Crimen organizado

Poder ilegal

Economía ilegal

Estado, Corrupción

Violencia

Seguridad

Desigualdad

El crimen organizado en América Latina ha dejado de ser un asunto vinculado principalmente con el narcotráfico, el secuestro y la extorsión, para convertirse en una red de actividades lucrativas mucho más amplia, que atraviesa la vida cotidiana, la economía y la política. Por un lado, las grandes organizaciones criminales han diversificado sus negocios y expandido su control territorial, lo que ha consolidado su poder frente a la ineficacia o la complicidad de los Estados. Por otro, el enfoque en la persecución de estas estructuras desvía la mirada de los mercados ilegales, que es donde está el dinero y el origen de su poder. Esta semana conversamos con la socióloga Lucía Dammert, especialista en temas de seguridad, para entender por qué es importante hablar de “poder ilegal” en la región, y qué revela su consolidación sobre los límites —y las renuncias— de la política frente al crimen y la desigualdad.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Jesús Delgadillo -

Edición

Eliezer Budasoff, Silvia Viñas -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción digital

Samantha Proaño, Franklin Villavicencio, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Elías González -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

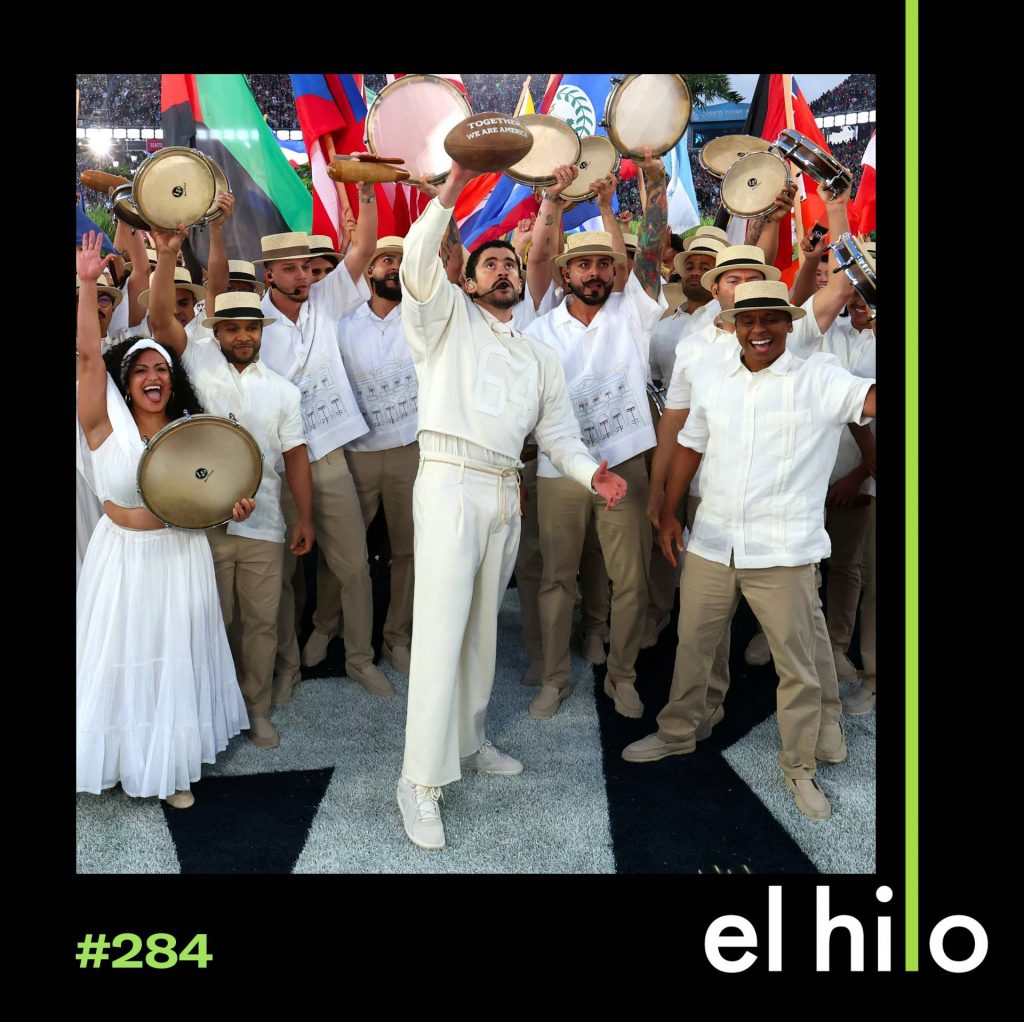

Fotografía

Getty Images / Johan Ordonez

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Eliezer Budasoff: El hilo se financia gracias al apoyo de sus oyentes y de diversas organizaciones, entre ellas Grupo SURA, gestor de inversiones con foco en servicios financieros. SURA impulsa el periodismo independiente que fortalece la democracia en América Latina y contribuye a una ciudadanía mejor informada.

Silvia Viñas: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: Y yo soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Eliezer Budasoff: En las últimas décadas, el crimen organizado en América Latina ha mutado de un conjunto de bandas y pandillas a organizaciones numerosas capaces de alterar el orden político-social de países enteros.

Audio archivo, BBC Mundo: El Tren de Aragua es una de las bandas criminales más temidas en Venezuela.

Audio archivo, El País: Y el PCC es la organización criminal más poderosa de Brasil.

Audio archivo, DW Español: El gobierno culpó el derramamiento de sangre a las pandillas, especialmente a la Mara Salvatrucha o MS-13. El gobierno las cataloga de grupos terroristas.

Audio archivo, Grupo Reforma: Integrantes del Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación presumieron que están bien armados y blindados.

Eliezer: En el relato más común que se construye desde los medios y la cultura popular, estas organizaciones criminales aparecen como una gran red mafiosa que opera a escala continental y se dedica al narcotráfico, el secuestro y la extorsión.

Silvia: Pero la realidad es mucho más compleja. Detrás de sus nombres y sus siglas hay estructuras fragmentadas y flexibles, que también controlan la minería, el robo de combustibles, el contrabando, la trata de personas y otros delitos.

Eliezer: Este abanico de actividades mueve cantidades millonarias de dinero en toda la región al mismo tiempo que consolida poder. Un poder ilegal que lo atraviesa todo, desde la vida cotidiana hasta la economía y la política.

Silvia: Hoy, qué significa hablar de “poder ilegal” en América Latina, y qué nos revela sobre el fracaso de los Estados frente al crimen y la desigualdad.

Es 16 de enero de 2026.

Silvia: Para entender cómo funciona el “poder ilegal” en América Latina hablamos con Lucía Dammert, socióloga, docente e investigadora chileno-peruana. Lucía es especialista en temas de seguridad desde hace 30 años. En septiembre del año pasado publicó un libro titulado Anatomía del poder ilegal, donde hace una distinción clave para mirar las dinámicas criminales en la región.

Lucía: No quería hacer un libro más sobre las estructuras criminales, porque creo que eso ya… Es muy importante, pero es menos sustancial de lo que está pasando en la región. Y siento que el poder ilegal es la conjunción de un crecimiento, pues, exponencial de los mercados ilegales, con una capacidad de corrupción político institucional gigante, feroz, que en la mayoría de países latinoamericanos entra desde los lugares locales, digamos, desde los gobiernos locales hacia arriba. Pero, no son pocos los presidentes que han estado presos por lavado de activos en América Latina, ¿cierto? Y en paralelo, una atomización y una debilidad, debilidad muy grande del aparato fiscalizador del Estado y, por supuesto, los partidos políticos. Entonces el poder ilegal se constituye en aquellos lugares donde tú tienes mercados ilegales, altísimos niveles de corrupción y bajísima capacidad estatal. Entonces, a los muchos entrevistados que yo hice en América Latina para ellos muchos, incluso su alcalde electo, es un poder ilegal, porque después va preso por corrupción, porque no entiende muy bien, porque tiene familiares que están en organizaciones, digamos, en mercados ilegales. Entonces, hay una relativización de lo que es el poder legal y hay una exaltación de aquel poder ilegal que además muchas veces ayuda a la gente de una forma mucho más directa.

Eliezer: ¿Nos puedes contar un poco cuáles son hoy los mercados ilegales más relevantes en América Latina?

Lucía: Sí, mira, hay de todo, pero te diría que hay cuatro que hay que echarle mucho énfasis. Uno es la minería ilegal del oro, que está muy concentrada en Colombia, Perú, Brasil, ahora, Venezuela también, un poquito Bolivia. Casi todos países amazónicos. Y esto tiene muchas consecuencias, ¿no? Un gran problema, se estima que entre el 70 y el 80% del oro que sacamos tiene un origen ilegal, y digo tiene un origen porque luego, por diversos mecanismos que son de fácil identificación en los países, se torna legal. Pero bueno, está un poco difícil conseguir la voluntad política para luchar contra esto, ¿no? Yo creo que el caso peruano es muy evidente, pero luego esto está generando deforestación en la Amazonía, esto está generando contaminación de ríos, está generando matanza de defensores de derechos humanos en la Amazonía. Yo creo que el Amazonas es un espacio que está siendo vulnerado masivamente.

Luego tienes la trata de personas, especialmente mujeres, para el trabajo sexual y laboral, que es uno de los mercados ilegales más grandes del mundo y en América Latina mueve muchísimo dinero. Se estima más de 12 mil millones de dólares al año ¿cierto? Es un mercado además interno y externo. Hay gente, hay mujeres que las roban dentro del mismo país, ¿no? Además, ,pues, por el machismo y el patriarcado propio, nuestros países muchas veces ni siquiera está en la prioridad número uno, pues a veces la gente, muchas mujeres tratadas, son encontradas por la policía y luego expulsadas por migrantes irregulares cuando son víctimas. Yo creo que ahí también hay un fenómeno importante. Un tercer elemento, sin duda, es el tráfico de personas, ¿no? el tráfico de migrantes, que la diferencia principal es para los que están escuchando. Y es que a los migrantes van y los dejan en otro país, no es que los tienen para la explotación, sino que los mueven, pero ese movimiento es un movimiento violento, terrorífico, que se aprovecha de las vulnerabilidades de la gente. Y también, bueno, parte importante de los millones de venezolanos que se han movido se tienen que haber movido en esas redes, ¿no? Y que son redes súper lucrativas, con una capacidad de flexibilidad en términos de rutas feroces. Pero además, nadie puede decir que 3 millones de personas se movieron y ningún funcionario público los vio pasar por sus países. O sea, eso es como la demostración más grande que acá tú tienes unos espacios de corrupción, no te digo transnacionales, pero por lo pronto en muchos lugares ¿no? Y bueno, y un poco parece que nos hemos ido demasiado concentrados en el tema de drogas y los otros no, no se han visto mucho.

Yo también creo, digamos que el tema… Evidentemente el tema tala es un tema importante y los dos habilitadores de estos fenómenos que no hay que olvidarlos, uno es el tráfico de armas, ¿no? Que es feroz, que viene generalmente de armas legales, porque no existen fábricas ilegales de armas, digamos, sino que existen fábricas que hacen armas y después el tráfico es ilegal y por otro lado, el lavado ¿no? Entonces, porque estos mercados ilegales lo que quieren es legalizar su dinero. Sí quieren comprarse una casa, sí quieren comprarse un auto, no es que quieran tener la plata debajo del colchón o gastársela en pequeñas fiestas, ¿no? A veces la iconografía nos hace pensar que estos son pues esos narcos chiquitos que quieren hacer una fiesta, ¿no? Entonces para el lavado también hemos sido, digamos, como hemos sido, seguimos siendo muy poco eficientes.

Eliezer: ¿Qué tipo de otros actores intervienen? No sé. Empresas, Élites locales…

Lucía: Por supuesto. Pues pequeñas, pequeñas y medianas empresas. El sistema financiero de partida. Todos aquellos lugares donde uno tiene mucho dinero físico, ahí tienes que ponerle un ojo, tienes que poner un ojo a los casinos. Bueno, ni qué decir el gran capítulo gigantesco de los casinos digitales, ¿no? Las casas de apuestas digitales que eso, los niveles de regulación no existen. Tenemos un problema ahí muy serio, ¿no? O las mujeres que pues venden horas en la red, digo, hay una serie de mercados, pero también nosotros hoy día tenemos, pues, mercados ilegales de contrabando de cigarrillos, mercados ilegales de robo de cobre, robo de salmón, mercados de oro. Bueno, hay de todo, ¿no? cada producto que uno pueda vender normalmente va a existir su espejo, que es el espejo ilegal. Porque algunos no quieren pagar impuestos y porque a veces funciona mejor, pero efectivamente hemos ido dejando crecer estos pequeños monstruos chiquititos que creíamos que estaban controlados y han ido consolidando poderes territoriales, han ido consolidando vinculaciones internacionales y bueno, tienen consecuencias feroces en términos sociales, políticos y económicos, sobre todo porque muchas veces a sus pequeñas bandas, chiquitas, que están en el negocio de mover gente, por ejemplo, cuando no les pagan esas bandas ¿a qué se dedican? a la extorsión. Entonces, ahí se genera lo que yo creo que es el círculo más complejo, y es que luego empiezan a extorsionarte por tu día a día, a los ciudadanos comunes de la región, sobre todo a los más pobres. La extorsión es un crimen principalmente contra la población más pobre de la región, que es la que está pues saliendo desesperadamente a buscar algún tipo receta mágica ¿no?

Eliezer: Cuando se habla del crimen organizado en América Latina, específicamente de agrupaciones grandes, ¿no? como el Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación, el Tren de Aragua, el Comando Vermelho, la Mara Salvatrucha, suelen presentarse como redes o bandas internacionales articuladas. En la práctica, ¿esto es así?

Lucía: Sí, mira, yo creo que hay dos cosas que hay que tener en cuenta. Uno, tiene en la región mercados ilegales articulados. Esas economías ilegales del oro, la economía ilegal de la droga, de la trata de personas. El fin sí es articulado no solamente regionalmente sino globalmente. Y luego uno tiene las estructuras criminales que se organizan a partir de esos mercados y esas estructuras, pues, tienes algunas muy grandes en América Latina, sin duda, pues el Clan del Golfo, sin duda Sinaloa, el PCC, probablemente el tren de Aragua, pero sobre todo lo que tienes es un sistema mucho más flexible, mucho más, digamos, granular de muchas organizaciones intermedias y pequeñas que entran en contacto, digamos, un contacto menos organizado de lo que uno ve, pues, en las series de narcos cuando ve un gran señor, ¿no es cierto? Entonces me parece muy importante hacer la separación entre el mercado ilegal y la estructura criminal, porque luego cuando uno dice ¿contra quién peleamos? Uno dice vamos a pelear contra la estructura criminal y el mercado sigue floreciendo con otras estructuras.

Eliezer: Una de las cosas que queríamos tratar de entender contigo es, se habla mucho de los grandes nombres de las bandas, ¿no? Se va construyendo una narrativa y un mito y lo que en algún momento nos planteamos es bueno, ¿realmente está distribuido en grandes bloques criminales o más bien son múltiples grupos locales con dinámicas propias?

Lucía: Sí, creo que hay de todo, ¿no? Porque en América Latina tú tienes países donde los mercados ilegales tienen niveles de control territorial, político, económico, social, mucho, mucho más amplio que otros. Pues el Clan del Golfo tiene incluso una estructura política, el PCC en Brasil. Pero luego, por ejemplo, el el Tren de Aragua a mí me parece una estructura interesante. Primero porque tú tienes pues una migración gigante de venezolanos por América Latina, algunos de ellos se dedican a acciones criminales, pero no por eso cada vez que detienes a alguien que es de origen venezolano significa que el Tren de Aragua está presente. ¿Qué es lo que pasa hoy día en la región? los titulares pues se desbarata el tren de Aragua, en Colombia, se desbarata el tren de Aragua, en Perú, se desbarata el tren de Aragua en Chile. Y tú dices bueno, pero esto es más grande que Coca-Cola, ¿no?

Y en realidad tenemos que darnos cuenta que estas son estructuras que pueden llamarse parte del tren de Aragua, que pueden estar vinculadas con alguno de los negocios o mercados ilegales, que el Tren sí mueve, que es el tema principalmente de tráfico de personas, pero no por eso significa que uno entre comillas desbarató el tren de Aragua, sino que desbarató tal vez una célula de las muchísimas que hay en un país que lidia con ese mercado. Esto es fundamental porque por muchos años nos ha pasado que medimos a las policías y al ejercicio del poder por cantidad de gente de alto nivel que detienen. Entonces obviamente nadie quiere decir bueno, detuvimos cinco traficantes, sino que luego dice la célula principal y eso nos ha llevado a desviar la mirada respecto al problema central, que yo creo que es el problema de los mercados, donde está el dinero, donde se corrompe la política, donde se logra el control territorial. Y por supuesto, esto no le baja la importancia a los niveles de violencia, a las organizaciones más fuertes, sino más bien lo que te muestra es un calidoscopio criminal mucho más complejo en la región.

Eliezer: En los últimos años, por ejemplo, se ha consolidado una especie de mitología del crimen organizado. Hay líderes que se presentan como estrategas, justicieros o benefactores. ¿Cómo contribuyen los medios y la cultura popular a construir esta imagen de “el criminal poderoso”?

Lucia: Mira, es muy interesante, pues, con el tema de los medios me das la oportunidad de decir una cosa que creo que es fundamental, y es que si hay alguien que realmente sabe hoy día qué está pasando en la región es el periodismo de investigación. La mayoría de los académicos lo que logramos llegar es a los niveles más accesibles de lo que son los mercados ilegales, ¿no? Uno, pues, tú ves muchos estudios que están como concentrados en las pandillas de las esquinas, en los medianos productores. Pero cuando tú ves el trabajo que hace el periodismo de investigación muy serio de América Latina, pues, están en los territorios, están semanas, tienen una nivel de granularidad importantísimo, entonces también por eso es que han matado tanto periodista de investigación. Conocer esto desde las capitales no se puede. Entonces esa es una parte, la otra parte es un poco la búsqueda de la espectacularidad, que si hay delitos muy violentos, que sí ha aumentado, digamos, la violencia en países donde antes no había tanta violencia como Uruguay, Chile, Costa Rica, que hay una, entre comillas, democratización del de los mercados ilegales en casi toda la región, que hoy día el fenómeno de la extorsión no es un fenómeno colombiano, ni mexicano, sino es un fenómeno, pues, transversal. Y eso para los medios, la tentación del titular sangriento que finalmente además se mezcla mucho con la crisis de los medios de comunicación tradicionales que están en la pelea por el clickbait, digamos. Si no ponen un titular sangriento nadie va a ir a leer una noticia que sea, pues, detuvieron a cinco criminales. Nadie va a hacer el clic para mirarlo en las redes, que es donde estamos hoy día enterándonos de todo. Entonces es un círculo ultravicioso. Además, digamos, parte del fenómeno que traemos es que, digamos, esta espectacularización de la violencia, esta normalización de la violencia cotidiana, etcétera, también trae, pues, una frustración muy grande por parte de la ciudadanía que ve que el Estado no responde, que los problemas no se resuelven. Y por supuesto, está aterrada, ¿no?

Eliezer: Este terror, digamos, y esta narrativa ¿cuál es el efecto que ha tenido, en términos electorales y para la democracia en la región?

Lucía: Es que la seguridad es un gran negocio para los criminales, pero también es un gran negocio electoral, ¿no? Lamentablemente no desde ahora, digamos. Desde hace muchos años la seguridad fue lo que permitía diferenciar la izquierda de la derecha, ¿no? Entonces, la izquierda decía salario, protección, etcétera y la derecha decía no, acá necesitamos más control, hay un problema de seguridad, ¿no? Pues los jóvenes pobres, en fin. Y ahora la izquierda se ha quedado sin su parte más de protección social y lo que estamos ya es en una situación muy generalizada, donde el discurso natural de todos, de izquierda y derecha, es que el problema es este enemigo, digamos, narcoterrorista o bueno, en fin, extranjero principalmente. Es muy interesante cómo en la región ha desaparecido, prácticamente en casi todos los países, el concepto de prevención ¿no? O el concepto de rehabilitación post penitenciaria. Entonces, la gente tiene todo el derecho de sentirse angustiada porque lo que ve es que nadie los protege.

Lo que ve es que cuando denuncia la policía no llega. Que cuando la policía se lleva a alguien, luego ese alguien regresa y termina uno siendo víctima. Con el aumento de la extorsión, la gente ya no solamente tiene la impresión de que tal vez puede ser víctima, sino sabe que su vida cotidiana está siendo enfrentada, pues por unas estructuras digamos pequeñas o medianas, pero que igual impactan en su vida. Y lo que quiere es respuestas. Y hemos sido muy incapaces en la región de tener respuestas sostenibles, duraderas, de largo plazo, que muestren resultados. Ha habido cosas interesantes, sí, pero políticamente las han cambiado. Bueno, entonces al final del día la ciudadanía valora la mano dura, el castigo, la represión, incluso cosas que la ciudadanía sabe que no van a no van a poder funcionar, como por ejemplo la pena de muerte. Pero la sensación de que tú vas a tener a alguien duro.

Lucía dice que este no es un fenómeno reciente, que incluso en la época en que había una hegemonía de izquierda en la región, algunos gobiernos empezaron a incorporar a exmilitares en sus gabinetes para dar una imagen de firmeza.

Lucía: Y eso genera entonces un rédito electoral. Bueno, que lo vemos en el caso hoy día en América Latina, en las elecciones. Hubo un momento, hace unos seis meses atrás donde decían queremos un Bukele ahora que ya se dieron cuenta que pues el fenómeno Bukele le trae negociación con las pandillas y le trae ajusticiamientos, etcétera. Ya algunos han dejado de pedir un Bukele, pero pues la receta es una receta muy parecida y mi impresión es que el daño que se le hace a la democracia es gigante. Pero también hay que hacernos cargo que los partidos políticos que pues reconocen la necesidad de la democracia, han hecho poquito para que la ciudadanía esté contenta y esté realizada, o por lo menos sienta que hay un esfuerzo ¿no? La ciudadanía yo creo que con derecho está muy molesta.

Eliezer: Bueno, uno de los motivos por los cuales queríamos hablar contigo fue la matanza reciente que hizo la policía de Río de Janeiro en las favelas.

Silvia: En octubre de 2025, algunas semanas antes de que entrevistáramos a Lucía, un megaoperativo policial en Río de Janeiro dejó más de un centenar de muertos y se convirtió en el más letal de la historia de Brasil.

Audio de archivo, France24: Decenas de muertos, barricadas e incendios en una mega operación antidrogas en Río de Janeiro, en Brasil. Más de 2.500 agentes, vehículos blindados y helicópteros participaron en la incursión contra el grupo criminal conocido como Comando Vermelho, o Comando Rojo, uno de los más poderosos de Brasil.

Eliezer: Después salieron unas encuestas de cuál era la opinión de la gente al respecto, y el mayor índice de aprobación, pero era altísimo, era el de las favelas.

Lucía: Pues a mí no me sorprende. ¿Por qué? Porque en este nuevo orden criminal que hay en América Latina, donde a nivel local ya no hay tanto robo. Hay, pero ya no hay tanto robo de celular, ni robo de autos, sino lo que hay es extorsión. Extorsión para entrar a tu casa, extorsión para salir de tu casa, extorsión para ir al colegio, extorsión para manejar tu taxi. La gente está viviendo unas condiciones muchas veces muy terribles. La extorsión es un, yo creo que es, probablemente el elemento criminal más complicado hoy día en la región, porque la extorsión cuando llega es muy difícil sacarla, porque es una forma de ganar dinero rápido, totalmente impune- Entonces tú ves, en los sectores más populares, una visión mucho más dura, ¿no? Lo ves en las elecciones, los votos de la derecha, ultraderecha, más dura está mucho en los sectores populares que están pidiendo, digamos, a gritos, que por favor alguien les resuelva el problema. Y se convierte en una forma de relación social. Entonces entiendo que incluso esto que ha pasado en Río, que es dramático, porque al parecer ha habido, digamos ahí un ajusticiamiento pues muy grande y tal. Al ser jóvenes que son reconocidos como parte de una pandilla, cierto, o de un grupo criminal, bueno la ciudadanía siente que por lo pronto algo está pasando. Ya es tiempo.

Y esto nos lleva a una discusión que creo que también tenemos que entender es que en muchos espacios de la vida latinoamericana el concepto de derechos humanos está siendo redefinido y los especialistas a veces no lo vemos. Seguimos con la discusión de los derechos humanos post dictaduras, post guerras civiles y en realidad para muchos latinoamericanos hoy día la conversación es distinta.

Silvia: El operativo policial en Río de Janeiro del 28 de octubre tenía como objetivo capturar a los líderes de alto rango del Comando Vermelho, pero eso no sucedió. Más de 100 personas terminaron muertas. Organizaciones como Amnistía Internacional y el Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales catalogaron el hecho como una masacre y un ejemplo más de violencia sistémica.

Eliezer: En una audiencia del Senado, el subsecretario de inteligencia de la policía militar de Río declaró que la redada tuvo un impacto “insignificante”. Los residentes de las favelas dijeron que la operación hizo poco por detener la violencia y el control territorial.

Hacemos una pausa y ya volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Eliezer: ¿Qué significa hablar de gobernanza criminal? ¿De qué manera el crimen organizado participa o sustituye funciones del Estado?

Lucia: Sí. Mira, durante muchos años tuvimos la idea que en donde no estaba el Estado los criminales se hacían cargo, ¿no? Yo creo que eso en la región pasa hoy día menos, porque el Estado está en casi todos lados. Lo que pasa es que el Estado tiene una relación ambivalente con las economías ilegales. En algunos casos las administran, en otros casos miran al costado, ¿cierto? En otros casos son parte directamente. Lo que tú ves a nivel local, tú tienes, no sé, grupos criminales de 100 personas y cinco policías y un fiscal y dos fiscalizadores de tala que ven las lanchas pasar y te dicen bueno, yo realmente no sé qué hacer acá porque yo tengo un bote casi que de remos, ¿no? Entonces la diferencia que hay es gigante. Ahora eso yo creo que nos aleja del concepto de estado frágil, ¿cierto? Que se usó mucho tiempo, estado frágil o estado pues directamente este.

Eliezer: Ausente.

Lucia: Claro, porque en realidad en muchos países el Estado sí está, pero está cumpliendo otras funciones, está mirando otras cosas. Y lo que creo yo, y bueno, muchos autores también latinoamericanos,pero sobre todo muy basado en lo que hace el periodismo de investigación, te diría yo, es que el Estado empieza a beneficiarse de las economías ilegales. Entonces, no son pocos los gobernadores de muchos países que te dicen bueno, el contrabando igual es una forma de subsistencia. Tú dices: bueno, el contrabando,puede ser. Pero al final del día, estos están contrabandeando gente, niños, riñones. Digo, el sistema se ha multiplicado. Entonces, creo que sí, es una cosa que tenemos que ver con mucho peligro. Porque es muy difícil cuando ya se constituye un estado mafioso. Cuando ya se constituye, digamos, el poder ilegal pasa a tener un rol más importante. Luego, realmente los ciudadanos a quién le podemos pedir justicia, paz, ¿no?

Entonces ahí en algunos países yo creo que esto está mucho más avanzado. Me parece que en el caso mexicano, que es un caso que lleva pues muchísimos más años de deterioro por su cercanía a Estados Unidos, pues es muy interesante que resulta que allá se vende toda la cocaína, pero los narcos somos los que estamos de este lado. Es muy rara la conversación, es muy rara. Es muy raro todo lo que nos está pasando. Pero claro que en México hay, además de estos fenómenos de mercados ilegales, así como en otros países también pequeñas colonias, barrios, barrios enteros donde el gobierno lo establecen estas organizaciones medianas, pequeñas y grandes. En el caso mexicano es mucho más evidente porque la capacidad de armas es muy fuerte y porque el mercado es gigante. Cuando uno mira lo que, olvidémonos ya la cocaína, digamos el robo de gasolina y petróleo de Pemex, ese es un mercado multimillonario. Entonces tú dices ya, ok, bueno, ese es un mercado multimillonario, hay muchas estructuras, donde está, nuevamente, donde se está invirtiendo esa ganancia y creo que ese es… estamos en un momento justo para hacernos esas preguntas antes que la situación pueda empeorar.

Eliezer: Aparte, esto que decías de en México todo lo que surge como un problema cuya solución cuesta, es un negocio que termina estando atravesado por el crimen organizado, ¿no? Tú decías el negocio millonario del huachicol de combustible de Pemex, pero el agua ¿no? Cuando hay problemas de agua y las pipas de agua ¿no? Y me gusta mucho esto que dices de cuando nosotros creemos, el Estado está débil o el Estado está ausente, en realidad no es que está ausente, está presente de una manera muy particular.

Lucia: Claro, con un cierto nivel de ambivalencia, ¿no? Porque tú podrías decir oye, el Estado no es que tengamos zonas donde no hay educación, salud. No es que no haya vías, no haya vivienda social. El Estado está presente, pero claro, lo que sí ha faltado en muchos casos es capacidad policial, justicia ¿no? Pero claro, nuevamente justicia, policía y cárcel no va a resolver este fenómeno. Va a resolver algún fenómeno. Por supuesto, necesitas mejor policía y nada como México te reconoce que que una buena policía sí te ayudaría, digamos, a resolver otros fenómenos. Porque además hay una cosa que es muy importante en la región y es que casi la mitad de todos los… nosotros pues ya han visto el típico dato, ¿no? Que nosotros representamos el 8% de la población y el 30% de los homicidios del mundo. Pero la mitad de esos homicidios son gente matándose con sus vecinos, gente matando a sus familiares. O sea, no es que el 100 por ciento está vinculado al crimen organizado. Sí, también tenemos un problema de violencia muy fuerte y a ese problema de violencia, como estamos tan hiper concentrados en algunos fenómenos criminales más organizados, a veces los hemos dejado de lado. Y eso también requiere, digamos, ser, ser mirado ¿no? Es un calidoscopio difícil. Ahora, por supuesto, una cosa es, pues, México, que es un país grande, un país rico. Y otra cosa es lo que está pasando en Haití, ¿no? Que Haití ahí sí que ya no podríamos hablar, digamos, de una estructura estatal, sino más bien de los remanentes de lo que es la capacidad estatal, de los remanentes de lo que es el Estado de Derecho. Y América Latina mira absorta y el mundo entero mira absorto lo que está pasando ahí, ¿no?

Eliezer: ¿Por qué resulta tan difícil romper este tipo de vínculos, esta convivencia de negociación entre actores estatales y actores criminales, incluso en democracias consolidadas?

Lucía: O sea, pues el problema, mira, si seguimos la línea de entender esto como mercados ilegales, economías ilícitas que generan, pues, cientos de millones de dólares en la región, la pregunta que viene a continuación es ¿dónde está ese dinero? Y ese dinero no está en las manos de prácticamente ninguno de los presos de América Latina. Ni uno. Los presos latinoamericanos son hombres pobres, analfabetos, con problemas de consumo, principalmente. Entonces, lo que pasa es que ha sido muy fácil para los sistemas de justicia criminal y para la política concentrarnos en indicadores de decomiso, detenciones. En decir bueno, yo he comprado mil vehículos porque en el fondo pues decir por ejemplo, que hay problemas de lavado, que hay economías enteras, regionales que se sustentan en dinero que es ilegal, que hay partidos políticos que son financiados por organizaciones criminales, es pues muy difícil de sustentar en el mediano y largo plazo en muchos países. Entonces, esta es una cuerda que ha girado hacia, entre comillas, lo más sencillo, que es buscar una amenaza que por muchos años, mira, yo trabajo esto ya 30 años, pero por muchos años este tema la amenaza era el joven popular ¿no?

Todas las imágenes eran los jóvenes populares, que son los que van y te van a robar. Te van a violar, en fin. Pero esa amenaza ahora la hemos transformado en una amenaza terrorista internacional, que son las agrupaciones principalmente extranjeras, ¿no? Que están vinculadas con alguna, pues, de estas estructuras criminales gigantescas. Y eso nos permite, entre comillas, en algunos países olvidarnos, pues, los cientos de miles de jóvenes sin educación, sin trabajo, sin bueno, todos los problemas de base que hay, que son los soldados que fortalecen ese ejército del mercado ilegal, cierto, y lo que hace es nos concentra en las respuestas más, digamos, internacionales si quieres o las respuestas más de control y justicia. Entonces, ahí hay una trampa de la que tenemos que salir. Porque además la verdad es que si ponemos ojo en el tema del mercado, la mayoría de los países han tenido muy poquitos resultados en la lucha contra el lavado, el control del ingreso de armas y eso pues no… Ni qué decir de, pues, la minería ilegal, la venta de drogas, etcétera.

Silvia: Hacemos una última pausa y ya volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta.

Eliezer: Me gustaría poner, como en su justo lugar, esta idea que tenemos de que, por un lado, las estructuras criminales son un modo de ascenso social para gente que está en los márgenes geográficos y sociales. Pero por otro lado, también ¿cuánto hay de opción en lo que hacen?

Lucia: Bueno, es que cuando tú sales de las ciudades capital, porque cuando sales de las ciudades capitales de América Latina o las ciudades intermedias, en algunos países, donde las ciudades intermedias son pujantes, no puedes pretender que la gente sea como un emprendedor social y con eso salga adelante, porque una de las cosas más importantes de la región es que la educación, si alguna vez fue, ha dejado de ser esa palanca de crecimiento económico. Ha dejado de ser, en la mayoría de casos, los jóvenes ven que si van a la universidad se endeudan en carreras que ya no tienen mucha salida. El COVID yo creo que fue feroz en demostrar en América Latina, pues, la poca integración de la educación. Entonces en muchos casos la gente entra por la informalidad para salir adelante, para sobrevivir. Informalidad en la venta de arepas, informalidad en la venta de anticuchos, informalidad en la peluquería, en una serie de cosas de gente que probablemente debería estar recibiendo subsidio al desempleo, pensiones dignas. Digo, no vamos a entrar en ese capítulo. Que es el capítulo del Estado que sí realmente no existe. Entonces el tema es que muchos de esos informales hoy día son cooptados, por ejemplo, con los préstamos extorsivos. Entonces tú pones tu pequeña peluquería, eres migrante irregular de cualquiera de nuestros países, inmediatamente viene una banda y te dice yo te presto plata para que tu peluquería funcione y a la siguiente vez te quitan la peluquería entera, o te amenazan, o te hacen vender drogas, digamos, esos son, parece que son pues este guiones de Netflix, pero la verdad es que una y otra vez uno se encuentra con la misma situación en muchas partes de la región. Entonces eso también, pues, hay que tomarlo en cuenta, porque el gran problema que tenemos hoy, yo creo que es el gran desafío, es cómo hacer para que la Cumbre de las Américas, en las reuniones de los presidentes, que ahora estamos todos muy preocupados por el crimen organizado, volvamos a recuperar la preocupación por esta otra parte. Hay que ser muy, muy ágiles, muy castigadores, etcétera contra el crimen organizado y los mercados ilegales, las estructuras, etcétera. Pero luego también no podemos dejar de ver que somos un continente que nuestras repúblicas se formaron para que haya un porcentaje menor de gente incluida, legal, ciudadanos. Y todos los otros ya vean, ya vean si en la informalidad o en la ilegalidad, cómo puedan. Seguimos así, seguimos así, salvo algunos países que están más institucionalizados, tal vez Uruguay, ¿cierto? Argentina fue así por muchos años, pero la gran mayoría de países, pues, los latinoamericanos sobrevivimos muchas veces a costa del Estado y en otras ocasiones digamos con mucho emprendedurismo que, de una informalidad que hoy día y después del COVID se ha consolidado, pero que yo creo que está cada día más enfrentada también a la amenaza de la de la violencia de los mercados ilegales.

Eliezer: La militarización, el encarcelamiento masivo, la represión sigue siendo la respuesta natural frente al crimen, ¿no? A pesar de que repetidamente ha mostrado sus fracasos, ¿por qué sigue siendo la fórmula dominante?

Lucia: Bueno, porque es una respuesta expresiva, ¿no? O sea, la gente si ve militares en la calle y antes no veía nada, veía tres chicos que le cobraban por salir de la puerta de su casa. Y creo que para mucha gente que vive en condiciones de mucha inseguridad, pues, eso le parece bien, así sea que sean violentos. Todo lo otro no importa tanto. Yo sí creo que además el temor es un fenómeno social en sí mismo.

Entonces el temor tiene que ser enfrentado también, pues, con políticas públicas particulares. Tal vez no el encerramiento masivo, realmente la gente ni lo ve, ¿no? Salvo pues en lugares extremos como El Salvador, claro, en otros países tú puedes decir oye, he aumentado al doble la cantidad de presos y tu dices: qué raro, porque yo en mi barrio sigo viendo lo mismo. Pero lo que sí es cierto es que necesitamos revisar qué pasa con las policías, que todavía partes importantísimas, incluso en las ciudades capitales no tienen cobertura de patrullaje. Entonces, tú estás siendo víctima de violación de, ya ni siquiera vamos a entrar en los mercados ilegales. Y bueno, no sé con quién te arreglas porque la policía nunca llegó a tu barrio ¿no? Nunca la viste. Entonces, ante eso, yo creo que quiero como alejarme de la posición, que a veces hemos tenido, decir: bueno, la militarización es muy mala, no sirve para nada. No, a alguna gente la tranquiliza y lamentablemente la tranquiliza porque no hemos sido capaces de generar otra cosa, ¿no? Que es una presencia de otro tipo de Estado. Pero en el largo plazo es un sistema que lo que hace es nos mete en un loop donde luego uno dice bueno, entonces ahora necesito drones y ahora necesito aviones no tripulados. Y la solución es la lectura facial de personas que van caminando por la calle

Ya eso es un loop que nos lleva directamente, digamos, a un camino sin retorno. Pero yo ahí te diría que yo no le pongo la responsabilidad al ciudadano, le pongo la responsabilidad al político, que sabe que no sirve y que igual va y te sugiere. ¿Por qué no hacemos 150.000 nuevas cárceles? Tú le dices pero ¿es posible construir esas cárceles? Bueno, no, pero… ¿si me entiendes? Por eso es que creo que es muy importante cuando uno reconoce que la seguridad es electoralmente muy lucrativa y que a veces más que fact checking, lo que hay que empezar a preguntarle a los candidatos es bueno ¿cómo vas a hacer eso que propones hacer? Porque nos hemos quedado en los 140 caracteres de quiero leyes más duras. Bueno, las leyes que tenemos casi en toda la región son durísimas, ¿no? Quiero más cárceles. Ok, ¿cómo las vas a construir? ¿En dónde? Si realmente tenemos un problema muy serio de capacidad de construcción. Entonces ahí yo sí creo que pues para el ciudadano latinoamericano que ve a sus políticos decir que la crisis de seguridad es total y que no hay solución más allá del militarismo o el castigo, no les podemos pedir que ellos hagan una reflexión del estilo perdón, están equivocados, en realidad lo que hay que hacer es prevención del delito, ¿no? Y por eso es que creo que también en el mundo progresista es muy importante, una recapitulación de lo que ha pasado, porque el mundo progresista es el que tenía… y no solamente el mundo progresista, el gobierno de Sebastián Piñera en Chile, pues fue un gobierno que ponía mucho énfasis, por ejemplo, en el tema preventivo, ¿no? Existía una política nacional de prevención, pero como que esa ola desapareció y bueno… Y que mantenga pues el populismo punitivo ha arrasado.

Eliezer: ¿Qué tipo de políticas públicas podrían realmente reducir el poder ilegal? No pretendo que nos digas una solución así, pero recién, por ejemplo, decías una cosa que a mí me parece muy buena es el temor…O sea, una cosa es la violencia y el crimen y otra cosa es el temor. Y eso es un fenómeno social en sí mismo y hay que trabajarlo, ¿no? Y recién, por ejemplo, estabas diciendo bueno, no, desde el principio lo dices, han desaparecido las políticas preventivas.

Lucia: Claro, o sea, todavía tenemos que hacernos cargo. O sea, se va a vender droga donde se consume droga y tenemos que hacernos cargo, que en América Latina hay un consumo importante de drogas, que va a sostener la presencia de los mercados ilegales y las estructuras criminales. Entonces, de ahí a saltar a la descriminalización, yo creo que ese es un camino largo. Yo no pondría el eje de la conversación en la descriminalización, porque ahí nos vamos a matar todos, pero tal vez sí podríamos poner el eje en cuánta plata más vamos a invertir, en que no solamente los ricos se salven de la adicción en América Latina, porque verdaderamente si tú no eres rico, pues morirás adicto en la calle ¿no? Porque hay muy poquita oferta pública para ese tipo de problemas. Y si tú le a eso lo intersecciona con problemas de salud mental, ¿no? Salud mental más consumo problemático, más haber sido víctima de violencia. Bueno, para ese grupo de la población, que es probablemente el grupo que por muy poquita plata va a ir a matar a alguien, casi no hay oferta pública. Entonces creo que estamos en un momento donde tendríamos que ser proactivos y también creativos en programas que nos puedan ayudar, resolver, tener un Estado que esté más presente, una población que está, bueno, sufriendo muchas, muchos problemas que los pueden llevar, digamos, a ser víctimas de la violencia o victimarios.

Eliezer: Lucía, después de tantos años de violencia e impunidad, ¿dónde ves las posibilidades de cambio? ¿Dónde ves la esperanza?

Lucía: Hay una serie de iniciativas, incluso en Brasil, que han sido muy exitosas. ¿Pero cuál es el problema que tienen esas iniciativas? Tres: Uno, muy poca plata; dos, voluntad política bajita para mantenerlo cuando el que lo hizo fue el anterior líder. Entonces, realmente programas importantes que iban teniendo resultados, hay un cambio de gobierno y los matan ¿no? Porque pues mejor creo yo, mi propio programa con mi nombre y cosas de ese estilo; y el tercero es, digamos, una búsqueda de inmediatez en el resultado político electoral. Entonces, por supuesto que es mucho más rendidor electoralmente comprar mil vehículos policiales.

¿Sin duda no? Pero, creo que estas iniciativas que muchas veces han tenido el apoyo internacional,incluso en países muy enfrentados con problemas de violencia, que lo que uno tendría que tener es la voluntad política, el diseño transversal, la paciencia política, digamos, para encontrar los resultados, y de eso pues hemos visto poquito. Ahora, el fenómeno está complejizándose no solamente en la región y por ende también yo creo que va a haber o debería de haber una preocupación y una vocación política más transversal para hacernos cargo de esto más seriamente, ¿no? Ojalá.

Eliezer: Lucía, muchas gracias por tu tiempo.

Lucía: No, gracias a ustedes.

Jesús Delgadillo: Este episodio fue producido por mí, Jesús Delgadillo. Lo editaron Silvia y Eliezer. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido es de Elías González, con música de él y de Remy Lozano.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Franklin Villavicencio, Lisa Cerda, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Elsa Liliana Ulloa y Daniel Alarcón. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Eliezer Budasoff: El hilo is funded thanks to the support of its listeners and various organizations, including Grupo SURA, an investment manager focused on financial services. SURA promotes independent journalism that strengthens democracy in Latin America and contributes to a better-informed citizenry.

Silvia Viñas: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: And I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Eliezer Budasoff: In recent decades, organized crime in Latin America has mutated from a collection of bands and gangs into numerous organizations capable of altering the political and social order of entire countries.

Archive audio, BBC Mundo: The Tren de Aragua is one of the most feared criminal gangs in Venezuela.

Archive audio, El País: And the PCC is Brazil’s most powerful criminal organization.

Archive audio, DW Español: The government blamed the bloodshed on gangs, especially Mara Salvatrucha or MS-13. The government categorizes them as terrorist groups.

Archive audio, Grupo Reforma: Members of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel boasted that they are well-armed and armored.

Eliezer: In the most common narrative constructed by the media and popular culture, these criminal organizations appear as a large mafia network that operates on a continental scale and engages in drug trafficking, kidnapping, and extortion.

Silvia: But the reality is much more complex. Behind their names and acronyms lie fragmented and flexible structures that also control mining, fuel theft, smuggling, human trafficking, and other crimes.

Eliezer: This range of activities moves millions of dollars throughout the region while consolidating power. An illegal power that permeates everything, from daily life to the economy and politics.

Silvia: Today, what does it mean to talk about “illegal power” in Latin America, and what does it reveal about the failure of states in the face of crime and inequality?

It’s January 16, 2026.

Silvia: To understand how “illegal power” works in Latin America, we spoke with Lucía Dammert, a Chilean-Peruvian sociologist, teacher, and researcher. Lucía has been a specialist in security issues for 30 years. In September of last year, she published a book titled Anatomía del poder ilegal (Anatomy of Illegal Power), where she makes a key distinction for examining criminal dynamics in the region.

Lucía: I didn’t want to write another book about criminal structures, because I think that… It’s very important, but it’s less substantial than what’s happening in the region. And I feel that illegal power is the conjunction of exponential growth in illegal markets with a gigantic, fierce capacity for political-institutional corruption that in most Latin American countries enters from the local level, let’s say, from local governments upward. But there are quite a few presidents who have been imprisoned for money laundering in Latin America, right? And in parallel, there’s an atomization and a very great weakness of the state’s oversight apparatus and, of course, political parties. So illegal power is established in those places where you have illegal markets, very high levels of corruption, and very low state capacity. So, from the many interviews I conducted in Latin America, for many of them, even their elected mayor represents illegal power, because later he goes to prison for corruption, because people don’t really understand why, because he has family members who are in organizations, let’s say, in illegal markets. So there’s a relativization of what legal power is and there’s an exaltation of that illegal power that, moreover, often helps people in a much more direct way.

Eliezer: Can you tell us a bit about what the most relevant illegal markets in Latin America are today?

Lucía: Yes, look, there’s everything, but I’d say there are four that need a lot of emphasis. One is illegal gold mining, which is highly concentrated in Colombia, Peru, Brazil, now Venezuela too, and a little bit in Bolivia. Almost all Amazonian countries. And this has many consequences, right? A big problem—it’s estimated that between 70 and 80% of the gold we extract has an illegal origin, and I say has an origin because later, through various mechanisms that are easy to identify in these countries, it becomes legal. But well, it’s a bit difficult to get the political will to fight against this, right? I think the Peruvian case is very evident, but then this is generating deforestation in the Amazon, this is generating river contamination, it’s generating the killing of human rights defenders in the Amazon. I believe the Amazon is a space that is being massively violated.

Then you have human trafficking, especially of women, for sexual and labor exploitation, which is one of the largest illegal markets in the world, and in Latin America it moves a lot of money. It’s estimated at more than 12 billion dollars a year, right? It’s also an internal and external market. There are people, there are women who are kidnapped within the same country, right? Moreover, well, because of the machismo and patriarchy in our countries, it’s often not even priority number one. Sometimes, many trafficked women are found by the police and then expelled as irregular migrants when they are victims. I think there’s also an important phenomenon there. A third element, undoubtedly, is human smuggling, right? The smuggling of migrants, where the main difference is—for those who are listening—migrants are taken and left in another country. It’s not that smugglers keep them for exploitation, but they move them. But that movement is a violent, terrifying movement that takes advantage of people’s vulnerabilities. And also, well, an important part of the millions of Venezuelans who have migrated must have moved through these networks, right? And they are super lucrative networks, with a fierce capacity for flexibility in terms of routes. But also, no one can say that 3 million people moved and no public official saw them pass through their countries. I mean, that’s the biggest demonstration that here you have spaces of corruption—I’m not saying transnational, but at least in many places, right? And well, it seems that we’ve been too focused on the drug issue and the others haven’t been seen much.

I also think, let’s say that the issue… Obviously the logging issue is an important issue, and the two enablers of these phenomena that we shouldn’t forget: one is arms trafficking, right? Which is fierce, which generally comes from legal weapons, because there are no illegal weapons factories, let’s say, but rather there are factories that make weapons and then the trafficking is illegal. And on the other hand, money laundering, right? Because what these illegal markets want is to legalize their money. They do want to buy a house, they do want to buy a car. It’s not that they want to keep the money under the mattress or spend it on small parties, right? Sometimes the iconography makes us think that these are those small-time narcos who want to throw a party, right? So for money laundering we’ve also been, let’s say, we continue to be very inefficient.

Eliezer: What kind of other actors are involved? I don’t know—companies, local elites…

Lucía: Of course. Well, small and medium-sized companies. The financial system to start with. All those places where you have a lot of physical cash—there you have to keep an eye on them, you have to keep an eye on casinos. Well, not to mention the huge chapter of real estate, right? All the apartment sales that are paid for in cash because there’s an exchange control or any other phenomenon. I mean, every time we have an abnormal transaction, let’s say, we should be filing a report, and I feel that Latin America has made strides in this, but not enough. And especially the political will to audit these reports is very low. Why? Because let’s say that the real estate broker is your uncle’s friend. Or it’s your cousin. Or whoever, right? I mean, it’s very… Online casinos, right? Digital betting houses—the levels of regulation don’t exist. We have a very serious problem there, right? Or women who sell hours on the internet. I mean, there’s a series of markets, but we also have today, well, illegal cigarette smuggling markets, illegal copper theft markets, salmon theft, gold markets. Well, there’s everything, right? Every product that one can normally sell will have its mirror, which is the illegal mirror. Because some don’t want to pay taxes and because sometimes it works better. But we’ve effectively been letting these little monsters grow that we thought were controlled, and they’ve been consolidating territorial powers, they’ve been consolidating international links, and well, they have fierce consequences in social, political, and economic terms. Especially because many times their small bands, tiny ones, that are in the business of moving people, for example—when they’re not paid, what do those bands do? Extortion. So, that generates what I think is the most complex circle, which is that then they start extorting you for your day-to-day life, the ordinary citizens of the region, especially the poorest. Extortion is a crime mainly against the poorest population of the region, who are desperately looking for some kind of magic recipe, right?

Eliezer: When people talk about organized crime in Latin America, specifically large groups, right? Like the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, the Tren de Aragua, Comando Vermelho, Mara Salvatrucha—they’re usually presented as international networks or articulated gangs. In practice, is this the case?

Lucía: Yes, look, I think there are two things to keep in mind. One, you have articulated illegal markets in the region. Those illegal economies of gold, the illegal drug economy, human trafficking. The end is articulated not only regionally but globally. And then you have the criminal structures that are organized around those markets, and those structures—well, you have some very large ones in Latin America, without a doubt, like the Gulf Clan, without a doubt Sinaloa, the PCC, probably the Tren de Aragua. But above all what you have is a much more flexible system, much more, let’s say, granular, with many intermediate and small organizations that come into contact—a less organized contact than what you see in narco series when you see a big boss, right? So it seems very important to me to make the separation between the illegal market and the criminal structure, because then when you say who are we fighting against? You say we’re going to fight against the criminal structure and the market continues to flourish with other structures.

Eliezer: One of the things we wanted to try to understand with you is—there’s a lot of talk about the big names of the gangs, right? A narrative and a myth are being built, and at some point we wondered, is it really distributed in large criminal blocks or is it rather multiple local groups with their own dynamics?

Lucía: Yes, I think there’s everything, right? Because in Latin America you have countries where illegal markets have levels of territorial, political, economic, social control much, much broader than others. Well, the Gulf Clan even has a political structure, the PCC in Brazil. But then, for example, the Tren de Aragua seems to me an interesting structure. First because you have a giant migration of Venezuelans through Latin America, some of them engage in criminal actions, but not for that reason every time you arrest someone who is of Venezuelan origin does it mean that the Tren de Aragua is present. What’s happening today in the region? The headlines say, “Tren de Aragua dismantled in Colombia, Tren de Aragua dismantled in Peru, Tren de Aragua dismantled in Chile.” And you say, well, but this is bigger than Coca-Cola, right?

And in reality we have to realize that these are structures that can call themselves part of the Tren de Aragua, that may be linked with some of the businesses or illegal markets that the Train does move, which is mainly the issue of human trafficking. But that doesn’t mean that one has, in quotes, dismantled the Tren de Aragua, but rather dismantled maybe one cell of the many that exist in a country dealing with that market. This is fundamental because for many years it’s happened to us that we measure the police and the exercise of power by the number of high-level people they arrest. So obviously no one wants to say, “Well, we arrested five traffickers,” but rather than “the main cell,” and that has led us to divert our attention from the central problem, which I think is the problem of the markets, where the money is, where politics gets corrupted, where territorial control is achieved. And of course, this doesn’t diminish the importance of the levels of violence, of the stronger organizations, but rather what it shows you is a much more complex criminal kaleidoscope in the region.

Eliezer: In recent years, for example, a kind of mythology of organized crime has been consolidated. There are leaders who present themselves as strategists, vigilantes, or benefactors. How do the media and popular culture contribute to building this image of “the powerful criminal”?

Lucia: Look, it’s very interesting. Well, with the media issue you give me the opportunity to say something that I think is fundamental, which is that if there’s anyone who really knows what’s happening in the region today, it’s investigative journalism. Most academics, what we manage to reach are the more accessible levels of what the illegal markets are, right? You see many studies that are kind of concentrated on street gangs, on medium-level producers. But when you see the work that very serious investigative journalism does in Latin America, well, they’re in the territories, they’re there for weeks, they have a very important level of granularity. So that’s also why so many investigative journalists have been killed. Knowing this from the capital cities is impossible. So that’s one part. The other part is a bit the search for spectacle—that there are very violent crimes, that violence has increased in countries where there wasn’t so much violence before, like Uruguay, Chile, Costa Rica. That there’s a democratization, in quotes, of illegal markets in almost the entire region. That today the phenomenon of extortion is not a Colombian or Mexican phenomenon, but is a transversal phenomenon. And that for the media, the temptation of the bloody headline that ultimately also mixes a lot with the crisis of traditional media outlets that are in the battle for clickbait, let’s say. If they don’t put a bloody headline, no one is going to go read a story that says, well, they arrested five criminals. No one is going to click to look at it on social media, which is where we’re finding out about everything today. So it’s an ultra-vicious circle. Also, let’s say, part of the phenomenon we’re dealing with is that this sensationalization of violence, this normalization of everyday violence, etc., also brings great frustration on the part of citizens who see that the state doesn’t respond, that problems aren’t solved. And of course, they’re terrified, right?

Eliezer: This terror, let’s say, and this narrative—what effect has it had in electoral terms and for democracy in the region?

Lucía: Security is a big business for criminals, but it’s also a big electoral business, right? Unfortunately, not just now. For many years, security was what allowed differentiating left from right, right? So, the left said wages, protection, etc., and the right said no, here we need more control, there’s a security problem, right? Well, poor youth, anyway. And now the left has been left without its social protection part and what we’re already in is a very generalized situation, where the natural discourse of everyone, left and right, is that the problem is this enemy, let’s say, narco-terrorist or well, anyway, mainly foreign. It’s very interesting how in the region the concept of prevention has practically disappeared in almost all countries, right? Or the concept of post-prison rehabilitation. So, people have every right to feel anguished because what they see is that nobody protects them.

What they see is that when they report, the police don’t arrive. That when the police take someone away, then that someone returns and one ends up being a victim. With the increase in extortion, people no longer just have the impression that they might be victims, but they know that their daily life is being confronted by small or medium-sized structures, but that still impacts their lives. And what they want is answers. And we’ve been very incapable in the region of having sustainable, lasting, long-term responses that show results. There have been interesting things, yes, but politically they’ve been changed. Well, so at the end of the day, citizens value the hard hand, punishment, repression, even things that citizens know aren’t going to work, like the death penalty, for example. But the feeling that you’re going to have someone tough.

Lucía says that this is not a recent phenomenon, that even in the era when there was a left-wing hegemony in the region, some governments began to incorporate ex-military personnel into their cabinets to give an image of firmness.

Lucía: And that generates electoral gain. Well, we see it in the case today in Latin America, in the elections. There was a moment, about six months ago, where they said they wanted a Bukele. Now that they’ve realized that the Bukele phenomenon brings negotiation with gangs and brings extrajudicial killings, etc., some have stopped asking for a Bukele. But the recipe is a very similar recipe, and my impression is that the damage done to democracy is gigantic. But we also have to take responsibility that the political parties that recognize the need for democracy have done very little to make citizens happy and fulfilled, or at least feel that there’s an effort, right? I think citizens are rightfully very upset.

Eliezer: Well, one of the reasons we wanted to talk to you was the recent massacre carried out by the Rio de Janeiro police in the favelas.

Silvia: In October 2025, a few weeks before we interviewed Lucía, a mega police operation in Rio de Janeiro left more than a hundred dead and became the deadliest in Brazil’s history.

Archive audio, France24: Dozens dead, barricades and fires in a mega anti-drug operation in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. More than 2,500 agents, armored vehicles and helicopters participated in the raid against the criminal group known as Comando Vermelho, or Red Command, one of the most powerful in Brazil.

Eliezer: Then some polls came out about what people’s opinion was on the matter, and the highest approval rate—it was very high—was in the favelas.

Lucía: Well, I’m not surprised. Why? Because in this new criminal order in Latin America, where at the local level there’s not so much robbery anymore. There is, but there’s not so much cell phone robbery or car theft, but what there is is extortion. Extortion to enter your house, extortion to leave your house, extortion to go to school, extortion to drive your taxi. People are living under very terrible conditions sometimes. Extortion is, I think, probably the most complicated criminal element today in the region, because when extortion arrives it’s very difficult to remove it, because it’s a way of making money quickly, totally with impunity. So you see, in the most popular sectors, a much harder view, right? You see it in the elections—the votes for the right, ultra-right, the hardest, are very much in the popular sectors that are asking, crying out, for someone to please solve their problem. And it becomes a form of social relationship. So I understand that even what happened in Rio, which is dramatic, because apparently there was an extrajudicial killing, a very large one. As they’re young people who are recognized as part of a gang, right, or a criminal group, well, citizens feel that at least something is happening. It’s about time.

And this leads us to a discussion that I think we also have to understand, which is that in many spaces of Latin American life, the concept of human rights is being redefined, and we specialists sometimes don’t see it. We continue with the discussion of human rights post-dictatorships, post-civil wars, and in reality for many Latin Americans today the conversation is different.

Silvia: The police operation in Rio de Janeiro on October 28 aimed to capture the high-ranking leaders of Comando Vermelho, but that didn’t happen. More than 100 people ended up dead. Organizations like Amnesty International and the Latin American Council of Social Sciences categorized the event as a massacre and another example of systemic violence.

Eliezer: In a Senate hearing, the undersecretary of intelligence of the military police of Rio declared that the raid had an “insignificant” impact. Favela residents said the operation did little to stop the violence and territorial control.

We’re taking a break and we’ll be right back.

Silvia: We’re back on El hilo.

Eliezer: What does it mean to talk about criminal governance? In what way does organized crime participate in or substitute state functions?

Lucia: Yes. Look, for many years we had the idea that where the state wasn’t present, criminals took charge, right? I think that happens less in the region today, because the state is almost everywhere. What happens is that the state has an ambivalent relationship with illegal economies. In some cases they administer them, in other cases they look the other way, right? In other cases they’re directly part of it. What you see at the local level—you have, I don’t know, criminal groups of 100 people and five policemen and one prosecutor and two logging inspectors who see the boats pass by and they tell you, “Well, I really don’t know what to do here because I have a boat that’s almost like a rowboat, right?” So the difference is gigantic. Now I think that moves us away from the concept of fragile state, right? That was used for a long time, fragile state or state, well, directly absent.

Eliezer: Absent.

Lucia: Of course, because in reality in many countries the state is there, but it’s fulfilling other functions, it’s looking at other things. And what I think, and well, many Latin American authors as well, but above all based very much on what investigative journalism does, I’d say, is that the state begins to benefit from illegal economies. So, there are quite a few governors in many countries who tell you, “Well, smuggling is still a form of subsistence.” You say, “Well, smuggling, maybe.” But at the end of the day, they’re smuggling people, children, and kidneys. I mean, the system has multiplied. So, I think yes, it’s something we have to look at with great danger. Because it’s very difficult when a mafia state is already constituted. When it’s already constituted, let’s say, illegal power comes to have a more important role. Then, who can we citizens really ask for justice, peace, right?

So in some countries I think this is much more advanced. It seems to me that in the Mexican case, which is a case that has many more years of deterioration due to its proximity to the United States, well, it’s very interesting that it turns out all the cocaine is sold there, but we’re the narcos on this side. The conversation is very strange, it’s very strange. Everything that’s happening to us is very strange. But of course in Mexico there are, in addition to these phenomena of illegal markets, as in other countries, small colonies, neighborhoods, entire neighborhoods where the government is established by these medium, small, and large organizations. In the Mexican case it’s much more evident because the weapons capacity is very strong and because the market is gigantic. When you look at what, let’s forget cocaine now, let’s say the theft of gasoline and oil from Pemex, that’s a multimillion-dollar market. So you say, OK, well, that’s a multimillion-dollar market, there are many structures. Where is that profit being invested again? And I think that’s where we are—at just the right moment to ask ourselves those questions before the situation can get worse.

Eliezer: Besides, what you were saying about Mexico—everything that emerges as a problem whose solution costs money is a business that ends up being permeated by organized crime, right? You were talking about the multimillion-dollar huachicol business of Pemex fuel, but water, right? When there are water problems and the water trucks, right? And I really like what you’re saying about when we think the state is weak or the state is absent—in reality it’s not that it’s absent, it’s present in a very particular way.

Lucia: Of course, with a certain level of ambivalence, right? Because you could say, hey, it’s not that the state has zones where there’s no education, no health. It’s not that there are no roads, no social housing. The state is present, but of course, what has been lacking in many cases is police capacity, justice, right? But of course, again, justice, police, and prison aren’t going to solve this phenomenon. They’ll solve some phenomenon. Of course, you need better police, and nothing like Mexico recognizes that good police would help you, let’s say, solve other phenomena. Because there’s also something that’s very important in the region, which is that almost half of all… we’ve already seen the typical data, right? That we represent 8% of the population and 30% of the world’s homicides. But half of those homicides are people killing each other with their neighbors, people killing their relatives. I mean, it’s not that 100% is linked to organized crime. Yes, we also have a very strong violence problem, and that violence problem, since we’re so hyper-concentrated on some more organized criminal phenomena, sometimes we’ve set it aside. And that also requires, let’s say, to be looked at, right? It’s a difficult kaleidoscope. Now, of course, one thing is Mexico, which is a large country, a rich country. And another thing is what’s happening in Haiti, right? That in Haiti, we really couldn’t talk about a state structure anymore, but rather about the remnants of what state capacity is, the remnants of what the rule of law is. And Latin America watches absorbed, and the whole world watches absorbed what’s happening there, right?

Eliezer: Why is it so difficult to break this type of link, this coexistence of negotiation between state actors and criminal actors, even in consolidated democracies?

Lucía: I mean, well, the problem—look, if we follow the line of understanding this as illegal markets, illicit economies that generate hundreds of millions of dollars in the region, the question that comes next is: where is that money? And that money is not in the hands of practically any of the prisoners in Latin America. Not one. Latin American prisoners are poor men, illiterate, with consumption problems, mainly. So, what happens is that it’s been very easy for criminal justice systems and for politics to concentrate on indicators of seizures, arrests. To say, well, I’ve bought a thousand vehicles, because ultimately saying, for example, that there are money laundering problems, that there are entire regional economies that are sustained by money that is illegal, that there are political parties that are financed by criminal organizations, is very difficult to sustain in the medium and long term in many countries. So, this is a rope that has turned toward, in quotes, the easiest thing, which is to look for a threat that for many years—look, I’ve been working on this for 30 years now—but for many years the threat was the young poor person, right?

All the images were of poor young people, who are the ones who are going to rob you. They’re going to rape you, anyway. But that threat we’ve now transformed into an international terrorist threat, which is mainly foreign groups, right? That is linked with some of these gigantic criminal structures. And that allows us, in quotes, in some countries to forget about the hundreds of thousands of young people without education, without work, without, well, all the underlying problems that exist, who are the soldiers that strengthen that army of the illegal market, right? And what it does is concentrate us on the more international responses, if you will, or the more control and justice responses. So, there’s a trap there that we have to get out of. Because the truth is that if we look at the market issue, most countries have had very few results in the fight against money laundering, controlling the entry of weapons, and that, well… Not to mention illegal mining, drug sales, etc.

Silvia: We’re taking one last break and we’ll be right back.

Silvia: We’re back.

Eliezer: I’d like to put in its proper place this idea that, on the one hand, criminal structures are a mode of social advancement for people who are on the geographic and social margins. But on the other hand, how much choice is there in what they do?

Lucia: Well, when you leave the capital cities—because when you leave the capital cities of Latin America or the intermediate cities, in some countries where intermediate cities are thriving—you can’t expect people to be like a social entrepreneur and get ahead with that, because one of the most important things in the region is that education, if it ever was, has ceased to be that lever of economic growth. It has ceased to be, in most cases—young people see that if they go to university they get into debt for careers that no longer have much of a future. COVID, I think, was fierce in demonstrating in Latin America the poor integration of education. So in many cases people enter through informality to get ahead, to survive. Informality in selling arepas, informality in selling anticuchos, informality in the hair salon, in a series of things—people who probably should be receiving unemployment subsidies, decent pensions. I mean, we’re not going to get into that chapter. Which is the chapter of the state that really doesn’t exist. So the issue is that many of those informal workers today are co-opted, for example, with extortionate loans. So you set up your small hair salon, you’re an irregular migrant from any of our countries, immediately a gang comes and tells you, “I’ll lend you money so your hair salon works,” and the next time they take your entire hair salon, or they threaten you, or they make you sell drugs. I mean, these seem like Netflix scripts, but the truth is that time and again you encounter the same situation in many parts of the region. So that also has to be taken into account, because the big problem we have today, I think it’s the big challenge, is how to make it so that the Summit of the Americas, in the meetings of presidents, now that we’re all very worried about organized crime, we recover concern for this other part. You have to be very, very agile, very punishing, etc., against organized crime and illegal markets, the structures, etc. But then we also can’t fail to see that we’re a continent where our republics were formed so that there would be a smaller percentage of included people, legal, citizens. And all the others, you’ll see, you’ll see if in informality or in illegality, however you can. We continue like this, we continue like this, except for some countries that are more institutionalized, maybe Uruguay, right? Argentina was like that for many years, but the vast majority of countries—well, we Latin Americans often survive at the expense of the state and on other occasions, let’s say, with a lot of entrepreneurship that comes from an informality that today and after COVID has been consolidated, but that I think is increasingly confronted also by the threat of violence from illegal markets.

Eliezer: Militarization, mass incarceration, repression continue to be the natural response to crime, right? Despite having repeatedly shown its failures, why does it continue to be the dominant formula?

Lucia: Well, because it’s an expressive response, right? I mean, people see military personnel on the street and they didn’t see anything before—they saw three guys who charged them to leave the door of their house. And I think for many people living in conditions of great insecurity, well, that seems fine to them, even if they’re violent. Everything else doesn’t matter as much. I do think that fear is a social phenomenon in itself.

So fear has to be confronted as well, with particular public policies. Maybe not mass imprisonment—people don’t really see it, right? Except in extreme places like El Salvador. Of course, in other countries you can say, “Hey, I’ve doubled the number of prisoners,” and you say, “How strange, because in my neighborhood I still see the same thing.” But what is true is that we need to review what’s happening with the police, because still very important parts, even in capital cities, don’t have patrol coverage. So, you’re being victimized, and let’s not even get into illegal markets. And well, I don’t know who you’re going to work it out with because the police never came to your neighborhood, right? You never saw them. So, faced with that, I think I want to distance myself from the position that we’ve sometimes had, saying: “Well, militarization is very bad, it’s useless.” No, it reassures some people, and unfortunately it reassures them because we haven’t been able to generate something else, right? Which is a presence of another type of state. But in the long term it’s a system that puts us in a loop where then you say, “Well, now I need drones and now I need unmanned aircraft. And the solution is facial recognition of people walking down the street.”

That’s already a loop that takes us directly down a path of no return. But there I’d say that I don’t place the responsibility on the citizens. I place the responsibility on the politician, who knows it doesn’t work and still goes and suggests it to you. “Why don’t we build 150,000 new prisons?” You say, “But is it possible to build those prisons?” “Well, no, but…” You know what I mean? That’s why I think it’s very important when one recognizes that security is electorally very lucrative and that sometimes more than fact-checking, what we have to start asking candidates is, “Well, how are you going to do what you’re proposing to do?” Because we’ve stayed at the 140 characters of “I want tougher laws.” Well, the laws we have in almost the entire region are very tough, right? “I want more prisons.” OK, how are you going to build them? Where? We really have a very serious construction capacity problem. So there I do think that for the Latin American citizen who sees their politicians say that the security crisis is total and that there’s no solution beyond militarism or punishment, we can’t ask them to reflect and say, “Sorry, you’re wrong. Actually what needs to be done is crime prevention,” right? And that’s why I think that in the progressive world it’s also very important to recapitulate what has happened, because the progressive world is the one that had… and not only the progressive world—Sebastián Piñera’s government in Chile was a government that put a lot of emphasis, for example, on prevention, right? There was a national prevention policy, but it’s like that wave disappeared and, well, punitive populism has swept through.

Eliezer: What kind of public policies could really reduce illegal power? I’m not asking you to give us a solution like that, but just now, for example, you were saying something that seems very good to me—fear. I mean, one thing is violence and crime, and another thing is fear. And that’s a social phenomenon in itself and you have to work on it, right? And just now, for example, you were saying, “Well, no, from the beginning you say it, preventive policies have disappeared.”