Suicidio

Tasa de suicidio Latinoamérica

Uruguay

Salud mental

Este episodio toca temas sensibles de salud mental que pueden ser detonantes, incluyendo el suicidio. Puede no ser apto para todos los oyentes. Por favor, ten en cuenta este mensaje a la hora de escuchar. Aquí puedes encontrar información sobre cómo acceder a líneas telefónicas de atención psicológica desde diferentes países de la región.

Uruguay tiene una de las tasas más altas de suicidio en el continente: 21 cada 100.000 habitantes. En las Américas, la tasa es de 9. ¿Por qué un país que suele verse como modelo de bienestar y estabilidad en la región tiene una tasa de suicidios más alta que el promedio? Para tratar de entender qué hay detrás de esa cifra y cómo se enfrenta una crisis así, conversamos primero con Glenda Ghan, madre de una adolescente que se quitó la vida en 2022, que nos cuenta las dificultades que enfrentó para atender los problemas de salud mental de su hija y por qué hace falta romper el tabú social y poner este tema en la conversación pública. Luego, la psiquiatra Sandra Romano, vicepresidenta de la Sociedad de Psiquiatría de Uruguay, nos ayuda a explorar algunas causas vinculadas con este fenómeno y qué podemos hacer para ayudar.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Nausícaa Palomeque -

Edición

Silvia Viñas, Eliezer Budasoff, Daniel Alarcón -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción en redes sociales

Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Elías González, Remy Lozano -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

Fotografía

Nausícaa Palomeque

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Elías González: Este episodio toca temas sensibles de salud mental, incluyendo el suicidio, que pueden ser detonantes y puede no ser apto para todos los oyentes. Por favor, considera este mensaje y escucha a discreción propia. Gracias.

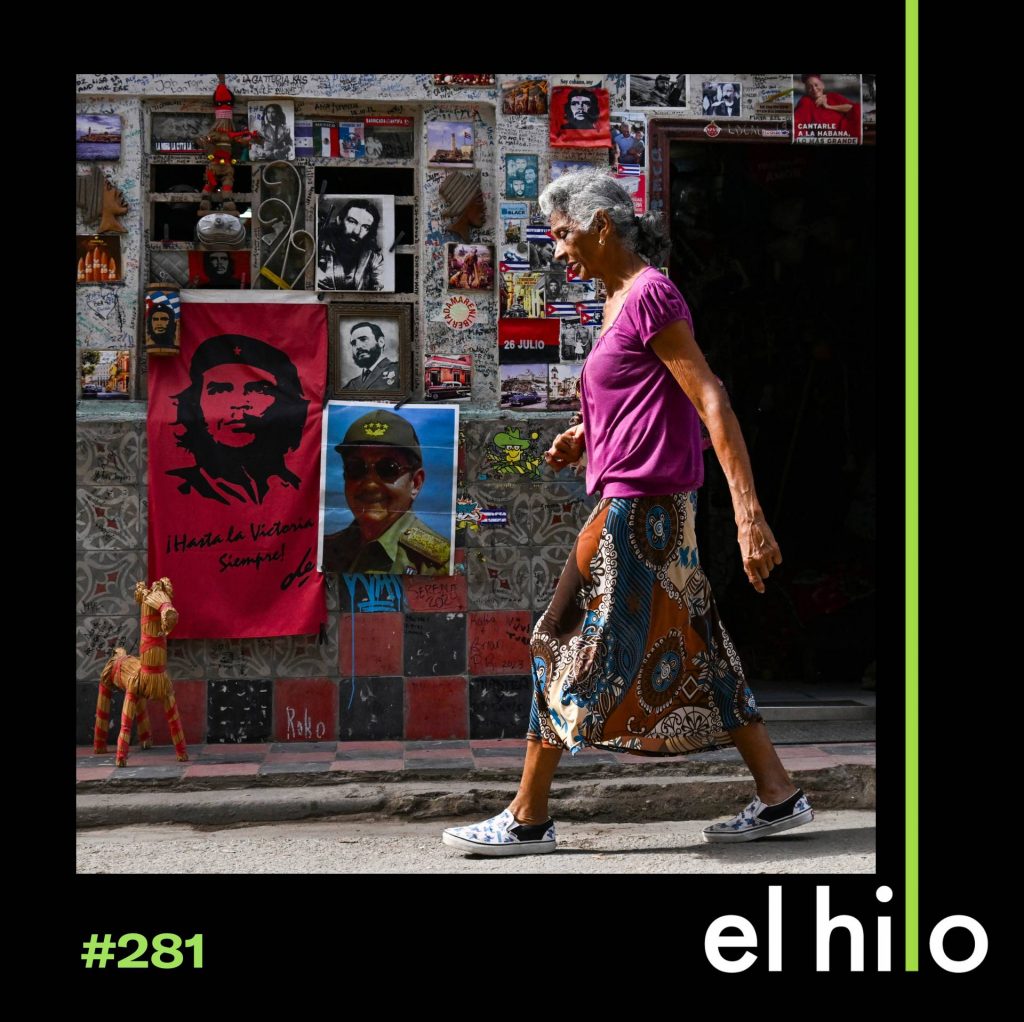

Silvia Viñas: Es una tarde gris de mayo de 2024 en Montevideo, y en la plaza Independencia, una plaza emblemática de la capital uruguaya, hay unos cubos con fotos de personas que se suicidaron. Son 11 cubos grandes, de 2 metros por dos metros, con 11 retratos: Joaquín, vestido con un traje de karateka, 23 años. Matías abrazando a un perro, 33 años. Javier en la playa, 42. Lucas sonriendo, 16. Olga, también sonriendo, 66 años.

Glenda Ghan: No lo sabemos ¿por qué? Solo sabemos que sentían dolor y no podían más con esta vida. El por qué, cada uno de ellos sabrá por qué.

Eliezer Budasoff: Ella es Glenda Ghan, tiene 43 años, y dos hijas. Una de las fotos en la plaza es de una de ellas: Melissa. Se suicidó en junio del 2022. Tenía 19 años.

En la foto se ve a una muchacha con los ojos grandes y oscuros, que mira, seria, a la cámara.

Glenda: Esa foto es como que es raro hasta caminar adelante de ella, porque todo el tiempo parece que te está mirando. Y esa era su mirada. Esos ojos grandotes. De dónde estés parece como que te está mirando.

Eliezer: Esta instalación en la Plaza Independencia es parte de una campaña que se llama “La última foto”. Participaron familiares de uruguayos que se suicidaron, organizaciones sociales, sociólogos, psicólogos, psiquiatras. Es un proyecto que replica una experiencia que se hizo en Reino Unido para prevenir el suicidio y promover la salud mental. El objetivo central de la campaña en Uruguay es hablar de suicidio.

Silvia: Para la exposición contactaron a sobrevivientes, como suelen llamar a los familiares y amigos de personas que se suicidaron. Los invitaron a participar y a los que aceptaron, les pidieron fotos recientes de sus seres queridos. Glenda eligió varias fotos de su hija: en salidas familiares, con su hermana Agustina, posando como modelo, jugando con sus perros.

Glenda: La foto que eligieron ellos fue una de varias sesiones que ella se hizo con mi hermano que le sacó la foto, que es esta. Como que tiene una mirada de modelo, que no era modelo ni nada, pero como toda gurisa le gustaba sacarse fotos y a veces hacían eso, un fin de semana se tiraban hasta ahí y se sacaban fotos con algún fondo y bueno, eligieron esta.

Silvia: Glenda se ha preguntado qué diría su hija de este proyecto. Si estaría de acuerdo con compartir su historia.

Glenda: Y yo creo que sí, que ella piensa que esto está bien, que esto está bien, que nadie más tiene que pasar por el dolor y lo que a ella la llevó a quitarse la vida. Eso es lo que me dice la foto.

Eliezer: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: Y yo soy Silvia Viñas.

Uruguay tiene una de las tasas más altas de suicidio en el continente: 21 cada 100.000 habitantes. En Las Américas, la tasa es de 9.

Hoy, por qué un país que suele verse como modelo de bienestar y estabilidad en la región tiene una tasa de suicidios más alta que el promedio. Qué hay detrás de esta cifra y cómo se enfrenta una crisis así.

Es 4 de abril de 2025.

Eliezer: Nuestra productora, Nausícaa Palomeque, quería entender por qué su país tiene una tasa tan alta de suicidio y reporteó este tema desde Montevideo. Nausícaa nos sigue contando.

Nausícaa: En junio de 2023, en una sala del Parlamento uruguayo varias autoridades y especialistas se reunieron para conversar de políticas públicas sobre suicidio. El encuentro se llamaba “El suicidio, una realidad que nos interpela”. Era abierto al público y buscaba poner el tema sobre la agenda. Glenda vio la convocatoria en Facebook y le llamó la atención. Por el tema y también por la coincidencia de la fecha. Ese día se cumplía un año del suicidio de su hija.

Glenda: Me interesaba saber qué se qué se iba a hacer. Yo lo que quería es que nadie pasara el dolor que yo estaba pasando. A mí, en ese momento, me dio impulso dentro de una gran depresión que yo tenía. Me llamó la atención, o sea, me hizo decir: “Me voy sola”. Voy hasta el Palacio Legislativo a ver de qué se trata esto, a ver qué va a pasar. O sea, cómo todo lo que a mí no me pudieron ayudar, cómo lo van a solucionar, qué se va a hacer.

Nausícaa: Glenda fue hasta el Palacio Legislativo, donde funciona el Parlamento uruguayo, y escuchó la presentación con atención.

Glenda: Y me acuerdo que yo me acerqué a los que estaban allí adelante cuando terminaron y rompí en llanto, pero desconsoladamente me puse a llorar porque en realidad no sé, no sabía por qué. O sea, sí sabía por qué era el dolor de hablar con alguien de lo que a mí me había pasado y fue ahí que conocí a estos compañeros de la campaña. Ellos me apañaron, me tomaron los datos, después se pusieron en contacto conmigo y bueno, fue allí que los conocí. Y después sí salió el proyecto de “La última foto”.

Nausícaa: La campaña de la instalación en la plaza Independencia que les contamos al comienzo del episodio. Glenda comenzó a participar en talleres de prevención del suicidio organizados por familiares y especialistas. Allí encontró un lugar para hablar del suicidio de su hija. Y también fue una oportunidad para ayudar a otros.

Glenda: Y para mí fue un proceso de iniciación a sanar, que de alguna manera no se sana nunca, pero el tratar de esta manera ayudar a otras personas fue como la salida que tuve de ese pozo en el que estaba en ese momento.

Nausícaa: Por eso dijo que sí enseguida cuando le propusieron participar en la exposición con la foto de su hija Melissa.

Glenda: El ver que la gente se cuestiona, el poner la problemática sobre la mesa, el poner a la vista las cifras, nomás, de suicidios que hay en nuestro país, y el no seguir ocultando ni las cifras ni los casos, para mí, es muy importante. Es como si lo estuviéramos poniendo sobre la mesa, y hay que buscar una solución y empezar con algo. Hay que empezar por hablarlo.

Nausícaa: En Uruguay hablamos poco de suicidio. Conversamos del tema en casos puntuales. Cuando se lanza una campaña de prevención, si se publican nuevos datos oficiales, ante el suicidio de alguna persona pública o si un caso llegó a la prensa.

Últimamente, por ejemplo, se ha cubierto bastante los casos de suicidios dentro de la policía, un grupo con una tasa altísima: 38 cada 100.000 habitantes. Casi duplica el promedio del país. Esto se asocia al estrés laboral, a la violencia diaria, a que tienen acceso a armas. También se habla de una mujer de 30 años que el año pasado se suicidó en la emergencia de un centro de salud mientras esperaba un psiquiatra. Había pedido ayuda varias veces.

Los especialistas dicen que el suicidio es un tema tabú en Uruguay, un problema invisible, silencioso.

Las gráficas oficiales muestran una tendencia histórica de aumento de suicidios, con algunos altibajos, un pico que sobresale en la pandemia del covid, y baja después de ella.

La mayoría de las personas que se suicidan son adultos mayores varones. La tasa más alta es entre los 75 y 79 años.

Pero los suicidios también son altos en las personas más jóvenes, en los adultos jóvenes, y en los adolescentes. Es la primera causa de muerte de los adolescentes.

Melissa, la hija de Glenda fue una de las adolescentes que se suicidó en 2022.

Le pregunté a Glenda cómo era su hija, qué cosas le gustaba hacer, y me contó que Melissa siempre fue amante de los animales.

Glenda: Desde chiquita, si estaba en el campo era a caballo. De las últimas salidas que hicimos, ella anduvo a caballo, que fuimos a festejar su cumpleaños y el de mi hermana. Anduvo a caballo, estuvo también entre animales en el campo. Bueno, dormía con los gatos. Era como parte de su ser. Ella veía un animal en la calle y bueno, de los que tenemos ahora, alguno me lo trajo ella de la calle. Ella lo veía, no podía dejar un animal abandonado en la calle.

Nausícaa: Cuando era una niña le gustaba el fútbol, ir al estadio con su madre a ver a Nacional, gritar los goles.

Glenda: Tenía eso de que cantaba, que gritaba, no le daba vergüenza nada. Era muy extrovertida, muy simpática, de tener muchos amigos. Entonces este, nada, eso.

Glenda identifica unos momentos clave, que afectaron a su hija. Cuando envenenaron a su perrita, la adolescencia, un proceso de depresión, la pandemia. Melissa se trataba con una psicóloga privada que pagaba su familia, y la psicóloga había aconsejado que además recibiera atención psiquiátrica. Glenda intentó conseguir un siquiatra en el mismo lugar que atendía su hija, pero fue difícil. En Uruguay se puede tardar meses para conseguir un turno con un psiquiatra, y una vez que se consigue un turno con uno es difícil conseguir el tratamiento con el mismo especialista. Además, las consultas suelen ser breves: una charla de unos 15-20 minutos, el ajuste o la repetición de la medicación y no mucho más.

Glenda: Iba con un psiquiatra, iba con otro, lo que llevaba a que tomara un tiempo sí, uno no. Al que iba le cambiaba, y después pasaba un tiempo, no la tomaba. Porque cuando conseguía la hora ya era otra medicación o retomar. Nunca llegó a una continuidad de seguir un tratamiento, porque si uno no es que tome un mes y llegue a hacer el efecto necesario. Ella tomaba ese mes y después, cuando conseguíamos hora para otro, para el médico, ya era como arrancar de cero de vuelta.

Nausícaa: Con esa inestabilidad, tampoco era fácil generar un vínculo de confianza con un médico. Después de probar varios, encontró uno con el que se sentía a gusto. Glenda me contó que un día Melissa lo fue a buscar.

Glenda: Ella quería recibir ayuda en ese momento. Ella se sentía cómoda con este psiquiatra, al punto de que un día lo fue a esperar a la puerta de la mutualista y él le dijo que bueno, que no la podía atender porque en ese momento era el director de la mutualista y que él no podía brindarle la atención. Y bueno, ahí fue el impasse a Salud Pública.

Nausícaa: Hasta los 18 años, Melissa se atendió en una mutualista, como le decimos en Uruguay al sistema privado de salud. Era gratis, por un convenio con el trabajo de Glenda. Pero el convenio duró hasta que cumplió 18. Entonces Melissa empezó a atenderse en el sistema público.

Era 2021 y llegó la pandemia. Melissa decía que se sentía mal, que necesitaba ayuda.

Glenda: El encierro, el estar sola, fue un agravante para la situación de ella. No conseguimos psiquiatra en ningún lado. La psicóloga un día me dijo: “Tiene que recibir atención psiquiátrica, esto es importante”. Y bueno, le expliqué que no habíamos podido encontrar, y me sugirió que fuéramos al Hospital Vilardebó, que ahí seguramente nos fueran a agendar.

Nausícaa: Es un hospital psiquiátrico de Montevideo, que es público, y complicado. Además de los pacientes usuales, derivan a pacientes de las cárceles o casos judiciales.

Glenda: Era un ambiente que no era para una gurisa de 19 años simplemente para adquirir una cita para psiquiatra.

Nausícaa: Es un edificio viejo, con sectores en mal estado, con problemas de higiene, falta de personal. Con frecuencia, los médicos denuncian que no alcanzan los psiquiatras, que no dan abasto, que no tienen las condiciones mínimas para atender a los pacientes. Glenda me contó cómo fue ir a este hospital con Melissa.

Glenda: Nos pasearon por todo el hospital, que no es acá, que es allá. Policía, con gente esposada, gente esposada sentada con el policía parado al lado, gritos. Ella, que en ese momento no estaba mal, se empezó a poner mal porque era un lugar espantoso. Se empezó a poner realmente de mal humor porque ella no quería estar ahí. Fuimos en teoría a la parte donde correspondía que nos dieran el número y casi que, entre risas, nos dijeron que para primera vez psiquiatra no iba a haber. No había, no existía esa posibilidad, que a lo sumo fuera a urgencias y que capaz que a la noche la iban a atender. Esto era de mañana. Eran las 11:00, las 10:00 y poco de la mañana. No cabía la posibilidad de que yo me quedara con ella para que la vieran en urgencias en ese momento, porque no era el caso. Nos fuimos.

Nausícaa: Pasaron los meses. Glenda no encontraba respuestas para su hija. Hasta que en enero de 2022, en una consulta de rutina de ginecología, Melissa le pidió ayuda a una doctora.

Glenda: Le plantea su situación de que no estaba pudiendo conseguir psiquiatra a esta doctora y esta doctora le consigue en enero una hora con psiquiatra para julio.

Nausícaa: Tenía que esperar seis meses.

Glenda: Melissa no llegó.

Nausícaa: Se suicidó el 22 de junio.

Glenda: Te queda eso de cómo puede ser. Alguien se preocupó por ella, sí. Una ginecóloga, en un control de rutina, se preocupó por ella. ¿Qué hubiera pasado si hubiera sido antes? O si… no lo sé. Si algo hubiera cambiado… no lo sé. Pero lo que sí sé es que no pueden pasar estas cosas, que los tiempos para pacientes que están en crisis o que necesitan ayuda en salud mental no pueden esperar tanto. La ayuda la necesitan ya.

Alguien que está pasando por una crisis o que tiene ideas suicidas no va a esperar tres meses. Y ya tres meses es mucho… pero seis. Es un tema muy delicado, que no, no puede dejarse estar tanto tiempo.

Nausícaa: Glenda cree que el suicidio está muy estigmatizado en Uruguay, que es un tema que nos cuesta mucho, que no hablamos. Le ha tocado vivirlo en su propia historia. Me contó que en su núcleo familiar más íntimo –su pareja, su otra hija– hablan todos los días de Melissa, la mencionan, la recuerdan. Pero al resto de su familia le cuesta mucho.

Glenda: Mis padres, mis hermanos… su forma, de repente, de lidiar con el dolor es no nombrarla. De repente, yo hablo en familia y me cambian de tema, y para mí es muy doloroso porque es como… es como culparla a ella de algo.

Y lo que una persona hace al quitarse la vida es no querer lidiar más con su dolor. Fue lo que pasó con mi hija. Ella lo que no quería era sufrir más, y el no nombrarla es como culparla. Culparla a ella y culparnos a nosotros como familia.

Y es todo lo contrario a lo que hay que hacer. Hay que tratar de hablarlo, tratar de ponerlo sobre la mesa y tratar de que esto no pase más. No nombrarlo no hace más que hacernos daño a los que estamos acá, a los que la peleamos día a día y a los que tratamos de estar sin ellos todos los días.

Si no lo hablamos, esto no va a parar. Pocas personas saben que somos de los países con las tasas de suicidio más altas del mundo. Un país chiquitito como el nuestro. Y el por qué no se habla… no lo sé. Pero, claramente, no está funcionando.

Silvia: Ya volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en el hilo.

No hay una explicación definitiva que aclare por qué Uruguay tiene una estadística tan alta de suicidios. Consultamos con varios especialistas, y todos coinciden en que es un fenómeno multicausal, complejo, que tiene que ver con la atención de la salud mental, la sociedad uruguaya, la cultura. Hay estudios, pero aún no hay una respuesta precisa que explique qué diferencia a Uruguay del resto de la región. Qué lo pone tan arriba en la lista de suicidios.

Sandra Romano: La verdad es que es una pregunta que me he hecho en forma individual y colectiva muchas veces. No tengo una respuesta clara para eso.

Silvia: Ella es Sandra Romano, psiquiatra y vicepresidenta de la Sociedad de Psiquiatría del Uruguay.

Sandra: Realmente es un problema importante en Uruguay. Hay algunos problemas que sí tienen que ver con las tasas de algunos problemas de salud mental, y con una atención no suficiente de estos problemas. Pero no es una explicación suficiente, porque muchas de las conductas suicidas, o mejor dicho, de los suicidios consumados también, no necesariamente se explican solo por ese lado. Entonces, bueno, es una pregunta pendiente. Yo no tengo una respuesta para eso.

Eliezer: Nausícaa nos sigue contando.

Nausícaa: Algunos especialistas sugieren explicaciones. Que los uruguayos no hablan de suicidio, ni de vejez ni de muerte, que son temas tabú. Que hay una cultura individualista y niveles muy altos de violencia, hacia niños y niñas, hacia las mujeres y hacia los más viejos. Que Uruguay es un país muy envejecido y que la vejez no se cuida. Que hay un consumo muy alto de alcohol y de pastillas, y una tendencia a psiquiatrizar los problemas.

En el caso de los jóvenes, Sandra también apunta a las expectativas y al sentimiento de fracaso.

Sandra: Creo que hay algo que tiene que ver con el lugar social también. Cuál es la expectativa respecto a la propia vida y qué es lo que esperan de la vida de uno, ¿no? Y qué posibilidad hay de acceder a eso. Ahí tenés, hay cosas que son bien distintas: lo que puede ser un joven, de un medio sociocultural medio o alto y las expectativas que hay depositadas en él, de lo que puede ser un joven de un medio sociocultural más carenciado. Las expectativas son diferentes y eso a veces implica presiones diferentes también. Igual se matan los dos grupos, ¿no?

Nausícaa: Sandra me dijo que esas expectativas pueden tener que ver con el rendimiento académico y profesional, o con el desempleo y las dificultades para lograr la independencia económica. Que la frustración puede ser un sentimiento muy típico de la adolescencia y de los jóvenes, pero está hablando de una experiencia más dura.

Sandra: Hay una cosa que puede ser la frustración. Casi te diría esa frustración enojada del adolescente. Y otra cosa es ese sentimiento de impotencia, de imposibilidad, de fracaso. El fracaso. El sentimiento de fracaso, de no llegar, de no dar la talla. Es mucho más duro. Es mucho más duro.

Nausícaa: Entre los jóvenes que se suicidan, la mayoría son varones.

Sandra: Los varones jóvenes piden menos ayuda que las mujeres. O hablan menos de sus cosas, ¿no? De sus dolores, de sus sufrimientos, de sus afectos. Creo que, en ese sentido, el patriarcado nos joroba a todos. A las mujeres es bastante claro. Pero creo que a los varones también, porque hay determinados mandatos sociales hacia los varones, que les limitan en su posibilidad de ser felices de alguna manera, ¿no? De acceder a admitir algunas cuestiones de su sensibilidad, de su afectividad, de no cumplir con algunos mandatos sociales y permitírselo. De no ser siempre exitosos, siempre poderosos, siempre… Que hay un mandato fuerte. Aún ahora uno dice: “las cosas cambiaron”. Sí, pero no tanto. Siguen estando presentes.

Yo creo que, en ese sentido, es interesante cuando uno piensa lo que son algunas cuestiones de los cambios respecto a las identidades de género en las mujeres. Es bastante claro para las mujeres jóvenes qué pueden ganar con estos cambios. Para los varones no es tan claro qué ganan. Si cambiamos determinadas cuestiones del orden social, ganamos todos. Y creo que eso no está bien transmitido todavía.

Nausícaa: Uno de cada cuatro adolescentes o jóvenes uruguayos dijo que al menos una vez en un año se sintió triste o desesperado, tanto que dejó de hacer sus actividades habituales. El dato es de la última Encuesta de juventudes, que estudia la salud mental y el bienestar de los adolescentes y jóvenes en el país. Encuestaron a casi 1000 personas. Un 12% dijo que pensó en el suicidio. Un 4% dijo que lo intentó.

La ansiedad y la depresión son los problemas de salud mental que más afectan a los jóvenes uruguayos. Para Sandra, esto podría relacionarse con las tasas altas de suicidio. También el consumo problemático de sustancias. Pero insiste en no simplificar: nunca son relaciones lineales, de causa efecto, siempre hay una historia particular y un contexto complejo.

Hay otro grupo muy afectado por los suicidios, y vale la pena hablar de esto un momento, porque nos da otras pistas sobre qué está detrás de estos números tan altos. Las estadísticas son claras: los adultos mayores, hombres, son los que más se suicidan en Uruguay.

La tasa de suicidio entre los 75 y 79 años es de 39 cada 100.000 personas. Recordemos, el promedio en Uruguay es de 21.

Sandra: Ahí una de las cosas que sí se plantea en general es todo el tema de la soledad, ¿no? La pérdida de redes, la pérdida de roles, digo, la pérdida de sentido. Digo, las ganas de vivir tienen que ver con el sentido de la vida también.

Nausícaa: La jubilación es un momento clave, porque se pierde el rol productivo, y muchas veces también se pierden vínculos y la vida social relacionada con el trabajo.

Sandra: En los varones, por ejemplo, muchas veces el rol de trabajador es lo fundamental y perder el rol del trabajador, el rol de proveedor, implica una pérdida importante de valor social, de valor personal también, ¿no? Y muchos no tienen intereses culturales, recreativos, deportivos, sociales, ¿no?

Nausícaa: Un informe sobre el suicidio en Uruguay apunta a la falta de conexión social en la vejez. Dice que la soledad crónica puede asociarse con ideas suicidas y que la prevención debería apuntar a reducir la soledad, a “mejorar las conexiones sociales y el sentido comunitario”.

El sociólogo Pablo Hein analizó 191 cartas de adultos uruguayos que se suicidaron entre 2004 y 2015. Estudiaron a quién se dirigían, los sentimientos que aparecían, los argumentos. Encontraron sentimientos de falta de esperanza, falta de sentido, agotamiento, problemas de salud física, deterioro. En menor medida, problemas económicos.

Esto escribió un hombre de 86 años: “En la vejez no tiene sentido existir, así que voy a terminar con esto. La soledad lo hace difícil. No quiero un cortejo fúnebre. Aquí están todos los documentos y los arreglos con la funeraria para que puedas encargarte. Quiero un ataúd cerrado y que me entierren en el cementerio del norte, cuanto antes mejor.”

Nausícaa: Históricamente, el suicidio en Uruguay ha sido masculino. Y la mirada de género puede ayudar a entenderlo. Como nos contaba antes Sandra sobre los hombres jóvenes, los varones hablan menos de lo que consideran que son sus debilidades…

Sandra: …El sufrimiento, la tristeza, algunas cuestiones de lo afectivo, y lo viven mucho más en soledad que las mujeres. Las mujeres tendemos a hablar más de lo que nos pasa. A los varones eso les cuesta mucho más. Y los deja más solos también, ¿no? El poder hablar de lo que a uno le pasa es algo que ayuda. Y los varones no hablan. Hablan menos.

Nausícaa: Esto coincide con las consultas al sistema de salud. Las mujeres suelen consultar más que los varones, no solo en salud mental. En temas de salud en general.

Pero como vimos en el caso de Melissa, con su madre yendo y viniendo buscando atención, hay varios problemas para conseguir ayuda médica en Uruguay. Le pregunté a Sandra cuáles son, desde su experiencia, las principales debilidades del sistema de salud uruguayo.

Sandra: Una de las cosas que creo que es importante es poder diferenciar entre lo que tiene que ver con prevenir las conductas suicidas y lo que es atender personas con conductas suicidas. Si bien son dos temas fuertemente relacionados, no son lo mismo.

Nausícaa: Para Sandra, la prevención de los suicidios no debería ser una tarea exclusiva del sistema de salud. Y tiene que ver con tender redes, comunidades.

Sandra: ¿Necesitamos mejores estrategias de atención? Sí, sin lugar a dudas. Pero no es suficiente. Y ahí sí pasa por estas otras cosas que hablábamos, ¿no? Cómo socialmente colaboramos a construir sentido.

Nausícaa: Sandra plantea que esto se logra con los vínculos. Los vínculos familiares, sociales, los grupos religiosos, los diferentes grupos de pertenencia, que dan identidad, sostén.

Sandra: Yo creo que entre los jóvenes eso es bastante claro. Pero eso es algo que necesitamos a lo largo de toda la vida, no solo cuando somos jóvenes.

Nausícaa: Esto es por fuera de la atención médica, para prevenir. Pero para tratar, hay que hablar de los que trabajan dentro del sistema, como los psiquiatras. Y Sandra resaltó que Uruguay es un país que tiene una tasa alta de psiquiatras. Según los datos de la OMS de 2016, es de 14 cada 100.000 personas, la segunda más alta de la región. Entonces, en principio el problema no sería la cantidad de psiquiatras.

Sandra piensa que se jerarquiza demasiado a los psiquiatras en la atención de la salud mental. Que son necesarios para casos específicos, pero no tienen que hacerse cargo de todas las situaciones. Le pedí un ejemplo.

Sandra: Imaginemos un caso. Alguien que perdió una persona querida y tiene un sufrimiento por eso. Un sufrimiento que se arrastró en el tiempo más de lo que uno supone que debería en un duelo cualquiera, ¿no? Puede consultar en el primer nivel de atención, y puede tener ahí un médico de familia, un médico generalista que evalúe la situación, una enfermera, un enfermero, que también trabajen con ese médico evaluando la situación, y ahí ver si necesita o no una consulta, por ejemplo, con un psicólogo, ¿no? Eso puede ser. Y que ahí evalúen si después si eso realmente constituye una patología como para que requiera un nivel de especializado de otra índole.

Nausícaa: Pero esto no suele ocurrir.

Sandra: Sigue la idea de que para atenderte la salud mental necesitas un psiquiatra.

Nausícaa: Le pregunté por los psicofármacos: qué pasa si el paciente necesita medicación. Sandra me dijo que, en el caso de Uruguay, los médicos que están en las policlínicas pueden recetar esta medicación y además, que los problemas más comunes de salud mental no necesitan psicofármacos.

Sandra: La depresión leve no requiere un antidepresivo, requiere otro tipo de estrategias. Algunas depresiones moderadas requieren antidepresivos y otras no, pero lo que sí requieren todas es un abordaje psicosocial con una mirada más amplia.

Nausícaa: Y aunque el problema no es la cantidad, con tanta demanda, los psiquiatras no alcanzan.

Sandra: Y eso hace que aquel que sí necesita un nivel de atención especializada muchas veces no llega al cupo.

Nausícaa: Según la normativa uruguaya, no deberían pasar más de 30 días para conseguir un especialista, pero en la práctica esto no suele cumplirse. El otro problema es el tiempo que atienden los psiquiatras a sus pacientes durante una consulta. Como ya vimos en el caso de Melissa: son 15, 20 minutos.

Sandra: Eso es gravísimo. Estamos de acuerdo. En algún momento se planteaban que las primeras veces, o sea, que cuando te vas a atender por primera vez, el tiempo de consulta sea más prolongado. En algunos lugares eso sigue siendo así, en otros lugares no. Lo que a mí me parece más grave es que para todos sean 15 minutos, ¿no? O sea, que vos digas, que no puedas tener una primera consulta de un paciente que no conoces en absoluto, puede llevarte una hora o incluso más. La persona llega, no te conoce, no sabe quién sos, ¿por qué va a confiar de entrada? O sea, tenés que establecer un clima que propicie un buen encuentro. Eso lleva un buen rato. Muchas veces es necesario entrevistar a alguien de la familia también. Eso también lleva un rato. Tenés que poder escuchar el tiempo que la persona necesite, aunque lo vayas acotando. Evaluar eso, pensar qué puede requerir, explicar qué es lo que le vas a proponer y por qué. Digo, todo eso lleva tiempo.

Nausícaa: Y como le pasó a Melissa, es difícil darle continuidad a los tratamientos médicos.

Sandra: Cualquier paciente grave que va a tener un tratamiento a largo plazo requiere que lo siga el mismo equipo en el largo plazo. El psiquiatra y el equipo que sea. Si no es como todas las veces, empezar de cero. Por más que esté el registro en la historia clínica, por más que… no es lo mismo, el vínculo ahí importa mucho y en eso estamos teniendo un problema.

Nausícaa: Sandra plantea que habría que mejorar el primer nivel de atención, el trabajo en las policlínicas, en los barrios. Esos equipos, que están en contacto cercano con los pacientes, que los conocen, deberían fortalecerse con psicólogos, trabajadores sociales, terapeutas. Y promover hábitos saludables, actividad física, cuidados. Esa también es una manera de prevenir.

En marzo asumió un nuevo gobierno en Uruguay. Consultamos al Ministerio de Salud Pública del período que terminó para saber qué medidas se tomaron durante esa gestión. Destacaron la digitalización de los registros de intentos de suicidio en las emergencias. Explicaron que antes se anotaba en papel y era muy complicado hacer un seguimiento de los casos. Además, se amplió la edad de atención psicológica y se quitó el costo a dos medicamentos antidepresivos de amplio uso. Se hicieron capacitaciones, campañas. También consultamos a la nueva ministra de Salud, Cristina Lustemberg, que asumió en marzo. Nos dijo que la infancia, la adolescencia y la salud mental van a ser “máximas prioridades” en su ministerio y que se va a reforzar el primer nivel de atención en los hospitales.

Eliezer: Vamos a hacer una pausa, y a la vuelta, Sandra nos habla sobre qué podemos hacer para ayudar cuando alguien cercano atraviesa una crisis. Ya volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo. Antes de la pausa, Sandra Romano, psiquiatra y vicepresidenta de la Sociedad de Psiquiatría del Uruguay, hablaba sobre algunas posibles razones detrás de la tasa tan alta de suicidios en el país, y los retos en el sistema de salud. Queríamos regresar a lo más cercano, lo más personal, a cómo podemos abordar en nuestro círculo estas situaciones tan complejas.

Nausícaa nos sigue contando.

Nausícaa: Le pregunté a Sandra qué le aconsejaría a una persona que tenga un ser querido, un familiar, un amigo atravesando una situación de crisis. Me dijo que lo primero es escuchar, que el otro sepa que no está solo. Y acompañarlo a que pida ayuda.

Sandra: Asegurar que uno está. Y a veces acompañar ahí no solo es… no es necesariamente hablar del problema, ¿no? A veces es poder pasar un rato en paz también, ¿no? Es poder acompañar en la vida en otras cosas ¿no? Hablar del problema todo el tiempo también agota. No tenés por qué abarcar todo tampoco, ¿no? Eso es otra cosa que es bien importante, porque pasa muchas veces con los familiares que sienten que tienen que hacer todo, ¿no? Y no tienen porqué hacer todo. Pueden hacer un poquito y que otro haga otro poquito. Pero es como cuando alguien tiene otro tipo de enfermedad, ¿no? O sea, hacerse cargo del todo en todo momento es casi imposible. A la consulta un día, otro te acompaña otro día. Uno se queda contigo de tarde y te prepara un tecito, una merienda. Charlan de cualquier cosa banal, por ejemplo. Miran juntos una serie, que sé yo, leen algo, escuchan una linda música. O nada, miran por la ventana al horizonte.

Nausícaa: Hablar es importante para todos. También para las personas con ideas suicidas. Sandra les aconseja que hablen, que pidan ayuda. Que se animen a consultar.

Sandra: Y a veces uno tiene la sensación de que lo que tiene que ver con el sufrimiento o con los problemas de salud mental alcanza con poner voluntad. No, no alcanza. No es un tema de voluntad o de desear otra cosa. Tengo que salir solo, por ejemplo, ¿no? Es algo que se dice muy frecuentemente: no ¿cómo voy a consultar si yo tengo que salir solo de esto? No, no, no tenés por qué salir solo.

Nausícaa: Sandra volvió a la importancia de las redes y los vínculos.

Sandra: Si vos tenés una red de contención en la que te permitas apoyarte, siempre va a ser más fácil acceder a una solución. Porque además, cuando uno se siente muy mal, también tiene menos recursos disponibles, ¿no? Uno en esas condiciones abandona hasta los cuidados más básicos, ¿no? Digo, levantarse a la hora que se tiene que levantar le cuesta. Mantener los cuidados personales de higiene, bañarse, comer en las horas que hay que comer, qué sé yo, dormir. Esas cosas están alteradas como ritmo biológico, pero también cuestan llevarlas a cabo, ¿no? Y eso hace que hasta la imagen personal, uno se mira y no se ve como quiere verse. Y eso es como un circulito que se retroalimenta, y en eso ahí los demás pueden ser un sostén importante. O lo son, en general. Cuando uno no los ve solo como un ojo de afuera que te censura o que te juzga, sino como alguien que te puede apoyar.

Nausícaa: Ha pasado un poco más de dos años desde el suicidio de Melissa. Le pregunté a Glenda qué cosas le hacen bien. Me dijo que se enfoca en su familia, en su hija Agustina, que tiene amigos, que hace terapia, que hace pequeños proyectos, pequeñas salidas en familia, que procura ayudar.

Glenda: Los primeros tiempos no podía, o sea, no había lo que me levantara. Pero, pero pude, digo, junté fuerzas. En realidad en familia, nosotros entre los tres nos dimos fuerza y salimos. El dolor está, el extrañar a mi hija está todos los días y a cada momento y en mi cabeza y en mi corazón todo el tiempo. No hay cosa que no me recuerde a ella. Todo me recuerda todo. Todo, todo. Yo entro a su cuarto y todo lo que hay, pero hasta las canciones, todo, todo, todo y hasta no hace mucho yo… Ellas tienen la voz muy parecida, y a veces me dice mamá, Agustina me dice mamá, y a mi me está llamando ella y se me para el corazón por un segundo. Y hasta hace poco me parecía que escuchaba el portón y era ella. Son cosas que van quedando, pero que de a poquito uno las va tratando de transformar, de que obviamente va a doler. Yo perdí una hija, no va a pasar de un día para el otro y no va a pasar nunca. Pero sí tratar de canalizarlo o tratando de ayudar a otro como hice yo. O transformándolo y buscando salidas en pequeñas cosas. Ya te digo, en salir, en buscar algo distinto, pero siempre buscar hacer algo que te saque de ese lugar, de esa tristeza profunda, profunda, transformar.

Nausícaa: La foto de Melissa recorrió el país con la campaña de “La última foto”. Hicieron charlas en centros culturales, teatros, salas de cine, hospitales, capillas. Glenda dice que generó mucho interés. Tanto, que a pedido de la gente hicieron más charlas de las que tenían planeadas y están planificando nuevos talleres. Me dijo que participar en esto fue como un salvavidas. Que le dio esperanza y la sensación de que quizás está salvando una vida.

Silvia: En nuestra página web, elhilo.audio, y en la descripción de este episodio puedes encontrar un enlace con información sobre cómo acceder a líneas telefónicas de atención psicológica desde diferentes países de la región.

Eliezer: Este episodio fue reportado y producido por Nausícaa Palomeque. Lo editamos Silvia, Daniel Alarcón y yo. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido es de Elías González, con música compuesta por él y por Rémy Lozano.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Natalia Ramírez, Juan David Naranjo Navarro, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Desirée Yépez y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres abrir el hilo para informarte en profundidad sobre los temas de cada episodio, puedes suscribirte a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

* The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Elías González: This episode addresses sensitive mental health topics, including suicide, which may be triggering and may not be suitable for all listeners. Please consider this message and listen at your own discretion. Thank you.

Silvia Viñas: It’s a gray May afternoon in 2024 in Montevideo, and in Independence Square, an emblematic square of the Uruguayan capital, there are cubes with photos of people who committed suicide. There are 11 large cubes, two meters by two meters, with 11 portraits: Joaquín, dressed in a karate uniform, 23 years old. Matías hugging a dog, 33 years old. Javier at the beach, 42. Lucas smiling, 16. Olga, also smiling, 66 years old.

Glenda Ghan: We don’t know why. We only know that they were feeling pain and could no longer continue with this life. The reason, each of them would know their own.

Eliezer Budasoff: She is Glenda Ghan, 43 years old, and has two daughters. One of the photos in the plaza is of one of them: Melissa. She died by suicide in June 2022. She was 19 years old.

In the photo, you see a young woman with large, dark eyes, looking seriously at the camera.

Glenda: It’s strange to walk in front of her photo because it seems like she’s always looking at you. And that was her gaze. Those big eyes. From wherever you are, it seems like she’s looking at you.

Eliezer: This installation in Independence Square is part of a campaign called “The Last Photo”. Family members of Uruguayans who died by suicide participated, along with social organizations, sociologists, psychologists, and psychiatrists. It’s a project that replicates an experience from the United Kingdom to prevent suicide and promote mental health. The central objective of the campaign in Uruguay is to talk about suicide.

Silvia: For the exhibition, they contacted survivors, as they usually call the family and friends of people who committed suicide. They invited them to participate, and those who accepted, were asked to share recent photos of their loved ones. Glenda chose several photos of her daughter: in family outings, with her sister Agustina, posing like a model, playing with her dogs.

Glenda: The photo they chose was from several photoshoots that my brother, who took the photo, did with her. It’s like she has a model’s gaze, though she wasn’t a model or anything. But like every girl, she liked taking photos, and sometimes they would spend a weekend going out and taking pictures with some background, and well, they chose this one.

Silvia: Glenda has wondered what her daughter would say about this project. If she would agree with sharing her story.

Glenda: And I believe yes, that she thinks this is good, that this is good, that no one else should go through the pain and what led her to take her own life. That’s what the photo tells me.

Eliezer: Welcome to El Hilo, a Radio Ambulante Studios podcast. I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: And I’m Silvia Viñas.

Uruguay has one of the highest suicide rates on the continent: 21 per 100,000 inhabitants. In the Americas, the rate is 9.

Today, we’ll explore why a country that is usually seen as a model of well-being and stability in the region has a suicide rate 300% higher than the average. What lies behind this figure and how is such a crisis addressed.

It is April 4, 2025.

Eliezer: Our producer, Nausícaa Palomeque, wanted to understand why her country has such a high suicide rate and reported on this topic from Montevideo. Nausícaa continues to tell us the story.

Nausícaa: In June 2023, several authorities and specialists gathered in a room of the Uruguayan Parliament to discuss public policies on suicide. The meeting was called “Suicide, a Reality That Challenges Us”. It was open to the public and sought to bring the topic to the agenda. Glenda saw the call on Facebook and it caught her attention. Because of the subject and also because of the date’s coincidence. That day marked one year since her daughter’s suicide.

Glenda: I was interested in knowing what was going to be done. What I wanted was for no one to go through the pain I was experiencing. At that moment, it gave me momentum within the deep depression I was in. It caught my attention, or rather, made me say: “I’ll go alone”. I’ll go to the Legislative Palace to see what this is about, to see what’s going to happen. In other words, how are they going to solve this issue, what will be done.

Nausícaa: Glenda went to the Legislative Palace, where the Uruguayan Parliament operates, and listened to the presentation attentively.

Glenda: I remember approaching those at the front when they finished and I broke down crying, utterly inconsolably, because in reality I didn’t know why. I mean, I did know why – it was the pain of speaking with someone about what had happened to me. And there is where I met the people behind the campaign. They supported me, took my information, later got in touch with me, and well, that’s where I met them. And afterwards, the “The Last Photo” project came about.

Nausícaa: The photo showcase in the Independence Square that we told you about at the beginning of the episode. Glenda began participating in suicide prevention workshops organized by family members and specialists. There she found a place to talk about her daughter’s suicide. And it was also an opportunity to help others.

Glenda: For me, it was a way to start healing, which you can never fully accomplish, but trying to help other people in this manner was like my way out of the pit I was in at that moment.

Nausícaa: That’s why she immediately agreed to participate in the exhibition with her daughter Melissa’s photo.

Glenda: Seeing people questioning, putting the problem on the table, exposing the suicide figures in our country, and no longer hiding either the statistics or the cases, is very important to me. It’s like we’re putting it on the table, and we need to find a solution and start somewhere. We have to start by talking about it.

Nausícaa: In Uruguay, we barely talk about suicide. We discuss the topic in specific cases. When a prevention campaign is launched, if new official data is published, when a public figure dies by suicide, or if a case reaches the press.

Lately, for example, suicide cases within the police have been covered extensively, a group with an extremely high rate: 38 per 100,000 inhabitants. Almost double the country’s average. This is associated with work stress, daily violence, and access to weapons. There’s also coverage and discussion over the case of a 30-year-old woman who killed herself last year in a health center emergency while waiting to see a psychiatrist. She had asked for help several times.

Specialists say that suicide is a taboo topic in Uruguay, an invisible, silent problem.

Official graphs show a historical trend of increasing suicides, with some ups and downs, a peak that stands out during the COVID pandemic, and a decline afterwards.

Most of the people who die by suicide are older adult males. The highest rate is between 75 and 79 years old.

But suicides are also high among younger people, young adults, and teenagers. It is the leading cause of death for teenagers.

Melissa, Glenda’s daughter, was one of the teenagers who died by suicide in 2022.

I asked Glenda what her daughter was like, what things she liked to do, and she told me that Melissa was always an animal lover.

Glenda: From a very young age, if she was in the countryside, she went on horseback rides. On one of our last outings, she rode horses when we went to celebrate her birthday and my sister’s birthday. She was among the animals in the countryside. Well, she slept with the cats. It was like part of her being. If she saw an animal in the street, well, some of the ones we have now, she brought them home from the street. She would see a stray animal and couldn’t bear to leave it there.

Nausícaa: When she was a child, she liked soccer, going to the stadium with her mother to watch Nacional, cheering for goals.

Glenda: She had this way of singing, shouting, nothing would embarrass her. She was very extroverted, very friendly, with many friends. So, yeah, that was her.

Glenda identifies some key moments that affected her daughter. When her dog was poisoned, adolescence, a process of depression, the pandemic. Melissa was seeing a private psychologist paid for by her family, and the psychologist had advised that she also receive psychiatric care. Glenda tried to find a psychiatrist in the same place where her daughter was being treated, but it was difficult. In Uruguay, it can take months to get an appointment with a psychiatrist, and once an appointment is secured with one, it’s hard to continue treatment with the same specialist. Additionally, consultations are usually brief: a 15-20 minute chat, medication adjustment or repetition, and not much more.

Glenda: She would go to one psychiatrist, then another, which meant she would take medication sometimes yes, sometimes no. One psychiatrist would change her medication, and then some time would pass and she wouldn’t take it. Because by the time she got an appointment, it was already a different medication or starting over. She never reached a continuity of treatment, because it’s not like you take medication for a month and you’re good. She would take it for a month, and then when we got an appointment with another doctor, it was like starting from zero again.

Nausícaa: With that instability, it wasn’t easy to generate a trust relationship with a doctor. After trying several, she found one with whom she felt comfortable. Glenda told me that one day Melissa went looking for him.

Glenda: She wanted to receive help at that moment. She felt comfortable with this psychiatrist, to the point that one day she went to wait for him at the door of the health center, and he told her that well, he couldn’t see her because at that moment he was the director of the health center and he couldn’t provide her with care. And well, that was the turning point to Public Health.

Nausícaa: Until she was 18, Melissa was treated in a mutualista, as we call the private health system in Uruguay. It was free, through an agreement with Glenda’s work. But the agreement lasted only until she turned 18. So Melissa started receiving care in the public system.

It was 2021 and the pandemic arrived. Melissa would say she felt bad, that she needed help.

Glenda: The lockdown, being alone, was an aggravating factor for her situation. We couldn’t find a psychiatrist anywhere. One day the psychologist told me: “She needs to receive psychiatric care, this is important.” Well, I explained that we hadn’t been able to find one, and she suggested we go to Vilardebó Hospital, that they would surely schedule an appointment there.

Nausícaa: It’s a psychiatric hospital in Montevideo, which is public, and complicated. In addition to the usual patients, they also handle patients from prisons or judicial cases.

Glenda: It was an environment that was not appropriate for a 19-year-old girl simply to get a psychiatrist appointment.

Nausícaa: It’s an old building, with sections in poor condition, with hygiene problems, lack of personnel. Frequently, doctors report that there aren’t enough psychiatrists, that they can’t keep up, that they don’t have the minimum conditions to attend to patients. Glenda told me how it was to go to this hospital with Melissa.

Glenda: They walked us all around the hospital, “it’s not here, it’s there”. Police, people in handcuffs, handcuffed people sitting with police standing beside them, screams. She, who at that moment wasn’t doing badly, started to get worse because it was a horrifying place. She started to get really in a bad mood because she didn’t want to be there. We went theoretically to the department where we were supposed to get a number, and almost laughing, they told us that it would be impossible to get an appointment with a psychiatrist right away. That the possibility didn’t exist, that at most she should go to the emergency room and maybe they’d see her at night. This was during the morning. It was 11:00 or 10:00 in the morning. There was no possibility for me to stay with her to have her seen in the emergency room at that moment. We left.

Nausícaa: Months passed. Glenda couldn’t find answers for her daughter. Until in January 2022, during a routine gynecology consultation, Melissa asked a doctor for help.

Glenda: She explains her situation to this doctor, that she couldn’t find a psychiatrist, and this doctor gets her a psychiatrist appointment in July.

Nausícaa: She had to wait six months.

Glenda: Melissa didn’t make it.

Nausícaa: She committed suicide on June 22.

Glenda: You’re left with this feeling of how could this be. Someone did care about her, yes. A gynecologist, in a routine check-up, cared about her. What would have happened if it had been earlier? Or if… I don’t know. If something had changed… I don’t know. But what I do know is that these things can’t happen, that the waiting times for patients in crisis or who need mental health help can’t be so long. They need help right now.

Someone going through a crisis or having suicidal thoughts isn’t going to wait three months. And three months is already too long… but six. It’s a very delicate issue that can’t be left waiting so long.

Nausícaa: Glenda believes that suicide is highly stigmatized in Uruguay, that it’s a topic we struggle with, that we don’t talk about. She has experienced this in her own story. She told me that in her most intimate family circle – her partner, her other daughter – they all talk about Melissa every day, mention her, remember her. But the rest of her family finds it very difficult.

Glenda: My parents, my siblings… their way, perhaps, of dealing with the pain is not to name her. Sometimes, I talk about her in front of them and they change the subject, and for me it’s very painful because it’s like… it’s like they are blaming her for something.

And what a person does when they take their own life is not want to deal with their pain anymore. That’s what happened with my daughter. She didn’t want to suffer more, and not naming her is like blaming her. Blaming her and blaming us as a family.

And it’s exactly the opposite of what should be done. We need to try to talk about it, try to put it on the table and try to make sure this doesn’t happen again. Not naming it only does more harm to those of us who are here, who fight day by day and who try to survive without them.

If we don’t talk about it, this won’t stop. Few people know that we are one of the countries with the highest suicide rates in the world. A tiny country like ours. And why don’t we talk about it? I don’t know. But, clearly, it’s not working.

Silvia: We’ll be right back.

Eliezer: We’re back on El hilo.

There’s no definitive explanation that clarifies why Uruguay has such high suicide rate. We consulted several specialists, and they all agree it’s a multicausal, complex phenomenon related to mental health care, Uruguayan society, and culture. There are studies, but there’s still no precise answer explaining what distinguishes Uruguay from the rest of the region. What puts it so high on the suicide list.

Sandra Romano: The truth is, it’s a question I’ve asked myself individually and collectively many times. I don’t have a clear answer for that.

Silvia: She is Sandra Romano, a psychiatrist and vice president of the Uruguayan Psychiatry Society.

Sandra: It’s truly an important problem in Uruguay. There are some issues related to mental health problem rates and insufficient attention to these problems. But it’s not a sufficient explanation, because many suicidal behaviors, or suicides, are not necessarily explained only by that. So, well, it remains an open question. I don’t have an answer to that.

Eliezer: Nausícaa continues to tell us.

Nausícaa: Some specialists suggest explanations. That Uruguayans don’t talk about suicide, old age, or death, which are taboo topics. That there’s an individualistic culture and very high levels of violence towards children, women, and the elderly. That Uruguay is a very aged country and the elderly are not taken care of. That there’s very high alcohol and pill consumption, and a tendency to psychiatrize problems.

In the case of young people, Sandra also points to expectations and feelings of failure.

Sandra: I think there’s something to do with social status as well. What are the expectations regarding one’s own life and what do they expect from one’s life, you know? And what possibility is there of accessing that. There you have things that are quite different: what might be a young person from a middle or high socio-cultural background and the expectations placed on them, compared to what might be a young person from a more disadvantaged socio-cultural background. The expectations are different and that sometimes implies different pressures as well. Though you have people committing suicide in both groups. Right?

Nausícaa: Sandra told me that these expectations might relate to academic and professional performance, or to unemployment and difficulties achieving economic independence. That frustration can be a typical feeling of adolescence and youth, but she’s talking about a harsher experience.

Sandra: There can be frustration. I would almost say that angry frustration of the teenager. And another thing is that feeling of helplessness, of impossibility, of failure. Failure. The feeling of failure, of not making it, of not measuring up. It’s much harder. It’s much harder.

Nausícaa: Among young people who die by suicide, most are males.

Young men ask for less help than women. Or they talk less about their things, right? About their pains, their sufferings, their affections. I believe that, in this sense, patriarchy screws us all. For women it’s quite clear. But I think for men too, because there are certain social mandates toward men that limit their ability to be happy in some way, right? To access and admit some issues about their sensitivity, their affectivity, to not fulfill some social mandates and allow themselves that. To not always be successful, always powerful, always… There is a strong mandate. Even now one says: “things have changed”. Yes, but not that much. They continue to be present.

I think, in that sense, it’s interesting when one thinks about some issues related to changes regarding gender identities in women. It’s quite clear for young women what they can gain with these changes. For men, it’s not so clear what they gain. If we change certain aspects of the social order, we all win. And I think that’s not well communicated yet.

Nausícaa: One in four Uruguayan adolescents or young people said that at least once in a year they felt sad or desperate, so much that they stopped doing their usual activities. This data comes from the latest Youth Survey, which studies mental health and wellbeing of adolescents and young people in the country. They surveyed almost 1,000 people. About 12% said they had thought about suicide. 4% said they had attempted it.

Anxiety and depression are the mental health problems that most affect young Uruguayans. For Sandra, this could be related to high suicide rates. Also problematic substance use. But she insists on not simplifying: these are never linear, cause-and-effect relationships; there’s always a particular story and a complex context.

There’s another group heavily affected by suicide, and it’s worth talking about this for a moment, because it gives us other clues about what’s behind these high numbers. The statistics are clear: older adult men are the ones who die by suicide the most in Uruguay.

The suicide rate between 75 and 79 years old is 39 per 100,000 people. Remember, the average in Uruguay is 21.

Sandra: One of the things that is generally raised there is the whole issue of loneliness, you know? The loss of networks, the loss of roles, I mean, the loss of meaning. I mean, the will to live is also related to the meaning of life.

Nausícaa: Retirement is a key moment, because one’s productive role is lost, and often social bonds and work-related social life are lost as well.

Sandra: For men, for example, often the role of worker is fundamental, and losing the role of worker, the role of provider, implies a significant loss of social value, of personal value as well, you know? And many don’t have cultural, recreational, sports, or social interests, you know?

Nausícaa: A report on suicide in Uruguay points to the lack of social connection in old age. It says that chronic loneliness can be associated with suicidal thoughts and that prevention should aim to reduce loneliness, to “improve social connections and community sense.”

Sociologist Pablo Hein analyzed 191 letters from Uruguayan adults who died by suicide between 2004 and 2015. They studied who the letters were addressed to, the feelings that appeared, the arguments. They found feelings of hopelessness, lack of meaning, exhaustion, physical health problems, and deterioration. To a lesser extent, economic problems.

This is what an 86-year-old man wrote: “In old age there is no point in existing, so I’m going to end this. Loneliness makes it difficult. I don’t want a funeral procession. Here are all the documents and arrangements with the funeral home so you can take care of it. I want a closed casket and to be buried in the north cemetery, the sooner the better.”

Nausícaa: Historically, suicide in Uruguay has been predominantly male. And a gender perspective can help us understand this. As Sandra was telling us earlier about young men, males talk less about what they consider to be their weaknesses…

Sandra: …Suffering, sadness, certain emotional matters, and they experience these much more in solitude than women do. Women tend to talk more about what happens to us. For men, this is much more difficult. And it leaves them more alone too, doesn’t it? Being able to talk about what one is going through is helpful. And men don’t talk. They talk less.

Nausícaa: This coincides with consultations in the healthcare system. Women tend to consult more than men, not only for mental health but for health issues in general.

But as we saw in Melissa’s case, with her mother going back and forth seeking care, there are several problems in obtaining medical help in Uruguay. I asked Sandra what, from her experience, are the main weaknesses of the Uruguayan health system.

Sandra: One of the important things is to differentiate between preventing suicidal behaviors and treating people with suicidal behaviors. While these two issues are strongly related, they are not the same.

Nausícaa: For Sandra, suicide prevention shouldn’t be an exclusive task of the health system. It’s about building networks, communities.

Sandra: Do we need better care strategies? Yes, without a doubt. But it’s not enough. And that’s where these other things we were talking about come in, right? How we socially collaborate to construct meaning.

Nausícaa: Sandra suggests this is achieved through relationships. Family and social bonds, religious groups, different belonging groups that provide a sense of identity and support.

Sandra: I think this is quite clear among young people. But this is something we need throughout our entire lives, not just when we’re young.

Nausícaa: This is outside of medical care, for prevention. But for treatment, we need to talk about those who work within the system, such as psychiatrists. And Sandra highlighted that Uruguay is a country with a high rate of psychiatrists. According to WHO data from 2016, it’s 14 per 100,000 people, the second highest in the region. So, in principle, the problem wouldn’t be the number of psychiatrists.

Sandra thinks that psychiatrists are placed too high in the mental health care system. They are necessary for specific cases, but they don’t have to take charge of all situations. I asked her for an example.

Sandra: Let’s imagine a case. Someone who lost a loved one and is suffering because of it. A suffering that has dragged on longer than one would expect in any normal grieving process, right? They can consult at the primary care level, and there they might have a family doctor, a general practitioner who evaluates the situation, a nurse who also works with that doctor assessing the situation, and then determine if they need a consultation with, for example, a psychologist. That can happen. And then they can evaluate if that really constitutes a pathology that requires a specialized level of another kind.

Nausícaa: But this doesn’t usually happen.

Sandra: The idea persists that to attend to your mental health, you need a psychiatrist.

Nausícaa: I asked her about psychopharmaceuticals: what if the patient needs medication. Sandra told me that, in Uruguay’s case, doctors at polyclinics can prescribe this medication and, moreover, the most common mental health problems don’t require psychopharmaceuticals.

Sandra: Mild depression doesn’t require an antidepressant; it requires other types of strategies. Some moderate depressions require antidepressants and others don’t, but what they all require is a psychosocial approach with a broader perspective.

Nausícaa: And although the problem isn’t the quantity, with so much demand, there aren’t enough psychiatrists.

Sandra: And this means that those who do need a level of specialized care often don’t get a spot.

Nausícaa: According to Uruguayan regulations, it shouldn’t take more than 30 days to get a specialist, but in practice, this is often not fulfilled. The other problem is the time psychiatrists spend with their patients during a consultation. As we already saw in Melissa’s case: it’s 15, 20 minutes.

Sandra: That’s extremely serious. We agree. At one point, it was suggested that the first few times, that is, when you’re being seen for the first time, the consultation time should be longer. In some places, this is still the case; in others, it’s not. What seems more serious to me is that for everyone it’s 15 minutes, right? I mean, you can’t have a first consultation with a patient you don’t know at all in just 15 minutes; it can take an hour or even more. The person arrives, doesn’t know you, doesn’t know who you are, why would they trust you right away? You need to establish an atmosphere that fosters a good encounter. That takes a good while. Often it’s necessary to interview someone from the family as well. That also takes time. You need to be able to listen for as long as the person needs, even if you guide the conversation. Evaluate that, think about what they might require, explain what you’re going to propose and why. I mean, all of that takes time.

Nausícaa: And as happened to Melissa, it’s difficult to give continuity to medical treatments.

Sandra: Any serious patient who is going to have long-term treatment requires that they be followed by the same team in the long term. The psychiatrist and whatever team is needed. Otherwise, it’s like starting from scratch every time. Even if there’s a medical record, even if… it’s not the same, the relationship matters a lot here, and we’re having a problem with that.

Nausícaa: Sandra suggests that the primary care level should be improved, the work in polyclinics, in neighborhoods. These teams, who are in close contact with patients, who know them, should be strengthened with psychologists, social workers, therapists. And promote healthy habits, physical activity, and self-care. That is also a way to prevent.

In March, a new government took office in Uruguay. We consulted the Ministry of Public Health from the ending period to find out what measures were taken during that administration. They highlighted the digitization of suicide attempt records in emergency rooms. They explained that before, it was noted on paper, and it was very complicated to follow up on cases. Additionally, the age range for psychological care was expanded, and the cost was removed for two widely used antidepressant medications. Training and campaigns were carried out. We also consulted the new Minister of Health, Cristina Lustemberg, who took office in March. She told us that childhood, adolescence, and mental health will be “top priorities” in her ministry and that the primary care level in hospitals will be reinforced.

Eliezer: We’re going to take a break, and when we return, Sandra will talk to us about what we can do to help when someone close to us is going through a crisis. We’ll be right back.

Silvia: We’re back on El hilo. Before the break, Sandra Romano, psychiatrist and vice-president of the Uruguayan Psychiatry Society, was talking about some possible reasons behind the country’s high suicide rate and the challenges in the health system. We wanted to take a look into this on a personal level, to how we can approach these complex situations in our circle.

Nausícaa continues telling us.

Nausícaa: I asked Sandra what she would advise someone who has a loved one, a family member, a friend going through a crisis situation. She told me that the first thing is to listen, to let the other person know they’re not alone. And to accompany them in seeking help.

Sandra: Ensure that you’re there. And sometimes accompanying them there is not just… it’s not necessarily talking about the problem. Sometimes it’s being able to spend a peaceful moment together too. It’s being able to accompany them in life in other things.Talking about the problem all the time is also exhausting. You don’t have to cover everything either. That’s another thing that’s really important, because it often happens with family members who feel they have to do everything, right? And they don’t have to do everything. They can do a little bit and someone else can do another little bit. But it’s like when someone has another type of illness. I mean, taking charge of everything at all times is almost impossible. One person accompanies them to the consultation one day, another accompanies them another day. Someone stays with you in the afternoon and prepares you some tea, a snack. They chat about any trivial thing, for example. They watch a show together, whatever, read something, listen to nice music. Or nothing, they look out the window at the horizon.

Nausícaa: Talking is important for everyone. Also for people with suicidal thoughts. Sandra advises them to talk, to ask for help. To dare to seek consultation.

Sandra: And sometimes one has the feeling that when it comes to suffering or mental health problems, it’s enough to just have willpower. No, it’s not enough. It’s not a matter of willpower or wishing for something else. I have to get out of this alone, for example, right? It’s something that is said very frequently: no, how am I going to consult if I have to get out of this alone? No, no, you don’t have to get out of it alone.

Nausícaa: Sandra returned to the importance of networks and bonds.

Sandra: If you have a support network that you allow yourself to lean on, it will always be easier to access a solution. Because also, when you feel very bad, you have fewer resources available. In those conditions, one abandons even the most basic care, right? I mean, getting up at the time you have to get up is difficult. Maintaining personal hygiene care, bathing, eating at the right times, whatever, sleeping. These things are altered as a biological rhythm, but they’re also hard to carry out. And that means that even your personal image, you look at yourself and don’t see yourself as you want to see yourself. And that’s like a little circle that feeds back on itself, and in that sense, others can be an important support. Or they are, in general. When you don’t see them just as an outside eye that censors or judges you, but as someone who can support you.

Nausícaa: It’s been a little over two years since Melissa’s suicide. I asked Glenda what things make her feel good now. She told me that she focuses on her family, on her daughter Agustina, that she has friends, that she goes to therapy, that she does small projects, small family outings, that she tries to help others.

Glenda: In the early days I couldn’t, I mean, there was nothing that would lift me up. But, I found strength. Actually as a family, the three of us gave each other strength and we got through it. The pain is there, missing my daughter is there every day and at every moment and in my head and in my heart all the time. There’s nothing that doesn’t remind me of her. Everything reminds me of everything. Everything, everything. I enter her room and everything that’s there, but even songs, everything, everything, everything and until not long ago I… They have very similar voices, and sometimes she says mom, Agustina says mom, and to me it’s her calling me and my heart stops for a second. And until recently I thought I heard the gate and it was her. These are things that remain, but that little by little one tries to transform, that obviously it will hurt. I lost a daughter, the pain won’t go away from one minute to the other, it will never pass. But yes, try to channel it or try to help others like I did. Or transforming it and looking for outlets in small things. As I said, in going out, in looking for something different, but always looking to do something that takes you out of that place, of that deep, deep sadness, transform.

Nausícaa: Melissa’s photo traveled around the country with the “The Last Photo” campaign. They held talks in cultural centers, theaters, cinemas, hospitals, chapels. Glenda says it generated a lot of interest. So much so that at people’s request they did more talks than they had planned and are planning new workshops. She told me that participating in this was like a lifesaver. That it gave her hope and the feeling that perhaps she is saving a life.

Silvia: On our website, elhilo.audio, and in the description of this episode, you can find a link with information on how to access psychological support hotlines from different countries in the region.

Eliezer: This episode was reported and produced by Nausícaa Palomeque. It was edited by Silvia, Daniel Alarcón, and me. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. The sound design is by Elías González, with music composed by him and by Rémy Lozano.

The rest of El hilo’s team includes Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Natalia Ramírez, Juan David Naranjo Navarro, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Desirée Yépez, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask you to join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to open the thread to inform yourself in depth about the topics of each episode, you can subscribe to our newsletter by entering elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it every Friday.

You can also follow us on our social networks. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook, and Threads. You can find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share the episodes.

Thanks for listening.