Amazonía

Ecuador

COP30

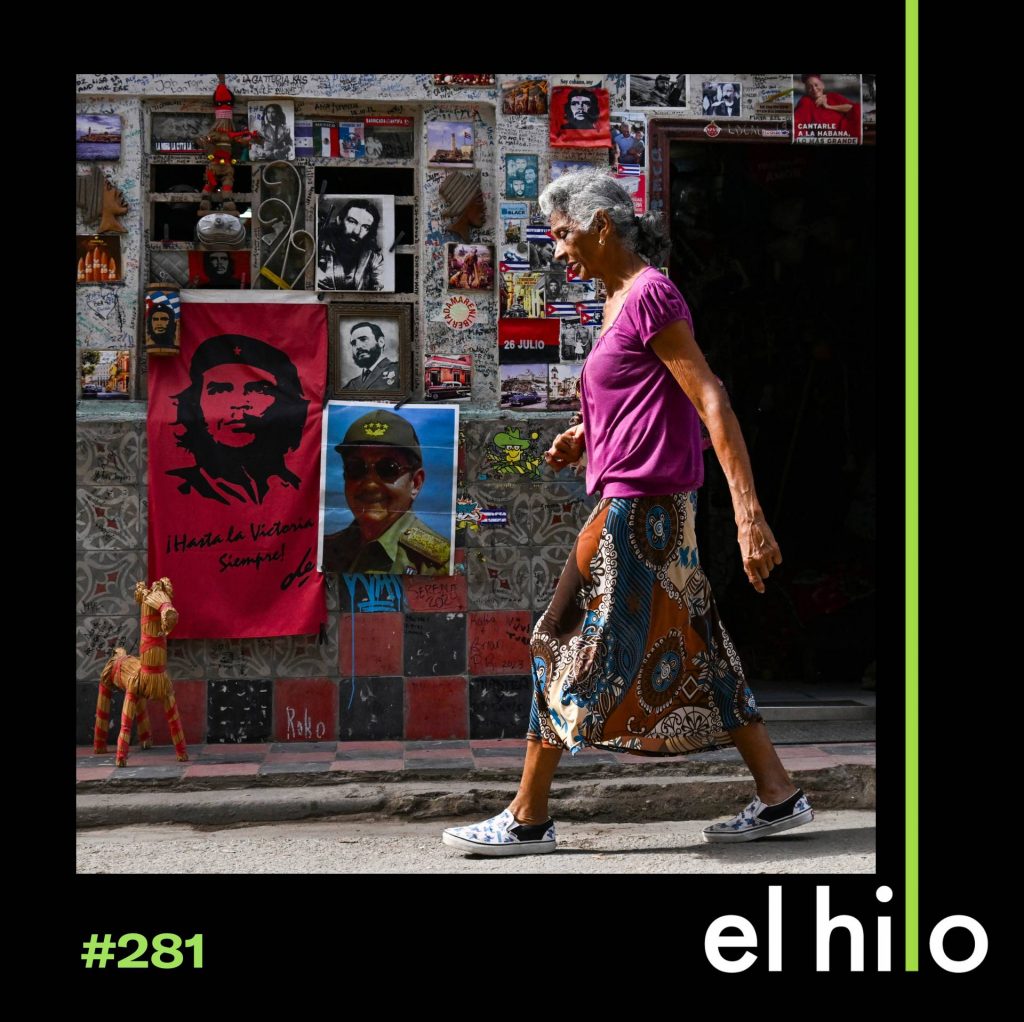

Guerreras por la Amazonía

Toxic tour

Chevron-Texaco

Shushufindi

Lago Agrio

UDAPT

Esta serie fue producida con el apoyo de Movilizatorio y Alianza Potencia Energética Latam.

A pesar de las amenazas, la contaminación y el desequilibrio de poder, las jóvenes de Guerreras por la Amazonía y otros activistas siguen luchando para defender sus territorios de los abusos de la industria petrolera. En este episodio acompañamos al periodista Joseph Zárate en un “tour tóxico” para entender la magnitud del desastre que causó Chevron-Texaco en la amazonía ecuatoriana y cómo la impunidad y la negligencia siguen afectando a las comunidades. Terminamos el recorrido en el Yasuní, un recordatorio de lo que está en juego si no se cumple con la voluntad de los ecuatorianos de terminar con la explotación petrolera en el área protegida más grande del Ecuador.

Créditos:

-

Reportería

Joseph Zárate -

Producción

Silvia Viñas -

Edición

Daniel Alarcón -

Investigación

Rosa Chávez Yacila -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción digital

Natalia Sánchez Loayza, Helena Sarda, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Remy Lozano -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

Ilustración

Maira Reina

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Esta serie fue producida con el apoyo de Movilizatorio y Alianza Potencia Energética Latam

Wilmer Lucitante: Para ellos somos una piedra en el zapato nosotros, porque hacemos este tipo de trabajo que es como evidenciar las malas prácticas que ellos desarrollan, o sea la irresponsabilidad de ellos.

Eliezer Budasoff: El que habla es Wilmer Lucitante, un monitor kofán de la Unión de Afectados y Afectadas por las Operaciones Petroleras de Texaco (UDAPT). Es una organización que reúne a decenas de comunidades que han sido perjudicadas por la industria petrolera en la amazonía ecuatoriana.

Wilmer: Para las empresas petroleras somos una piedra en el zapato porque decimos la verdad (sobre) la contaminación. Exigimos nuestros derechos.

Joseph: Él tiene 34 años, es padre de dos niños. Y él vive, de hecho, vive cerca a un mechero, a una de esas construcciones que liberan gases tóxicos.

Silvia: El periodista Joseph Zárate, nuestro guía por este recorrido por la Amazonía, se juntó con Wilmer en Lago Agrio, una ciudad en la provincia de Sucumbíos. Está al norte de la Amazonía ecuatoriana, muy cerca de la frontera con Colombia.

Joseph: Es un lugar muy, muy particular, porque antiguamente fue el territorio ancestral de varios grupos originarios, pero en particular de los kofanes, que fue, sobre todo desde mediados del siglo 20, fue siendo desplazado por las industrias del petróleo. Entonces yo llegué hasta ahí porque de ese lugar son las Guerreras por la Amazonía.

Eliezer: El grupo de niñas y adolescentes que hacen activismo para defender sus territorios de la contaminación petrolera. Conocimos a una de ellas, a Leonela, en el episodio anterior. Son las chicas que ganaron una demanda para que eliminen los mecheros que quedan cerca de sus casas.

Joseph: Entonces yo quería conocer un poquito más sobre la realidad, y sobre el lugar donde ellas viven, pero sobre todo entender por qué ellas estaban luchando, ¿no? En su activismo.

Wilmer: El tema es que no se han eliminado hasta ahora. En la sentencia dice clarito de que deben eliminar los mecheros que están cerca de las poblaciones. Y no lo han hecho.

Joseph: Y él me explicaba de que estaba construyendo su casa, y me mostró el lugar donde estaba construyendo su casa, y me di cuenta que cerca, a unos metros de su casa, ya no había un mechero nomás, había dos más. O sea, habían aumentado los mecheros. Y yo le pregunté ¿Oye, pero por qué estás construyendo tu casa aquí? O sea, ¿por qué no te vas? Si yo fuera tú, me iría.

Joseph: Quería preguntarte. ¿Qué te hace sentir eso? Como un padre de familia, que tus hijos estén cerca del mechero.

Wilmer: Al comienzo pensaba ir a otro lugar, ¿no? y alejarme del lugar donde haya contaminación. Pero me puse a pensar, mismo… Es como huir, ¿no? es abandonar. ¿Cómo vamos a dejar que hagan lo que se les da la gana?Porque no podemos permitir que pase cinco años más, 10 años más, 50 años más con este tipo de contaminación.

Silvia: Esto es Amazonas adentro, una serie de El hilo, de Radio Ambulante Studios. Episodio 2: El Chernóbil de la amazonía.

Joseph: Uno de los objetivos que yo tenía en Lago Agrio era poder hacer un recorrido por el desastre, ¿no? Hay un recorrido que se llama el Toxic Tour, el tour tóxico, que hace, digamos, la UDAPT, esta asociación que defiende a los afectados por los derrames de petróleo de Texaco en esa zona, para de alguna manera generar conciencia ¿no?, sobre el efecto terrible que tiene esta industria petrolera en esa zona del Ecuador.

Donald Moncayo: Es una manera de cómo puedo llegar hacia la gente ¿no? Nosotros no tenemos los medios tan grandes, tan fuertes cómo poder llegar. Y sobre todo, no es lo mismo que estar viendo ahí, oliendo ahí, viendo cómo la naturaleza también hace su parte de querer limpiar, de querer remediar lo que nosotros los humanos hemos destruido, ¿no? A mí me interesa que la gente venga, que conozca, que sepa.

Joseph: Donald Moncayo es un activista medioambiental. Es un agricultor. Él se ha dedicado a liderar y a coordinar la UDAPT. Entonces es un hombre muy valiente. Un hombre que ha, digamos, arriesgado muchas cosas en nombre de de su lucha. Él tiene una hija que la hemos escuchado, que se llama Leonela.

Joseph: Tú naciste aquí.

Donald: Sí. Yo nací un 20 de noviembre de 1973, a 200 metros del segundo pozo que perforó Texaco acá, Chevron acá. Entonces yo vi todo. He visto todo esto. A mí no, no me lo contaron. Yo lo viví.

Joseph: De hecho, su madre murió de cáncer. En realidad para él, el defender esta causa por lograr una reparación a los afectados no es algo meramente, o propio del trabajo de un activista, nada más. Para él es algo personal. Y es muy parecido a la historia que me contó Diego Robles, que también perdió a su madre. Y es muy parecido también a lo que me contaban los niños del Tena, los Yaku Churi, porque también, de alguna manera, veían afectado el lugar donde ellos han aprendido a nadar, donde sus padres van a lavar la ropa, a tomar el agua del río, a cocinar. Entonces, cuando tú conversas con estas personas como Donald, tú ves en en su manera de ser, en su manera de hablar, que este no es un trabajo simplemente como de personas que quieren cuidar el medio ambiente, o que quieren proteger la vida de los árboles, o de los animales, o de los ríos. No se trata solamente de eso. Hay algo personal que los atraviesa profundamente. Algo que ha fracturado, algo muy hondo de sus vidas, de su identidad, de sus afectos. Y en esa fractura es donde surge este impulso, este fuego de querer levantar la voz, de querer hacer algo al respecto.

Donald: Ir a hacer esos Toxic Tour es eso, ¿no? Ir realmente a contar realmente lo que pasó y justamente despertarles a los jóvenes que una alternativa no es realmente las empresas transnacionales. Yo dudo mucho de que una empresa transnacional entre a tu país, entre a tu pueblo, entre a tu comunidad a dejarte beneficios.

Eliezer: Joseph, hablemos un poco del Toxic Tour. Pero antes de que nos cuentes cómo fue ese recorrido, nos gustaría entender más sobre qué pasó en esta zona y por qué hacen este tour.

Joseph: Este lugar es el escenario en Ecuador que los expertos han llamado como el peor desastre petrolero del mundo. Le han llamado incluso como el “Chérnobil de la Amazonía”, debido a la desastrosa contaminación dejada por esta transnacional, por Texaco, que ahora se llama Chevron. Entonces, durante casi 30 años, desde los años 60 hasta 1990, Texaco-Chevron derramó más de 16 mil millones de galones de desechos tóxicos en el norte de la Amazonía de Ecuador, esa zona que les mencionaba, que es Lago Agrio. Entonces, estos tóxicos han dejado residuos peligrosos en cientos de pozos abiertos que fueron excavados en el suelo del bosque, ¿no? En el mismo suelo del bosque. La población local sufre cáncer, sufre defectos, a veces los niños, por nacimiento. Una serie de problemas de salud que hasta el día de hoy el Estado ecuatoriano no ha podido ayudar a resolver. Entonces, en el 1993 se inicia una demanda colectiva contra Texaco en Nueva York. Y esta demanda, digamos, liderada por la UDAPT, estaba representando a unos 30.000 habitantes de esa zona del Ecuador que han sido afectados por las actividades de extracción petrolera en Lago Agrio. Pero fue recién ya en el año 2011, o sea, pasaron muchos, muchos años después para que la Corte Provincial, recién en Sucumbíos, en Ecuador, dictara una sentencia contra Chevron por los daños, por la negligencia extrema con la que operó esta empresa a cambio de las ganancias que esperaba recibir. Esta sentencia también ordenó que la empresa pagara 9.5 mil millones de dólares en costos para reparar los daños por todo lo que hizo esta explotación petrolera.

Donald: El caso Chevron consiste en que deben de pagar, en que deben de hacer realmente una remediación, una limpieza apta para que se pueda vivir con dignidad, que eso es lo que buscamos con esto. Ya que lo que vinieron a hacer es a destruir realmente nuestra casa común, donde vivimos nosotros.

Joseph: Pero hasta el día de hoy, pues no se ha pagado ni un solo dólar.

En el 2013, por ejemplo, la Corte de Justicia de Ecuador ratificó la condena. En el 2018 volvió a ratificar la sentencia, y que se tiene que pagar. Pero hasta ahora no se ha pagado, o sea, ni se ha limpiado el desastre, los desechos siguen contaminando esa zona de la Amazonía ecuatoriana. Entonces, no se ha reparado nada. De hecho, según esta organización Amazon Watch, hasta el 2024, como 13 años después de la sentencia, Chevron habría obtenido más de 200 mil millones de dólares en ganancias. Y hasta ahora no ha pagado nada.

Donald: Y es por eso. O sea, nos lleva a seguir luchando, a seguir buscando realmente de que el culpable de todo esto que no se haga la víctima, sino que asuma realmente su responsabilidad, porque es una responsabilidad de ellos de dejar tal cual como encontraron antes de de ingresar a destruir todo.

Silvia: ¿Cómo empieza el tour tóxico? ¿Cómo los preparan para ir por este recorrido?

Joseph: Sí, bueno, en primer lugar, cuando uno quiere hacer el Toxic Tour, simplemente es ir a las oficinas de la UDAPT, ¿verdad? Que son unas oficinas muy modestas, donde siempre hay voluntarios, voluntarias. Siempre vas a encontrar a Donald. Hay una habitación entera con todos los folios de las demandas, que lo tienen ahí guardado. Y es impresionante, porque son una tras otra, folios de folios con pruebas, con los expedientes, los testimonios de la gente. Yo tuve la oportunidad de verlo y es muy impresionante, porque uno puede dimensionar ahí la cantidad de trabajo y de años de lucha. Y bueno, lo primero que uno tiene que recordar es que tienes que llevar botas, ¿no? Yo no llevé. Entonces… Porque, bueno, vas a pisar mucha agua y barro y cosas mezcladas con petróleo. Pero bueno, el Tour me acuerdo mucho que empezó con unas primeras palabras de Pablo Fajardo.

Pablo Fajardo: Cuando se contamina un río se afecta todo el entorno: los mamíferos, los peces, la cultura de los pueblos, el ambiente, el agua, todo directamente ahí

Joseph: Pablo es abogado y asesor jurídico la UDAPT, es un activista que tiene muchísimos años defendiendo esta esta causa. Y esa mañana en el bus, antes de partir, nos explicaba un poquito el contexto de lo que íbamos a ver esa mañana en el Toxic Tour.

Pablo: Tenemos 32 años de juicio contra Chevron. Le ganamos el juicio en todas las instancias del país. Hay cuatro sentencias condenatorias en contra de Chevron.

Joseph: Y él es un tipo muy, muy lúcido. Muy claro, muy frontal también. A veces, en su manera de hablar, creo que es incluso más frontal que Donald. Creo que es por su tono de voz. Donald tiene una voz un poco más suave. Pablo es muy directo.

Pablo: Así que bienvenidos por acá nuevamente, es un cortísimo resumen, hoy verán mucho más en el campo, pero invitarles también a… Ojalá, cuando vuelvan ustedes con más elementos también veamos cómo podemos ayudar en estas luchas. Primero, para que haya justicia. Segundo, para prevenir más daños de otras empresas, para denunciarlos también y que los gobiernos entiendan que la vida vale mucho más que el petróleo. ¿Sí? Muchísimas gracias y hermoso día. Disfrútenlo. Sí. Ahí van con Donald que es el jefe ya.

Donald: Que alce la mano el que falta.

Joseph: Y bueno, entonces estábamos en el bus, con un grupo de estudiantes de biología de la Universidad Central del Ecuador. Eran como una veintena de chicas muy jovencitas, que jamás habían visitado, muchas de ellas, la Amazonía, ni conocían de este problema.

Donald: Perforado en el año de 1969…

Joseph: Primero visitamos un antiguo pozo de petróleo que estaba como a una, no sé, media hora de la oficina de la UDAPT, donde desde mediados de los 60 hasta mediados de los 80 se extrajo petróleo. Ahora ya no hay más petróleo en ese lugar, sino que ahora es un lugar donde se reinyecta agua de formación.

Donald: El agua de formación es esa agua fósil que está ahí desde el momento en que empieza la formación del petróleo mismo, ¿no? Entonces, el momento que extraes el petróleo también viene estas aguas de formación y estas aguas son altamente tóxicas

Joseph: Son aguas con una alta salinidad y que se van reinyectando, reinyectando…

Donald: El mismo hecho de ser altamente saladas, altamente tóxicas, mata todo lo que es la vida acuática. Entonces por eso se considera un agua altamente peligrosa…

Joseph: Después fuimos al Pozo Aguarico 4, que para mí fue como el lugar más impresionante, porque uno se va adentrando en el bosque, caminas varios, varios minutos en el bosque.

Donald: Aquí nos encontramos en el pozo Aguarico 4. Hablaban antes de lo famoso que es porque es… Ésta es exclusivamente la operación de Chevron. Aquí Petroecuador no sacó un solo barril de petróleo, así que todo el petróleo que van a ver acá es exclusivamente de ellos, es de Chevron. Esto es lo que indica realmente, como operó aquí en este pozo fueron todos los pozos, y el diseño fue lo mismo para todos. Este pozo fue perforado en el año de 1974 y abandonado en el año de 1984. Sólo produjo petróleo 10 años y pasó a secarse.

Joseph: Cuando ya se terminó de extraer el petróleo, pues se puso tierra encima, se puso como maleza encima.

Donald: Aquí vamos a ver unas piscinas abiertas, así como eran las 880 piscinas que construyó Texaco acá. Este es un claro ejemplo de cómo las construyeron.

Joseph: Y Son piscinas abiertas, son una especie de agujeros. Del tamaño de esas piscinas que uno arma fuera de su casa, esas piscinas grandes, redondas, ¿verdad? Donde puede caber una familia y chapotean los niños. Ya, de ese tamaño era.

Donald: Así que ahorita vamos a ver si nos trasladamos a una de las tres piscinas que hay acá de petróleo.

Joseph: Y aparentemente uno diría bueno, no hay nada, ¿no? Pero eso es mentira, porque uno se, uno camina sobre eso y es como si caminara sobre una cama inflable, como esas camas de agua.

Donald: ¿Ya? Bien. Esto es una piscina. Aquí ha crecido la vegetación. Ustedes pueden notar que no tienen ni geomembrana, ni hormigón, ni plástico para poder proteger el subsuelo, está directamente protegida. Y lo que decían los abogados de Chevron es que esto, como es arcilla, ¿sí?, como esto es arcilla, entonces el petróleo no migra. Pero todo el agua que se mezcla con el petróleo, automáticamente se contamina. Y es ahí cuando va contaminando el agua subterránea aquí. Entonces esta es la profundidad de la piscina.

Joseph: Y me acuerdo mucho de esta imagen de Donald…

Donald: Yo voy caminando por un palo. No quiero que me sigan, por si acaso.

Joseph: Metiendo un palo, un palo largo, hasta el fondo del pozo y cuando lo saca pues sacaba petróleo.

Donald: Lo que les decían antes. Esto es lo que hace peligroso. Y el petróleo aquí está debajo de esta capa que se ha crecido. Entonces hay que meter un palo para poderlo extraer. Trajeron guantes, ¿no?

Joseph: Y tuve la oportunidad de tocar el petróleo, que es como una especie, como de, si, pues como de chicle espeso negro que se te pega a las manos. Y el olor es fuerte, es muy fuerte. Era muy impresionante, porque ahí tú podías entender, claro, estas empresas terminan de extraer el recurso, y muchas veces, no les importa qué dejan detrás, ¿no? O sea, el recurso se acaba porque es un recurso natural, se acaba. Pero después, no nos preguntamos qué ocurre después con ese territorio, con ese lugar ¿no? Entonces, obviamente genera una cantidad de contaminación que ahora vemos los efectos en la salud de las personas y demás. Me acuerdo que después caminamos o bajamos por una colina unos metros más hacia abajo y veíamos como muchos de esos residuos tóxicos se había filtrado hacia un arroyo. Y veíamos sobre el arroyo una película, como de grasa, de grasa, de oscuridad sobre el agua.

Donald: ¿Ahora entienden por qué cuando les digo yo que las mujeres tienen mucho cáncer al útero es porque pasan horas metidas en el río? Es esto. De aquí a más abajo hay algunos caseríos. Estas aguas están cayendo al estero de este río sin nombre, y ahí están. Vienen incluso de Shushufindi a lavar la ropa ahí, y luego va al río Heleno, al Guárico, se hacen un montón de conexiones, ¿no? Entonces… Y no habiendo más, no tienen más a dónde. Y por eso mi hija siempre cuando te dice: tengo el río al lado de mi casa y no lo puedo utilizar, es justamente porque nosotros le enseñamos que el río no es un acto para que ella pueda bañarse o nadar y todo. Las dos veces que la metimos ahí fue, una cuando tenía seis meses. Eso fue una granazón en el cuerpo, tenaz, que le pegó. Y la otra era cuando tenía cuatro años de edad. A los seis días estaba todo el cuerpo llenita de granos y desde ahí te debe haber indicado que tiene unos granitos que tenía en la nariz, manchas en el cuerpo. Imagínate de

cuatro años a ahora que tenía 15 años, son 11 años que esas manchas no se le quitan.

Joseph: ¿Qué te pareció lo que acabamos de ver?

Alumna biología: ¡Uff! ¿Súper loco, no?

Silvia: Después del tour, Joseph habló con las estudiantes universitarias de biología que estuvieron con él ese día en el recorrido.

Alumna biología: Ver directamente el agua que sale, ¿no? Estoy segura de que si es que las autoridades vieran eso… Bueno, no sé, tal vez sería un poco más claro para ellos lo que está pasando, ¿no?

Alumna: Bueno, primero, lo primero que sentí es indignación, porque las personas que fueron afectadas no son escuchadas.

Alumna: En general, en la escuela te cuentan que es un país petrolero, ¿no? Que hay explotación petrolera, que nosotros vendemos petróleo, pero no te cuentan como que la parte que hay detrás de todo esto, ¿no? Que hay contaminación ambiental, que hay ecocidio, que hay genocidio porque prácticamente están acabando con comunidades que antes aquí vivían y que desaparecen, y todo es debido y va desde la raíz de esta explotación. Entonces, súper fuerte. Y no te cuentan…

Eliezer: Hacemos una pausa y volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta.

Eliezer: Joseph, el toxic tour que hiciste, claro, deja claro que la contaminación que ha causado el petróleo sigue afectando a las personas que viven en esta zona, porque no han reparado realmente. Ahora, ¿pudiste hablar con gente que todavía que vive ahí cerca de petroleras que están activas?

Joseph: Pude hablar con el padre de una de las Guerreras por la Amazonía, a quien yo conocí en el Tena, en este taller de incidencia que daba Amnistía Internacional. Cuando yo estuve en ese taller, conocí al padre de Jamileth Jurado, al señor Frank. Ahora es un hombre que está, digamos, jubilado. Pero antes era un especialista en determinar cuándo una tubería tenía un agujero, tenía una filtración. Él ha visto como ha venido llegando la industria petrolera a esa zona del Ecuador. Entonces, por eso es una persona muy informada y que sabe de lo que está hablando. Y él muy gentilmente me dijo: “Mira, si tú quieres ver realmente también lo que está pasando en esa zona, pues anda a visitarme a mi casa”. Y su casa queda en Shushufindi.

Frank Jurado: En el corazón de la Amazonía petrolera. Ahí está Shushufindi,

Joseph: Es una localidad que está como a una hora de Lago Agrio en auto.

Frank: Mire, aquí está. Tenemos la plataforma. Entonces la casa no está a 100 metros. Tal vez esté a unos 80 metros, la casa de la plataforma.

Joseph: Ellos viven pues en una zona rural, al costado de una plataforma petrolera y también muy cerca de un relleno sanitario. O sea, tienen una afectación por todos lados.

Frank: La empresa petrolera, cuando compró a mis suegros dos hectáreas, dijeron que iban a comprar, que iban a perforar un solo pozo. Pero sin embargo, se perforaron siete pozos. O sea, siempre son gente mentirosa. Siempre han sido gente que les gusta engañar. Nunca socializan las cosas así para que uno tenga conocimiento y pueda evaluar quizás el potencial de riesgo que pueda tener. Entonces nosotros tenemos que vivir con los resultados de la explotación petrolera.

Joseph: Y él ya lleva muchas décadas viviendo en ese lugar. Es una plataforma que hace un ruido terrible, terrible, un ruido a veces ensordecedor conforme uno se va, se va acercando.

Frank: Mucha bulla, sí… Pero lo que tenemos aquí junto a la plataforma es ahí un área de químicos. Pero esto no se soporta cuando hace sol. Es unos olores fortísimos y conforme las corrientes de aire van de un sector a otro, esto viaja con las corrientes de aire…

Joseph: Y estos olores les generan dolores de cabeza, mareos. Y lo más increíble es que en medio de esos olores y ese ruido industrial, uno puede escuchar incluso los cantos de los pájaros. Eso es muy contradictorio también.

Frank: Acá vamos a ver un desagüe que tiene la plataforma. Los tiene al lado de allá y al lado de acá. Entonces…

Joseph: Unos metros más allá también hay un desagüe, ¿no? Que es por donde van saliendo, digamos, los residuos. Que eso también se va filtrando por la tierra y va contaminando las fuentes de agua.

Frank: Y la gente ha muerto por eso, porque se ha acostumbrado a beber esa agua, porque aquí no ha habido más agua que beber, el agua de lluvia y el agua de los afluentes. Y se bañan aquí. Y uno se adapta.

Joseph: Entonces es bien impresionante cómo un ser humano puede vivir cerca de un lugar así, ¿no? Entonces, claro. Pero él me dice, pues yo no me puedo ir a ningún lado.

Frank: Aparentemente estamos en un sector muy rico, donde hay petróleo, la explotación. Y aquí salen miles de barriles de petróleo diarios. ¿Pero de qué nos sirve a nosotros si nosotros vivimos en la miseria? Y tras de vivir en la miseria, vivimos contaminados de diferente índole. Vivimos jodidos, explotados, pero ahí no tenemos dónde más ir a vivir.

Joseph: La gente que contratan, por ejemplo, para poder cuidar ese lugar, es gente de afuera. Ni siquiera es que le den trabajo al señor por tener el pozo tan cerca de su casa. Entonces como que no hay ninguna ventaja para él. Lo que hay simplemente son cosas negativas. El ruido, la contaminación.

Frank: El Estado no se conduele, no nos da, qué se yo, otra tierra en otro lugar. Acá no hay gente mala, y si la gente se rebela, la gente se porta malcriada, y si la gente alza la voz, es porque tiene justa razón.

Joseph: Don Frank me hablaba de lo orgulloso que se siente de su hija. De Jamileth. Cómo siendo tan jovencita ella puede levantar su voz, puede hablar de lo que está ocurriendo allí.

Frank: Para nosotros como padres es un orgullo que nuestros hijos estén participando en esta labor social, diría yo, social. ¿Por qué? Porque ellos están pidiendo de forma global. para todos los sectores. Ellas tienen su derecho, están en su derecho de reclamar, de alzar la voz para estas autoridades indolentes que no se preocupan, que no hacen conciencia.

Jamileth Jurado: Mi nombre es Liberth Jamileth Jurado Silva, tengo 17 años de edad y represento al grupo de accionantes del caso Mecheros de las nueve niñas.

Joseph: La madre de Jamileth, la exesposa de Frank, también está enferma de cáncer.

Jamileth: Bueno, llegué a ser parte porque soy hija de una paciente oncológica. Mi mamá se llama Fanny Silva. Se dedica a los quehaceres domésticos y es paciente de cáncer, ya 10 años.

Joseph: ¿Qué tipo de cáncer tiene ella?

Jamileth: Cáncer al útero.

Silvia: A mí algo que me impresiona mucho del Caso Mecheros es que las demandantes sean niñas, ¿no? Y niñas tan jovencitas. ¿Por qué? ¿Por qué lo hicieron así?

Joseph: Bueno, lo que me contaba Pablo cuando hablé con él…

Pablo Fajardo: Bueno, mi nombre es Pablo Fajardo Mendoza y trabajo desde hace 32 años en la Unión de Afectados por Texaco, UDAPT, en sus siglas, como abogado, como asesor jurídico del colectivo en ese caso.

Joseph: Era de que para la organización era muy importante que se entienda que este problema va a afectar el futuro de la población que vive en esa zona.

Pablo: Ya viendo lo que teníamos de información, nos encontramos que en la zona tenemos muchos casos de cáncer, una tasa de cáncer que supera de largo el promedio nacional. Y de esos casos de cáncer, las cosas que más nos preocupaba que más veíamos era que de cada 100 casos de cáncer que encontrábamos, 72 son mujeres. Entonces, claro, es un promedio, un dato alarmante, porque el promedio nacional es mitad-mitad prácticamente y a veces levemente más en hombres. Pero acá tenemos: de cada cuatro, tres son mujeres y uno es hombre. Entonces es un caso tremendamente preocupante.

Jamileth: Entonces se puede decir que nosotras somos más vulnerables. En este caso venimos de madres, hermanas y familias mujeres dentro del grupo de las chicas, con cáncer. Nosotros podemos ser las víctimas del futuro, hasta incluso nuestros hijos si esto no cambia.

Pablo: Entonces salió la idea de que sean niñas las que demanden, ¿no? Lo planteamos a algunas familias y dijeron encantado de la vida, ¿sí? Entonces las niñas decidieron y decidieron, junto con su familia, ser demandantes en este caso.

Joseph: Ellas, digamos, asumieron esta lucha, de ser el rostro de esta lucha. En particular Jamileth y Leonela, que son las más elocuentes, son las más empoderadas, digamos, ¿no? Es más, a mi me contaba Donald que Leonela le exigió, que ella quería ser una vocera de esta lucha.

Eliezer: Lo que queda claro por lo que cuentas y por lo que dicen ellas es obviamente que no es que las estén usando, sino que ellas abanderan, digamos, este reclamo, ¿no? Jamileth habla tan claro sobre este caso, igual que Leonela, que conocimos en Tena, ¿no? Y también es tan joven. ¿Qué quiere hacer ella? ¿Qué planes tiene para el futuro?

Joseph: Ella piensa estudiar medicina.

Jamileth: Y pues ayudar a muchas personas, que muchas veces mueren aquí, mueren dentro de sus comunidades, porque sabemos de que la economía no está tan bien. Es demasiado caro la medicación de un paciente oncológico. Tras de eso, le toca ir y venir en la ciudad, Entonces es muy difícil. Entonces me gustaría especializarme un poco en eso y venir acá y atender a esas personas. Y luego de eso, pues, seguir en esta lucha y apoyar a otras luchas más. El activismo, no lo pienso dejar.

Joseph: Creo que lo extraordinario en ella es que a pesar de que incluso hay presiones políticas, a pesar de que han dicho que ellas están siendo utilizadas, a pesar de que incluso, por ejemplo, una de las niñas como Leonela tuvo un atentado cerca de su casa. A pesar de que amenazan a sus padres. A pesar de todo eso, ellas siguen adelante. Y siguen levantando la voz.

Jamileth: Porque hasta el último momento que se acabe la contaminación, yo creo que nosotras debemos luchar porque nuestras familias, las familias de nuestras familias, los hijos de nuestros hijos van a vivir en contaminación. Y mientras haya un sufrimiento siempre va a haber una persona que se va a poner adelante y va a sacar la cara por todos.

Joseph: Es muy diferente la protesta de la lucha, ¿no? La protesta es un momento específico, un acontecimiento específico en las calles, en la ciudad, en pos de una causa. Pero la lucha es otra cosa. La lucha es un proceso histórico, que tiene una serie de etapas y una serie de idas y venidas. Entonces ellas no están protestando nomás. Ellas están luchando. Y esa diferencia a veces uno desde la ciudad no la comprende.

Silvia: Hacemos una última pausa y volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Joseph: Esto ya, digamos, es ya el parque ya.

Holmer: Sí…

Eliezer: Al final de su recorrido por la Amazonía ecuatoriana, camino a la frontera con Perú, Joseph visitó el Parque Nacional Yasuní, el área protegida más grande del Ecuador.

Silvia: Cubre una superficie de casi 10 mil kilómetros cuadrados: eso es más que Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Santiago de Chile, Lima, Sao Paulo, Bogotá, La Paz, Ciudad de México, Caracas y Quito juntas.

Joseph:. ¿Cuántas hectáreas me dijiste que tiene el parque?

Holmer: 1.022.376. Si no me equivoco…

Joseph: Y bueno, luego de pasar unos días en Lago Agrio y de conocer la lucha de la UDAPT, una madrugada tomé un taxi que me llevó durante una hora por la carretera hasta la ciudad de Coca, también llamada Francisco de Orellana, donde hay un puerto. Y en ese puerto tomé una lancha rápida que me llevó a lo largo de unas 5 horas más o menos río abajo, por el río Napo, hasta la localidad de Nuevo Rocafuerte. Ahí en ese lugar fue Holmer a recogerme en su bote, para llevarme a conocer a su familia que está en el parque Yasuní.

Tuve la oportunidad de pasar un fin de semana en la comunidad de Llanchama con Holmer, un guardaparques. Es un tipo joven, que tiene mucho tiempo ya viviendo en ese lugar. Es un guía de turismo, pero durante los últimos años ha trabajado como guardaparques del Yasuní.

Holmer: En las culturas nuestras lo consideramos al Parque Nacional Yasuní como una de nuestras farmacias, nuestro mercado, nuestra casa, porque en ella encontramos todo. En un metro cuadrado puede haber más de mil especies, tanto sea insectos, plantas, hongos.

Joseph: Y es impresionante entrar al Yasuní, es impresionante, ¿no? Por la cantidad de estímulos que uno va percibiendo, los cantos de las aves, los monos, los árboles, el aire que uno respira. Es increíble en verdad ese lugar.

Holmer: Si en algún momento se llegara a contaminar o a destruir totalmente, es como que nos quitaran todo a nosotros, las culturas.

Joseph: Es un lugar que ha sido considerado como uno de los lugares de mayor biodiversidad del planeta. De hecho, la UNESCO en el 89 lo declaró como Reserva Mundial de la Biosfera. Es un lugar muy importante, por la cantidad de especies de fauna y flora. Pero también porque en ese lugar viven pueblos indígenas originarios, viven los waorani, los tagaeri. Al día de hoy ha visto o ha recibido las presiones de parte del Estado ecuatoriano para que se explote el petróleo de ese lugar. Obviamente con las consecuencias que eso genera. Entre las operaciones, por ejemplo, de Petroecuador, que es la petrolera estatal de ese país, está el bloque 43, que opera en el parque. Eso, por supuesto, genera una afectación no solamente a nivel de la contaminación posible del agua, sino también el ruido. El ruido también, las máquinas generan un ruido, una contaminación sonora que afecta a las especies que viven ahí. Una cosa que yo pude averiguar de los datos, de la investigación, es que esta explotación petrolera es simplemente como un eslabón de una cadena mucho más grande. En los últimos años se han conseguido como 21 bloques de extracción petrolera dentro de áreas de conservación del Ecuador. Lo que suma, según lo que tengo aquí anotado, son más de 7.000 kilómetros cuadrados de territorio en el Ecuador. Entonces, en el año 2023 se hizo una consulta popular. Los ciudadanos ecuatorianos votaron en esta consulta popular a favor de que se quedara el petróleo del Yasuní bajo tierra, es decir, que no se explotara. Con un 58.9% del total de los votos.

Holmer: Para ciertas personas, quienes estuvimos luchando en eso para que no se continúe con la explotación petrolera, pues fue una alegría, pero que hasta ahora no, no se está cumpliendo. Se sigue todavía con el trabajo de extracción del petróleo dentro del Parque Nacional Yasuní.

Joseph: Luego de esa votación, la Corte Constitucional dio un año de plazo al gobierno ecuatoriano y a Petroecuador, para cerrar este Bloque 43 en el Yasuní. Para poner fin a las actividades, para que se quitara esas instalaciones que están ahí. Pero durante ese tiempo pues no se ha avanzado casi nada, ¿no? Se entregó, de hecho, un plan de cierre a la Corte Constitucional. No de un año, sino de cinco años. El gobierno dijo: Bueno, en cinco años lo voy a cerrar. Pero hasta ahora, según la información que tengo, solo se ha cerrado el 2% de los pozos que hay en el bloque 43. O sea, solamente se han cerrado cinco pozos de 247.

Eliezer: ¿Y el miedo es que el Yasuní se pueda convertir en otro Lago Agrio?

Joseph: Por supuesto. Por supuesto. Es un miedo evidente que tienen las personas que viven en ese lugar.

Holmer: Si ahora nosotros no, no actuamos, no hacemos algo por la conservación, pues… Esto se va a volver un desierto con el tiempo, donde la mayor parte de gente irá muriendo por el tema de la contaminación.

Joseph: Yo me acuerdo mucho de algo que me contaba un amigo kofán, un jovencito kofán que ni siquiera tiene 30 años, que se llama Andy Nixon. Es como un dirigente, como un activista, por el medio ambiente ahí en Lago Agrio. Y él me decía que antes, ese lugar los gringos que llegaron con Texaco le pusieron de nombre Sour Lake, que es el Lago Agrio, digamos, por el agua que se sacaba de esos pozos petroleros, que es un agua salada, agria, digamos. Pero lo que me contaba Andy Nixon era que los primeros kofanes, sus antepasados, ya le habían puesto un nombre a ese territorio. Se llamaba Amisacho. Que amisacho en lengua kofán significa lugar de guadas, que es una variedad de bambú enorme y espinoso. Entonces ese lugar que antes era un lugar de guadas, entregada totalmente a la conservación por estos mismos pueblos originarios, se convirtió en un Sour Lake, un lago agrio, un lugar devastado y contaminado por los mecheros, por las petroleras. No sé, cuando pienso en Yasuní me acordaba mucho de lo que me decía mi amigo Andy: se puede convertir también en eso. Una señal de que eso podría pasar si no hacemos nada al respecto es esta reciente decisión del gobierno ecuatoriano de fusionar el Ministerio del Ambiente con el Ministerio de Energía y Minas, que ahora la función de fiscalizar o de encargarse de que las empresas respeten las medidas medioambientales para proteger el territorio, el bosque, el agua, ahora ya no va a estar en manos de una institución aparte, ¿no? Sino va a estar en manos de quienes dan las mismas concesiones. Y eso es peligroso. Eso atenta contra un verdadero ejercicio de justicia para las poblaciones que viven en ese lugar. El asunto es que hay gente todavía, como estas personas que conocí en Ecuador que está todavía luchando por esto. Y yo creo que se va a evitar que se convierta en un lago agrio. Se va a evitar y se puede evitar. Al menos esa es la convicción que yo tengo. La población del Ecuador ya se ha levantado antes. Los pueblos indígenas se han levantado antes y se van a volver a levantar si es que si es que esto no cambia. Estoy seguro de eso.

Silvia: En el próximo episodio…

Edgar Isuriza: Hablábamos de 75 dragas, hoy ya tenemos información que son 120 dragas.

Marcelina Aguilar: ¿Sabes qué es lo que tienen miedo los dragueros? A que nosotros nos organicemos como comunidad. La comunidad tiene más fuerza.

Claudia Vega: Lo que no explican los mineros es que después que terminen de sacar el oro, el bosque está contaminado, el agua está contaminada, y el costo en la salud de la población es bien alto.

Eliezer: Este episodio lo produjo Silvia con la reportería de Joseph y la investigación de Rosa Chávez Yacila. Lo editó Daniel Alarcón. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido es de Elías González con música de Remy Lozano.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Soy Eliezer Budasoff. Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

This series was produced with the support of Movilizatorio and Alianza Potencia Energética Latam

Wilmer Lucitante: To them, we’re a thorn in their side because we do this type of work, which is about exposing the bad practices they carry out—their irresponsibility.

Eliezer Budasoff: The speaker is Wilmer Lucitante, a Cofán monitor with the Union of Those Affected by Texaco’s Oil Operations (UDAPT). It’s an organization that brings together dozens of communities that have been harmed by the oil industry in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Wilmer: To the oil companies, we’re a thorn in their side because we tell the truth about the contamination. We demand our rights.

Joseph: He’s 34 years old, a father of two children. And he lives—in fact, he lives near a flare, one of those structures that release toxic gases.

Silvia: Journalist Joseph Zárate, our guide through this journey across the Amazon, met with Wilmer in Lago Agrio, a city in the province of Sucumbíos. It’s in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon, very close to the border with Colombia.

Joseph: It’s a very, very particular place because it used to be the ancestral territory of several indigenous groups, but particularly the Cofán, who were gradually displaced by the oil industries, especially from the mid-20th century onward. So I went there because that’s where the Amazon Warriors are from.

Eliezer: The group of girls and teenagers who are activists defending their territories from oil contamination. We met one of them, Leonela, in the previous episode. They’re the girls who won a lawsuit to eliminate the flares near their homes.

Joseph: So I wanted to learn a little more about the reality and about the place where they live, but above all to understand why they were fighting, right? In their activism.

Wilmer: The thing is, they haven’t eliminated them until now. The sentence clearly states that they must eliminate the flares that are near the populations. And they haven’t done it.

Joseph: And he was explaining to me that he was building his house, and he showed me where he was building his house, and I realized that nearby, just meters from his house, there wasn’t just one flare anymore—there were two more. In other words, the flares had increased. And I asked him, “Hey, but why are you building your house here? Why don’t you leave? If I were you, I’d leave.”

Joseph: I wanted to ask you. How does that make you feel? As a father, having your children near the flare.

Wilmer: At first, I thought about going somewhere else, right? And getting away from places with contamination. But I started thinking… It’s like running away, right? It’s abandoning. How are we going to let them do whatever they want? Because we can’t allow this type of contamination to continue for five more years, 10 more years, 50 more years.

Silvia: This is Amazonas adentro, a series from El hilo, from Radio Ambulante Studios. Episode 2: The Chernobyl of the Amazon.

Joseph: One of the objectives I had in Lago Agrio was to be able to take a tour of the disaster, right? There’s a tour called the Toxic Tour that UDAPT organizes—this association that defends those affected by Texaco’s oil spills in that area—to somehow raise awareness, right? About the terrible effect that this oil industry has in that part of Ecuador.

Donald Moncayo: It’s a way of reaching people, right? We don’t have such a big, powerful media to reach them. And above all, it’s not the same as being there, smelling it there, seeing how nature also does its part trying to clean, trying to remedy what we humans have destroyed, right? I’m interested in people coming, learning about it, knowing about it.

Joseph: Donald Moncayo is an environmental activist. He’s a farmer. He has dedicated himself to leading and coordinating UDAPT. So he’s a very brave man. A man who has risked many things in the name of his struggle. He has a daughter we’ve heard, named Leonela.

Joseph: You were born here.

Donald: Yes. I was born on November 20, 1973, 200 meters from the second well that Texaco drilled here, Chevron here. So I saw everything. I’ve seen all of this. Nobody told me about it. I lived it.

Joseph: In fact, his mother died of cancer. For him, defending this cause to achieve reparations for those affected isn’t just something typical of an activist’s work. For him, it’s something personal. And it’s very similar to the story Diego Robles told me, who also lost his mother. And it’s also very similar to what the children from Tena told me, the Yaku Churi, because they too, in some way, saw the place where they learned to swim, where their parents go to wash clothes, to get water from the river, to cook. So when you talk with people like Donald, you see in their way of being, in their way of speaking, that this isn’t simply work for people who want to care for the environment, or who want to protect the lives of trees, or animals, or rivers. It’s not only about that. There’s something personal that runs through them deeply. Something that has fractured something very deep in their lives, their identity, their affections. And in that fracture is where this impulse arises, this fire of wanting to raise their voice, of wanting to do something about it.

Donald: Going on these Toxic Tours is that, right? Going to really tell what happened and precisely to awaken young people to the fact that transnational companies aren’t really an alternative. I very much doubt that a transnational company enters your country, enters your town, enters your community to leave you benefits.

Eliezer: Joseph, let’s talk a little about the Toxic Tour. But before you tell us about that journey, we’d like to understand more about what happened in this area and why they do this tour.

Joseph: This place is the site in Ecuador that experts have called the worst oil disaster in the world. They’ve even called it the “Chernobyl of the Amazon,” due to the disastrous contamination left by this transnational corporation, by Texaco, which is now called Chevron. So for almost 30 years, from the 1960s until 1990, Texaco-Chevron dumped more than 16 billion gallons of toxic waste in northern Amazonian Ecuador, that area I mentioned, which is Lago Agrio. So these toxins have left dangerous residues in hundreds of open pits that were excavated in the forest floor, right? In the forest floor itself. The local population suffers from cancer, sometimes children suffer from birth defects. A series of health problems that to this day the Ecuadorian State hasn’t been able to help resolve. So in 1993, a class action lawsuit against Texaco was initiated in New York. And this lawsuit, led by UDAPT, was representing about 30,000 inhabitants of that area of Ecuador who have been affected by oil extraction activities in Lago Agrio. But it wasn’t until 2011—many, many years later—that the Provincial Court in Sucumbíos, in Ecuador, finally issued a ruling against Chevron for the damages, for the extreme negligence with which this company operated in exchange for the profits it expected to receive. This ruling also ordered the company to pay 9.5 billion dollars in costs to repair the damages from all that this oil exploitation caused.

Donald: The Chevron case is about them having to pay, about them having to really do remediation, a cleanup adequate for living with dignity, which is what we’re seeking with this. Since what they came to do was to really destroy our common home, where we live.

Joseph: But to this day, well, not a single dollar has been paid.

In 2013, for example, Ecuador’s Court of Justice ratified the conviction. In 2018, it ratified the sentence again, stating that payment must be made. But until now, nothing has been paid—the disaster hasn’t been cleaned up, the waste continues contaminating that area of the Ecuadorian Amazon. So nothing has been repaired. In fact, according to the organization Amazon Watch, until 2024, about 13 years after the sentence, Chevron would have obtained more than 200 billion dollars in profits. And until now, it hasn’t paid anything.

Donald: And that’s why. It leads us to keep fighting, to keep really seeking that the culprit of all this doesn’t play the victim, but really assumes their responsibility, because it’s their responsibility to leave things just as they found them before entering to destroy everything.

Silvia: How does the toxic tour begin? How do they prepare you for this journey?

Joseph: Well, first of all, when you want to do the Toxic Tour, you simply go to UDAPT’s offices, right? They’re very modest offices where there are always volunteers. You’ll always find Donald there. There’s an entire room with all the files from the lawsuits, kept there. And it’s impressive because it’s one after another, files upon files with evidence, with records, with people’s testimonies. I had the opportunity to see it, and it’s very impressive because you can grasp the amount of work and years of struggle. And well, the first thing you have to remember is that you need to bring boots, right? I didn’t bring any. Because, well, you’re going to step on a lot of water and mud and things mixed with oil. But well, I remember the Tour started with opening words from Pablo Fajardo.

Pablo Fajardo: When a river is contaminated, it affects the entire environment: the mammals, the fish, the culture of the peoples, the environment, the water—everything directly there.

Joseph: Pablo is a lawyer and legal advisor for UDAPT; he’s an activist who has spent many years defending this cause. And that morning on the bus, before departing, he explained to us a little about the context of what we were going to see that morning on the Toxic Tour.

Pablo: We have 32 years of trial against Chevron. We won the trial in all instances of the country. There are four conviction sentences against Chevron.

Joseph: And he’s a very, very lucid guy. Very clear, very straightforward too. Sometimes, in his way of speaking, I think he’s even more direct than Donald. I think it’s because of his tone of voice. Donald has a slightly softer voice. Pablo is very direct.

Pablo: So welcome here again, this is a very short summary; today you’ll see much more in the field, but I also invite you to… Hopefully, when you return with more information, we can also see how we can help in these struggles. First, so there’s justice. Second, to prevent more damage from other companies, to denounce them too, and so governments understand that life is worth much more than oil. Yes? Thank you very much and have a beautiful day. Enjoy it. Yes. You’re going with Donald, who’s the boss now.

Donald: Raise your hand if anyone’s missing.

Joseph: And well, so we were on the bus with a group of biology students from the Universidad Central de Ecuador. There were about twenty very young women, most of whom had never visited the Amazon or knew about this problem.

Donald: Drilled in 1969…

Joseph: First we visited an old oil well that was about half an hour from UDAPT’s office, where from the mid-60s to the mid-80s, oil was extracted. Now there’s no more oil in that place; instead, it’s now a place where formation water is reinjected.

Donald: Formation water is that fossil water that’s been there since the moment the formation of the oil itself begins, right? So when you extract the oil, this formation water also comes out, and these waters are highly toxic.

Joseph: They’re waters with high salinity that keep getting reinjected, reinjected…

Donald: The very fact of being highly saline, highly toxic, kills everything that is aquatic life. So that’s why it’s considered highly dangerous water…

Joseph: Then we went to Well Aguarico 4, which for me was the most impressive place because you go deep into the forest; you walk for several, several minutes in the forest.

Donald: Here we are at Well Aguarico 4. They talked before about how famous it is because… This is exclusively Chevron’s operation. Here Petroecuador didn’t extract a single barrel of oil, so all the oil you’re going to see here is exclusively theirs, it’s Chevron’s. This really indicates how they operated here at this well—all the wells were the same, and the design was the same for all. This well was drilled in 1974 and abandoned in 1984. It only produced oil for 10 years and then dried up.

Joseph: When the oil extraction finished, well, they put dirt on top, they put vegetation on top.

Donald: Here we’re going to see open pits, just like the 880 pits that Texaco built here. This is a clear example of how they built them.

Joseph: And they’re open pits, a kind of hole. The size of those pools you set up outside your house, those big, round pools, right? Where a family can fit and kids can splash around. Yeah, it was that size.

Donald: So now we’re going to see if we can go to one of the three oil pits here.

Joseph: And apparently you’d say, well, there’s nothing, right? But that’s a lie, because when you walk on it, it’s like walking on an inflatable mattress, like those water beds.

Donald: Ready? Good. This is a pit. Vegetation has grown here. You can notice they don’t have geomembrane, concrete, or plastic to protect the subsoil; it’s directly exposed. And what Chevron’s lawyers said is that this, since it’s clay, right? Since this is clay, the oil doesn’t migrate. But all the water that mixes with the oil automatically becomes contaminated. And that’s when it contaminates the groundwater here. So this is the depth of the pit.

Joseph: And I remember this image of Donald very well…

Donald: I’m walking on a stick. Don’t follow me, just in case.

Joseph: Sticking a stick, a long stick, to the bottom of the pit, and when he pulled it out, well, he pulled out oil.

Donald: What I told you before. This is what makes it dangerous. And the oil here is beneath this layer that has grown. So you have to stick a stick in to be able to extract it. You brought gloves, right?

Joseph: And I had the opportunity to touch the oil, which is like a kind of thick black gum that sticks to your hands. And the smell is strong, very strong. It was very impressive because there you could understand—of course, these companies finish extracting the resource, and many times they don’t care what they leave behind, right? I mean, the resource runs out because it’s a natural resource; it runs out. But then we don’t ask ourselves what happens afterward with that territory, with that place, right? So obviously it generates an amount of contamination that we now see the effects of in people’s health and so on. I remember that afterward we walked or went down a hill a few meters further down, and we saw how many of those toxic residues had filtered into a stream. And we saw on the stream a film, like grease, like a darkness on the water.

Donald: Now do you understand why when I tell you that women have a lot of uterine cancer, it’s because they spend hours in the river? It’s this. From here downward there are some settlements. These waters are falling into the stream of this nameless river, and there they are. They even come from Shushufindi to wash clothes there, and then it goes to the Heleno River, to the Aguarico, they make a bunch of connections, right? So… And having nothing more, they have nowhere else. And that’s why my daughter always says when she tells you: I have the river next to my house and I can’t use it—it’s precisely because we taught her that the river isn’t suitable for her to bathe or swim and all. The two times we put her in there, one was when she was six months old. That was a terrible rash on her body that she got. And the other was when she was four years old. Six days later, her whole body was full of bumps, and since then you should have noticed she has little bumps she had on her nose, spots on her body. Imagine from four years old to now that she’s 15 years old—that’s 11 years that those spots haven’t gone away.

Joseph: What did you think of what we just saw?

Biology student: Wow! Super crazy, right?

Silvia: After the tour, Joseph spoke with the university biology students who were with him that day on the journey.

Biology student: Seeing the water that comes out directly, right? I’m sure that if the authorities saw that… Well, I don’t know, maybe it would be a little clearer to them what’s happening, right?

Student: Well, first, the first thing I felt was indignation because the people who were affected aren’t being heard.

Student: In general, at school they tell you that it’s an oil-producing country, right? That there’s oil exploitation, that we sell oil, but they don’t tell you about the part behind all this, right? That there’s environmental contamination, that there’s ecocide, that there’s genocide because they’re practically wiping out communities that used to live here and are disappearing, and it’s all due to and goes back to the root of this exploitation. So, super intense. And they don’t tell you…

Eliezer: We’ll take a break and come back.

Silvia: We’re back.

Eliezer: Joseph, the toxic tour you did clearly shows that the contamination caused by oil continues affecting the people who live in this area because they haven’t really repaired anything. Now, were you able to talk with people who still live near active oil operations?

Joseph: I was able to speak with the father of one of the Amazon Warriors, whom I met in Tena, at this advocacy workshop given by Amnesty International. When I was at that workshop, I met Jamileth Jurado’s father, Mr. Frank. He’s a man who is, let’s say, retired now. But before, he was a specialist in determining when a pipeline had a hole, had a leak. He has seen how the oil industry has been arriving in that area of Ecuador. So that’s why he’s a very informed person who knows what he’s talking about. And he very kindly told me: “Look, if you really want to see what’s happening in that area, come visit me at my house.” And his house is in Shushufindi.

Frank Jurado: In the heart of the oil Amazon. That’s where Shushufindi is.

Joseph: It’s a town that’s about an hour from Lago Agrio by car.

Frank: Look, here it is. We have the platform. So the house isn’t 100 meters away. Maybe it’s about 80 meters from the platform.

Joseph: They live in a rural area, next to an oil platform and also very close to a landfill. So they’re affected from all sides.

Frank: The oil company, when they bought two hectares from my in-laws, said they were going to buy, that they were going to drill just one well. But nevertheless, seven wells were drilled. So they’re always lying to people. They’ve always been people who like to deceive. They never communicate things properly so you have knowledge and can perhaps evaluate the potential risk you might have. So we have to live with the results of oil exploitation.

Joseph: And he’s been living in that place for many decades. It’s a platform that makes a terrible noise, terrible, a sometimes deafening noise as you get closer.

Frank: Lots of noise, yes… But what we have here next to the platform is a chemical area there. But this is unbearable when it’s sunny. It’s extremely strong smells, and as the air currents go from one sector to another, this travels with the air currents…

Joseph: And these smells give them headaches, dizziness. And the most incredible thing is that amid those smells and that industrial noise, you can even hear the birds singing. That’s very contradictory too.

Frank: Here we’re going to see the drainage that the platform has. It has them on that side and on this side. So…

Joseph: A few meters away there’s also a drain, right? Through which the waste flows out. That also filters through the earth and contaminates water sources.

Frank: And people have died from that, because they’ve gotten used to drinking that water, because here there hasn’t been any other water to drink—rainwater and water from tributaries. And they bathe here. And one adapts.

Joseph: So it’s very impressive how a human being can live near a place like that, right? So of course. But he tells me, well, I can’t go anywhere.

Frank: Apparently we’re in a very rich area, where there’s oil exploitation. And thousands of barrels of oil come out of here daily. But what good does it do us if we live in misery? And besides living in misery, we live contaminated in different ways. We live screwed, exploited, but we have nowhere else to go live.

Joseph: The people they hire, for example, to guard that place are outsiders. It’s not even like they give the man work for having the well so close to his house. So there’s no advantage for him. What there is are simply negative things. The noise, the contamination.

Frank: The State doesn’t take pity, doesn’t give us, what do I know, other land somewhere else. Here there are no bad people, and if people rebel, if people act badly, and if people raise their voice, it’s because they have just reason.

Joseph: Don Frank spoke to me about how proud he feels of his daughter. Of Jamileth. How, being so young, she can raise her voice, and can speak about what’s happening there.

Frank: For us as parents, it’s a source of pride that our children are participating in this social work, I’d say, social. Why? Because they’re asking for it globally, for all sectors. They have their right; they’re within their right to claim, to raise their voice to these indifferent authorities who don’t care, who don’t become aware.

Jamileth Jurado: My name is Liberth Jamileth Jurado Silva. I’m 17 years old and I represent the group of plaintiffs in the Flares case of the nine girls.

Joseph: Jamileth’s mother, Frank’s ex-wife, is also sick with cancer.

Jamileth: Well, I became part of it because I’m the daughter of an oncology patient. My mom’s name is Fanny Silva. She’s a homemaker and has been a cancer patient for 10 years now.

Joseph: What type of cancer does she have?

Jamileth: Uterine cancer.

Silvia: Something that really strikes me about the Flares Case is that the plaintiffs are girls, right? And such young girls. Why? Why did they do it that way?

Joseph: Well, what Pablo told me when I spoke with him…

Pablo Fajardo: Well, my name is Pablo Fajardo Mendoza, and I’ve been working for 32 years at the Union of Those Affected by Texaco, UDAPT in its acronym, as a lawyer, as legal advisor to the collective in that case.

Joseph: It was that for the organization it was very important for people to understand that this problem is going to affect the future of the population living in that area.

Pablo: Looking at the information we had, we found that in the area we have many cancer cases, a cancer rate that far exceeds the national average. And of those cancer cases, what worried us most, what we saw most, was that out of every 100 cancer cases we found, 72 were women. So of course, it’s an alarming average, an alarming figure, because the national average is practically half and half, and sometimes slightly more in men. But here we have: out of every four, three are women and one is a man. So it’s a tremendously worrying case.

Jamileth: So you can say that we’re more vulnerable. In this case, we come from mothers, sisters, and female family members within the girls’ group, with cancer. We could be the victims of the future, even our children if this doesn’t change.

Pablo: So the idea came up for girls to file the lawsuit, right? We proposed it to some families and they said they’d be delighted, yes? So the girls decided, and they decided together with their families to be plaintiffs in this case.

Joseph: They took on this struggle, of being the face of this struggle. Particularly Jamileth and Leonela, who are the most eloquent, the most empowered, let’s say, right? In fact, Donald told me that Leonela demanded that she wanted to be a spokesperson for this struggle.

Eliezer: What’s clear from what you’re telling us and from what they say is obviously that they’re not being used, but rather that they’re leading this claim, right? Jamileth speaks so clearly about this case, just like Leonela, whom we met in Tena, right? And she’s also so young. What does she want to do? What plans does she have for the future?

Joseph: She’s thinking of studying medicine.

Jamileth: And well, to help many people who often die here, die within their communities, because we know that the economy isn’t doing well. Medication for an oncology patient is very expensive. On top of that, they have to go back and forth to the city. So it’s very difficult. So I’d like to specialize a little in that and come here and care for those people. And after that, well, continue in this struggle and support other struggles. Activism—I don’t plan to leave it.

Joseph: I think what’s extraordinary about her is that despite the fact that there are even political pressures, despite the fact that they’ve said they’re being used, despite the fact that even, for example, one of the girls like Leonela had an attack near her house. Despite the fact that they threaten their parents. Despite all that, they keep going. And they keep raising their voice.

Jamileth: Because until the last moment when the contamination ends, I believe we must fight because our families, the families of our families, the children of our children are going to live in contamination. And as long as there’s suffering, there will always be a person who will step forward and stand up for everyone.

Joseph: Protest and struggle are very different, right? Protest is a specific moment, a specific event in the streets, in the city, for a cause. But struggle is something else. Struggle is a historical process that has a series of stages and a series of comings and goings. So they’re not just protesting. They’re fighting. And that difference, sometimes from the city, one doesn’t understand.

Silvia: We’ll take one last break and come back.

Eliezer: We’re back on El hilo.

Joseph: This is now, let’s say, the park now.

Holmer: Yes…

Eliezer: At the end of his journey through the Ecuadorian Amazon, on the way to the border with Peru, Joseph visited Yasuní National Park, Ecuador’s largest protected area.

Silvia: It covers an area of almost 10,000 square kilometers: that’s more than Buenos Aires, Santiago de Chile, Lima, São Paulo, Bogotá, La Paz, Mexico City, Caracas, and Quito combined.

Joseph: How many hectares did you tell me the park has?

Holmer: 1,022,376. If I’m not mistaken…

Joseph: And well, after spending a few days in Lago Agrio and learning about UDAPT’s struggle, one early morning I took a taxi that took me for an hour along the highway to the city of Coca, also called Francisco de Orellana, where there’s a port. And at that port, I took a fast boat that took me for about 5 hours or so downriver, along the Napo River, to the town of Nuevo Rocafuerte. There, Holmer came to pick me up in his boat to take me to meet his family in Yasuní Park.

I had the opportunity to spend a weekend in the Llanchama community with Holmer, a park ranger. He’s a young guy who has been living in that place for a long time. He’s a tour guide, but in recent years he’s worked as a ranger at Yasuní.

Holmer: In our cultures, we consider Yasuní National Park as one of our pharmacies, our market, our home, because in it we find everything. In one square meter there can be more than a thousand species, whether insects, plants, fungi.

Joseph: And entering Yasuní is impressive, it’s impressive, right? Because of the amount of stimuli you perceive—the songs of the birds, the monkeys, the trees, the air you breathe. That place is truly incredible.

Holmer: If at some point it were to be completely contaminated or destroyed, it’s like they’d be taking everything away from us, the cultures.

Joseph: It’s a place that has been considered one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. In fact, UNESCO in 1989 declared it a World Biosphere Reserve. It’s a very important place because of the number of fauna and flora species. But also because indigenous peoples live in that place—the Waorani live there, the Tagaeri. To this day, it has seen or has received pressure from the Ecuadorian State to exploit the oil in that place. Obviously with the consequences that generate. Among the operations, for example, of Petroecuador, which is that country’s state oil company, is Block 43, which operates in the park. That, of course, generates an impact not only in terms of possible water contamination but also noise. The noise too—the machines generate noise, sound pollution that affects the species living there. One thing I was able to find out from the data, from research, is that this oil exploitation is simply like a link in a much larger chain. In recent years, about 21 oil extraction blocks have been secured within Ecuador’s conservation areas. Which adds up, according to what I have noted here, to more than 7,000 square kilometers of territory in Ecuador. So in 2023, a popular referendum was held. Ecuadorian citizens voted in this referendum in favor of keeping Yasuní’s oil underground—that is, not exploiting it. With 58.9% of the total votes.

Holmer: For certain people, those of us who were fighting for the oil exploitation not to continue, well, it was a joy, but until now it’s not being fulfilled. The work of oil extraction within Yasuní National Park still continues.

Joseph: After that vote, the Constitutional Court gave the Ecuadorian government and Petroecuador a one-year deadline to close this Block 43 in Yasuní. To end the activities, to remove those installations that are there. But during that time, well, almost no progress has been made, right? In fact, a closure plan was submitted to the Constitutional Court. Not for one year, but for five years. The government said: Well, I’m going to close it in five years. But until now, according to the information I have, only 2% of the wells in Block 43 have been closed. In other words, only five wells out of 247 have been closed.

Eliezer: And is the fear that Yasuní could become another Lago Agrio?

Joseph: Of course. Of course. It’s an obvious fear that people living in that place have.

Holmer: If we don’t act now, if we don’t do something for conservation, well… This is going to become a desert over time, where most people will die from contamination.

Joseph: I remember something that a Cofán friend told me, a young Cofán guy who isn’t even 30 years old, named Andy Nixon. He’s like a leader, like an activist for the environment there in Lago Agrio. And he told me that before, that place—the Americans who came with Texaco named it Sour Lake, which is Lago Agrio, let’s say, because of the water extracted from those oil wells, which is salty, sour water. But what Andy Nixon told me was that the first Cofán, his ancestors, had already given that territory a name. It was called Amisacho. And amisacho in the Cofán language means place of guadas, which is a variety of enormous, thorny bamboo. So that place that used to be a place of guadas, entirely dedicated to conservation by these same indigenous peoples, became a Sour Lake, a sour lake, a devastated place contaminated by flares, by oil companies. I don’t know, when I think about Yasuní, I remember a lot of what my friend Andy told me: it could become that too. A sign that this could happen if we don’t do anything about it is this recent decision by the Ecuadorian government to merge the Ministry of Environment with the Ministry of Energy and Mines, so now the function of auditing or ensuring that companies respect environmental measures to protect the territory, the forest, the water, will no longer be in the hands of a separate institution, right? But will be in the hands of those who grant the concessions themselves. And that’s dangerous. That threatens a true exercise of justice for the populations living in that place. The thing is, there are still people, like these people I met in Ecuador, who are still fighting for this. And I believe it will be prevented from becoming a sour lake. It will be prevented and can be prevented. At least that’s the conviction I have. The population of Ecuador has risen up before. Indigenous peoples have risen up before, and they will rise up again if this doesn’t change. I’m sure of that.

Silvia: In the next episode…

Edgar Isuriza: We talked about 75 dredges; today we already have information that there are 120 dredges.

Marcelina Aguilar: You know what the dredgers are afraid of? That we organize as a community. The community has more strength.

Claudia Vega: What the miners don’t explain is that after they finish extracting the gold, the forest is contaminated, the water is contaminated, and the cost to the population’s health is very high.

Eliezer: This episode was produced by Silvia with reporting by Joseph and research by Rosa Chávez Yacila. It was edited by Daniel Alarcón. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design is by Elías González with music by Remy Lozano.

The rest of El hilo’s team includes Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask that you join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region, and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to learn more about today’s episode, subscribe to our email newsletter by going to elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it every Friday.

You can also follow us on our social media. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook, and Threads. You can find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share the episodes.

I’m Eliezer Budasoff. Thanks for listening.