Amparo Marroquín

Donald Trump

Migración

Deportaciones

Migrantes

Estados Unidos

Desde su retorno a la Casa Blanca, Donald Trump ha puesto en escena una crueldad deliberada contra los migrantes que va más allá de las políticas de mano dura: desde enviar gente a cárceles infames en otros países sin ninguna prueba hasta deportar a chicos con cáncer o publicar caricaturas de personas siendo detenidas. Ahora, ¿cómo es posible tratarlos como si todos fueran una amenaza y sus vidas no tuvieran ningún valor en una sociedad donde viven unos 50 millones de inmigrantes? En este episodio hablamos con la profesora salvadoreña Amparo Marroquín, que ha investigado durante dos décadas los procesos de migración entre Centroamérica y Estados Unidos, para entender cómo y cuándo se han construido los principales imaginarios y estereotipos sobre los migrantes que dominan hoy la narrativa oficial estadounidense.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Eliezer Budasoff -

Edición

Silvia Viñas, Daniel Alarcón -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción en redes sociales

Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Elías González -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

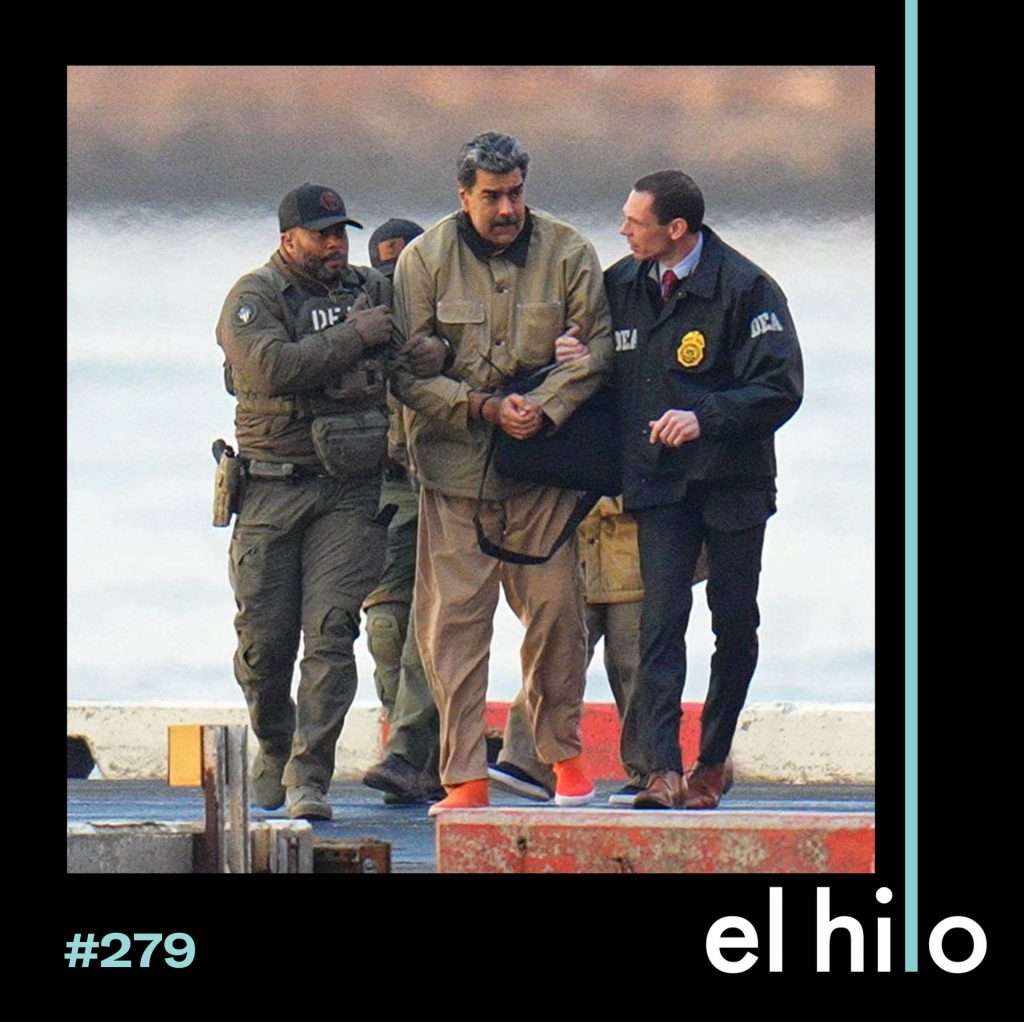

Fotografía

Getty Images / Matt McClain

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Eliezer Budasoff: Antes de empezar, queremos recordarte que estamos en nuestra campaña de financiamiento y quiero pedir tu apoyo. Somos un medio sin ánimo de lucro, y nuestra permanencia depende de oyentes como tú. Cada historia que producimos se logra con un respeto profundo por los hechos, por el relato de los protagonistas y los expertos, y por nuestros oyentes.

Silvia Viñas: Y en un mundo cada vez más polarizado, es más difícil distinguir entre el periodismo y la desinformación. Medios como el nuestro tienen más valor que nunca. Pero no podemos hacerlo solos. Si aún no has donado o tienes la posibilidad de ayudarnos con un monto adicional, considera por favor hacerlo hoy. Únete a Deambulantes, nuestro programa de membresías. Puedes donar desde un dólar. Cualquier aporte suma. Ve a elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos a seguir explicando América Latina. ¡Gracias desde ya!

Audio de archivo, testimonio: El racismo está a flor de piel ahorita, y ya nomás lo hacen porque eres hispano. Ni siquiera se fijan si tienes documentos.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: La estudiante de doctorado de Tufts fue arrestada caminando por la calle cerca del campus universitario. Agentes encubiertos la emboscaron. Luego aparecen otras cinco personas, todas con máscaras, y le informan de que son oficiales de la policía.

Audio de archivo, reportaje:

Presentador: Cómo explicarle a una niña de 5 años y a su hermano de 11, que su padre fue detenido por ICE frente a ellos.

Niño: El policía lo agarró y lo jaló, y lo sacó a la fuerza. Y después… lo esposaron, y le lastimaron su mano.

Audio de archivo, presentador: No es la primera vez que desde Estados Unidos se burlan de los migrantes. Pero lo que pasó esta vez rebasó los límites…

Silvia: Es difícil decir a esta altura qué cosas no han rebasado límites en la cruzada anti inmigrantes del nuevo gobierno de Estados Unidos, o incluso saber de qué límites estamos hablando. En este caso, el presentador se refiere a una publicación que hizo la Casa Blanca a finales de marzo.

Audio de archivo, presentador: En plena tendencia de imágenes hechas con inteligencia artificial al estilo Ghibli, la cuenta oficial de la Casa Blanca subió una caricatura de una migrante llorando mientras era arrestada.

Silvia: Pero antes de eso, por ejemplo, en febrero, el gobierno de Trump publicó un video con sonidos e imágenes de migrantes esposados y encadenados, con un objetivo específico.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: En la cuenta oficial de X de la Casa Blanca fue compartido material audiovisual en el que se observan grilletes en manos y pies de migrantes que serían deportados en un vuelo, con la característica de mostrarlas en formato ASMR.

Silvia: Un formato de video que se conoce porque está pensado y editado para causar estímulos placenteros y relajantes en la audiencia.

Eliezer: Desde que volvió a la presidencia, hace menos de seis meses, Donald Trump ha dejado en claro que su promesa de combatir la migración va más allá de las políticas de mano dura. Su gobierno ha puesto en escena una crueldad deliberada contra los migrantes, y lo ha hecho en diferentes niveles. En marzo deportó a más de 200 venezolanos al CECOT, la cárcel para pandilleros de Bukele, en El Salvador, acusándolos de ser parte del grupo criminal Tren de Aragua, a pesar de que la mayoría no tenía antecedentes. Usó la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros para mandarlos a una prisión en otro país, sin que puedan pasar por la justicia. Y también ha intentado deportar a migrantes de otras nacionalidades a Sudán del Sur —entre ellos, tres latinoamericanos— y a Libia.

Silvia: A la vez, ha deportado a madres que tienen hijos que son ciudadanos y a chicos con cáncer; ha quitado protección a migrantes embarazadas y bebés en custodia; ha enviado a familias de Medio Oriente y Europa del Este que no podían regresar a sus países de origen —porque sus vidas corrían peligro por ser cristianos, por ejemplo, a distintos lugares de Centroamérica… Y, en medio de medidas de este tipo, ha mantenido una campaña de golpes de efecto para exhibir a los migrantes como delincuentes.

Audio de archivo, presentador: El gobierno de Donald Trump conmemoró sus primeros 100 días en el poder con una inusitada exhibición en los jardines de la Casa Blanca, mostrando fotografías de inmigrantes arrestados y acusados de delitos graves como asesinato, secuestro y agresión sexual infantil.

Silvia: Y esta semana, Trump firmó una proclamación que prohíbe o restringe la entrada de personas de 19 países, entre ellos Haití, Cuba y Venezuela. Dijo que lo que lo motivó fue un ataque en Colorado contra personas que pedían que Hamás libere a los rehenes israelíes… Porque según Trump el ataque muestra los “peligros extremos” de dejar entrar a personas a Estados Unidos sin investigar bien quiénes son.

Eliezer: El mensaje que este gobierno parece empeñado en transmitir es que los inmigrantes son todos una amenaza, sin distinción, y por lo tanto sus vidas no merecen consideración. Pero, para llegar a este punto, en una sociedad en la que viven cerca de 50 millones de inmigrantes, tienen que haber pasado muchas cosas. Donald Trump es, en todo caso, una nueva etapa de ese proceso, pero no es el comienzo.

Amparo Marroquín: En el caso de Trump, yo creo que es mucho más intencionado y mucho más pensado la manera como se construye al migrante, porque estoy construyendo al otro culpable de todos los males.

Silvia: Ella es Amparo Marroquín, profesora e investigadora de la Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas de El Salvador.

Amparo: Tengo que deshumanizarlo. Tengo que hacer que el estadounidense promedio se olvide de que el migrante le cuida a sus hijos. Tengo que hacer que el estadounidense promedio se olvide del migrante que lo llevó en el taxi y que fue súper simpático. Tengo que hacer que el estadounidense promedio se olvide de los festivales latinos donde bailas cumbia, salsa, bachata y merengue, y sos feliz. Y tienen que pensar que son otros (diferentes), otros, otros migrantes: animales salvajes, [criminales] tatuados, rapados, criminales.

Silvia: Amparo ha estudiado los procesos de migración entre Centroamérica y Estados Unidos durante 20 años, y gran parte de su trabajo se enfoca en el análisis del discurso. Es decir, en la forma en que las narrativas y el lenguaje reflejan y construyen realidades sociales. Como la que hoy afecta a millones de migrantes en suelo estadounidense, que se enfrentan a un fenómeno nuevo y antiguo a la vez.

Silvia: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: Y yo soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Hoy: de dónde vienen los principales imaginarios y estereotipos sobre los migrantes que dominan el discurso público en Estados Unidos, de qué tipo de realidades se nutren y cuándo empezaron a tomar las formas que conocemos actualmente.

Es 30 de mayo de 2025.

Silvia: Una pausa, y volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Silvia: Las políticas fronterizas y la migración han ocupado un lugar tan central en las campañas y las noticias de Estados Unidos en los últimos años que cuesta pensar que, hasta hace un par de décadas, tenían un lugar muy distinto en el debate público. En su trabajo académico, Amparo Marroquín señala que es posible rastrear este cambio en el discurso.

Eliezer: Tú dices que hubo una operación clave en el discurso de Estados Unidos en las últimas décadas, en la cual la migración pasó de ser una realidad económica que había que entender, a ser un problema que había que evitar. Ahora, lo que me saltó es… ¿hubo algún momento en los últimos… digamos, 50 años, en que la migración no haya sido vista como un problema, como una amenaza? Y… si fue así, ¿por qué cambió eso? ¿y cuándo?

Amparo: Mira, hasta donde nosotros lo hemos estudiado —digo “nosotros” porque hay muchos otros migrantólogos, digamos, en la región, trabajando este tema, pero en mi caso particular, que me he estado enfocando en los discursos, para mí el quiebre discursivo empieza con el presidente Bill Clinton; es decir, Bill Clinton va a ser el primer presidente que va a empezar a decir que hay demasiada gente llegando a los Estados Unidos.

Audio de archivo, Bill Clinton: Not only in the states heavily affected but in every place in this country are rightly disturbed by the large numbers of illegal aliens entering our country.

Amparo: Es decir, estamos hablando de finales del siglo pasado. Pero si nosotros nos ponemos en esta larga duración de hace 50 años ¿verdad?, de alguna manera, previo al presidente Clinton todavía había un discurso; vamos a decirlo así, ambiguo en relación con el tema migratorio, en donde, al menos me parece a mí, había como dos posturas de Estados Unidos que nos vamos a encontrar en este momento. Por un lado, una postura vinculada a: Estados Unidos es el melting pot (crisol de culturas), esta mezcolanza de culturas, y estamos abiertos a que venga gente porque sabemos que la inmigración ha sido la riqueza de los Estados Unidos. Es decir, los Estados Unidos se construyen como discurso nacional desde esta narrativa, que es una narrativa, me parece a mí, muy hermosa, muy interesante en este sentido, que quizá hacia el sur la podemos encontrar en Brasil, de pronto, pero no en muchos otros territorios. Entonces, ese elemento yo creo que es un elemento importante.

Y el otro elemento es: Estados Unidos, o buena parte de los Estados Unidos es particularmente sensible a los problemas políticos del continente o incluso extracontinentales. Y en este sentido, Estados Unidos, tierra de libertad, democracia y oportunidades, se va a abrir a proteger a aquellas personas que sean perseguidas en función de personajes que violentan los procesos democráticos, ¿no?.

Entonces, de hecho, cuando yo empiezo a revisar el discurso migratorio sobre El Salvador, es un discurso ambiguo, porque por un lado digamos, por ejemplo, en los años 80 Estados Unidos se debate entre si, en el caso de Centroamérica, particularmente El Salvador, que es donde más yo he estudiado si la migración centroamericana es una migración económica, porque somos pobres, o es una migración política, porque tenemos guerras; es decir, porque Nicaragua está incendiada, Guatemala está incendiada, El Salvador también. Entonces, si es una migración política, Estados Unidos tiene que abrir las puertas, porque Estados Unidos es esta tierra de la democracia y de la libertad, que tiene que abrirse a los perseguidos políticos. Donde ya es en el tema económico. Es decir, si estás migrando porque sos pobre, ahí sí no estamos muy claros de que te vamos a apoyar.

Silvia: En sus artículos, Amparo señala dos momentos claros de quiebre en el discurso oficial de Estados Unidos sobre la inmigración. El primero es el que acaba de mencionar, el que inaugura esta narrativa, con una operación que lanzó Bill Clinton en 1994, durante su primer gobierno.

Amparo: El presidente Clinton va a implementar las primeras políticas. Por ejemplo, esta Operación Gatekeeper, que es, “vamos a poner guardianes en la puerta”. Y es el primer momento en donde se habla de detener o de enviar militares a la frontera, por ejemplo, que a veces la gente lo suele identificar como un discurso más republicano, pero en realidad ha sido una constante a partir de, además, de un presidente demócrata que inaugura esta sensación inicial de preocupación.

Eliezer: ¿Puedes contar brevemente cómo fue esa operación o en qué consistió, y por qué es un hito para la forma en que vemos la migración ahora?

Amparo: Bueno, es una primera operación en donde lo que se hace es empezar a militarizar la frontera. Es decir, hay una diferencia muy grande entre las historias que te van a contar los migrantes que pasaban en los años setenta y ochenta del sur hacia Estados Unidos. En donde por supuesto que había policía migratoria que te podía buscar y esto, pero la gran mayoría de procesos migratorios eran exitosos. Luego, en la zona norte de México, toda esa gente que vivía en esa zona, en las zonas fronterizas, crecieron cruzándose, incluso a comprar al supermercado en Estados Unidos y regresando, ¿verdad? Es decir, había como… que suele ser muy, muy natural en muchas de las fronteras en distintos territorios en el mundo, ¿verdad? Es decir, la frontera siempre es un lugar de mucha movilidad. Lo que vamos a encontrar a partir de la Operación Gatekeeper es que esa movilidad se restringe completamente. Es decir, que ya no puedes ir y volver. Que, digamos, hay una operación, me parece a mí— también que racializa ese intercambio, ¿no? Es decir: tenemos a los ciudadanos de primera, que son ciudadanos estadounidenses, y tenemos luego a todo este montón de gente que está queriendo llegar y aprovecharse de este país maravilloso, ¿no?

Bill Clinton, audio de archivo: The jobs they hold may otherwise be by citizens or legal immigrants. The public services they use impose burdens on our taxpayers. That’s why our administration has moved aggressively to secure our borders more, by hiring a record number of new border guards, by deporting twice as many illegal aliens as ever before.

Amparo: Entonces, la Operación Gatekeeper no es tan exitosa en términos de detenciones, en términos de lo que consigue, pero me parece a mí que es un parteaguas en tanto que coloca… empieza a mover el tema de la migración hacia: “mmm, no es un derecho migrar, es un problema que tenemos que detener”, ¿no? Ese concepto de migración como derecho o migración como problema, para mí, se inaugura de manera oficial, o de manera política, a través de políticas de Estado con esa Operación Gatekeeper.

Audio de archivo, Bill Clinton: That’s why our administration has moved aggressively to secure our borders more by hiring a record number of new border guards, by deporting twice as many criminal aliens as ever before.

Eliezer: A mí me gustaría analizar varias cosas a partir de este momento, porque acá entran en escena algunos elementos que aparecen en tu investigación académica y que atraviesan las principales narrativas sobre migración hasta hoy, ¿no? Por un lado, con la Operación Gatekeeper, Estados Unidos desplaza también las rutas de cruce hacia las montañas y los desiertos, hacia zonas más inhóspitas, ¿no?, donde, claro, los migrantes deben tomar caminos más difíciles, solitarios, más peligrosos, y con eso aumentan las muertes y desapariciones, ¿no? Entonces, empiezan a utilizar un discurso disuasivo: “no intentes llegar a Estados Unidos, porque te expones a muchos peligros”, ¿no? Incluso la muerte. Pero los que causan estos peligros son ellos mismos.

Amparo: Claro, por supuesto. Es decir, a ver, siempre se dice: es que el migrante está escogiendo este tipo de caminos. Pero es que el migrante no escogía esos caminos. Es decir, otra vez ¿eh?, bueno, una de las cosas que yo he estudiado es cómo, por ejemplo, el coyotaje, como un oficio vinculado a los procesos migratorios, fue cambiando y evolucionando. Y los coyotes, en los años 80, en Centroamérica, se anunciaban en el periódico muchas veces. O había carteles en las calles que te decían: “Viaje a Estados Unidos”. Te decían: “Viaja a Estados Unidos sin visa” o algo así. Este, “No necesita visa”, “Este tanto”, ¿no? Entonces, había anuncios. O sea, sería súper interesante hacer solo una revisión de cómo te publicitaban, ¿no? Claro, pero eso tenía que ver justamente con que las rutas… Es decir, sabías la ruta, te ibas. Era como un viaje por tierra. Punto. Chao. ¿Verdad? Es decir, no había mucho más problema.

El asunto, como sucede con otro tipo de procesos, es que en la medida en que los colocas como un problema, como algo que no se debe hacer, los orillas a que se vuelvan cada vez más invisibles. Y los caminos invisibles, enfrentarte a una frontera que está militarizada implica buscar los puntos ciegos donde no hay vigilancia. Y por esos puntos ciegos ya no solamente pasan migrantes. En los puntos ciegos, el crimen organizado está moviendo todo tipo de ilícitos: armas, órganos. Y el crimen organizado, por definición, no puede tener testigos. Por tanto, digamos, la condición de migrar sin documentos se fragiliza, porque empezamos a cruzar el camino del migrante con el camino del crimen organizado. Porque son los únicos puntos ciegos que no están vigilados o que los Estados han decidido no vigilar, ¿verdad?

Silvia: Después de la pausa, cómo los grupos criminales de México descubren el negocio de secuestrar migrantes. Ya volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Silvia: En el segmento anterior, Amparo nos explicaba que el discurso sobre la migración en Estados Unidos empezó a cambiar a mediados de los 90, cuando se militariza la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México, y el gobierno empieza a utilizar un discurso disuasivo. Con la llegada del siglo XXI, ese proceso se acelera.

Amparo: Mira, yo creo que a lo largo de este siglo, ¿verdad? Llevamos justamente un cuarto de siglo, 25 años. Por alguna razón digamos, quizá porque necesito estudiarlo más, pero yo siento que cada década puedes encontrar como ciertos parteaguas que se vuelven muy complicados, ¿no? En 2001 tenemos el ataque sobre todo el más conocido, la parte de las Torres Gemelas, ¿verdad? El ataque a las Torres Gemelas, que lleva a remilitarizar las fronteras y, además, a colocar la migración como una amenaza a la seguridad nacional. Entonces, ese es un primer movimiento.

Silvia: Los ataques terroristas fueron hechos por personas que llegaron a Estados Unidos principalmente con visas de turista y de estudiante. Los procesos de inmigración y los controles fronterizos quedaron en la mira de inmediato. Y, además, dice Amparo, el país necesitaba chivos expiatorios.

Amparo: Se vuelve como muy evidente que ha sido gracias a la migración que ese tipo de violencia ha penetrado en los Estados Unidos. Y entonces, digamos, si tú llegabas a Estados Unidos sin documentos, tú estabas cometiendo un tipo de falta, que es una falta que va a ser juzgada a través de un juicio civil, que va a implicar multas, que va a implicar otro tipo de proceso que puede llegar a implicar la deportación, pero en casos muy extremos. Pero a partir de 2001, migrar sin documentos ya no es un problema legal que vas a poder resolver en un juicio civil. Ya se vuelve una amenaza a la seguridad nacional de Estados Unidos. Es decir, el discurso del siglo XXI se inaugura con el discurso, que luego va a ser copiado por muchos otros países receptores de: “La inmigración es una amenaza a la seguridad nacional”.

Eliezer: A partir de este momento de quiebre, que cimenta un nuevo discurso, Amparo identifica distintas situaciones que van a modelar las narrativas sobre los migrantes en este siglo, en particular sobre los centroamericanos.

Amparo Marroquín: La primera, diría yo, es quizá el huracán Stan, si no me equivoco.

Silvia: El huracán Stan azotó distintos países de Centroamérica y partes del sur de México a finales de 2005. Duró poco, pero causó miles de muertes y serios daños materiales. Entre ellos, uno que Amparo piensa que es clave para la forma en que se representa hoy la migración.

Amparo: El huracán destruye la primera estación de tren que había en Tapachula. Los migrantes atravesaban Centroamérica, pasabas Tecún Umán y caminabas 20 minutos, y estaba el tren ahí. Vos lo tomabas.

Eliezer: O sea, antes de 2005, una vez que pasaban la última ciudad de Guatemala y entraban a territorio mexicano, sólo tenían que hacer un tramo corto para llegar a la primera estación de la Bestia, el famoso tren de carga que atraviesa todo México hasta la frontera con Estados Unidos.

Amparo: Pero cuando se destruye esa estación del tren, tenés que caminar. Digamos que, en carretera, en carro, son dos horas de camino para llegar a la siguiente estación del tren, que está en Arriaga. Como el migrante no puede ser visto porque en 2001 ya nos dijeron que esto es grave y que no puedes hacerlo, entonces el migrante, en lugar de caminar por carretera, se adentra a la selva; y un trayecto que te toma dos horas en carro, a los migrantes les toma ocho días. Se adentra en un espacio que fue muy conocido como La Arrocera. En La Arrocera, Los Zetas: el crimen organizado, descubren que la gente está pasando por ahí. Y Los Zetas descubren que es muy barato y muy cómodo secuestrar a los migrantes, porque nadie sale a defender al migrante. Y que ahí sí: Los Zetas descubren un mercado impresionante para lucrarse, porque secuestran a los migrantes, llaman a la familia, piden la plata. Si la familia no da la plata, desaparecen al migrante. Lo matan. Se construye todo un escenario de terror que empieza en La Arrocera, que Óscar lo narró muy bien en su momento, y que se empieza a denunciar, pero que no se vuelve evidente hasta 2010, con la masacre de Tamaulipas.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: Comenzamos con un espeluznante hallazgo en Tamaulipas, México, a muy poca distancia de Brownsville, donde encontraron una fosa con 72 cadáveres.

Audio de archivo, corresponsal: Los cuerpos de 58 hombres y 14 mujeres de distintas nacionalidades fueron encontrados por la Marina de México. Al parecer, todos eran inmigrantes indocumentados.

Silvia: Lo que se conoce como la primera masacre de Tamaulipas o masacre de San Fernando, en agosto de 2010, fue una ejecución masiva atribuida al cártel de Los Zetas. Supuestamente, porque se habían negado a darles dinero o información de sus familiares en Estados Unidos, y después se negaron a trabajar para el cártel.

Amparo: Ahí se descubre que Los Zetas, desde Arriaga, bueno, desde Tapachula hasta Tamaulipas, es decir, atravesando todo el territorio mexicano, es el crimen organizado quien controla el movimiento y el flujo migratorio, y quién decide quién vive y quién muere, ¿no? Entonces, lo que nosotros vamos a tener sobre todo a partir de 2010, es que el problema del discurso que se construye en 2010 y que nosotros lo analizamos en periódicos en Ecuador, en Centroamérica y en México es que la narrativa es: estos migrantes fueron asesinados porque se negaron a colaborar con Los Zetas.

O sea, si vos vivís, si Amparo quedó viva, es porque colaboró con Los Zetas. Por tanto, cualquier migrante que llegue vivo a Estados Unidos seguramente transó con el crimen organizado, y seguramente, por tanto, ya no es de fiar. O sea, el único migrante bueno es el que está muerto en términos narrativos, es decir, no estoy diciendo que eso automáticamente… es decir, que los periodistas lo quisieron decir ni mucho menos, ¿verdad?

Pero cuando uno ve el conjunto de notas, hay como… como un… si uno lee el… o sea, lo que estás cubriendo, hay una insistencia en “te matan porque no colaboraste”. No se dice lo otro, pero de alguna manera se sobreentiende. Y, al mismo tiempo, tú vas a ver el aumento de esta narrativa de criminalización en Estados Unidos. Entonces funciona. Entonces, la siguiente década la inauguras construyendo una narrativa en donde el crimen organizado y la inmigración están muy imbricados.

Eliezer: Ahora, más allá de que vivimos en la época en que la desinformación es una industria muy lucrativa, en que se construyen relatos alternativos, se manipulan los hechos, la migración parece ser un asunto completamente impermeable a la evidencia. Sobre… o sea, la evidencia que hay sobre todo lo que dicen los números sobre el aporte de los migrantes a la economía, a la cultura, sobre su escasa participación en el delito, etcétera. ¿Por qué crees que es un asunto tan difícil de discutir públicamente de forma como más racional, más basada en la evidencia?

Amparo: ¿Estás pensando en Estados Unidos, no?

Eliezer: Exacto.

Amparo: Creo que porque… eh… Pero bueno, como he trabajado menos en Estados Unidos, pero desde Trump lo sigo muchísimo más, y creo que al menos en Centroamérica, no terminamos de entender la importancia de la disputa y de la lucha racial en Estados Unidos. Es decir, creo que no podemos entender el proceso migratorio solamente como una situación que se lee como una amenaza económica, cómo “me van a dejar sin empleo”. No. Hay un tema racial que yo creo que no terminamos de entender en el caso de Estados Unidos.

Silvia: El gobierno de Trump ha intentado, a su modo, dejarlo más claro, cuando hizo una excepción a su política de no dar asilo a inmigrantes:

Audio de archivo, presentadora: Decenas de sudafricanos blancos de ascendencia holandesa aterrizaron en Washington tras obtener el estatus de refugiados por una orden ejecutiva del presidente Trump. —Welcome, welcome to the United States of America.

Silvia: El argumento que utilizó Trump para justificar la entrega de beneficios a sudafricanos blancos es que son víctimas de violencia y persecución racial por parte de su gobierno. Estados Unidos acusa a Sudáfrica, sin ninguna evidencia, de que se está llevando a cabo un “genocidio blanco” en ese país. Es un relato que ha intentado imponer Elon Musk, que creció entre la élite blanca de Sudáfrica durante el régimen de segregación racial, el apartheid (el apartado).

Eliezer: También hay, por supuesto, elementos de clase, pero para Amparo eso no alcanza a eclipsar otro tipo de prejuicios.

Amparo: Es decir, en Europa, por ejemplo, hay una filósofa española, Adela Cortina, que insiste en que en España lo que existe es aporofobia. Es decir, es la fobia al migrante pobre. Es decir, no te molesta un migrante que tiene plata, sino un migrante pobre.

Silvia: Amparo cuenta que esta filósofa usa un término específico: aporofobia, que es el miedo o el rechazo a las personas pobres. Adela Cortina dice que, cuando se ataca a los migrantes en su país, es más por aporofobia que por xenofobia.

Amparo: Pero mi impresión en el caso de Estados Unidos es que, no importa si tenés plata, sos un marero, ¿ya? Entonces, aunque tengas plata… Entonces, hay un tema racial que no lo limpia la plata, vamos a decirlo así. Y me parece a mí que hay ahorita una operación extraña, en el caso de Donald Trump, en este momento en el que está hablando de la visa dorada, en donde está intentando quitar el tema racial y colocar, más bien, esa aporofobia. Es decir, el migrante que no merece respeto es el migrante pobre. Pero si vos tenés… si vos podés probar ¿cuántos son?, creo que son 20 millones, inmediatamente podés tener la visa dorada y tenés entrada libre todo el tiempo, lo que necesites y lo que querrás, ¿eh? Entonces… Pero, en el caso de Estados Unidos, ¿por qué no ha terminado de permear? Yo tampoco estaría tan clara de que no termina de permear. Es decir, yo creo que hay una parte importante de Estados Unidos que cada vez más se da cuenta de lo fundamental que es la migración. Pero lo que pasa es que los procesos culturales son procesos de larga duración. Son como dinosáuricos, ¿no?

Es decir, entonces, un dinosaurio, para que viva, o para que muera, o para que mueva la pata, tarda tiempo. Entre que el cerebro lo entiende y le da la orden al pie, pasa un tiempo. Entonces, lo mismo pasa, creo yo, con el proceso migratorio. Ha habido, me parece a mí, un avance muy interesante en defender los derechos de los migrantes. Ha habido un trabajo de organización de los mismos migrantes que es muy fuerte.

Eliezer: El problema es que, además de ser procesos lentos dice Amparo, la lucha por los derechos de los migrantes está atravesada por otras peleas.

Amparo: Los procesos culturales son así: avanzás dos pasos y retrocedés uno, y entonces así vas. Entonces, sí, con toda la lucha que ha habido, por ejemplo, por el movimiento negro en Estados Unidos todavía tenemos estos retrocesos. Mucho más la lucha por el tema migrante, que ha sido una lucha que inicia básicamente con el siglo. Es decir, antes no lo tenías. Pero historias, por ejemplo, como la de Solito, que se ha vuelto un best seller en Estados Unidos, creo que nos dicen justamente: sí, no estaría tan de acuerdo con vos. Ciertamente cuesta mucho que permee. Pero creo que va permeando. Pero estás luchando contra una matriz cultural racializada, profundamente racializada.

Silvia: Después de la pausa, las estrategias comunes de Trump y Bukele, y el uso político de la crueldad. Ya volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Silvia: Cuando entrevistamos a Amparo Marroquín, en marzo de este año, todavía no se conocían los detalles de la deportación de Kilmar Abrego García; tal vez el caso más representativo del valor que le da el gobierno de Trump a la vida de los migrantes. Abrego García fue enviado a la cárcel para pandilleros de El Salvador junto al grupo de más de 200 venezolanos que les contamos al principio, los que fueron acusados de formar parte del Tren de Aragua, aunque la mayoría no tenía antecedentes.

Eliezer: Este caso era peor todavía: Abrego García es salvadoreño, y contaba con una orden judicial que lo protegía de ser deportado a su país por temor a que pudiera sufrir represalias, incluso la muerte, por parte de una pandilla. La Casa Blanca llegó a reconocer que su expulsión había sido un error, pero dijo que ya no podía hacer nada. Después dijeron que igual era un criminal.

Audio de archivo, presentador: La Casa Blanca justificó su decisión de deportar y no traer de regreso a Kilmar Abrego García, el inmigrante enviado por error a El Salvador el 15 de marzo, a pesar de que la Corte Suprema le ordenó que facilitara su regreso. Esta tarde, la secretaria de prensa aseguró que Kilmar Abrego es pandillero y terrorista.

Silvia: En el momento en que hablamos con Amparo, Bukele todavía no se había convertido en el primer presidente de América Latina en ser invitado a una reunión oficial de trabajo con Donald Trump en la Casa Blanca, pero era evidente que estaban jugando el mismo juego, al menos a nivel discursivo.

Eliezer: Quisiera profundizar un poco sobre esto, porque justo cuando estaba leyendo tu trabajo y preparando la entrevista, de pronto tuve como un cruce entre clase y raza que, curiosamente, también me parece que de alguna manera une a Bukele y a Trump, digamos, ¿no? Claro, el presidente Nayib Bukele es un aliado de Donald Trump, pero bueno, también sigue esta, como, línea tradicional que han seguido todos los gobiernos salvadoreños, como tú dices, que básicamente es la sumisión al discurso de los Estados Unidos, ¿no? En este caso igual parece haber, como, algo más. Cuando empezó este gobierno de Trump, por ejemplo, recuerdo que cuentas oficiales como las de ICE o las de Homeland Security empezaron a publicar números de arrestos y deportaciones de la misma manera que Bukele hacía al comienzo del estado de excepción, ¿no?, con los arrestos. Y quería preguntarte si creés que se puede relacionar esa criminalización de los migrantes que hace Trump con la criminalización de la pobreza que ha implantado Bukele con el estado de excepción.

Amparo: Creo que se puede relacionar, pero creo que le funciona mejor al presidente Bukele que al presidente Trump. Y le funciona mejor al presidente Bukele porque este es un país más pequeño y somos más homogéneos. Pensamos más parecido. Pero un territorio tan grande como Estados Unidos, otra vez, es mucho más complejo y es más difícil. Y luego, porque ciertamente digamos, el presidente Bukele criminaliza la pobreza, pero le pone rostro de pandilla, rostro de mara. Y la mara y la pandilla, durante los últimos 25 años, se fueron construyendo como un enemigo público, no solo de El Salvador, sino de la región. Es decir, los adjetivos que vos encontrabas a la par de la pandilla son: asesinos, violadores… Es decir, son una mafia, son lo peor de lo peor.

En cambio, los adjetivos que encontrarás a la par de los migrantes son mucho más ambiguos. Entonces, creo que funciona menos bien. Porque además, digamos, vámonos a las vidas cotidianas. La vida cotidiana en Centroamérica: quien tuvo relación con la pandilla, siempre tiene una historia dolorosa, violenta. Es decir, el pandillero te extorsionaba, el pandillero te acosaba, te amenazaba con matarte o matar a tus hijos. En cambio, las historias cotidianas con la migración no necesariamente son esas. Es decir, ¿quién es el migrante? El migrante es el que te recoge los cultivos en toda la zona sur de Estados Unidos. El migrante es el que te limpia la mesa. El migrante… Es decir, sí, despreciémoslo porque es una raza inferior, pero me parece a mí que es un poco más difícil construirlo como el enemigo total. Entonces, creo que la posibilidad discursiva es un cacho más frágil, digamos. Es decir, si lo ponemos en escala del uno al diez, Bukele estaría en nueve y el presidente Trump estaría como en seis.

Es decir, por supuesto que ha sido un proceso exitoso, incluso porque muchos migrantes que votaron por Trump decían: “Claro, Trump persigue al migrante criminal, que no soy yo. Yo soy el buen migrante”, pero es más difícil, siento yo. Es decir, la tiene más dura. Ahora, tiene de paralelo a Elon Musk… o sea, eso: construirse, hacerse de un equipazo de comunicación, como el presidente Bukele también ha tenido un buen equipo de comunicación, que les permite dominar y manejar mucho más fácilmente las narrativas emocionales, ¿eh?

Eliezer: Eso es donde justamente me resulta complicado comprender, porque otra de las cosas que parece unir digamos no? a Bukele y a Trump, y sobre todo en su comunicación, es la crueldad explícita. La de tomar a gente como vehículo de la venganza que está llevando a cabo el presidente contra los enemigos del pueblo. Pero como tú acabas de decir, es más fácil de entender en el caso de El Salvador, ¿no?, donde la sociedad ha sido humillada y sometida a la violencia de las pandillas durante décadas. Pero cuesta ver de dónde nace ese resentimiento en Estados Unidos no? ¿Tú crees que todo este proceso de discurso sobre la migración, que se ha recrudecido, digamos, desde el primer gobierno de Trump, ha empujado la línea de lo tolerable, de lo que aceptamos como normal respecto de los migrantes?

Amparo: Yo creo que sí, definitivamente. Es decir, creo que lo que… o sea, la operación en el caso de Trump intenta digamos, bueno, mmm, quería buscar otra palabra, pero lo que busca es criminalizar al migrante. Es decir: el migrante no es cierto que sea este personaje trabajador que está llegando a Estados Unidos. En realidad, los que están llegando a Estados Unidos son asesinos. Y hay discursos de Trump donde lo dice, ¿no? O sea: “No está viniendo gente buena a Estados Unidos. Están viniendo homicidas, criminales…” Incluso digamos, en este discurso que hizo durante la campaña, donde dice: “A mí me cae bien el presidente Bukele, pero nos está mandando…” es decir “Limpia su país de asesinos y nos los está mandando a nosotros”, ¿no? Entonces, ahí hay como guiños muy, muy interesantes. Y digamos lo que yo pienso es, otra vez: si nosotros lo leemos desde el punto de vista racializado del discurso en Estados Unidos. ¿Por qué matar a una persona negra, por ejemplo? Pues por negro. O sea… Entonces, ¿por qué matar a un migrante? No es porque sea malo o porque… es decir, no necesitas llegar a eso. Osea hay como ciertas etiquetas que culturalmente se han venido colocando. Entonces, Trump lo que hace es acercar al migrante a ese imaginario donde los sujetos dejan de ser personas otra vez, ¿por eso, verdad? Y entonces puedes matarlos. No tienen alma, no tienen… o sea, no son… no son personas.

Silvia: Y si no son personas, como dice Amparo, se puede hacer cualquier cosa con ellos. Incluso usarlos para diversión del público, como en un circo romano. Algo que el gobierno de Estados Unidos ha evaluado realmente.

Audio de archivo, presentador: El gobierno de Trump está analizando hacer un reality de migrantes que compitan por la ciudadanía estadounidense. Divertirse con una especie de Juegos del Hambre de migrantes.

Silvia: Esta noticia fue difundida por distintos medios de Estados Unidos y confirmada por la portavoz del Departamento de Seguridad Nacional a mediados de mayo. Dijo que estaban evaluando una propuesta. Se dieron a conocer detalles.

Audio de archivo, presentador: Serían doce participantes, que llegarían en bote a la isla de Ellis, en Nueva York, al ladito de la Estatua de la Libertad, y viajarían alrededor de Estados Unidos en un tren llamado The American, que también sería el nombre del programa… En cada episodio, uno de los migrantes sería eliminado.

Silvia: Lo del reality show fue un escándalo con vida breve, como tantas otras cosas que el gobierno de Trump parece soltar para escandalizar, o para probar hasta dónde puede empujar los límites de lo tolerable. En cualquier caso, como decíamos al comienzo, para hacer un espectáculo de la crueldad contra los migrantes, para mostrar que no merecen dignidad.

Eliezer: Amparo Marroquín, muchas gracias.

Amparo: No, gracias a ustedes.

Silvia: Este episodio fue producido por Eliezer. Lo editamos Daniel Alarcón y yo. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido y la música son de Elías González. El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Suazo, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un pódcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación. Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Soy Silvia Viñas. Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

Eliezer Budasoff: Before we begin, we want to remind you that we’re currently running our fundraising campaign, and I’d like to ask for your support. We are a non-profit outlet, and our survival depends on listeners like you. Every story we produce is crafted with deep respect for the facts, the voices of our protagonists and experts, and for you, our audience.

Silvia Viñas: And in an increasingly polarized world, it’s harder to distinguish journalism from misinformation. Media outlets like ours matter now more than ever. But we can’t do this alone. If you haven’t donated yet, or if you’re able to help with an additional contribution, please consider doing so today. Join Deambulantes, our membership program. You can donate from just one dollar. Every bit helps. Go to elhilo.audio/donar and help us keep explaining Latin America. Thank you in advance!

Archival audio, testimony: Racism is on edge right now, and they do it just because you’re Hispanic. They don’t even check if you have documents.

Archival audio, host: The Tufts doctoral student was arrested while walking down the street near campus. Undercover agents ambushed her. Then five more people showed up, all wearing masks, and told her they were police officers.

Archival audio, report:

Host: How do you explain to a 5-year-old girl and her 11-year-old brother that their father was arrested by ICE right in front of them?

Boy: The officer grabbed him and pulled him out by force. And then… They handcuffed him, and hurt his hand.

Archival audio, host: It’s not the first time the U.S. has mocked migrants. But this time, it crossed the line…

Silvia: At this point, it’s hard to say what hasn’t already crossed the line in the anti-immigrant crusade of the new U.S. government or even what “line” we’re talking about. In this case, the host is referring to a post the White House made at the end of March.

Archival audio, host: In the middle of the Ghibli-style AI image trend, the official White House account posted a cartoon of a migrant woman crying while being arrested.

Silvia: But before that, for example, in February, the Trump administration released a video with sounds and images of migrants handcuffed and shackled, with a specific purpose.

Archival audio, host: On the official White House X account, they shared audiovisual content showing migrants with shackles on their hands and feet being deported on a flight edited in ASMR format.

Silvia: A video format known for being designed and edited to elicit pleasant and relaxing sensations in its audience.

Eliezer: Since returning to the presidency less than six months ago, Donald Trump has made it clear that his promise to combat migration goes far beyond tough-on-immigration policies. His administration has staged a deliberate cruelty toward migrants, and done so on multiple levels. In March, he deported over 200 Venezuelans to CECOT, Bukele’s prison for gang members in El Salvador, accusing them of belonging to the criminal group Tren de Aragua, even though most had no criminal record. He used the Alien Enemies Act to send them to prison in another country, without giving them access to a court of law. He has also attempted to deport migrants of other nationalities to South Sudan including three Latin Americans and to Libya.

Silvia: At the same time, he has deported mothers with U.S. citizen children, and kids with cancer; he’s removed protections from pregnant migrants and babies in custody; he has sent families from the Middle East and Eastern Europe who couldn’t return to their home countries because their lives were in danger for being Christian, for example to various parts of Central America. And amid these kinds of measures, he’s continued a shock campaign to portray migrants as criminals.

Archival audio, host: Donald Trump’s government marked its first 100 days in office with a striking exhibition in the White House gardens, displaying photographs of immigrants arrested and charged with serious crimes like murder, kidnapping, and child sexual assault.

Silvia: And this week, Trump signed a proclamation that prohibits or restricts the entry of people from 19 countries, including Haiti, Cuba and Venezuela. He said that what motivated him was an attack in Colorado against people who asked Hamas to release the Israeli hostages… Because according to Trump the attack shows the “extreme dangers” of letting people into the United States without investigating well who they are.

Eliezer: The message this administration seems determined to send is that all immigrants are a threat, without distinction, and therefore their lives aren’t worthy of consideration. But to reach this point in a society where nearly 50 million immigrants live, many things had to happen. Donald Trump is, in any case, a new phase of that process, but he’s not the beginning.

Amparo Marroquín: In Trump’s case, I think the way the migrant is constructed is much more intentional and calculated, because you’re building “the other” as the one to blame for everything.

Silvia: This is Amparo Marroquín, professor and researcher at the Central American University José Simeón Cañas in El Salvador.

Amparo: I have to dehumanize him. I have to make the average American forget that the migrant takes care of their children. I have to make the average American forget about the migrant who drove them in the taxi and was super nice. I have to make the average American forget about the Latino festivals where you dance cumbia, salsa, bachata, and merengue, and you’re happy. And they have to think of them as other people, different ones, other, other migrants: wild animals, tattooed [criminals], shaved heads, criminals.

Silvia: Amparo has studied migration processes between Central America and the United States for 20 years, and much of her work focuses on discourse analysis. That is, on how narratives and language reflect and construct social realities like the one that currently affects millions of migrants living on U.S. soil, who are facing a phenomenon that is both new and old at the same time.

Silvia: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: And I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Today: Where do the dominant imaginaries and stereotypes about migrants in the U.S. public discourse come from? What kinds of realities do they draw from? And when did they begin to take on the forms we now recognize?

It’s June 6th, 2025.

Silvia: A quick break, and we’ll be back.

Eliezer: We’re back on El hilo.

Silvia: Border policy and migration have taken such a central place in U.S. campaigns and news coverage in recent years that it’s hard to imagine that, just a couple of decades ago, they held a very different place in public debate. In her academic work, Amparo Marroquín points out that this shift in discourse can be traced.

Eliezer: You say there was a key shift in U.S. discourse in recent decades, where migration went from being seen as an economic reality that needed to be understood, to being treated as a problem that had to be stopped. What struck me was… has there been a time in the past… say, 50 years, when migration wasn’t seen as a problem, as a threat? And… if so, why did that change? And when?

Amparo: Look, as far as we’ve studied it and I say “we” because there are many other migration scholars in the region working on this topic, but in my particular case, since I’ve focused on discourse, for me the discursive break begins with President Bill Clinton. That is, Clinton will be the first president to start saying there are too many people coming into the United States.

Archival audio, Bill Clinton: Not only in the states heavily affected but in every place in this country are rightly disturbed by the large numbers of illegal aliens entering our country.

Amparo: So we’re talking about the end of the last century. But if we go back across this longer span of the last 50 years, there was still, let’s say, an ambiguous discourse around migration, at least that’s how I see it. There were, I think, two coexisting postures in the United States that we still see today. On one hand, a narrative linked to the idea of the U.S. as a melting pot, this mixture of cultures, and the belief that immigration has been the country’s greatest wealth. That is, the United States builds its national narrative from this idea, one I find very beautiful and interesting. You might find something similar further south, maybe in Brazil, but not in many other places.

So that element, I think, is important.

Amparo: And the other element is this: the United States, or at least a significant part of it, is particularly sensitive to political problems in the region, or even beyond the continent. In that sense, the U.S., as the land of freedom, democracy, and opportunity, will open its doors to protect those being persecuted by actors who threaten democratic processes, right?

In fact, when I started reviewing the migration discourse around El Salvador, it was an ambiguous one. Because on the one hand, for example, in the 1980s the U.S. debated whether Central American migration, especially from El Salvador (which is what I’ve studied most), was economic migration because we were poor, or political migration, because we had wars. I mean, Nicaragua was in flames, Guatemala was in flames, and El Salvador too. So if it’s political migration, the U.S. has to open its doors, because it’s this land of democracy and freedom that should welcome political refugees. But when it comes to economic reasons, if you’re migrating because you’re poor then things are less clear about whether support will come.

Silvia: In her writings, Amparo points to two clear turning points in the official U.S. discourse on immigration. The first is the one she just mentioned, the beginning of this new narrative, launched through an initiative from Bill Clinton in 1994, during his first term.

Amparo: President Clinton will implement the first set of policies. For example, Operation Gatekeeper, which literally means: “we’re going to place gatekeepers at the door.” It’s the first time we hear about stopping migration or sending troops to the border, something people often associate with Republican rhetoric, but in reality, it starts with a Democratic president and this initial sense of alarm.

Eliezer: Can you briefly explain what that operation was about, what it consisted of, and why it’s a landmark in the way we see migration today?

Amparo: Well, it was the first operation where the goal was to start militarizing the border. That is, there’s a huge difference between the stories migrants tell from the ’70s and ’80s about crossing from the south into the United States. Of course there were immigration police who could catch you and all that, but most migration processes were successful. And then, in northern Mexico, the people who lived in that region, along the border zones, grew up crossing back and forth, sometimes just to go shopping in U.S. supermarkets and then returning, right? This was and still is, in many parts of the world, a very natural dynamic for border regions. Borders are usually places of a lot of movement.

What we start to see after Operation Gatekeeper is that this mobility is completely restricted. You can’t just come and go anymore. And what happens, in my view, is also a racialization of that exchange. In other words: we now have first-class citizens (U.S. citizens) and then all these people trying to get in and take advantage of this wonderful country.

Archival audio, Bill Clinton: The jobs they hold may otherwise be by citizens or legal immigrants. The public services they use impose burdens on our taxpayers. That’s why our administration has moved aggressively to secure our borders more, by hiring a record number of new border guards, by deporting twice as many illegal aliens as ever before.

Amparo: So, Operation Gatekeeper isn’t that successful in terms of arrests or results but in my opinion, it marks a turning point because it begins to shift how migration is framed: from “migration is a right” to “migration is a problem we need to stop,” right? That shift, from migration as a right to migration as a problem is, for me, officially and politically inaugurated through state policy with Operation Gatekeeper.

Archival audio, Bill Clinton: That’s why our administration has moved aggressively to secure our borders more, by hiring a record number of new border guards, by deporting twice as many criminal aliens as ever before.

Eliezer: There are a few things I’d like to unpack from this moment, because some key elements you touch on in your academic research appear here and still shape the dominant narratives around migration today, right? For one, with Operation Gatekeeper, the U.S. also pushes crossing routes into the mountains and deserts much more inhospitable zones, where migrants have to take longer, riskier, and lonelier paths. And that, in turn, increases deaths and disappearances, right?

So the message becomes a deterrent: “Don’t try to come to the U.S. you’re risking your life.” Even death. But the thing is… those dangers are created by the very people trying to deter them.

Amparo: Exactly. Of course. People always say: migrants choose these kinds of routes. But that’s not true, migrants didn’t choose those routes. One of the things I’ve studied is how coyotaje (human smuggling) the business of smuggling people across borders has evolved. In the 1980s in Central America, coyotes would often advertise in newspapers. You’d see flyers on the streets that said: “Trips to the United States.” They’d say: “Travel to the U.S. without a visa.” Or “No visa needed.” Or give a price, right? It would actually be fascinating to review how these trips were marketed. Because the route was simple: you knew it, you took it. It was like a road trip. That’s it. No big deal.

But, like with many other things, once you frame it as a problem as something that shouldn’t be done; you start forcing it underground. And when you face a militarized border, you have to look for blind spots, areas without surveillance. And through those blind spots, it’s no longer just migrants who are crossing. In those blind spots, organized crime moves all kinds of illicit goods: weapons, organs. And organized crime, by definition, can’t have witnesses. So undocumented migration becomes extremely vulnerable, because now the path of the migrant intersects with the path of criminal organizations. Because those are the only routes left unwatched, or that the state chooses not to watch.

Silvia: After the break, how Mexico’s criminal groups discovered the business of kidnapping migrants. We’ll be right back.

Eliezer: We’re back on El hilo.

Silvia: In the last segment, Amparo explained how the U.S. discourse on migration began to shift in the mid-1990s, when the U.S.-Mexico border was militarized and the government started using deterrent messaging. With the arrival of the 21st century, that process accelerated.

Amparo: Look, I think throughout this century, we’re just now 25 years in for some reason, and maybe I need to study this more, but it seems like every decade has certain flashpoints that become really complicated, right? In 2001 we had the attack above all, the most well-known one, the Twin Towers, right? The attack on the Twin Towers led to re-militarizing the borders and, at the same time, to framing migration as a threat to national security. So that’s the first major shift.

Silvia: The terrorist attacks were carried out by people who mostly entered the U.S. with tourist or student visas. Immigration processes and border control immediately came under scrutiny. And, as Amparo says, the country needed scapegoats.

Amparo: It became very obvious that migration was the reason this kind of violence had penetrated the U.S. And so, if you entered the U.S. without documents, you were committing a violation, but it was a civil violation. It meant fines or other processes that could lead to deportation, but usually only in extreme cases. After 2001, though, undocumented migration was no longer a civil legal issue; it became a threat to national security. In other words, 21st-century discourse begins with this idea, which many other migrant-receiving countries later copied as “immigration is a threat to national security.”

Eliezer: From that turning point, which cemented a new discourse, Amparo identifies various events that have shaped how migrants are portrayed in this century, particularly Central American migrants.

Amparo Marroquín: The first one, I’d say, is probably Hurricane Stan, if I’m not mistaken.

Silvia: Hurricane Stan hit several Central American countries and parts of southern Mexico in late 2005. It was short-lived but caused thousands of deaths and serious material damage, including one consequence that Amparo believes is key to how migration is represented today.

Amparo: The hurricane destroyed the first train station in Tapachula. Migrants would cross through Central America, pass through Tecún Umán, and just walk 20 minutes to reach the train. You’d hop on right there.

Eliezer: So, before 2005, once migrants crossed the last Guatemalan city and entered Mexican territory, they only had a short walk to the first station of La Bestia, the infamous freight train that travels all the way through Mexico to the U.S. border.

Amparo: But when that train station was destroyed, you had to walk. By road, by car, it’s a two-hour trip to the next station in Arriaga. But because migrants can’t be seen since in 2001 we were told that this is serious and you can’t do it, then instead of walking along the road, migrants head into the jungle. And a journey that would take two hours by car ends up taking them eight days on foot.

They enter a place that became widely known as La Arrocera. And there, Los Zetas, the criminal group, realized that people were passing through. And Los Zetas discovered it was cheap and easy to kidnap migrants. Because no one defends them. And there, Los Zetas found an incredibly profitable market. They’d kidnap migrants, call their families, demand money. If the family couldn’t pay, they’d make the migrant disappear. They’d kill them.

A whole scene of terror began in La Arrocera, which Óscar documented really well at the time and which people started denouncing, but which didn’t become widely visible until 2010, with the Tamaulipas massacre.

Archival audio, host: We begin with a horrifying discovery in Tamaulipas, Mexico, not far from Brownsville, where a mass grave was found containing 72 bodies.

Archival audio, correspondent: The bodies of 58 men and 14 women of various nationalities were found by the Mexican Navy. Apparently, all of them were undocumented immigrants.

Silvia: What became known as the first Tamaulipas massacre, or the San Fernando massacre, in August 2010, was a mass execution attributed to the Zetas cartel. Allegedly, the victims had refused to hand over money or give information about their relatives in the United States, and later refused to work for the cartel.

Amparo: That’s when it became clear that Los Zetas, from Arriaga, or really from Tapachula all the way to Tamaulipas, meaning across the entire Mexican territory, were the ones controlling the migrant movement. Organized crime was deciding who lived and who died, right? So, what we see from 2010 onward is that the problem with the narrative being constructed and we analyzed this in newspapers from Ecuador, Central America, and Mexico is that the story becomes: these migrants were killed because they refused to collaborate with Los Zetas.

In other words, if someone like Amparo survived, it’s because she cooperated with the Zetas. So, any migrant who arrives alive to the U.S. probably made a deal with organized crime and therefore, can’t be trusted.

The only “good” migrant, narratively speaking, is the dead one. I’m not saying journalists meant to say that but if you look at the overall coverage, there’s a kind of… If you read what’s being published, there’s a repeated message: “they were killed because they didn’t cooperate.” The other possibility is never mentioned, but it’s implied. And at the same time, you see this rising narrative of criminalization in the U.S. So it works.

That following decade begins with a narrative in which organized crime and immigration are deeply entangled.

Eliezer: Now, beyond the fact that we live in an era where disinformation is a highly lucrative industry, where alternative narratives are manufactured and facts are manipulated, migration seems to be an issue that’s completely impermeable to evidence. I mean… There’s a ton of data showing how migrants contribute to the economy, to culture, how low their crime rates actually are, etc. Why do you think it’s so hard to have a more rational, evidence-based public discussion about this?

Amparo: You’re talking about the United States, right?

Eliezer: Exactly.

Amparo: I think it’s because… well, even though I’ve worked less directly in the U.S., I’ve followed things much more closely since Trump. And I think, at least in Central America, we still don’t fully understand the depth of the racial tensions and struggles in the U.S. That is, we can’t understand the migration process solely as an economic threat, like, “they’re going to take our jobs.” No. There’s a racial component that we just don’t fully grasp when it comes to the U.S.

Silvia: The Trump administration, in its own way, made that clearer especially when it made an exception to its policy of denying asylum to immigrants:

Archival audio, host: Dozens of white South Africans of Dutch descent landed in Washington after receiving refugee status through an executive order from President Trump. Welcome, welcome to the United States of America.

Silvia: Trump’s justification for granting those white South Africans refugee benefits was that they were victims of violence and racial persecution by their government. The U.S. accused South Africa, without any evidence of carrying out a “white genocide.” It’s a narrative Elon Musk has tried to promote, having grown up among South Africa’s white elite during the apartheid regime.

Eliezer: Of course, there are also class dynamics at play, but for Amparo, that doesn’t override other types of prejudice.

Amparo: I mean, in Europe, for example, there’s a Spanish philosopher, Adela Cortina, who insists that what exists in Spain is aporophobia. That is, fear or rejection of the poor migrant. So it’s not that a wealthy migrant bothers you it’s the poor migrant.

Silvia: Amparo explains that this philosopher uses a specific term: aporophobia, which refers to the fear or rejection of poor people. According to Adela Cortina, when migrants are attacked in her country, it’s more out of aporophobia than xenophobia.

Amparo: But in the case of the United States, my impression is that it doesn’t matter if you have money, you’re still seen as a marero (gang member), right? Even if you have money… So there’s a racial issue that money can’t wash away, let’s put it that way. And I think right now, with Donald Trump, we’re seeing a strange operation. He’s talking about the golden visa, trying to shift the discourse from being about race to one of aporophobia. That is, the migrant who doesn’t deserve respect is the poor one. But if you can prove what it is, twenty million dollars? You immediately qualify for the golden visa and have free entry whenever you want, for whatever you want.

So… in the case of the U.S., has the reality of migration failed to take root in public understanding? I’m not entirely sure it hasn’t. I think there’s a significant portion of the U.S. population that is increasingly aware of how essential migration is. But cultural processes take a long time. They’re dinosauric.

Like, for a dinosaur to live, or die, or move its leg, it takes time. Between the brain realizing it and sending the message to the foot, time passes. I think it’s the same with the migration process. I believe there’s been very interesting progress in defending migrants’ rights. There’s been strong organizing work from migrants themselves.

Eliezer: The problem, Amparo says, is that in addition to being slow-moving, the fight for migrant rights is entangled with other struggles.

Amparo: Cultural processes are like that: you move two steps forward and one step back and that’s how it goes. So yes, even with all the efforts, for example, around the Black civil rights movement in the U.S., we still see setbacks. And even more so with the migrant movement, which is a much newer struggle, one that basically began with this century. Before that, it didn’t really exist. But stories like Solito, for example, which has become a bestseller in the U.S. I think those show us exactly that: I wouldn’t completely agree with you. Yes, it’s hard for this to take root. But I do think it’s starting to. Still, you’re up against a deeply racialized cultural matrix.

Silvia: After the break: the common strategies of Trump and Bukele, and the political use of cruelty. We’ll be right back.

Eliezer: We’re back on El hilo.

Silvia: When we interviewed Amparo Marroquín in March of this year, the details about the deportation of Kilmar Abrego García were not yet known. It may be the most representative case of how little the Trump administration values migrant lives. Abrego García was sent to the gang prison in El Salvador alongside the group of over 200 Venezuelans we mentioned earlier, the ones accused of being part of Tren de Aragua, even though most had no criminal record.

Eliezer: This case was even worse: Abrego García is Salvadoran, and he had a court order protecting him from being deported to his country because of fear that he could face retaliation or even death at the hands of a gang. The White House admitted his expulsion had been a mistake, but said there was nothing they could do anymore. Later, they claimed he was a criminal anyway.

Archival audio, host: The White House justified its decision to deport, and not bring back Kilmar Abrego García, the immigrant mistakenly sent to El Salvador on March 15, despite a Supreme Court order to facilitate his return. This afternoon, the press secretary claimed that Kilmar Abrego is a gang member and a terrorist.

Silvia: At the time we spoke with Amparo, Bukele had not yet become the first Latin American president to be officially invited to a working meeting with Donald Trump at the White House, but it was already clear they were playing the same game, at least at the level of discourse.

Eliezer: I’d like to dig a bit deeper into that, because while I was reading your work and preparing for the interview, I suddenly saw this intersection of class and race that, curiously, also seems to connect Bukele and Trump, right? Sure, President Nayib Bukele is an ally of Donald Trump, but he also follows this traditional line taken by all Salvadoran governments, as you’ve said, which is essentially submission to the U.S. discourse, right?

But in this case, it also seems like something more. When this Trump administration began, for example, I remember that official accounts like ICE’s or Homeland Security’s started posting arrest and deportation numbers in the same way Bukele did at the beginning of his state of exception, with arrest counts. And I wanted to ask you whether you think there’s a link between Trump’s criminalization of migrants and Bukele’s criminalization of poverty through the state of exception.

Amparo: I think the connection can be made but I think it works better for President Bukele than for President Trump. And it works better for Bukele because this is a smaller, more homogenous country. We think more alike. But a country as vast as the United States is much more complex and harder to manage.

And then there’s this: Bukele does criminalize poverty, but he gives it the face of the gang, of the mara. And over the last 25 years, the gang has been constructed as a public enemy, not just in El Salvador, but across the region. The adjectives you find next to the word “gang” are things like: murderers, rapists… a mafia, the worst of the worst.

Whereas the adjectives linked to “migrants” are much more ambiguous. So I think it’s less effective. Because also let’s talk about everyday life. In Central America, if you’ve had any contact with a gang, it’s always a painful, violent story. The gang member extorted you, harassed you, threatened to kill you or your children. But everyday stories about migration aren’t necessarily like that. Who is the migrant?

The migrant is the one who harvests your crops in the American South. The migrant is the one who clears your table. The migrant… So yes, let’s look down on them because they belong to an “inferior race,” but I think it’s a bit harder to construct them as the total enemy. So I think the discursive possibility is slightly weaker. On a scale from one to ten, I’d say Bukele is at a nine and President Trump is around a six.

Amparo: I mean, of course it’s been a successful process, even because many migrants who voted for Trump would say: “Sure, Trump is going after the criminal migrant. That’s not me. I’m the good migrant.” But still, I think it’s harder for him. Now, he does have Elon Musk in his corner… I mean, that: building a powerful communications team just like President Bukele has had an excellent media team which lets them dominate and shape emotional narratives much more effectively.

Eliezer: That’s exactly the part I struggle to understand, because another thing that seems to link Bukele and Trump especially in their messaging, is explicit cruelty. The idea of using people as vehicles for the president’s revenge against so-called enemies of the people. But like you just said, it’s easier to understand in El Salvador, where society has been humiliated and subjected to gang violence for decades.

But in the U.S. where does that resentment come from? Do you think this entire process of increasingly harsh anti-immigrant discourse, especially since Trump’s first presidency, has pushed the boundaries of what’s acceptable, of what we consider “normal” when it comes to how migrants are treated?

Amparo: I absolutely think so. That is I think what… well, I was looking for another word, but what Trump’s operation seeks to do is criminalize the migrant. The migrant isn’t this hardworking person coming to the U.S. no. According to Trump, those arriving are murderers.

And he’s said that in speeches, right? Like: “Good people aren’t coming to the United States. Murderers, criminals are coming…” Even in a campaign speech, he said something like: “I like President Bukele, but he’s sending us his criminals.” As in, “He’s cleaning up his country by sending us his murderers,” right? There are very revealing moments like that.

And here’s what I think: if we look at it from the racialized perspective of U.S. discourse… Why do you kill a Black person, for example? Just for being Black. So why do you kill a migrant? It’s not because they’re bad or because… you don’t even need to go there. There are these labels that, culturally, have been attached. So what Trump does is bring the migrant closer to that imaginary, where individuals are no longer people. That’s why. And then you can kill them. They have no soul, no… they aren’t people.

Silvia: And if they’re not people, like Amparo says, then anything can be done to them. Even using them for the public’s amusement like in a Roman circus. Something the U.S. government has seriously considered.

Archival audio, host: The Trump administration is considering creating a reality show where migrants compete for U.S. citizenship. Entertainment in the form of a kind of Hunger Games for migrants.

Silvia: This story was reported by various U.S. media outlets and confirmed by the spokesperson for the Department of Homeland Security in mid-May. Details were released.

Archival audio, host: There would be twelve participants, arriving by boat to Ellis Island, in New York, right next to the Statue of Liberty. They would travel around the U.S. on a train called The American, which would also be the name of the show… In each episode, one migrant would be eliminated.

Silvia: The reality show idea caused a brief scandal, like so many things the Trump administration seems to float either to shock or to test how far they can push the limits of what’s tolerable. In any case, as we said at the beginning: it’s about turning cruelty against migrants into a spectacle, to show that they don’t deserve dignity.

Eliezer: Amparo Marroquín, thank you so much.

Amparo: No, thank you.

Silvia: This episode was produced by Eliezer. It was edited by Daniel Alarcón and me. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design and music by Elías González. The rest of El hilo’s team includes Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Suazo, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent, rigorous journalism, we ask that you join our membership program. Latin America is a complex region, and our journalism depends on listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to dive deeper into today’s episode, subscribe to our newsletter at elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it out every Friday.

You can also follow us on social media. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook, and Threads. You’ll find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments and tag us when you share episodes.

I’m Silvia Viñas. Thanks for listening.