the Union of Young Communists, Inés had to lie. The first time she tried, they rejected her for believing in God and for having a sister in the United States. That made her stateless and a traitor.

Inés: I wanted to enter the Union of Young Communists. I admired my comrades who were in that, I admired them tremendously and I also felt that being in the communist youth, I could help the Revolution and the country more. And regarding my sister, it was true that I did stop writing to her. And that’s how I entered the Youth.

Mariana: Over time, Inés learned not to mention her sister anymore. Not to think about her. She says she still hasn’t been able to fully overcome how cowardly she was in giving up that relationship.

Inés: Of course, the years went by and I became quite disappointed, but it was very difficult to make the decision to say “I’m leaving the party.”

Mariana: Inés describes her disappointment as a slow process. Slow but continuous. Like a drop of water that pierces a stone little by little. For her, who was a teacher, her students were key to realizing that the model didn’t work as they had promised her.

Inés: They helped me a lot. My children, the students, my friends’ children, they were the ones who challenged me so that when I wanted to explain something to them, I realized that I had no arguments to refute what they were telling me. I realized that my arguments didn’t convince them.

Mariana: Just as it happened with Inés, many other people of her generation also became disappointed with the project. Her brother, for example, who was a lieutenant colonel, when he retired he received no help from the regime. Nor a decoration or congratulations for all his years of service. Inés says his old age was very sad. He was very sick and in his last moments, neither his colleagues nor the institutions he worked for gave him a hand. He died forgotten. Both by his wife, who left him alone when she migrated to the United States, and by the revolution, to which he dedicated all his energy and sacrifice.

Inés: Here there’s nothing… Nothing, nothing, nothing in favor of older people, of the elderly, nothing. I can tell you, Mariana, there isn’t.

Mariana: Inés has spent years reflecting on this topic and has asked herself a lot of questions: whether her generation was naive, whether it was cowardly, whether they were convinced or manipulated, whether they are guilty or victims.

Inés: I do feel guilt. Not a guilt that gnaws at my conscience, no. It’s a guilt that I understand. It’s a guilt of not having woken up in time. It’s a guilt of having been perhaps naive, of having been too innocent, too… But I can’t erase that. But then I realized over time that if I hadn’t woken up at that time, now that I was awake, I should leave my testimony. I have written several things related to my personal testimonies, to the things I saw and I will continue doing it, I will continue doing it as long as I can.

Mariana: Inspired by her experience and that of others, Inés wrote a story and sent it to the platform *Cuido60,* a project that seeks to disseminate information about aging in Cuba. That’s how I learned her story.

Inés: I sent them my experience, very brief, who I was, etc. And well, what I thought about the disillusionment that one suffered throughout these years, right?

Mariana: The story is titled: “The Old Age We Never Expected.” It won a contest and is now part of a book about old age in Cuba.

Inés: Of course, it was a paradise that they sold us. We weren’t thinking about being millionaires. We thought it should be a country with everyone and for the good of all, which is what they told us. I mean, I didn’t dream of being a person who traveled the world or anything like that, but of having a peaceful old age, in a place where I had the bare minimum. You understand? That’s what I dreamed of. Of course we don’t have it. Nobody has it. It’s not that we don’t have it, nobody here in this country has it. I never expected this old age.

Mariana: When I was in Havana, I visited an institution run by the Catholic Church in the city center, in an old building. Different social projects operate there. I went to learn about *Otoño*, an initiative that seeks to improve the quality of life of older adults in the city. They offer classes, talks, and once a month they throw a big birthday party. That day they were celebrating everyone who had birthdays between December and January. I arrived just in time to sing “Felicidades,” the traditional birthday song in Cuba.

Chorus: One, two, three! *Happy birthday friend on your day, may you spend it with healthy joy, many years of peace and harmony. Happiness, Happiness, Happiness.*

Coordinator: Start sitting down little by little. So now…

Mariana: After singing, everyone sat in a circle and the coordinator invited the birthday celebrants to stand up one by one, introduce themselves and tell something about themselves.

Nancy: Nancy de los Ángeles, I was born on January 27, 1953. I’m 72 years old and I like it when they sing “Felicidades” to me.

Coordinator: Another birthday person?

Mariana: About eight people stood up to speak. All women. And almost last, shyly, Laura stood up, a lady who has been visiting the center recently.

Laura: My name is Laura, I was born on December fourth.

Mariana: It’s not very clear from the audio quality, but Laura says she’s trying to socialize because she doesn’t know many people. So, making friends is her main motivation for coming to the center.

Mariana: When the party ended, I looked for her to talk.

Laura: My name is Laura González Otero. I’m 74 years old.

Mariana: She studied geography at the University of Havana and worked at the Academy of Sciences all her life.

Laura: I’m a researcher. I did candidacies, doctorates, those kinds of things. All of that has passed and now I’m retired at home.

Mariana: And do you have children? Did you have children?

Laura: I had a son who died. I don’t have family here in Cuba. I don’t have any family in Cuba.

Mariana: Unlike most Cubans who today are living the consequences of a long economic crisis, Laura says she doesn’t have money problems.

Laura: Because I have some wonderful nephews and nieces who support me on their own.

Mariana: They send her money from outside. Really, one problem is another.

Laura: What happens to me is that I don’t have a support network.

Mariana: Laura lives alone in an apartment. In recent years, she has had periods when she has felt really alone. Her husband passed away, and as the situation worsened her loved ones left the island: her neighbors, her friends and the rest of her family. One by one.

Laura: My niece gets married and goes to England. My nephew gets married and goes to Bilbao. My brother and my sister-in-law left. I mean, my people started to leave. My friend, that lifelong friend, since we were young, we studied together at the Alliance before entering university. That friend left me. Then another one that I was her tutor too. I mean, when you come to see I don’t have anyone from more than three years ago that I know here.

Mariana: I once read that Cuba is the country of the infinite goodbye, where people are born, grow up and migrate. And although migration is not a new phenomenon for Cubans, experts say that Cuba is experiencing a massive exodus. The largest in its history. Since 2021, many more people began to leave the country for different reasons: the collapse of the economy, scarcity, the health crisis, constant blackouts, the fall of the tourism sector and political repression. All these factors have emptied the country. For years, Cuba’s population was around 11 million people. Today, a little more than eight million live on the island. That is, in just four years, the Cuban population fell by 24%. The migration crisis profoundly affects the lives of older people, like Laura. Parents, uncles and grandparents who are left alone in Cuba.

Laura: Because there’s a generation that’s missing, which is my nephews’ generation. People in their 30s and 40s. Those people are not in Cuba, and neither are their children. You realize? People are missing.

Silvia: We’re taking a break, and when we come back: how Cubans like Laura who have stayed on the island without a support network face old age. We’ll be right back.

Eliezer: We’re back. In Cuba, most older adults live alone, especially women. Like Laura, there are thousands throughout the country, but most are in Havana, one of the most aged places on the island. Mariana continues the story.

Mariana: Loneliness has put Laura in very complex situations, especially with her health. She remembers the time she had to have cataract surgery. It just coincided with the beginning of the pandemic.

Laura: The day they closed was Saturday, I was being admitted on Tuesday to have eye surgery. It was the cataract, you know, planned and I spent the pandemic blind in my house. That was terrible.

Mariana: In three years she had surgery five times. Three on the right eye, but only two on the left.

Laura: That’s why I have this one droopy, because I didn’t want to do the third one. And then, this thing with my heart happened.

Mariana: In 2024, Laura began to feel bad. When she went to the doctor, they told her that her heart was failing again. She had already had a heart attack a few years ago. The doctor suggested putting in a pacemaker. And although her nephews sent her the expensive device from Spain, it was like a déjà vu. She would have to go through the entire post-operative process alone again. But this time she was luckier. Two days before the surgery, a new neighbor offered to help her.

Laura: She accompanied me on the day of the surgery. She brought me clothes, she brought me food, those things. And then, when I left the hospital, she helped me. She stopped working those days and I had to give her money to live. But she behaved very elegantly with me and was very good.

Mariana: After recovering, she decided that something in her life had to change.

Laura: I’m trying to find something that cheers me up…

Mariana: That gets her out of the house, out of the silence. That takes her to hear the noise of the street, to meet people. And that’s how she found the *Otoño* project, the cultural and educational space for older adults in Havana where I met her.

Laura: And I came here because I realized that I was totally isolated. So I started taking a course in positive psychology and then I started there. Then I entered one on mobile telephony. And so I come and socialize. I have friendships there.

Mariana: And now that you’re coming and meeting people. How do you feel? Do you feel it has helped you in any way?

Laura: Of course! I have relationships, at least I interact with people. People who have my story. Because I have, for example, neighbors. But my neighbors’ stories aren’t mine. Everyone has their lives, their things, neighbors are the closest family for certain things, but they’re not people with whom you have affinity. So, when you see an old woman who has the same stories as you, your same history, who was in the same… I mean, it’s something else.

Mariana: In this center, Laura has found companionship and attention. Care that, otherwise, she wouldn’t have received because the care system that the regime offers is inefficient, it’s broken. Let’s remember that Cuba has one of the most aged populations in Latin America, and it’s expected that by 2050, Cuba will be the ninth oldest country in the world. This is a problem and the state knows it.

Archive audio, presenter: Attention to demographic dynamics is a priority for the Cuban government.

Archive audio, journalist: Therefore, they have priority, equally, fertility programs and the maternal and child program.

Mariana: These programs aim to stimulate birth rates, whether by offering greater care to pregnant women and newborns, or by supporting families that have more than two children. The Demographic Studies Center of the University of Havana also believes that the only option to deal with the increase in old age is for more people to be born on the island. But this solution is very difficult to achieve. The figures show that the number of people under 15 has dropped. More deaths than births are reported on the island. And Cuba’s fertility rate is the lowest in the region. It’s that here, women of reproductive age are the ones who migrate the most. And many of those who stay simply don’t want to have children. At least not in this context, as a mother explained to a local journalist.

Archive audio, Cuban woman: Today there wasn’t even bread for the boy to go to school. How do you think one is going to keep giving birth? You can’t give birth.

Mariana: Furthermore, the problem with these birth rate policies is that they don’t solve the main problem: the lack of attention and care for the elderly. There aren’t enough nursing homes, nor state programs, nor an exclusive union to serve retirees. So, the situation on the island makes aging even more complicated than in other countries.

Laura: Cubans live a long time, because there was a time when public health was good and it was a political banner. I mean, there was a lot of vaccination, a lot of medical care. Now there isn’t. Now everything is complicated. Now it’s like it doesn’t work. There are no medicines. I need six medicines every day. None are available at the pharmacy. I have a card that says they have to give me that medicine at the pharmacy and for three months none of the medicines have come.

Mariana: It’s also not easy to find supplies like needles or reagents to do simple clinical tests. This, many times, prevents the elderly from getting a timely diagnosis. Scarcity has become a chronic problem. More than 70% of essential medicines are not available in pharmacies. To get them, you have to go to the informal market or to social networks, where medicines are bought, sold or exchanged. Of course, at super high prices.

Laura: So I bought it. Why? Because I have money that my nephews send me. Both couples support me. They each do it as if it were a competition. Let’s see who sends me more things and who sends more, who helps more. It’s a very nice thing, but it hurts me a lot, because I worked all my life. All my life I worked. Now I’m retired and I earn 1,528 pesos in pension. With 1,528 pesos you can’t do anything.

Mariana: That’s more or less four dollars. And every day the value of her pension goes down because of inflation. When I met her, that amount was only enough to buy about three kilos of rice and less than a kilo of tomatoes. In July there was an increase in pensions and retirement benefits, but it really still doesn’t cover basic needs.

Laura: And I tell you, I’m a super privileged old woman.

Mariana: Laura is very aware of her privileges. She knows that retirees who don’t have financial support from their family have a very hard time in Cuba. Here, older people are the most vulnerable and the most affected by the economic crisis.

Laura: I mean, you’re hitting rock bottom, but they always lower the bottom more. That’s very hard. So you also live in a surrealism and in a schizophrenia, because you hear the TV telling you that everything is fine, that everything is wonderful and that we are, wow! So you hear one thing and you’re living another.

Mariana: Laura’s nephews have offered several times to help her leave Cuba. Take her to live with them. She has refused. She doesn’t want to feel like a burden. Besides, she doesn’t have the strength to make such a trip either. She says she’s already very tired. Despite everything, for Laura nothing is eternal. She feels that the situation will change someday, but she also knows that neither she nor her generation will see it.

Laura: Regimes change, slavery ended, the Middle Ages ended. All of that ended. But the problem is that you only have one life. You’re not in a history book, because this story is going to be, 200 years from now: “in the year 59 a liberating revolution triumphed, I don’t know what. Then it went to communism, then it reached misery and in such a year democracy returned.” They’re three paragraphs in Cuba’s history, but it’s my entire life. I was eight years old when the Revolution triumphed and I’m 74. My entire life is stuck in a paragraph of Cuba’s history.

Mariana: When you were younger, how did you imagine your future would be and how different is that from what you imagined?

Laura: For me, the future was going to be good. That I was going to have a good profession, I was going to have a professional life, that I was going to be happy. I was going to enjoy the countryside. I was going to go to good beaches. That I could go hiking in the mountains. All of this is normal that we didn’t do. Well, none of that happened. My future was a disaster.

Mariana: The case of Laura tells us about another phenomenon of old age in Cuba: the care crisis. Most of those who care for older adults are women, specifically daughters. And although many of these caregivers are already over 60, they would still be expected to care for the elderly people in their family.

Rosario Rodríguez also grew up with the idea that there would be food for everyone. She is 60 years old and lives in San Miguel del Padrón. It’s a low-income area in the southeast of Havana.

Rosario: We’re kind of from the countryside, in a certain way. We escaped a bit from the Havana vibe.

Mariana: Rosario has three children, four grandchildren, and works cleaning houses. She lives with her two older children and her granddaughters. When I visited her house, one of her granddaughters came running to greet us. She was wearing a very bright sky-blue chiffon dress.

Rosario: My granddaughter. My granddaughter.

Mariana: She tells me she’s happy because Saturday was Mother’s Day. I asked her how they spent the day. What they had done to celebrate with the little ones.

Rosario: No, no… My daughter made chicken and food like that but I’m not up for that. So I don’t feel like celebrating anything. No, nothing anymore, I lost everything.

Mariana: On Saturday, when Mother’s Day arrived, the girls’ father died. Pablito. Pablito was 47 years old and died of heart disease. Rosario says it was very sudden, totally unexpected.

Rosario: She had been a widow for three years. Her ex had also died of heart disease, at 50. Over time she had found the love of her life: Pablito.

Rosario: Saturday marked two years of being together. And he died.

Mariana: How sad.

Rosario: A tremendous sadness. Tremendous. I was taking care of him. I spent four days with him.

Mariana: Pablito died one early morning, and she was alone taking care of him and didn’t know what to do. She told me that first she called a neighbor and then the police.

Rosario: Alone. Me alone, alone with no one. No children, nothing. And they didn’t even manage to see him alive. My children arrived and I had the body here, already, and they arrived. But no one saw him alive. It was a very, very tremendous death. Very tremendous. I’m still, look, trying to process that they’re not here.

Mariana: We sat for a while and she told me that sometimes she had to stop thinking about Pablito to be able to move forward.

Rosario: I have to live here, you know. I can’t keep going on like this, because I would get sick, but the suffering is tremendous.

Mariana: Rosario says that at some point she’ll leave her house, because inside it’s still full of memories. And she believes that leaving can help her process Pablito’s death.

Rosario: This doesn’t help me being here, but well, I can’t be selfish or leave the girls.

Mariana: Her priority is her granddaughters. Pablito also had a 12-year-old son, but his mother is in Spain. Here in Cuba there are no relatives of his left. After his wake and burial, Rosario had no choice but to take charge of him. The boy is now officially a minor under state guardianship and Rosario doesn’t know how long he’s going to stay living with her.

Rosario: Imagine, we don’t even have a place to sleep. I have him with my grandson, on a mattress that’s falling apart.

Mariana: With Pablito’s son, there are two adults, two young people and four children. They all live crammed in a house where the kitchen is at the entrance. They don’t have a living room, and in total there are only two rooms.

Rosario: And now I have the responsibility that he goes to school, that he eats here. And well, because he doesn’t want to go to Spain. And it hurts me a lot that, oh my goodness, having another child that I have nothing to give him. It’s very hard, very hard.

Mariana: Rosario is in her sixties. It’s the time of her life when she should have fewer obligations. But the reality is that every day she has more. Not only did she lose the love of her life, but she has to take care of another child, even without having legal authorization. They’ll only give her that if it’s proven that the child’s mother won’t come for him to take him with her. Which remains to be seen.

Mariana: Despite everything that’s happening, Rosario keeps working. She has three or four houses that she cleans a couple of times a week.

Rosario: I have to work for the children, I have to work, because if not, I’m left with the children here and I have to pay for electricity, I have to feed everyone.

Mariana: Like Inés, her pension doesn’t cover anything. Besides, if she doesn’t work, she has no way to support her family.

Rosario: It’s like one thousand five hundred pesos. The thousand five hundred. It’s nothing.

Mariana: The one thousand five hundred pesos would be about twelve dollars a month, at the exchange rate. According to United Nations data, currently in Cuba 21 percent of the population lives in poverty, that is with less than two dollars a day. And as we said before, Rosario lives in a low-income area of Havana. She would consider herself working class, although she says that class thing doesn’t exist anymore there, because nowadays, she says, only the poor and the rich exist.

Rosario: In Cuba there are poor people like us who have absolutely nothing. And there are people who have tremendous cars. What is that? Where? How? From what? And I have nothing. And I’ve worked all my life.

Mariana: Rosario has been working for more than 40 years. She has been a book seller, an inspector in the education sector, a tour guide.

Mariana: Nowadays, the only way to support herself and her family is with the remittances that her youngest son abroad sometimes sends her. And with what she earns cleaning houses.

Mariana: Rosario is also very sick. She suffers from diabetes and high blood pressure. She needs medicines, like insulin, which are almost impossible to get in Cuba, only by importation and they cost a lot. So she depends entirely on what her son from abroad sends her. And she says she tries to take care of herself as best as possible amid so many responsibilities.

Rosario: I don’t know. I’ve had certain moments when I’ve really felt bad, and I say, well, I can’t get sick or die, but I’m very discouraged about that. The first day they gave me such anxiety that I almost died of a heart attack. I don’t have anything to pay for my health, everything I have my son sends me, in pills.

Mariana: And there’s Rosario then. She says she’s more or less healthy, but very stressed. She tries to keep her blood sugar levels stable, but it’s difficult. She has to juggle taking care of her health, caring for five children, working every day and now also processing grief from a very sudden death. All without much support or accompaniment from anyone.

Mariana: So, what would you like to exist?

Rosario: Oh, a quiet life. Not asking anyone for anything. That I can support myself. And that my grandchildren can also move forward. To age peacefully and watch my grandchildren grow and for them to have a future.

Mariana: Perhaps that’s one of the great burdens of aging in Cuba, not only having to worry about your basic needs, but about those of your entire family. We come back to the fact that in Cuba there is no real support system. Because the one that exists works poorly. It’s insufficient. And in terms of long-term care for elderly people who need someone to care for them, it’s also inconsistent. In fact, according to a study on Aging and Disability in Cuba, published by the NGO HelpAge International in 2019, two out of three older adults with functional dependence do not receive any type of formal care. And it’s their relatives, friends and neighbors who have to take care of them.

Mariana: Laura, the lady we met at the beginning of the episode, knows very well what this is like. Not only does she care for her 97-year-old mother, but also for her husband who is 91. They don’t have any kind of external help. But she at least can lean on her two children, who help her. At least remotely, because both live outside Cuba. They send her money from time to time. Even so, when there are blackouts that can last more than 12 hours, it’s very difficult to keep medicines in good condition.

Laura: It’s just that when the power goes out, I have to put everything in water with ice. Everything that needs refrigeration. It’s something very complicated with them and enormously draining. So I feel very alone, very alone. Sometimes well, what do I know, I sit and cry for a while, and I talk to my children on the phone. Well, I try not to cry with them, but sometimes the tears come out, as I say. I cry a lot, a lot, a lot.

Mariana: Laura’s story also represents another important theme in this episode, which we can’t lose sight of: exile. It’s not that she’s alone just because. It’s not that Rosario survives on so little just because. No. It’s that their support networks, their relatives, their children, aren’t there anymore because they all migrated and left Cuba.

Mariana: Cubans of all ages continue to leave the island. In 2022 alone, more than 300,000 left Cuba, and there are enormous lines for appointments at consulates in Spain, the United States and Mexico. That means that those who stay are frequently the elderly. Those of more advanced ages, those who find it difficult to migrate or who cannot do so for health or economic reasons.

Mariana: Irina Tejera spoke with us about her experience as a caregiver for her uncle. She is 62 years old. Unlike Laura, she doesn’t live with her uncle, but since his wife died of cancer last year, Irina goes to his house almost every day. Her uncle is 90 years old, his eyesight and hearing aren’t good, he walks with a walker. Although Irina has three siblings, they all live outside Cuba: one sister in Europe and two brothers in the United States.

Mariana: Irina says yes, they contribute some money, but clearly it’s not enough. Especially because now she doesn’t have time to work and generate income independently.

Irina: He has four children. They all live outside, almost all. He has a daughter here who doesn’t appear even by mistake. Because when you see them like that, I love you, I love you and from afar nice, nice, nice, but in reality it’s not like that. There I am with him, but I’m going through hardship, a very strong hardship. Because if I don’t ask my siblings here, no one sends anything anymore, they forgot.

Mariana: But Irina says that when she lost her husband a few years ago, her uncle was always there. He was like a father. Now he needs her. She says she used to sell crafts, but now she can’t, because she’s with her uncle all the time.

Irina: I have it etched here. If I don’t take care of him, I don’t know who will. I don’t want the old man to die. And now what I’m doing is working. I made some pendants. What I know how to do is crafts. So that’s what I’m trying now to give to some friends, to sell for me.

Mariana: Irina used to sell her crafts at Paseo del Prado, near the city center. But now there’s no way to accommodate her work with caring for her uncle, which takes up practically all day.

Irina: I wake him up at eight in the morning. While he has breakfast, he washes himself alone, he spends half an hour with the walker going back and forth and then with the cane. I finish with him every day at eleven in the morning. At that time I have to start doing things, things that take me longer because I’m not a good housewife, and since I don’t have money, well, I have to start working here at home. So with him it’s very difficult because give me the bedpan, do this thing. He urinates alone, but he still wets everything because his hands tremble. So you clean rags, wash and you have to be constantly on top of him. Even when I see him very serious I have to leave what I’m doing and sit with him, and that affects you a lot.

Mariana: Irina says she’s mentally overloaded, that she’s lost almost 20 kilos.

Irina: I have something here in my eye, like this, that makes my upper eyelid tremble for a week. It goes away, it comes back. I’ve noticed that I come here and I don’t know what I’m going to look for, I don’t know what I’m going to do. And I’ve seen things in me that I say, well, I’m screwed. I’ve had moments here when I’ve woken up at dawn short of breath, short of breath where you can’t breathe and that’s nothing other than this whole process, which is very hard and very draining.

Mariana: Being a caregiver has a very profound impact on people. Irina suffers from what’s known as caregiver syndrome, a state of physical, mental and emotional exhaustion that develops in those who care for someone continuously. She stopped worrying about herself a long time ago. She hardly leaves the house. She doesn’t even go to the doctor, even though she suffers from blood pressure and thyroid. Remember she’s 62 years old. She herself is aging.

Irina: Aging is very screwed up for me in general. I had a great aunt from the countryside, she died at about 90, who said that the ugliest thing in the world is old age and misery. Of course we care about having this wrinkle, this wrinkle. You start to see them. Ah, you say I’m more interesting, I don’t know what, perfect, but it’s still annoying. What happens? That there you have alternatives of a cream or a gym and the lifestyle and diet, of course, but in Cuba it’s terrible, in Cuba, as I told a friend the other day, that all I need is a mustache to be called Roberto.

Irina: You finish bathing and you don’t have cologne, perfume, earrings, anything that makes you feel good about yourself and that you like. You don’t have it. Aging in Cuba is very, very screwed up. Besides, the diet. I like to eat protein and vegetables. I don’t like rice. But well, I have to eat rice like I was Chinese, because there’s nothing else.

Mariana: Do you find a good part? Do you find something positive?

Irina: Well, I should tell you yes, but no, I don’t find it. Let’s see, I’m grateful every day to breathe and be alive and reasonably sane, right? That my uncle is stable. Because besides that, I don’t have money to take him to his medical appointments. He stopped going. I try to feed him well. I check his blood pressure, his parameters. And so far I want him like this. Not a bone hurts him. It hurts me more than him. Grateful to be alive and because I know there are many beautiful things that one can enjoy.

Mariana: During my visit to Cuba I met many elderly people, and it would be unfair to say that everyone has the same experience aging. Some, those who can—those who aren’t so alone, or so poor, or caring for someone—look for ways to give meaning to their days. To, as Irina says, find beautiful things they can enjoy. I was invited to an acting class for older adults at the social center where I met Laura, the lady who lost her support network because her family and loved ones left Cuba. The class is led by Enrique, a retired Argentine journalist who has lived in Cuba for more than a decade.

Professor Enrique: Well, comrades, let’s begin. Let’s begin because we have quite limited time.

Mariana: There I found a group of ladies who made theater their refuge.

I saw them doing breathing exercises.

Professor Enrique: And we’re going to start with the inspiration with the mouth half-closed.

Mariana: They also improvised.

Professor Enrique: The theme will be: here we are, this is who we are.

Student: Oh my goodness, I who left early to solve this problem. I get to where they’re printing and there’s no power.

Mariana: And they sang.

Professor Enrique: Music.

Student: *If you think of coming back to me and conquering me again…*

Mariana: At the end of the class, I sat down to talk with some of the students. I wanted to know what theater meant to them at this moment in their lives and what motivated them to keep coming.

Rosario: Rosario de la Caridad Rodríguez Pérez. 70 and… One forgets, 74 years old. Look, my happiness is so great, because it’s not that we feel fulfilled because we’re acting and we hear the audience’s applause. That’s wonderful. But the most wonderful thing is that we’re being requested. We’re going to perform at a school for special needs children. We’re going to act for them. They request us from a cultural center, so I feel useful and I feel that I give happiness to others and they don’t know that I’m giving it to myself too. It’s wonderful.

Juliana: My name is Juliana Díaz Ramírez, I’m 74 years old. That energy of feeling useful, of being able to make others laugh as we do in theater, well that strengthens us, gives us life, makes us happy.

Xiomara López: My name is Xiomara López Padilla, I’m a founder of the group. We’ve learned a lot. I never thought that after having studied, because sometimes one says no, because I know everything, no, in life you don’t know everything. I’ve learned things that they’ve taught me here and from the same colleagues I’ve met. We get together, we sing, we dance and I believe this is a beautiful project and many people have retired and found another life here.

Mariana: This episode was produced and reported by me, Mariana Zúñiga, with support from Eileen Sosin. It was edited by Silvia, Eliezer and Daniel Alarcón. Bruno Scelza did fact-checking. Sound design is by Elías González, with music composed by him and Remy Lozano.

We want to thank Elaine Acosta, Pablo Argüelles and FLIP, the Foundation for Press Freedom, for their support on this episode.

The rest of the El hilo team includes Daniela Cruzat, Jesus Delgadillo, Samantha Proaño, Franklin Villavicencio, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask you to join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to go deeper into today’s episode, subscribe to our email newsletter by going to elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it every Friday.

You can also follow us on our social networks. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook and Threads. You can find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share the episodes.

Thanks for listening.