Amazonía

Ecuador

COP30

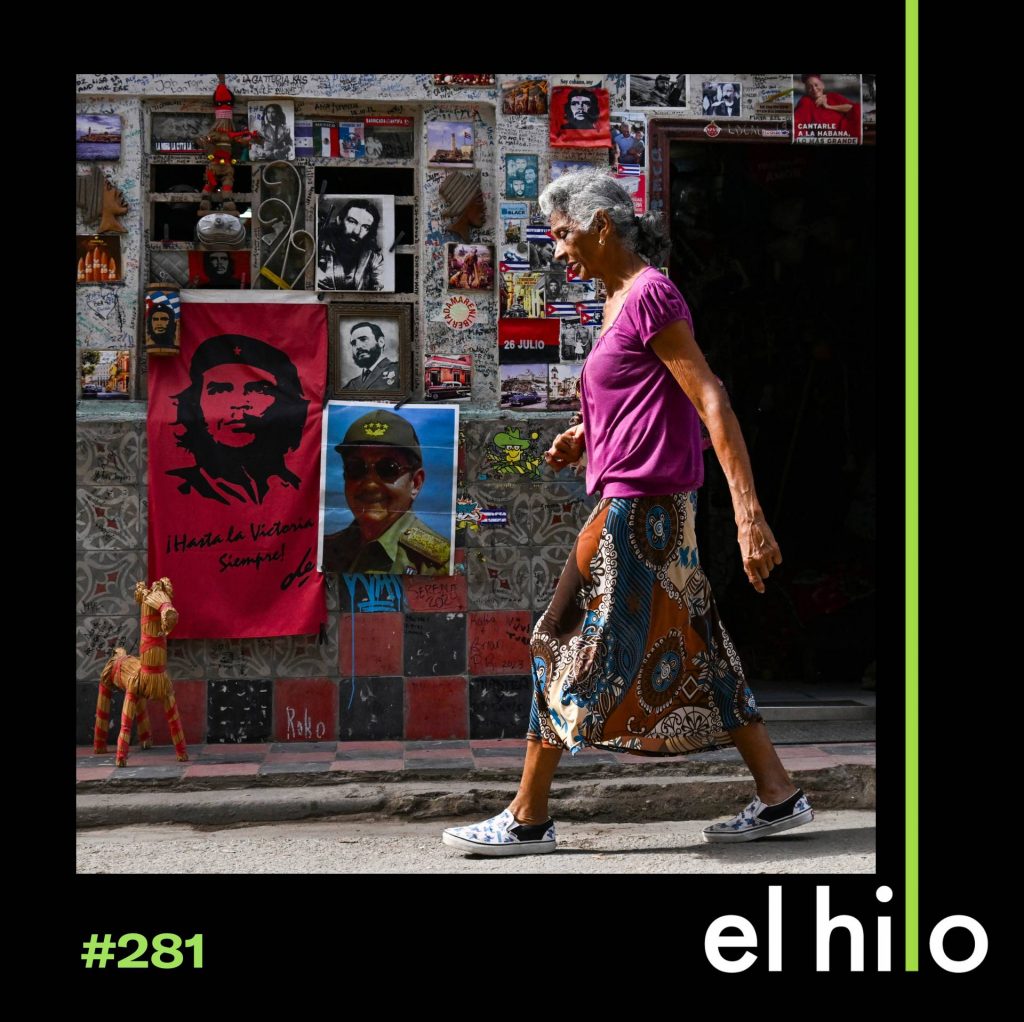

Yaku Churis

Guerreras por la Amazonía

Mecheros

Tena

Esta serie fue producida con el apoyo de Movilizatorio y Alianza Potencia Energética Latam.

En menos de un mes, líderes de todo el mundo se reunirán en Brasil para la COP30, un encuentro que ha prometido darles protagonismo a las comunidades de la Amazonía. Queríamos entender cómo las personas que habitan y cuidan el mayor bosque tropical del planeta se enfrentan y se adaptan al cambio climático y otros desafíos que se discutirán en esta conferencia. En cinco episodios de ‘Amazonas adentro’ vamos a acompañar al periodista peruano Joseph Zárate en un recorrido por cuatro países para escuchar cómo las experiencias y conocimientos de los pueblos amazónicos podrían transformar los enfoques de políticas climáticas, justicia y conservación. Empezamos en Ecuador, donde conocemos a los Yaku Churi, un grupo de niños que han generado una relación con el río a través del kayak, y aprenden a vigilarlo de la minería ilegal. También escuchamos a las Guerreras por la Amazonía, una organización de adolescentes que ganaron una demanda para que se eliminen los mecheros petroleros que están cerca de sus casas.

Créditos:

-

Reportería

Joseph Zárate -

Producción

Silvia Viñas -

Edición

Eliezer Budasoff, Daniel Alarcón -

Investigación

Rosa Chávez Yacila -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción digital

Natalia Sánchez Loayza, Helena Sarda, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Remy Lozano -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

Ilustración

Maira Reina

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Esta serie fue producida con el apoyo de Movilizatorio y Alianza Potencia Energética Latam.

Joseph Zárate: Qué lugar tan bonito, Yanda. Menos mal que lo han podido cuidar, porque…

Eliezer Budasoff: Están escuchando al periodista peruano Joseph Zárate. Está en Ecuador, en Puyo, la capital de la provincia de Pastaza, que queda en el nororiente del país, en el corazón de la Amazonía ecuatoriana.

Joseph: Estamos caminando por el bosque, yendo hacia el río Pastaza, que es un río grande, parece como un gran dios marrón.

Yanda: Sí, feliz viendo los árboles.

Joseph: Que son los que tú has plantado.

Yanda: Sí.

Silvia Viñas: Joseph estaba con Yanda Montahuano, un cineasta indígena sapara. Yanda tiene 35 años, una voz muy suave. Habla como si estuviera rezando. Y en el centro del pecho tiene un tatuaje que parece una flor, pero es el corte transversal de la planta de la ayahuasca, que es como una liana o soga.

Joseph: Yanda ha dedicado los últimos años de su vida a profundizar en el uso de la ayahuasca, del remedio como él le llama. De la medicina.

Yanda: Estamos cruzando el río. Joseph viene atrás. Estamos yendo al Pastaza a tabaquear.

Joseph: El río Pastaza nace en las faldas de un volcán que se llama Tungurahua y que llega hasta el Perú, hasta Loreto. Y ahí se une con el río Marañón, y el Marañón, a su vez, se une al río Amazonas. Digamos, es un río muy importante, que los pueblos originarios que viven en esa zona de la Amazonía han recorrido durante generaciones. Y estamos caminando porque Yanda siempre me aconsejó que para tomar ayahuasca es importante que el bosque nos reconozca, que el bosque pueda de alguna manera abrirnos las puertas de ese espacio. Es como cuando llegas a una casa y pides permiso. Hemos también aspirado tabaco. El tabaco es muy importante también, antes de la ceremonia de ayahuasca, porque también despeja cualquier neblina mental. Es como un purificador, me decía Yanda. Y estuvimos caminando más o menos como unos 40 minutos, hablando de todo, ¿no? De la vida en el bosque, de los proyectos de Yanda, de los sueños de Yanda, de la importancia de los sueños para el pueblo al cual pertenece él.

Yanda: Los sueños son muy importantes para nuestra existencia, para nuestro… De hoy, para el mañana, para ver qué sucede en nuestras vidas o en nuestra aldea…

Joseph: Él me explicaba que los sueños les advierten de ciertas enfermedades, de ciertos sucesos. Les ayudan a interpretar circunstancias específicas de lo que están viviendo, ¿no? Y eso me hacía mucho sentido. O sea, durante generaciones los pueblos originarios han utilizado, o creen que los sueños, y en realidad los mitos también, las historias, son como máquinas narrativas sofisticadas para poder interpretar el mundo.

Yanda: Por ejemplo, la misma COP, a donde vas, yo tuve un sueño sobre ellos

Joseph: Me interesaba mucho su opinión sobre lo que hoy en día está viviendo la Amazonía. Y le hablé específicamente de la COP, de la COP30 que se va a realizar en noviembre en Belém do Pará, en el Brasil, ¿no? Que es en la desembocadura del Amazonas. Y él me contaba que él ya había asistido a varias otras COP. Yo nunca he ido a una COP, no sé más o menos cómo es. Y me comenzaba a contar que él sentía que, pues, estas cumbres del clima han servido para muy poco en realidad. Y él me explicó eso a través de un sueño que él tuvo.

Yanda: La COP era como un tren donde mucha gente va, se sientan y están ahí. Y ese tren está muy lleno. Y yo también entré ahí y luego fui a ver quién conducía…

Joseph: Entonces caminó hacia la locomotora o hacia la parte de adelante del tren, en busca del conductor, y cuando llegó a la cabina, no encontró a nadie.

Yanda: Ese tren iba al vacío así. A neblinas. No había un camino. Entonces siempre creo que este evento súper grande no es la solución.

Joseph: Para él, estas cumbres un poco son eso, ¿no? Como un gran armatoste lleno de gente, lleno de voluntad, de ideas, pero que no tiene una dirección. Es un tren hacia la nada.

Eliezer: Joseph va camino a esa próxima COP, y nosotros vamos a acompañarlo. Empezó su recorrido en Ecuador, aquí, con Yanda. Esta semana, en dos episodios, nos va a llevar por dos puntos clave para entender la amazonía ecuatoriana.

Silvia: Luego vamos a ir a Perú, Colombia y Brasil, hasta Belém do Pará, donde en noviembre se van a juntar los líderes del mundo para buscar soluciones a la crisis climática. Soluciones que, para Yanda, están en otro lado.

Yanda: Creo que las respuestas frente a todos los desastres grandes que vivimos están en los bosques. Está en la medicina, está en culturas que están proponiendo las posibilidades de otras formas de vivir, no esas posibilidades de vivir destruyendo como: “hay que invertir en temas de explotación petrolera, minería y otros”. Eso debería ya estar pasando a otro plano en estos tiempos, pero no lo estamos logrando. Y eso es un trabajo de todos también.

Eliezer: Esto es Amazonas adentro, una serie de El hilo, de Radio Ambulante Studios. Episodio 1: Los niños del agua y las niñas guerreras.

Joseph, nota de voz: Son casi las cinco de la tarde y estoy sentado sobre un tronco a orillas del río Pastaza, que es un río muy grande…

Eliezer: Esa tarde, cuando estabas en el río Pastaza, tú grabaste una nota de voz que nos mandaste.

Joseph, nota de voz: Y hemos hecho una parada para poder inhalar un poco de tabaco líquido.

Eliezer: Suenas un poco melancólico en esa nota de voz. ¿Cómo te estabas sintiendo?

Joseph: Bueno, yo siempre estoy melancólico, ¿no? Es mi manera de ser, digamos. Pero yo creo que en particular en ese momento fue, un poco el efecto del tabaco también y de la conversación, que era una conversación muy profunda. Pero también porque pensaba mucho en cómo capturar todo lo que yo iba escuchando, viendo, de este viaje.

Joseph, nota de voz: Mi mente no ha dejado de pensar todo el tiempo en cómo me va a ir en este viaje.

Joseph: Porque claro, querer contar el río, querer contar el bosque es una empresa imposible, porque ahí son muchos estímulos, son muchas cosas que están ocurriendo a la vez.

Joseph, nota de voz: Intentar contar una historia coherente, una historia que pueda interesar, que pueda expresar lo que yo estoy viviendo y viendo aquí.

Joseph: Y es como entrar al río con humildad, ¿no? O sea, hubo mucha otra gente que quiso contar el río antes que yo, y después de mí habrá mucha otra gente más. Soy solamente una persona limitada que va a intentar capturar una parte de la experiencia de recorrer el río Amazonas. Y lo otro era sin duda el pensar, también, en la gente que uno va perdiendo. Mi padre falleció apenas hace un año. Pensaba mucho en él. Pensaba mucho en mi abuela también.

Joseph, nota de voz: Yo mismo soy en parte amazónico por mi abuela, pero a veces siento que esa conexión se ha perdido en algún punto de la historia.

Joseph: Falleció ya hace algunos años también, que era una mujer que nació en una comunidad indígena en la Amazonía del Perú.

Joseph, nota de voz: En que tal vez me puedan estar acompañando en este viaje también. Que viajen conmigo, ¿no? O eso quiero creer también.

Joseph: Pensaba en por qué estaba ahí. O sea, ¿qué rayos estoy haciendo acá? O sea, ¿por qué hay algo en mi que durante los últimos, no sé, la última década me ha ido arrojando a ir a la Amazonía? Yo estoy convencido de que todas las personas resonamos con una geografía específica. O sea, hay personas que resuenan con los océanos, otras que resuenan con el desierto. En mi caso, creo que debido a vivir en la casa de mi abuela amazónica es que yo resueno con la selva, a pesar de que soy una persona de la ciudad, ¿no?

Joseph, nota de voz: Lo cierto es que tengo un poco de temor. Un poco de ansiedad también por saber cómo hacer este trabajo.

Joseph: Pero cuando tomé la ayahuasca, por ejemplo, fue esa noche, tomé con Yanda y yo obviamente me había preparado, me bañé en el río, ¿no? estábamos solamente él y yo. Yo estaba echado sobre el piso de la cabaña y de pronto comencé, estando despierto, comencé a percibir los sonidos de la selva de una manera como jamás yo había sentido. Comencé a sentir sonidos muy finos. No solamente los insectos, las aves, algún animal rastrero, el sonido del río, pero todo a la vez. Como si fuera una gran sinfonía, no sé, de la naturaleza. Pero con una nitidez tan, tan, pero tan grande que yo sentí que era como una especie de mensaje. De decir: “Ah, bueno, de repente, lo único que tengo que hacer yo es escuchar”. Escuchar. Estar atento a los sonidos, a lo que la gente me tiene para decir, hablar menos, pensar menos y escuchar.

Joseph: Después del río Pastaza fui hasta una ciudad que se llama Tena, una localidad que está a más o menos una hora y media en auto desde Puyo. Y fui en la camioneta de un amigo que se llama Darwin. Un quiteño, músico. Un artista de música latinoamericana que toca la zampoña, la quena. En verdad un gran artista. Y fuimos en su auto escuchando música, las grabaciones que él ha hecho. Fue muy divertido ese viaje.

Bueno, Tena es una ciudad muy particular. Cuando uno llega a la ciudad, a la entrada de la ciudad, uno puede ver como una especie de arco de bienvenida. Y en la esquina de ese arco hay como un gran, una gran escultura de un hombre en un kayak. Entonces ya solamente ver eso ya te da una idea de cuál es la actividad principal de ese lugar, ¿no? Es decir, es una ciudad a donde van muchos turistas a hacer kayak en los ríos. Pero a la vez también, así como hay esta práctica deportiva en el río Jatunyacu, también hay una actividad económica muy fuerte vinculada a la minería de oro. Estamos hablando de minería artesanal, hecha muchas veces sin licencia. Y en otras ocasiones hecha con licencia, con permisos, pero a pesar de eso incumplen las normas ambientales, generando por supuesto un impacto muy grave en el ecosistema, en el río, en el bosque, y en la gente que vive cerca a estos territorios.

Líder de taller: Pueden escribir una carta, puede ser una reflexión para… O un dibujo.

Joseph: Y yo estaba yéndome para ahí porque iba a asistir a una serie de talleres que estaba dando un grupo de Amnistía Internacional a niños y jovencitas activistas.

Líder de taller: Sobre la siguiente pregunta: ¿cuál fue el cambio más significativo en tu vida por haber participado del colectivo Guerreras por la Amazonía?

Joseph: Un grupo de ellos, los niños, pertenecen a un grupo que se llama Yaku Churi. Que Yaku es agua y Churi es niño en kichwa. Y estos niños se dedican pues a hacer kayak ¿verdad? A practicar el kayak en el río Jatunyacu, que es un río importante del Tena, y en la práctica de ese deporte generan una conciencia, una relación con el río, la importancia de cuidarlo, de vigilar, por ejemplo, que no se haga minería en esa zona. Y por otro lado está el grupo Guerreras por la Amazonía, que es un grupo de niñas y adolescentes que viven en Sucumbíos, que es una provincia donde hay mucha explotación de petróleo. Y que ellas hacen un activismo para poder defender sus territorios de esa contaminación causada por el petróleo y por los mecheros de gas. Entonces, era un encuentro de estos dos grupos que iban a recibir una serie de charlas, de talleres de incidencia ─como le llaman─, de desarrollar estrategias comunicacionales para que las autoridades, los tomadores de decisiones, puedan de alguna manera hacer algo para poder proteger los territorios, los bosques y el lugar donde ellos viven.

Silvia: Ya. ¿Y pudiste hablar con algunos de estos chicos y chicas?

Joseph: Sí, por supuesto. Yo traté en lo posible de no interrumpir demasiado el taller, pero sí pude hablar con ellos.

Leonela Moncayo: Bueno, pues me presento, mi nombre es Leonela Moncayo, tengo 15 años de edad, soy de la provincia de Sucumbíos y ahora en la actualidad soy guerrera por la Amazonía

Joseph: Leonela Moncayo es una activista de derechos humanos. Bueno, todavía está en la escuela. Y fue increíble conocerla porque en verdad no parecía de 15 años. Me pareció una persona mayor.

Leonela: Nuestro trabajo es pelear en contra de los mecheros que, pues, al momento que extraen el petróleo del subsuelo no reutilizan ese gas, sino que lo que hacen es botarlo al aire libre, utilizándolo de forma irresponsable quemando estos mecheros.

Joseph: Los mecheros son enormes estructuras metálicas. Son como largas tuberías que se proyectan desde la tierra hacia el cielo, y que si uno las ve a la distancia, parecen enormes antorchas olímpicas. Pero en realidad son parte de un sistema industrial de quema de gas natural, que funciona a una temperatura promedio de unos 400 grados centígrados. Es muchísimo calor. Y que en ese proceso también libera gases que son muy tóxicos para la salud de las personas que viven en ese territorio.

Leonela: Yo he tenido cerca los mecheros, un mechero que estaba cerca de mi casa, que estaba al frente de mi casa. Yo podía verlo todas las noches, lo escuchaba todos los días. La pestilencia que expulsaba este mechero todos los días era terrible. La calor cuando hacía los días de calor era peor, porque esa pestilencia llegaba peor cuando eran los días de calor así.

Joseph: Entonces ella me contaba, por ejemplo, que cuando ella tenía nueve años fue que ella empezó, digamos, en este trabajo, en esta actividad de defender el territorio y que a lo largo de todo este tiempo ella ha visto cómo ha ido afectando los mecheros y la afectación petrolera, no en otra gente, sino en su propia familia.

Leonela: Hasta la actualidad el lugar ya no es muy bueno como para la agricultura o para cultivar sembríos. Mi familia tiene cacao, pero el cacao ya no da tanto como lo daba antes. En mi comunidad tampoco, no tenemos agua potable. Nosotros utilizamos agua de lluvia, que es lo peor, y es lo único que nos queda, sin embargo.

Joseph: En las provincias de Sucumbíos y Orellana hay registros del incremento de casos de cáncer. En 2021, por ejemplo, la UDAPT documentaba 251 casos de cáncer. Pero luego para el 2024 la cifra de personas con cáncer subió a 531 casos. Del total de todas estas personas, un 73% son mujeres. Entonces cuando hablé con Leonela, ella me contaba que también tiene familiares enfermos de cáncer. De hecho, su casa queda muy cerca de un mechero, de estas tuberías que parecen grandes antorchas olímpicas.

Leonela: Siempre tengo problemas en la piel. Yo, mi familia. He tenido también familia que ha sufrido de tumores internos, en los senos…

Joseph: Y debido al activismo que ella ha ido haciendo, y al ser tan vocal, digamos, frente a estas injusticias, ella me contaba que ha sido incluso afectada por algún tipo de amenaza, o algún tipo de atentado.

Leonela: A nosotras nos han intentado callar. Yo tuve un atentado en mi casa, han retenido los buses en el que siempre viajamos para Quito, no permiten que hagamos marcha.

Joseph: Que han tirado explosivos en la esquina de su barrio cuando ella, justo unos días antes, había dado alguna declaración pública, ¿no? Respecto a eso. Entonces lo que ellas están haciendo no es algo, no es algo menor. ¿no?

Ellas lograron que la Corte Provincial de Justicia de Sucumbíos fallara a favor de la demanda que ellas presentaron, que es una demanda para que se eliminen los mecheros aledaños a las comunidades y centros poblados. En 2021 la Corte Provincial falló a favor de esta demanda para que, hacia el 2023, estos mecheros desaparezcan. Entonces, en el momento de la sentencia, por ejemplo, en ese momento habían 447 mecheros, pero ahora hay 39 mecheros más, es decir, hay 486, que están en la selva del Napo, Sucumbíos y Orellana, que son las provincias que están al norte de la selva del Ecuador. Entonces, claro, no solamente no han cumplido con hacer efectivo la sentencia, sino que han aumentado los mecheros. Entonces en agosto de este año, estas niñas han presentado una acción de incumplimiento contra el Estado ecuatoriano ante la Corte Constitucional. Entonces están exigiendo que la sentencia se cumpla. Pero no ha pasado, más bien hace unos meses, en julio nomás, el presidente de Ecuador, Daniel Noboa, ha ordenado que se fusione el Ministerio del Ambiente con el Ministerio de Energía y Minas, ¿no? Es decir que ahora todas las funciones que cumplía el Ministerio de Ambiente en fiscalizar, en cuidar que no haya atropellos medioambientales por las industrias, ahora esa labor la va a hacer el Ministerio de Energía y Minas. Es decir, hay juez y parte, ¿no? Entonces, claramente el gobierno actual de Ecuador tiene una línea de trabajo, o de hacer, digamos, de no cumplir este tipo de sentencias que ayudan a que el impacto de la crisis climática sea menor. Al contrario, ¿no? Entonces, de nuevo, es como volver a este sueño de Yanda, de que es un tren que no tiene un destino, que no tiene como un liderazgo visible de poder cambiar las cosas.

Eliezer: Una pausa y volvemos.

Silvia: Queremos contarles que el jueves que viene, 23 de octubre, vuelve Central, el canal de series de Radio Ambulante Studios, con una historia que nos impactó desde el primer momento: una tragedia inquietante, privada, que terminó poniendo en foco la mayor trama de sobornos del continente.

Eliezer: La Ruta del Sol reconstruye un caso que sacudió a todo un país, y cuenta la historia de una familia y un puñado de personas quedaron atrapadas en esa frontera borrosa donde se cruzan el poder económico, el poder político y la corrupción. La pueden escuchar a partir del jueves que viene en central podcast punto audio, o en cualquier aplicación de audio. Acá les dejamos un pequeño adelanto:

David Trujillo: A finales de 2018, una tragedia familiar estalló un escándalo en Colombia… Vamos a reconstruir el impactante caso de la muerte de Jorge Enrique Pizano, uno de los principales testigos del caso Odebrecht, y tres días después la de su hijo, Alejandro.

Juanita: Inmediatamente le pregunté: ¿Quién mató a mi papá? ¿Quién fue? ¿Quién estaba ahí?

David Trujillo: La historia de dos muertes, una botella de agua envenenada y una red de corrupción internacional. Escucha en Central La ruta del sol en la app de iHeartRadio, Apple Podcasts, o donde sea que escuches tus podcasts.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta.

Joseph: ¿Y qué se puede ver cuando uno pasa por ahí, por ejemplo, cuando tú pasas con el kayak?

Jair: Antes, cuando pasábamos con el kayak era solo verde. Veíamos a un lado al otro, y era solo verde.

Eliezer: Antes de la pausa conocimos a Leonela, una de las chicas de Guerreras por la Amazonía que estaba participando en un taller con los chicos de Yaku Churi. Joseph también habló con ellos.

Jair: En estos momentos, como han entrado los mineros, vas, ves un poco verde, después ves montañas de piedras, máquinas, piedras cambiadas de colores, el río sucio. Como la minería lava el oro, bota toda el agua al río.

Joseph: Tuve la oportunidad de hablar con uno de los niños, que se llama Jair, cuya familia, algunos familiares trabajan en la minería en esa zona.

Jair: Antes era súper lindo escuchar los sonidos de la naturaleza. Era súper lindo. Ahora solo escuchas las máquinas cómo están destruyendo, cómo talan los árboles. Y es feo, la verdad.

Joseph: O sea, uno pasa y puede ver claramente eso.

Jair: Sí, claramente. Están al ladito del río.

Joseph: Y Jair me hablaba pues de cómo la contaminación por la minería y la presencia del uso del mercurio, que es un metal tóxico, va afectando, va contaminando, no solamente la calidad del agua, sino también la calidad de los peces que ellos consumen.

Jair: Hay peces que se están mutando, y se mueren.

Joseph: Afectando un poco también el turismo en ese lugar, porque al hacer minería van destruyendo también el ecosistema y el lugar donde el río… por donde el río pasa ¿no? Entonces, un chico muy lúcido, y que tenía como muy claras las cosas.

Jair: El mercurio da mutaciones, entonces es feísimo como contaminan. Las personas que viven del río ya no pueden tomarla. No pueden. Ya no pueden. El río está muriendo.

Silvia: Bueno, como tú decías, estos niños suenan mayores de lo que son. ¿No? Leonela tiene 15, Jair 14. Y suenan como muy preparados para hablar sobre estos temas tan complejos. Así que nos gustaría entender mejor qué hay detrás de todo esto, de la formación de estos chicos. Entonces, cuéntanos sobre los adultos que estaban organizando estos talleres? Quién está detrás de Yaku Churi, por ejemplo.

Joseph: Bueno, de parte de los Yaku Churi, de estos niños del agua, digamos, el fundador de esta asociación es Diego Robles. Que también es un joven. Diego tiene apenas 35 años, también. Y él es un experto en kayak.

Diego Robles: No debo excluir que también me dedico a la actividad de turismo y a la ebanistería. Son como mis fuertes. Pero todo esto siempre va en conjunto.

Joseph: Y él nació en Sucumbíos. Es decir, él nació en la provincia de donde son las niñas o las Guerreras por la Amazonía, de esa misma zona, de un pueblo específico que se llama Shushufindi. Es un pueblo donde hay también plantas petroleras, hay también mecheros. Y Diego me contaba que toda esta idea de trabajar en favor de la naturaleza y en favor de reducir el impacto de las industrias, de oponerse, digamos, a la extracción minera o a la extracción petrolera en la selva del Ecuador, empezó porque su madre murió de una extraña enfermedad, posiblemente de cáncer, debido a la cercanía que tenía su casa con uno de estos mecheros, que liberan gases tóxicos y que afectan la salud de la gente.

Diego: Ella vivía a 100 metros de un mechero de petróleo. A 100 metros, donde queman los gases del petróleo, y se contaminó. Y yo no había ni nacido. Te hablo del año 85, por ahí cuando estaba el boom petrolero. Texaco, para ese entonces.

Joseph: Entonces, cuando él se muda hacia el Tena para poder trabajar, de nuevo en esta industria turística, del kayak y demás, él dijo: “Pues bueno, no solamente quiero ser un guía turístico, sino que quiero hacer algo para poder proteger este río donde yo practico mi trabajo, practico mi deporte”.

Diego: Ver acá lo que está pasando, empezó a pasar con el tema del río, minería, destrucción, claro, ahí es donde viene toda la conexión. Mi madre física desapareció. ¿Pero cuál es la verdadera madre? La que nos sostiene. La tierra, el agua. La vida. Nos da de comer. Nos sostiene. Cada pozo petrolero, cada excavadora cavando, es como que le estén perforando el pulmón a tu mamá. Esa es la cosa. Estamos matando a nuestra madre. No es solo una cosa, es un ser vivo. Es nuestra mamá. Entonces para mí se me vino a la cabeza muy fuerte esta conexión, esto que está pasando, esto que pasó con mi madre, a lo que pasa ahora con nuestra Amazonía, con nuestro planeta en general.

Al empezar a ver el río sufrir, ahí fue cuando decidí transformar el deporte.

Joseph: Diego decide practicar su trabajo y su deporte de una manera mucho más integral. No solamente va a ser mi medio de trabajo, sino también va a ser un propósito para cumplir, cuidar el río. Entonces, a través de la enseñanza del kayak y de hacer turismo en el kayak, Diego Robles le enseña a estos niños a cuidar el río, la importancia de cuidar el río, de vigilarlo, la posibilidad de practicar, de ganarse la vida haciendo un turismo sostenible a través de ese deporte.

Diego: Y chuta, cuando vi a estos niños en el río Jatunyacu, ahí vuelves a tu niñez. Algo con los Yaku Churis es que yo fui uno de ellos. O soy uno de ellos. Sin apoyo, apoyo económico. Sin una persona que te empuje. Y me di cuenta que tenían mucho talento para el río. Pero no había una educación. O sea, tienen talento, son hábiles. Ellos trabajan la tierra, todo. Pero no había una educación.

Eliezer: Hace un rato escuchamos un poco a Jair sobre lo que él ve cuando está en el kayak. ¿Pero qué te contó Diego sobre estos chicos? ¿En qué situaciones viven y cómo les ayuda el kayak?

Joseph: Bueno, muchos de estos niños ─porque la mayoría de estos son preadolescentes, digamos, tienen, no sé, 10 años, 11 años, 12 años, ¿no?─. Y estos chicos, pues, viven en familias de escasos recursos económicos.

Diego: Tienen historias muy duras. Principalmente, la mayor parte de padres tienen problemas de alcoholismo, violencia intrafamiliar. Y el caso más duro es el del Tupac, que él ya estaba acercándose a las pandillas en Tena.

Joseph: Sus hermanos habían sido asesinados por pandilleros relacionados al narcotráfico. Uno de sus familiares había trabajado también en la minería ilegal de oro.

Diego: Entonces es el caso más fuerte. Y es uno de los que más se ha desarrollado, la parte interesante. Buscó transformarse y ahora está sostenido ahí. Él en su vida quiere ser kayakero y ser profesional en eso.

Joseph: A veces, debido a la ausencia del Estado ─ecuatoriano en este caso─, y a la ausencia de posibilidades de otros futuros posibles, ellos se ven arrojados a ese tipo de economías. Porque no hay otra manera de repente de ganar dinero, poder progresar. Entonces se ven presionados en esa dirección. Entonces, lo que hace Yaku Churi a través del kayak es mostrarles otra posibilidad de futuro. Es decir, Oye, no tienes por qué elegir ese camino. Puedes elegir otros.

Diego: Yo creo que no hay mejor escuela que el río. Sí, porque el río fluye y tú tienes que aprender a fluir con el río. ¿Entiendes? Es igual que en la vida, es como manejarse así, enfrentar problemas, situaciones, saber cómo enfrentarla, saber cuándo poder caminar el rápido. O me atrevo a este rápido, pero sé que el rápido me va a dar a veces una revolcada. Lo principal que enseña es fortaleza, fortaleza mental.

Joseph: El kayak les da una herramienta de trabajo. De hecho, muchos de ellos han decidido practicar ese deporte. Participan en competiciones. Y es increíble cómo ellos practican el deporte y cómo eso también le da una seguridad, ¿no? De poder hacer algo muy diferente a lo que probablemente la pobreza les arroja a hacer.

Silvia: ¿Y qué crees que quería lograr Diego al juntar a los Yaku Churi con las Guerreras por la Amazonía? ¿y como se conecta quizás a su mamá no? Porque nos decías que las guerreras son del mismo sitio que era su mamá.

Joseph: Sí, totalmente. Bueno, Diego es un joven apasionado. Muy sensible ¿no?. Y él me decía que cuando él veía y escuchaba hablar a estas jovencitas con tanta seguridad, con tanta valentía, él recordaba a su madre.

Diego: A veces ya, creo que en el taller unas veces se me iban las lágrimas. Ya no podía. O sea, aguanté por, no sé, por valentía, digamos. No… No mostrar a los niños eso. Pero claro, ver unas niñas luchando por algo que mi mamá murió….

Joseph: Él recordaba a su madre, y recordaba por qué él estaba haciendo lo que estaba haciendo ahora, ¿no? De proteger el río, defender el río. Y para él, como fundador de Yaku Churi, era muy importante que sus niños, que los niños Yaku Churi se contagien de ese empoderamiento, se contagien de esa valentía, de esa elocuencia a la hora de hablar y de defender sus derechos.

Diego: Este taller es prácticamente para que ellos entiendan la realidad de lo que ellos son parte, Porque a veces, como que piensan que solo es el kayak, la carpintería, pero para que entiendan la realidad de su voz como defensores del territorio.

Joseph: Diego quería que los Yaku Churi se contagien de eso, ¿no? Y puedan también aprender herramientas a través del ejemplo. Ah, mira, esas niñas tienen tu misma edad, y hablan con valentía y no tienen miedo de decir lo que piensan, etcétera. Entonces, yo creo que ese espacio fue creado para poder compartir esas experiencias, mientras que las niñas, las Guerreras por la Amazonía, les enseñaban con el ejemplo de este, de su discurso, de su manera de ser y demás, los Yaku Churi les enseñaban un poquito sobre el río, ¿no? Sobre cómo conducirse en el río. Hubo un momento en que todos fuimos al río a hacer kayak, a hacer rafting por el Jatunyacu. Y yo creo que ese fue un momento muy, muy bonito de compartir entre ambos grupos.

Eliezer: Después de la pausa Joseph va con las Guerreras por la Amazonía y los Yaku Churi a navegar por el río Jatunyacu. Ya volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Diego: El río va a ser un poco más rápido de lo normal, igual está muy divertido. Hay unas olas buenas, grandes, súper chévere.

Eliezer: ¿Cómo fue ese día de recorrer en kayak junto a estos chicos?

Joseph: Bueno, fue muy emocionante, ¿no? yo nunca había hecho este deporte en ningún río. De hecho, yo no sé nadar. No sé nadar. Entonces, me acuerdo que fuimos todos en un bus.

Éramos un grupo grande, ¿no? Yo te diría pues… ¿cuántas personas? Por lo menos más de 30 personas. Estaban los niños de de Yaku Churi, estaban las Guerreras por la Amazonía.

Había unos guías también que iban a conducir cada uno de los botes donde se hace rafting. Que es como, se hace como una especie de botes de inflable, ¿no? Donde van seis personas. Y los kayak, que son estos botecitos individuales. Entonces en los kayak Individuales iban los Yaku Churi, ¿no? Que son los que saben hacer ese deporte. Y en los botes inflables grandes íbamos los que no sabíamos hacer ese deporte. Cada uno con un guía, ¿no?

Joseph: Seguimos remando… Creo que hemos chocado contra una piedra.

Diego: ¡Alto!

Joseph: Entonces estábamos todos bajando por el Jatunyacu rumbo al Napo, porque Jatunyacu se junta con otro río y forman el río Napo. Entonces estábamos yendo hacia allí. Fue un viaje más o menos… Porque hicimos algunas paradas, ¿no? Estamos hablando de una hora y media más o menos. Y a lo largo de ese viaje, que fue muy emocionante porque había momentos donde había un rápido y había rocas y había olas que se iban formando. Y de pronto nos mojamos todos la ropa. Yo tenía la grabadora puesta ahí, en un espacio en mi chaleco salvavidas. Y trataba de seguir las instrucciones de Diego, que estaba en mi bote, pero yo no sabía cómo remar, y lo único que podía hacer era, digamos, no sé, tratar de ir para adelante.

Diego: Mira todo esto es minería, mira. Todo al frente es minería. Todas esas piedras.

Joseph: Y yo iba conversando con Diego sobre lo que íbamos viendo, ¿no? Y mientras íbamos cruzando en el río, Diego me iba describiendo lo que lo que veíamos y lo que veíamos era montículos de tierra a las orillas del río Jatunyacu y algunos tractores, ¿verdad? La presencia de… Como de tierra removida, como si hubiera sido apenas, digamos, revuelta o remecida por las máquinas, ¿no? Y ahí estaba pues, la presencia de la minería.

Diego: La minería, como tú mismo puedes presenciar, está destruyendo totalmente las cuencas del río y eso también es una afectación, porque esto influye a que haya deslaves, a que el río pierda su cauce. Pero también, bueno, algo que a mí me impacta también, es ver cómo la naturaleza ha tomado la decisión de limpiarse. Por ejemplo, ahí vi al menos dos puntos mineros que han sido inundados y están ahora prácticamente tapados los huecos de la minería. El río está reclamando su espacio, su territorio. Es increíble.

Joseph: ¿Vamos a parar acá, verdad?

Joseph: Hacíamos paradas y subíamos a la colina para ver un poquito más hacia adentro y veíamos, pues, la devastación. Había hectáreas de bosque deforestado. Una especie de pozas marrones donde hubo en ese, en algún momento, la explotación de mineral. Veíamos también especies de cabañas que se habían construido. En ese momento no había nadie. Pero podíamos ver, digamos, los efectos de la minería en ciertas partes de la cuenca del Jatunyacu.

Joseph: Totalmente empapado.

Joseph: Bueno, al final recorrimos esa hora y media del río, no pasó nada. No me caí al río, menos mal. Pero fue muy emocionante haber hecho ese viaje.

Joseph: ¿Qué tal? ¿Qué tal la recorrida?

Chicas: Bien, muy bien, bonito. Excelente.

Joseph: ¿Alguien se ahogó?

Chica: No, pero hay que experimentar…

Silvia: En el próximo episodio…

Wilmer Lucitante: Para las empresas petroleras somos una piedra en el zapato porque decimos la verdad.

Frank Jurado: Estamos en un sector muy rico, donde hay petróleo, la explotación. ¿Pero de qué nos sirve a nosotros si nosotros vivimos en la miseria?

Jamileth Jurado: Hasta el último momento que se acabe la contaminación, yo creo que nosotras debemos luchar, porque nuestras familias van a vivir en contaminación.

Pablo Fajardo: Y lo hacemos porque digo: “al menos cómplice de esos crímenes no quiero ser y no voy a ser”.

Eliezer: Este episodio lo produjo Silvia con la reportería de Joseph y la investigación de Rosa Chávez Yacila. Lo editamos Daniel Alarcón y yo. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido es de Elías González con música de Remy Lozano.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Soy Eliezer Budasoff. Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

This series was produced with the support of Movilizatorio and Alianza Potencia Energética Latam

Joseph Zárate: What a beautiful place, Yanda. Thank goodness you’ve been able to take care of it, because…

Eliezer Budasoff: You’re listening to Peruvian journalist Joseph Zárate. He’s in Ecuador, in Puyo, the capital of Pastaza province, located in the northeastern part of the country, in the heart of the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Joseph: We’re walking through the forest, heading toward the Pastaza River, which is a large river, it looks like a great brown god.

Yanda: Yes, happy to see the trees.

Joseph: The ones you’ve planted.

Yanda: Yes.

Silvia Viñas: Joseph was with Yanda Montahuano, an indigenous Sapara filmmaker. Yanda is 35 years old, has a very soft voice. He speaks as if he were praying. And in the center of his chest he has a tattoo that looks like a flower, but it’s the cross-section of the ayahuasca plant, which is like a vine or rope.

Joseph: Yanda has dedicated the last years of his life to deepening his use of ayahuasca, the remedy as he calls it. The medicine.

Yanda: We’re crossing the river. Joseph is coming behind. We’re going to the Pastaza to use tobacco.

Joseph: The Pastaza River is born on the slopes of a volcano called Tungurahua and reaches Peru, all the way to Loreto. And there it joins the Marañón River, and the Marañón, in turn, joins the Amazon River. Let’s say, it’s a very important river that the indigenous peoples who live in that area of the Amazon have traveled for generations. And we’re walking because Yanda always advised me that to take ayahuasca it’s important that the forest recognizes us, that the forest can somehow open the doors of that space for us. It’s like when you arrive at a house and ask for permission. We also inhaled tobacco. Tobacco is also very important before the ayahuasca ceremony, because it also clears any mental fog. It’s like a purifier, Yanda told me. And we were walking for about 40 minutes, talking about everything, right? About life in the forest, about Yanda’s projects, about Yanda’s dreams, about the importance of dreams for the people he belongs to.

Yanda: Dreams are very important for our existence, for our… For today, for tomorrow, to see what happens in our lives or in our village…

Joseph: He explained to me that dreams warn them of certain illnesses, of certain events. They help them interpret specific circumstances of what they’re experiencing, right? And that made a lot of sense to me. I mean, for generations indigenous peoples have used, or believe that dreams, and actually myths too, stories, are like sophisticated narrative machines to be able to interpret the world.

Yanda: For example, the COP itself, where you’re going, I had a dream about them.

Joseph: I was very interested in his opinion about what the Amazon is experiencing today. And I specifically talked to him about the COP, about COP30 that will be held in November in Belém do Pará, in Brazil, right? Which is at the mouth of the Amazon. And he told me that he had already attended several other COPs. I’ve never been to a COP, I don’t really know what it’s like. And he started telling me that he felt that, well, these climate summits have served very little in reality. And he explained that to me through a dream he had.

Yanda: The COP was like a train where many people go, they sit and they’re there. And that train is very full. And I also got in there and then I went to see who was driving…

Joseph: So he walked toward the locomotive or toward the front of the train, looking for the conductor, and when he got to the cabin, he found no one.

Yanda: That train was going into the void like that. Into mist. There was no path. So I always believe that this super big event is not the solution.

Joseph: For him, these summits are a bit like that, right? Like a big apparatus full of people, full of willingness, of ideas, but that has no direction. It’s a train to nowhere.

Eliezer: Joseph is on his way to that next COP, and we’re going to accompany him. He started his journey in Ecuador, here, with Yanda. This week, in two episodes, he’s going to take us through two key points to understand the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Silvia: Then we’re going to go to Peru, Colombia, and Brazil, all the way to Belém do Pará, where in November the world’s leaders will meet to seek solutions to the climate crisis. Solutions that, for Yanda, are elsewhere.

Yanda: I believe that the answers to all the great disasters we’re experiencing are in the forests. They’re in medicine, they’re in cultures that are proposing the possibilities of other ways of living, not those possibilities of living while destroying things like: “we must invest in oil exploitation, mining and others.” That should already be moving to another plane in these times, but we’re not achieving it. And that’s everyone’s work too.

Eliezer: This is Amazonas adentro, a series from El hilo, from Radio Ambulante Studios. Episode 1: The Water Children and the Warrior Girls.

Joseph, voice note: It’s almost five in the afternoon and I’m sitting on a log on the banks of the Pastaza River, which is a very large river…

Eliezer: That afternoon, when you were at the Pastaza River, you recorded a voice note that you sent us.

Joseph, voice note: And we’ve made a stop to be able to inhale some liquid tobacco.

Eliezer: You sound a bit melancholic in that voice note. How were you feeling?

Joseph: Well, I’m always melancholic, right? It’s my way of being, let’s say. But I think in that particular moment it was partly the effect of the tobacco too and the conversation, which was a very deep conversation. But also because I was thinking a lot about how to capture everything I was hearing and seeing from this trip.

Joseph, voice note: My mind hasn’t stopped thinking all the time about how this trip will go for me.

Joseph: Because of course, wanting to tell the story of the river, wanting to tell the story of the forest is an impossible endeavor, because there are so many stimuli there, so many things happening at once.

Joseph, voice note: Trying to tell a coherent story, a story that can interest people, that can express what I’m experiencing and seeing here.

Joseph: And it’s like entering the river with humility, right? I mean, there were many other people who wanted to tell the story of the river before me, and after me there will be many others. I’m just a limited person who is going to try to capture part of the experience of traveling the Amazon River. And the other thing was certainly also thinking about the people one loses. My father passed away just a year ago. I thought a lot about him. I thought a lot about my grandmother too.

Joseph, voice note: I myself am partly Amazonian through my grandmother, but sometimes I feel that connection has been lost at some point in history.

Joseph: She passed away some years ago; she was a woman who was born in an indigenous community in the Peruvian Amazon.

Joseph, voice note: That maybe they can be accompanying me on this trip too. That they travel with me, right? Or that’s what I want to believe too.

Joseph: I was thinking about why I was there. I mean, what the hell am I doing here? I mean, why is there something in me that over the last, I don’t know, the last decade has been throwing me to go to the Amazon? I’m convinced that all people resonate with a specific geography. I mean, there are people who resonate with the oceans, others who resonate with the desert. In my case, I think because of living in my Amazonian grandmother’s house, I resonate with the jungle, despite being a city person, right?

Joseph, voice note: The truth is I have a bit of fear. A bit of anxiety too about knowing how to do this work.

Joseph: But when I took the ayahuasca, for example, it was that night, I took it with Yanda and I had obviously prepared myself, I bathed in the river, right? It was just him and me. I was lying on the floor of the cabin and suddenly I began, while awake, I began to perceive the sounds of the jungle in a way I had never felt before. I began to hear very fine sounds. Not only the insects, the birds, some crawling animals, the sound of the river, but everything at once. As if it were a great symphony, I don’t know of nature. But with such, such, such great clarity that I felt it was like a kind of message. To say: “Ah, well, maybe, all I have to do is listen.” Listen. Be attentive to the sounds, to what people have to tell me, talk less, think less, and listen.

Joseph: After the Pastaza River I went to a city called Tena, a town that’s about an hour and a half by car from Puyo. And I went in the truck of a friend named Darwin. A Quiteño, a musician. A Latin American music artist who plays the panpipe, the quena. Truly a great artist. And we went in his car listening to music, the recordings he’s made. It was a very fun trip.

Well, Tena is a very particular city. When you arrive at the city, at the entrance to the city, you can see a kind of welcome arch. And in the corner of that arch there’s like a large, large sculpture of a man in a kayak. So just seeing that already gives you an idea of what the main activity of that place is, right? That is, it’s a city where many tourists go to kayak on the rivers. But at the same time, just as there’s this sports practice on the Jatunyacu River, there’s also a very strong economic activity linked to gold mining. We’re talking about artisanal mining, often done without a license. And on other occasions done with a license, with permits, but despite that they fail to comply with environmental regulations, of course generating a very serious impact on the ecosystem, on the river, on the forest, and on the people who live near these territories.

Workshop leader: You can write a letter, it can be a reflection for… Or a drawing.

Joseph: And I was heading there because I was going to attend a series of workshops that an Amnesty International group was giving to children and young activist girls.

Workshop leader: About the following question: what was the most significant change in your life from having participated in the Warriors for the Amazon collective?

Joseph: A group of them, the children, belong to a group called Yaku Churi. Yaku is water and Churi is a child in Kichwa. And these children dedicate themselves to kayaking, right? To practise kayaking on the Jatunyacu River, which is an important river in Tena, and in the practice of that sport they generate awareness, a relationship with the river, the importance of taking care of it, of monitoring, for example, that mining isn’t done in that area. And on the other hand there’s the Warriors for the Amazon group, which is a group of girls and adolescents who live in Sucumbíos, which is a province where there’s a lot of oil exploitation. And they do activism to be able to defend their territories from that contamination caused by oil and gas flares. So, it was a meeting of these two groups who were going to receive a series of talks, advocacy workshops—as they call them—to develop communication strategies so that authorities, decision-makers, can somehow do something to be able to protect the territories, the forests, and the place where they live.

Silvia: I see. And were you able to talk with some of these boys and girls?

Joseph: Yes, of course. I tried as much as possible not to interrupt the workshop too much, but I was able to talk with them.

Leonela Moncayo: Well, let me introduce myself, my name is Leonela Moncayo, I’m 15 years old, I’m from Sucumbíos province and now I’m a warrior for the Amazon.

Joseph: Leonela Moncayo is a human rights activist. Well, she’s still in school. And it was incredible to meet her because she really didn’t seem like she was 15 years old. She seemed like an older person to me.

Leonela: Our work is to fight against the flares that, well, at the moment they extract oil from the subsoil they don’t reuse that gas, but instead what they do is release it into the open air, using it irresponsibly by burning these flares.

Joseph: The flares are enormous metal structures. They’re like long pipes that project from the earth toward the sky, and if you see them from a distance, they look like enormous Olympic torches. But in reality they’re part of an industrial natural gas burning system, which operates at an average temperature of about 400 degrees Celsius. That’s a lot of heat. And in that process it also releases gases that are very toxic to the health of the people who live in that territory.

Leonela: I’ve had the flares close, a flare that was near my house, that was in front of my house. I could see it every night, I heard it every day. The stench that this flare expelled every day was terrible. The heat when it was hot days was worse, because that stench arrived worse when it was hot days like that.

Joseph: So she told me, for example, that when she was nine years old was when she started, let’s say, in this work, in this activity of defending the territory and that throughout all this time she has seen how the flares and the oil pollution have been affecting, not in other people, but in her own family.

Leonela: Up to now the place is no longer very good for agriculture or for cultivating crops. My family has cacao, but the cacao doesn’t produce as much as it used to. In my community we don’t have drinking water either. We use rainwater, which is the worst, and yet it’s the only thing we have left.

Joseph: In the provinces of Sucumbíos and Orellana there are records of an increase in cancer cases. In 2021, for example, UDAPT documented 251 cancer cases. But then by 2024 the number of people with cancer rose to 531 cases. Of the total of all these people, 73% are women. So when I spoke with Leonela, she told me that she also has family members sick with cancer. In fact, her house is very close to a flare, to these pipes that look like large Olympic torches.

Leonela: I always have skin problems. Me, my family. I’ve also had family who have suffered from internal tumors, in the breasts…

Joseph: And due to the activism she’s been doing, and being so vocal, let’s say, in the face of these injustices, she told me that she’s even been affected by some kind of threat, or some kind of attack.

Leonela: They’ve tried to silence us. I had an attack at my house, they’ve detained the buses we always travel on to Quito, they don’t allow us to march.

Joseph: That they’ve thrown explosives on her neighborhood corner when she, just a few days before, had made some public statement, right? About that. So what they’re doing is not something, it’s not something minor, right?

They managed to get the Provincial Court of Justice of Sucumbíos to rule in favor of the lawsuit they filed, which is a lawsuit for the elimination of the flares adjacent to communities and populated centers. In 2021 the Provincial Court ruled in favor of this lawsuit so that, by 2023, these flares would disappear. So, at the time of the ruling, for example, at that time there were 447 flares, but now there are 39 more flares, that is, there are 486, which are in the jungle of Napo, Sucumbíos and Orellana, which are the provinces that are in the north of Ecuador’s jungle. So, of course, not only have they not complied with making the ruling effective, but they’ve increased the flares. So in August of this year, these girls filed a non-compliance action against the Ecuadorian State before the Constitutional Court. So they’re demanding that the ruling be enforced. But it hasn’t happened, rather a few months ago, just in July, the president of Ecuador, Daniel Noboa, ordered that the Ministry of Environment be merged with the Ministry of Energy and Mines, right? That is, now all the functions that the Ministry of Environment fulfilled in auditing, in ensuring that there are no environmental abuses by industries, now that work will be done by the Ministry of Energy and Mines. That is, there’s a judge and party, right? So, clearly the current government of Ecuador has a line of work, or of doing, let’s say, of not complying with this type of ruling that helps reduce the impact of the climate crisis. On the contrary, right? So, again, it’s like returning to this dream of Yanda’s, that it’s a train that has no destination, that doesn’t have visible leadership to be able to change things.

Eliezer: A break and we’ll be back.

Silvia: We want to tell you that next Thursday, October 23rd, Central returns, the series channel of Radio Ambulante Studios, with a story that impacted us from the first moment: a disturbing, private tragedy that ended up focusing on the continent’s largest bribery plot.

Eliezer: La Ruta de Sol reconstructs a case that shook an entire country, and tells the story of a family and a handful of people who were trapped in that blurry border where economic power, political power, and corruption intersect. You can listen to it starting next Thursday at centralpodcast.audio, or on any audio app. Here’s a small preview:

David Trujillo: At the end of 2018, a family tragedy exploded in Colombia… We’re going to reconstruct the shocking case of the death of Jorge Enrique Pizano, one of the main witnesses in the Odebrecht case, and three days later that of his son, Alejandro.

Juanita: I immediately asked him: Who killed my dad? Who was it? Who was there?

David Trujillo: The story of two deaths, a bottle of poisoned water, and an international corruption network. Listen to La Ruta de Sol on Central on the iHeartRadio app, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you listen to your podcasts.

Silvia: We’re back.

Joseph: And what can you see when you pass through there, for example, when you go by with the kayak?

Jair: Before, when we passed with the kayak it was only green. We looked from one side to the other, and it was only green.

Eliezer: Before the break we met Leonela, one of the girls from Warriors for the Amazon who was participating in a workshop with the boys from Yaku Churi. Joseph also spoke with them.

Jair: Right now, since the miners have entered, you go, you see a bit of green, then you see mountains of stones, machines, stones changed colors, the dirty river. Since mining washes the gold, it dumps all the water into the river.

Joseph: I had the opportunity to talk with one of the children, whose name is Jair, whose family, some relatives work in mining in that area.

Jair: Before it was super nice to hear the sounds of nature. It was super nice. Now you only hear the machines how they’re destroying, how they cut down the trees. And it’s ugly, truthfully.

Joseph: I mean, you pass by and you can clearly see that.

Jair: Yes, clearly. They’re right next to the river.

Joseph: And Jair was telling me about how the contamination from mining and the presence of mercury use, which is a toxic metal, is affecting, not only the quality of the water, but also the quality of the fish they consume.

Jair: There are fish that are mutating, and they die.

Joseph: Also affecting tourism in that place a bit, because by doing mining they also destroy the ecosystem and the place where the river… where the river passes, right? So, a very lucid kid, and who had things very clear.

Jair: Mercury causes mutations, so it’s really ugly how they contaminate. The people who live off the river can no longer drink it. They can’t. They can’t anymore. The river is dying.

Silvia: Well, as you were saying, these kids sound older than they are. Right? Leonela is 15, Jair is 14. And they sound very prepared to talk about these very complex issues. So we’d like to better understand what’s behind all this, behind the formation of these kids. So, tell us about the adults who were organizing these workshops? Who’s behind Yaku Churi, for example.

Joseph: Well, on the Yaku Churi side, of these water children, let’s say, the founder of this association is Diego Robles. He is also a young man. Diego is only 35 years old, too. And he’s a kayaking expert.

Diego Robles: I shouldn’t exclude that I also dedicate myself to the tourism activity and to woodworking. Those are my strengths. But all of this always goes together.

Joseph: And he was born in Sucumbíos. That is, he was born in the province where the girls or the Warriors for the Amazon are from, from that same area, from a specific town called Shushufindi. It’s a town where there are also oil plants, there are also flares. And Diego told me that this whole idea of working in favor of nature and in favor of reducing the impact of industries, of opposing, let’s say, mining extraction or oil extraction in Ecuador’s jungle, started because his mother died of a strange illness, possibly cancer, due to the proximity that her house had to one of these flares, which release toxic gases and affect people’s health.

Diego: She lived 100 meters from an oil flare. 100 meters, where they burn oil gases, and she was contaminated. And I hadn’t even been born. I’m talking about the year ’85, around there when there was the oil boom. Texaco, at that time.

Joseph: So, when he moves to Tena to be able to work, again in this tourist industry, kayaking and such, he said: “Well, I don’t just want to be a tourist guide, but I want to do something to be able to protect this river where I practice my work, practice my sport.”

Diego: Seeing here what’s happening, what started to happen with the river issue, mining, destruction, of course, that’s where all the connection comes from. My mother physically disappeared. But who is the true mother? The one who sustains us. The earth, the water. Life. She feeds us. She sustains us. Every oil well, every excavator digging, it’s like they’re drilling a hole in your mom’s lung. That’s the thing. We’re killing our mother. It’s not just a thing, it’s a living being. It’s our mom. So for me this connection came very strongly to my head, this that’s happening, this that happened with my mother, to what’s happening now with our Amazon, with our planet in general.

When I started to see the river suffer, that’s when I decided to transform the sport.

Joseph: Diego decides to practice his work and his sport in a much more integral way. It’s not only going to be my means of work, but it’s also going to be a purpose to fulfill, to take care of the river. So, through teaching kayaking and doing tourism in kayaking, Diego Robles teaches these children to take care of the river, the importance of taking care of the river, of monitoring it, the possibility of practicing, of making a living doing sustainable tourism through that sport.

Diego: And wow, when I saw these kids on the Jatunyacu River, there you go back to your childhood. Something about the Yaku Churis is that I was one of them. Or I am one of them. Without support, economic support. Without a person to push you. And I realized they had a lot of talent for the river. But there was no education. I mean, they have talent, they’re skilled. They work the land, everything. But there was no education.

Eliezer: A while ago we heard a bit from Jair about what he sees when he’s in the kayak. But what did Diego tell you about these kids? What situations do they live in and how does kayaking help them?

Joseph: Well, many of these children—because most of them are pre-adolescents, let’s say, they’re, I don’t know, 10 years old, 11 years old, 12 years old, right? And these kids, well, they live in families with limited economic resources.

Diego: They have very hard stories. Mainly, most parents have problems with alcoholism, domestic violence. And the hardest case is Tupac’s, who was already getting close to the gangs in Tena.

Joseph: His brothers had been murdered by gang members related to drug trafficking. One of his relatives had also worked in illegal gold mining.

Diego: So it’s the strongest case. And it’s one of those that has developed the most, the interesting part. He sought to transform himself and now he’s sustained there. He wants to be a kayaker in his life and be professional in that.

Joseph: Sometimes, due to the absence of the State—Ecuadorian in this case—and the absence of possibilities of other possible futures, they find themselves thrown into those types of economies. Because there’s no other way to suddenly earn money, to be able to progress. So they feel pressured in that direction. So, what Yaku Churi does through kayaking is show them another possibility for a future. That is, Hey, you don’t have to choose that path. You can choose others.

Diego: I believe there’s no better school than the river. Yes, because the river flows and you have to learn to flow with the river. You understand? It’s the same as in life, it’s like managing yourself like that, facing problems, situations, knowing how to face them, knowing when to be able to walk quickly. Or I dare this rapid, but I know the rapid will sometimes give me a tumble. The main thing it teaches is strength, mental strength.

Joseph: Kayaking gives them a work tool. In fact, many of them have decided to practice that sport. They participate in competitions. And it’s incredible how they practice the sport and how that also gives them security, right? To be able to do something very different from what poverty probably throws them to do.

Silvia: And what do you think Diego wanted to achieve by bringing together the Yaku Churi with the Warriors for the Amazon? And how does it perhaps connect to his mom, right? Because you were telling us that the warriors are from the same place as his mom was.

Joseph: Yes, totally. Well, Diego is a passionate young man. Very sensitive, right? And he told me that when he saw and heard these young girls speak with so much confidence, with so much courage, he remembered his mother.

Diego: Sometimes already, I think in the workshop a few times the tears were coming. I couldn’t anymore. I mean, I held back for, I don’t know, for courage, let’s say. Not… Not to show the children that. But of course, seeing some girls fighting for something my mom died for…

Joseph: He remembered his mother, and remembered why he was doing what he was doing now, right? To protect the river, to defend the river. And for him, as founder of Yaku Churi, it was very important that his children, the Yaku Churi children, be inspired by that empowerment, be inspired by that courage, with that eloquence when speaking and defending their rights.

Diego: This workshop is practically so they understand the reality of what they’re part of, because sometimes, they think it’s just kayaking, carpentry, but so they understand the reality of their voice as defenders of the territory.

Joseph: Diego wanted the Yaku Churi to be inspired by that, right? And they could also learn tools through example. Ah, look, those girls are your same age, and they speak with courage and they’re not afraid to say what they think, etc. So, I think that space was created to be able to share those experiences, while the girls, the Warriors for the Amazon, taught them by example with this, with their discourse, with their way of being and so on, the Yaku Churi taught them a little about the river, right? About how to conduct oneself on the river. There was a moment when we all went to the river to kayak, to do rafting on the Jatunyacu. And I think that was a very, very beautiful moment of sharing between both groups.

Eliezer: After the break Joseph goes with the Warriors to the Amazon and the Yaku Churi to navigate the Jatunyacu River. We’ll be right back.

Silvia: We’re back on El hilo.

Diego: The river is going to be a bit faster than normal, but it’s still very fun. There are some good waves, big ones, super cool.

Eliezer: How was that day of traveling by kayak with these kids?

Joseph: Well, it was very exciting, right? I had never done this sport on any river. In fact, I don’t know how to swim. I don’t know how to swim. So, I remember we all went on a bus.

We were a large group, right? I’d say well… How many people? At least more than 30 people. There were the children from Yaku Churi, there were the Warriors for the Amazon.

There were some guides too who were going to steer each of the rafting boats, which are like inflatable boats, right? Where six people go. And the kayaks, which are these individual little boats. So in the individual kayaks went the Yaku Churi, right? Who are the ones who know how to do that sport. And in the large inflatable boats went those of us who didn’t know how to do that sport. Each one with a guide, right?

Joseph: We keep rowing… I think we’ve hit a rock.

Diego: Stop!

Joseph: So we were all going down the Jatunyacu toward the Napo, because Jatunyacu joins with another river and they form the Napo River. So we were going toward there. It was a trip more or less… Because we made some stops, right? We’re talking about an hour and a half more or less. And throughout that trip, which was very exciting because there were moments where there was a rapid and there were rocks and there were waves that were forming. And suddenly we all got our clothes wet. I had the recorder there, in a space in my life jacket. And I was trying to follow Diego’s instructions, who was in my boat, but I didn’t know how to row, and all I could do was, let’s say, I don’t know, try to go forward.

Diego: Look, all this is mining, look. All in front is mining. All those stones.

Joseph: And I was talking with Diego about what we were seeing, right? And as we were crossing the river, Diego was describing it to me: mounds of earth on the banks of the Jatunyacu River and some tractors, right? The presence of freshly removed earth, as if it had just been stirred up or churned by the machines, right? And there it was—the presence of mining.

Diego: The mining, as you yourself can witness, is totally destroying the river basins and that’s also an impact, because this influences there to be landslides, for the river to lose its course. But also, well, something that also impacts me, is seeing how nature has made the decision to clean itself. For example, there I saw at least two mining points that have been flooded and now the mining holes are practically covered. The river is reclaiming its space, its territory. It’s incredible.

Joseph: We’re going to stop here, right?

Joseph: We made stops and climbed the hill to see a little further inside and we saw, well, the devastation. There were hectares of deforested forest. A kind of brown pools where there was at some point the exploitation of minerals. We also saw kinds of cabins that had been built. At that moment there was no one. But we could see, let’s say, the effects of mining in certain parts of the Jatunyacu basin.

Joseph: Totally soaked.

Joseph: Well, in the end we traveled that hour and a half of the river, nothing happened. I didn’t fall in the river, thank goodness. But it was very exciting to have made that trip.

Joseph: How was it? How was the trip?

Girls: Good, very good, beautiful. Excellent.

Joseph: Did anyone drown?

Girl: No, but you have to experience…

Silvia: In the next episode…

Wilmer Lucitante: For oil companies we’re a thorn in their shoe because we tell the truth.

Frank Jurado: We’re in a very rich sector, where there’s oil exploitation. But what good is it to us if we live in misery?

Jamileth Jurado: Until the last moment that the contamination ends, I believe we must fight, because our families are going to live in contamination.

Pablo Fajardo: And we do it because I say: “at least I don’t want to be and I won’t be an accomplice to those crimes.”

Eliezer: This episode was produced by Silvia with the reporting by Joseph and the research of Rosa Chávez Yacila. It was edited by Daniel Alarcón and me. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. The sound design is by Elías González with music by Remy Lozano.

The rest of El hilo team includes Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask you to join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to go deeper into today’s episode, subscribe to our email newsletter by going to elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it every Friday.

You can also follow us on our social networks. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook and Threads. You can find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share the episodes.

I’m Eliezer Budasoff. Thanks for listening.