Premios

Grammy

Oscars

People’s Choice

Super Bowl

Bad Bunny

Latinos

Representación

Cultura

Hollywood

Televisión

Streaming

En plena temporada de premios y espectáculos masivos en Estados Unidos (los Globo de Oro, los Grammys, el Super Bowl, los Oscar), la industria del entretenimiento más importante del mundo decide quiénes merecen ser celebrados y reconocidos. Para los latinos, que están siendo criminalizados y perseguidos por el gobierno estadounidense, la representación adquiere otra dimensión este año. Desde el desdén en la alfombra roja a la película brasileña El agente secreto hasta el revuelo causado por Bad Bunny, esta semana hablamos con Yamily Habib, antropóloga e historiadora, editora en jefe de Mitú, para entender cómo Hollywood y las pasarelas entrenan la atención, señalan quién pertenece y de qué manera, y qué significa que alguien ocupe esos espacios sin encarnar un estereotipo o sin renunciar a su idioma.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Daniela Cruzat y Lisa Cerda -

Edición

Eliezer Budasoff, Silvia Viñas -

Verificación de datos

Desirée Yépez -

Producción digital

Samantha Proaño, Franklin Villavicencio, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Elías González -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

Fotografía

Getty Images / Kevin Mazur

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Eliezer Budasoff: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia Viñas: Y yo soy Silvia Viñas.

Audio de archivo, Oscars [en inglés]: And the Oscar goes to…

Audio de archivo, Golden Globes [en inglés]: …and the Golden Globe goes to…

Audio de archivo, Critics Choice [en inglés]: …and the Critics Choice is…

Audio de archivo, Grammys [en inglés]: …and the Grammy goes to…Bad Bunny!

Silvia: “La pantalla no solo entretiene, sino que también señala estatus y pertenencia: le enseña a la audiencia, de manera silenciosa, quién merece reverencia”. Esa frase es de un texto que publicó la periodista Yamily Habib en enero de este año para hablar de la entrega de los Critics Choice Awards, la ceremonia que inaugura lo que se conoce como “temporada de premios” en Estados Unidos.

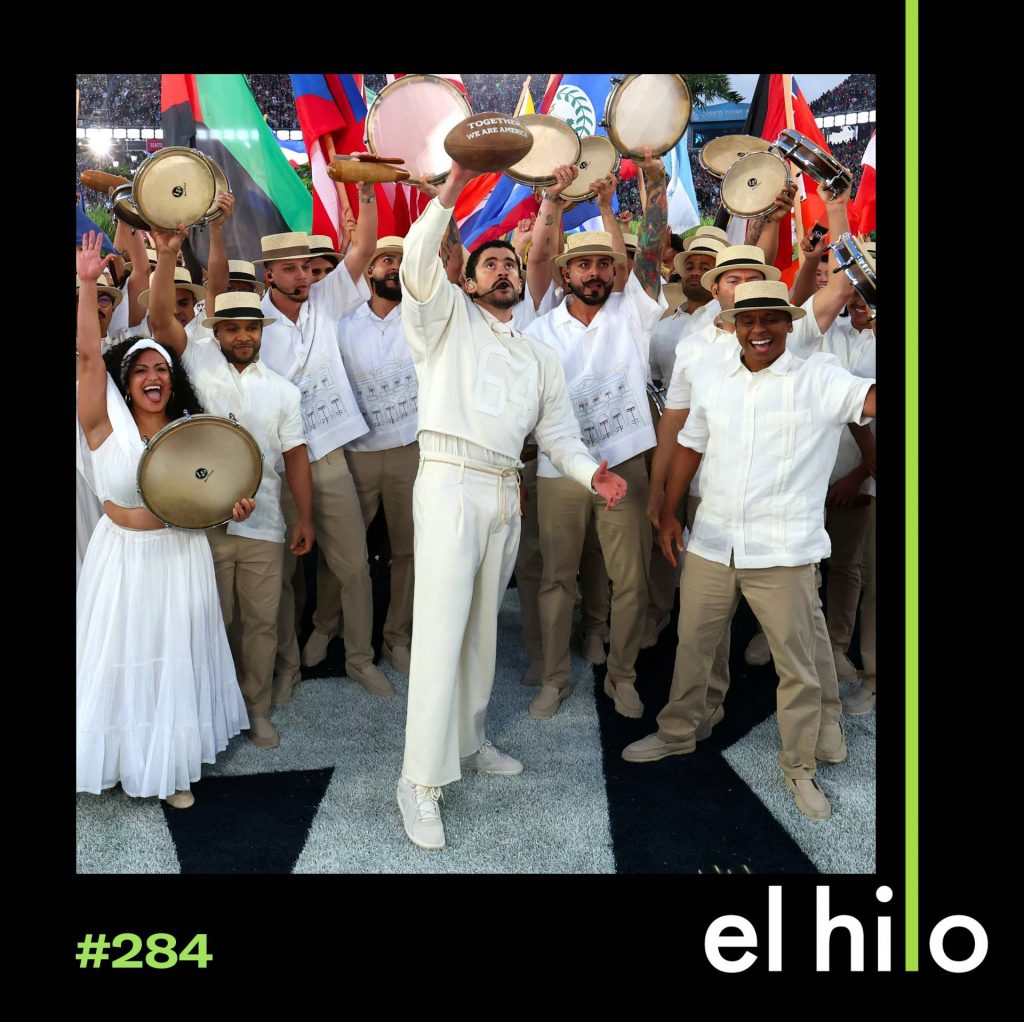

Eliezer: Ese texto habla de lo que pasó con la entrega del premio a Mejor película extranjera, una producción brasileña, en idioma portugués, que fue tratada de forma insultante. Pero esa fue solo la primera gran pasarela del año. En febrero, un disco completamente en español, el de Bad Bunny, ganó por primera vez la categoría “Mejor álbum del año” en los casi 70 años de historia de los Grammy. Y todavía no había pasado el show de medio tiempo del Super Bowl.

Silvia: Después de la presentación de Bad Bunny en el evento más importante del fútbol americano, esta semana, congresistas republicanos pidieron “multar” y “encerrar” al artista puertorriqueño, a ejecutivos de la NFL y a la Compañía Nacional de Radiodifusión por el contenido del show. El martes, uno de ellos dijo que era un gran día para, aquí cito: “reunir y deportar ilegales, especialmente aquellos a los que les gustó la obscenidad de Bad Bunny”.

Eliezer: Es ingenuo pensar que la representación de minorías en los escenarios más importantes de la industria del entretenimiento no tiene efectos sobre la vida de millones de personas, sobre todo si hablamos de comunidades que están siendo criminalizadas y perseguidas. Pero es complicado dimensionar qué significa ocupar esos espacios, a quién le sirve, y por qué debería importarnos.

Silvia: Sobre eso habló Eliezer con la antropóloga e historiadora Yamily Habib. Es la editora en jefe de Mitú, una de las mayores plataformas para latinos de Estados Unidos, donde escribe sobre política, género y temas de cultura popular.

Es 13 de febrero de 2026.

Eliezer: Hacemos una pausa y volvemos con la entrevista.

Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Yamily, estamos en medio de lo que se conoce como la temporada de premios en Estados Unidos, ¿no? Que empieza con los premios de la Crítica y sigue hasta mediados de marzo con los Oscar, pero en medio están también los Globos de Oro, los Grammy y el Super Bowl, y todo se siente un poco parte de lo mismo, ¿no? Así parece que se consume en América Latina como distintos escenarios de un mismo gran espectáculo. Me gustaría empezar por saber si también ves un poco estos espacios así, como parte de lo mismo y por qué son importantes. ¿Qué función cumplen y qué tienen en común o no?

Yamily Habib: Sí estoy de acuerdo con que cuando haces una seguidilla de eventos que terminan pareciéndose a lo mismo, es lo que yo digo, termina siendo un cassette. Se hace a propósito, una época del año donde se acumulan todas las views en televisión. Y lo importante de esto es que si bien es un espectáculo de entretenimiento, también pasa a ser una pasarela de muestras de representación de poder, que es lo que termina siendo la pasarela. La alfombra roja termina siendo una una manera de demostrar quién lleva la batuta en la representación. No hay mejor manera de controlar la formación de opinión de un público que a través de una pasarela, que a través de una vitrina donde yo te digo, lo mismo sucede con la moda, lo mismo sucede con absolutamente todo. Lo colocas en una pantalla y esto es lo que quizás deberías ponerte; esto es quizás la manera en la que deberías verte; esto es lo delgada que deberías estar; esto es… Cuando eso se hace de una manera masiva, un evento tras otro durante casi seis meses. Existe una narrativa por debajo que se vuelve muy evidente cuando te detienes dos segundos y empiezas a prestar atención.

Eliezer: Me gustaría que empecemos a hablar de la primera entrega de premios de este año, los de la crítica cinematográfica. Pasó algo que fue bastante increíble con el premio a la mejor película extranjera. Vos escribiste sobre eso y quería saber si puedes contar brevemente qué son estos premios, qué significan dentro de, de la pasarela de premios de Estados Unidos y ¿qué fue lo que pasó?

Yamily: Antes de, de entrar a ello, a mí me gusta siempre llamar la atención con la palabra de “crítico”. Todo lo que se ha hecho en la historia del arte ha estado narrado y construido gracias a los críticos. Muy pocas personas conocen la historia de que Picasso llegó a ser Picasso porque se hacía en una sala de críticos, en la casa de Gertrude Stein en París, donde la gente venía a decir este me gusta, este no me gusta. Y se empezaba a gestionar todos los círculos de reconocimiento que se llaman la Historia. Cuando tú hablas de que en un evento que es el de los críticos, los críticos son los que determinan quién es artista, quién no es artista, podemos tener esa discusión moral en otro momento, pero todos ellos tienen esa discusión, ellos tienen esa herramienta de poder.

Y cuando en un evento como los Critics Choice Awards, que son los premios de los críticos, eh, se espera el reconocimiento de las primeras películas que salieron el año anterior, las películas que están marcando… El crítico dice por qué esta película es buena o no y de repente el director Kleber Mendonça Filho se ve sorprendido en la alfombra roja por la presentadora de E! Entertainment Television…

Audio de archivo, E! Entertainment Television:

Presentadora: So I have a very special surprise for you. [Entrega un premio] Congratulations!

Yamily: Que le dice, en menos de un minuto, ganaste el premio a la Mejor película extranjera.

Audio de archivo, E! Entertainment Television:

Kleber Mendonça, director de The Secret Agent: Yeah?

Presentadora: You are winners tonight, baby! Winner! Did you have any idea?

Kleber Mendonça, director de The Secret Agent: No…

Presentadora: You had no idea? Oh my god. Congratulations!

Yamily: Te entrega el premio y vamos a corte. Estamos hablando de una película que no solo es muy poderosa y muy buena para quienes no la hayan visto. Es una película espectacular. Es una película extranjera, es una película en otro idioma y es una película que de repente esta pasarela de poder te dice: “No eres lo suficientemente importante como para estar en el escenario. Toma lo que te lo que te tenemos aquí, que te vaya muy bien y pasamos a otra cosa”. El mensaje que se pasa que, que eso transmite es: esto realmente no es tan importante. A mí lo que más me llamó la atención de todo eso es que el actor principal de la película, que es Wagner Moura. Él fue adorado por todo el mundo cuando él era Pablo Escobar, cuando él representó el cartel, cuando él representó este género que tiene tan obsesionados a los americanos. Todo el mundo lo alababa, él estaba en todas partes, era memes, era todo. Cuando él está haciendo un protagonista de una película que además se desarrolla en la época de la dictadura en Brasil, dictadura que todos sabemos que fue de injerencia americana dentro del continente suramericano, lo pasamos por debajo de la mesa. Hay otra circunstancia que debe estar, que creo que todo el mundo debe tener presente, y es que en este momento la política internacional es diferente a aquella época. En este momento, la política internacional se está yendo mucho más, yo creo que se pasó de la punta del barranco en la derecha y está todo el mundo intentando reconstruir la narrativa en torno otra vez a la hegemonía blanca. Y el cine lo que hace o la o estas pasarelas de control que yo llamo lo que ellas hacen, es no necesariamente cambiar las actitudes de la gente, pero cambiar la opinión primero y que tú hagas este gesto en esa pasarela es un indicativo súper importante de qué es lo que yo quiero que tú pienses a partir de este momento.

Eliezer: ¿Tú crees que esto que pasó en los premios de la Crítica, ¿se trata de una decisión deliberada, una o una decisión más inconsciente, más ideológica, sin que sea puesta en palabras o en planes? Por decirlo de otra manera, ¿es una empresa de entretenimiento que piensa que darle más espacio a una película que no es hablada en inglés le trae menos audiencia y menos dinero, o ni siquiera se detienen a hacer un cálculo? O sea, ¿cuán estructural es esto?

Yamily: Muy profundamente, yo creo que estas decisiones, y además teniendo diez años trabajando para Estados Unidos, nada está hecho al azar. Si bien la presentadora puede no haber tenido ninguna idea de lo que era, si no le dijeron: “Mire, tienes cinco segundos para hacer esto y pasas a lo siguiente”. Y ella no tenía una premeditación al respecto, sí, hay una estructura por encima que dice: “Necesitamos poner el foco aquí, movámonos de lado a esto”. Entonces yo creo que esto, todo forma parte del mismo síntoma. Y el inconsciente habla a veces mucho más alto que el consciente. Si esto hubiese sido inconscientemente, es una evidencia, aún así, de que hay una narrativa a la que nos queremos adherir a partir de ahora. En Estados Unidos en este momento, NPR, por ejemplo, que fue la National Public Radio PBS, por ejemplo, todo lo que está para hablarle a los demás, para hablar en comunidad, se les quitó todo el financiamiento.

Audio de archivo, EFE: El presidente de Estados Unidos, Donald Trump, firmó una orden ejecutiva que ordena suspender la financiación federal destinada a la radio pública, NPR, y la cadena de televisión PBS a las que acusa desde hace años de mantener un sesgo izquierdista.

Yamily: Entonces, todas estas empresas de entretenimiento como E! Entertainment, están peleando por los fondos, por el dinero, porque se les permita más tiempo en el aire en este momento político, y ellos tienen que adherirse de una u otra manera a lo que la gente de arriba está diciendo. Entonces, yo creo que es un poco de las dos cosas.

Eliezer: Ahora, ¿cuál es la situación real en este momento de los latinos actualmente en la industria cultural de Estados Unidos? ¿No? Porque por un lado tienes un gobierno que literalmente está cazando migrantes en las calles de distintas ciudades, ¿no?, De Estados Unidos y tienes reportes que dicen que la mayoría de las principales empresas multimedia del país han eliminado sus iniciativas de diversidad e inclusión en el primer año del gobierno de Trump, ¿no? Y por otro lado, tienes figuras que parecen como muy presentes o muy consagradas en la industria cultural de Estados Unidos. Tienes a Pedro Pascal, que es chileno, apareciendo, digamos, como protagónico en películas importantes y también en shows importantes. Tienes a Bad Bunny en el Halftime del Super Bowl, tienes a latinos como Guillermo del Toro y como Wagner Moura nominados al Oscar. Entonces cuesta difícil conciliar, como estas dos cosas, ¿no? Me gustaría un poco, si me puedes contar ¿cómo está en este momento la situación de representación de los latinos en Estados Unidos?

Yamily: Es muy interesante que menciones a Pedro Pascal, Bad Bunny, le vamos a poner un pin para hablar de eso aparte. Pero aún cuando nosotros como latinoamericanos reconocemos a quienes nos representan como Pedro Pascal, hace algunos algunas décadas era Edgar Ramírez, por ejemplo, el venezolano. Es importante saber que dentro de la gran escena que es el cine hollywoodense esta representación es menos del 5%. Ellos representan muy poco de 1,300 películas que se han hecho en los últimos años menos del 3% eran personas latinoamericanas, personas de color y esto delante de la cámara. Detrás de la cámara, la primera vez que directores latinoamericanos estuvieron reconocidos fue después del 2000, son Guillermo del Toro, los directores mexicanos.

Sí, para nosotros es muy importante, pero realmente no representa nada de lo que se representa en la gran maquinaria que es. Esa es la otra paradoja, la comunidad latina, la comunidad hispana es la que lleva la batuta en el consumo de streaming. Nosotros somos los que le damos audiencia a estas plataformas, pero no tenemos representación allí. Y ahí es cuando esta servidora siempre dice son mecanismos de control, si no nos tienen delante de la cámara, pero nos tienen ahí consumiendo, ¿qué es lo que quieren que hagamos? Entonces sí existe muchísimo talento latinoamericano en el cine actual, pero no está reconocido como cuando lo pones en perspectiva, realmente no está reconocido, no llega al 5% en total.

Cuando salieron películas con Zoe Saldaña, Salma Hayek siempre está por allí diciendo algo, Eva Longoria siempre es una, o sea siempre existe… No solo momentos muy puntuales para ello, sino que estas mujeres han sido hipersexualizadas y estas mujeres son latinas, no del todo blancas, no del todo negras. Entonces, si me permites hacer un poco el el recuento, porque yo creo que es importante que la gente sepa que la historia del cine, que Hollywood, el de hoy, no es actual. Esto es un fenómeno que tiene casi un siglo, más de un siglo en estructura.

El cine en Estados Unidos empezó a finales del siglo 19, el cine solo era para las personas que podían leer porque era cine mudo y habían las frases en la mitad, entonces solo la persona que podía leer podía entender. Y luego, cuando llega el cine sonoro, ya habían elementos de representación latinoamericanas, porque había habido la Revolución mexicana, la guerra entre México y Estados Unidos, y el mexicano siempre había sido el malo y la mujer era la señorita, la guapa, la hipersexualizada, pero nunca eran de color. Y las películas que se empezaron a estructurar en Estados Unidos a principios de siglo siempre eran para entretenimiento del blanco. Entonces el lugar que nos permiten a los latinos en cualquiera de estas narrativas es mientras entretenga a quien está en poder y normalmente, lo sabemos históricamente, el que está en poder siempre es el blanco. Entonces este momento de representación que estamos viviendo hoy en día, lamentándolo mucho, no es muy diferente de lo que ha sido en los últimos 50, 60 años.

Hollywood te dice qué es lo que deberías hacer y cuando te lo repite una y otra vez. Por eso los premios están seguidos uno detrás del otro. Es repetir, repetir, repetir hasta que te lo aprendas.

Eliezer: Una pausa y volvemos.

Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Uno tiene la impresión de que siempre hay una histeria detrás de la aparición de cualquier minoría en un espacio hegemónico blanco, heterosexual, ¿no? Hay una histeria si el personaje principal de La Sirenita es negra, hay una histeria si aparece una influencer trans en una publicidad de cerveza, hay una histeria porque uno puede elegir un personaje no binario en un videojuego, ¿no? Cuando uno ve estas polémicas que, que en los últimos años han aparecido un montón, es difícil no preguntarse de verdad ¿para quién es realmente un problema esto? Entonces te quería preguntar si tú crees que todas estas histerias que aparecen, si son de alguna manera, digamos, como una reacción literalmente al surgimiento de otro tipo de imágenes, de otro tipo de diversidad en los espacios de representación.

Yamily: Hay una, un momento de la historia de los premios de la Academia que que a mí siempre me viene a la cabeza. Es mi imperio romano. La primera mujer afroamericana en ganar un Oscar, era Hattie McDaniel. Ella ganó el Oscar en 1940, por “Lo que el viento se llevó”. En plena segregación, ella gana el Oscar, la reconocen, pero la tuvieron que sentar de lado. Ese momento en la historia a mí siempre se me ha quedado en la cabeza como: esta es la hipocresía, pero el, la génesis de la hipocresía televisada.

La primera latina Rita Moreno, Rita Moreno cuando gana el Oscar a mejor actriz de reparto, Supporting Actress. Ella gana por un papel en el que ella la obligaron a llenarse la la cara de tinte negro porque la actriz principal tenía que resaltar, tenía que ser la blanca.

Audio de archivo, Rita Moreno: They just threw you in this, and they put on some very dark makeup, and done.

Yamily: ¿Qué tanto ha cambiado hasta ahora en tantos años? Existe una incomodidad cuando llega una persona de color, cuando llega una persona diferente, porque esa persona amenaza al statu quo que le ha dado tanta facilidad y tanta comodidad a tantas personas.

Eliezer: Tú recién decías algo que me parece preciso y es como que Hollywood es una punta de lanza, digamos, ¿no? Como impone la narrativa, va diciendo quien pertenece y quien no va, digamos, entrenándonos también en esto, ¿no? Por un lado, pero por otro lado hay un reclamo que siempre ves por lo menos en los últimos años, desde la nueva derecha, de que Hollywood es un poco uno de los últimos refugios woke dentro de la industria cultural de Estados Unidos. ¿Cómo concilias estas dos cosas?

Yamily: Es el mismo tango de derecha a izquierda. Cuando tú tienes dos fuentes de poder absolutas para representar una pluralidad de tantas voces, terminan pareciéndose mucho. Porque es el amasar una cantidad de poder increíble entre dos facciones representando a un montón de gente. Harvey Weinstein es el síntoma más grande de todo ello.

Audio de archivo, EuroNews: Inicia en Nueva York el juicio contra el productor Harvey Weinstein, clave para el movimiento Me Too. Se le acusa de agresión sexual y violación, en total 5 delitos…

Audio de archivo, El Espectador: El ex productor de Pulp Fiction y Shakespeare enamorado, cuyas películas han ganado más de 80 premios Óscar, también fue declarado culpable de violación en el tercer grado…

Yamily: El abuso de mujeres, el maltrato de mujeres, la manipulación de los sistemas, todo dentro de una estructura que supuestamente es woke. La estructura más porosa o más abierta a la diversidad sigue siendo estructura.

Eliezer: Sí, ahora estamos hablando de dos cosas que me gustaría analizar contigo. Por un lado, de la representación de que exista una minoría, digamos, en pantalla y en segundo lugar, de, de qué forma existe esta minoría en la pantalla, ¿no? Cuando empiezan a aparecer primero, cuando empiezan a aparecer más latinos de la forma en que sea, ¿qué tuvo que pasar para que sucediera eso? ¿Fue un resultado de políticas públicas, de presión cultural, de un mercado que ya no podía ignorar esas audiencias, qué es lo que presiona para que aparezca?

Yamily: Desde un principio fue lo que a mí me gusta ver de parte del blanco. Sobre todo, yo siempre hablo de la hipersexualización, de la, de la mujer latinoamericana. Es el género pornográfico más buscado, latinas y lesbianas. Siempre ha sido para el placer del que lo está viendo. Entonces siempre han estado ahí para darme gusto. En el momento en el que empiezan a cambiar un poco las cosas es porque el pensamiento de los creativos y de los artistas, que siempre ha sido un colectivo bastante distinto históricamente empiezan a decir: “Vale, ¿y si colocamos este tipo de narrativas aquí? Si empezamos a mostrar…”.

Empezó a haber mucho cine independiente, latinoamericano en los años 80, y empezaron a haber actores y actrices; a mí me encanta siempre hablar de John Leguizamo. John Leguizamo en Romeo y Julieta, es uno de los primeros papeles en los que tú ves a un latino haciendo un papel exactamente igual que un blanco dentro de una narrativa, eso también se lo podemos atribuir a la belleza de Shakespeare. Pero él hace un papel allí por primera vez, en la que no hay una división, una fragmentación tan clara en que: “Ah, él es el latino de esta película”. Es la primera vez, al menos, me encantaría que alguien me corrigiera y que haya alguna alguna película antes, pero creo que ese es el primer momento en el que decimos: “Vale, los latinos pueden tener otro tipo de papeles”. Los años 80 y los años 90 hubo un cambio importante. sí lo hubo. ¿Qué estaba pasando en Estados Unidos y qué es lo más interesante? Estaba este eco de la época Reagan. Reagan fue el primero que dijo Make America great again.

Audio de archivo, Ronald Reagan: We’ll restore hope, and we’ll welcome them in a great national crusade to make America great again…

Yamily: Ese slogan fue de Reagan. Ese presidente americano impulsó nuevamente la familia, la unidad, la religión, el matrimonio heterosexual. Hubo una respuesta a su gobierno que fue la parte creativa de: Mira, pero sí, hay otros tipos de cosas”. Y luego viene la caída del Muro de Berlín. La caída del Muro de Berlín le hizo sentir Estados Unidos: “Va, les ganamos una”. Porque hasta ese momento ellos habían seguido haciendo como 50 películas de Vietnam, porque habían perdido esa guerra. Entonces estaban intentando decirle a todo el mundo: “Sí, la perdimos”. Pero realmente en este momento hay otro cambio de narrativa, hay una apertura a otro tipo de cosas. Sin embargo, de nuevo, y siempre lo voy a repetir, la representación sigue siendo ínfima.

Recuerdo que yo escribí un artículo sobre el por qué Frankenstein es tan buena película y yo cuando veías los comentarios en las redes sociales de cuando posteamos ese artículo, todo el mundo dijo: “No, no, pero te estás yendo muy lejos, te pasaste tres pueblos”. Yo digo que Frankenstein es buena por dos razones: uno, porque la historia la escribió una mujer. La historia original de Frankenstein está escrita por una mujer; y segundo, porque la película, la adaptación, está hecha por un latino. La belleza de Frankenstein, de la relación padre e hijo, sobre todo con la historia de Guillermo del Toro con su padre. La sensibilidad de esa película, la, la proximidad del personaje principal a una feminidad tan hermosa es lo que hace esa película tan potente y la gente no lo quiere ver. La gente ve al monstruo. La película es buena porque hubo monstruo, no. La película es buena porque es buena, porque hay diversidad dentro de la narrativa, que es una de las razones por las que Hollywood también se ha vuelto, entre comillas, muy aburrido. ¿Cuántos Avengers puedes ver?

Eliezer: Una pausa y volvemos.

Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Eliezer: Tú recién estabas hablando de que cuando empiecen a aparecer personajes latinos empiezan a aparecer solamente bajo determinado estereotipo, bajo determinado encuadre, ¿no? El problema es cuando esa inclusión se hace de una manera muy específica y en realidad al final termina encuadrándote, ¿no? Solamente te permite aparecer esto que tú decías hace un momento, solamente te permite aparecer dentro de determinados esquemas, ¿no? Incluso cuando este estereotipo es positivo, también es una caricatura. ¿Tú solamente puedes ser o el narco o el buen salvaje, digamos, ¿no? La mujer solamente puede ser o la puta o la esposa abnegada. Entonces, ¿cómo juega esto también en la configuración de las posibilidades de existir que tenemos dentro de una industria cultural?

Yamily: Corriendo el riesgo de sonar reduccionista, es la misma historia del vaso medio lleno o medio vacío. ¿Qué es mejor? Ese ha sido un discurso que yo he visto proliferar en todas las escenas desde la política pura con lo que pasó en Venezuela, que: “Bueno, pero por lo menos…”. O sea, vaso medio lleno o medio vacío. Aquí cabe perfectamente hablar de Bad Bunny. Bad Bunny te guste o no te guste su música, te guste o no te guste el reggaeton, te guste o no te guste la música puertorriqueña, sea cual sea tu punto de vista, el hecho de que un latino esté en el medio tiempo del evento más televisado en Estados Unidos dice muchísimo.

Audio de archivo, Apple Music Super Bowl Halftime Show: Qué rico es ser latino, ¡hoy se bebe!

Yamily: Sí había pasado antes, ya había pasado antes con Shakira, Jennifer López. Pero de nuevo era el mismo patrón. Era la mujer hipersexualizada que cualquier hombre blanco quiere ver mover el culo en un escenario. Estamos clarísimos y perdonen el francés.

Creo que lo que sucedió el domingo fue un, un espectáculo de sanación colectiva.

Audio de archivo, Apple Music Super Bowl Halftime Show: Bienvenidos a la fiesta más grande del mundo entero…

Yamily: Bad Bunny le respondió a la ínfima parte de la humanidad que insiste en dividir, que la única solución para los desacuerdos es el cariño y el amor. Lo hizo a través de una simbología no solo celebratoria de América Latina en general, de la comunidad en Estados Unidos, sino de todo el continente. No solo eso, sino que cerró su espectáculo dando una clase magistral de geografía sobre la definición de América que va desde la Patagonia hasta Canadá.

Audio de archivo, Apple Music Super Bowl Halftime Show: ¡God Bless America! Sea Chile, Argentina, Uruguay…United States, Canada, mi patria Puerto Rico…

Yamily: Y para todos los que lo observamos en tiempo real. Te guste o no te guste la música de Bad Bunny, entiendas o no entiendas lo que le está diciendo, el mensaje estaba muy claro. Somos muchos más los que abogamos por la unión y la celebración de los puntos en los que se unen nuestras diferencias, que las personas que insisten en politizar y radicalizar esas diferencias.

Musicalmente hablando, él celebró a las personas que venían antes de él, celebró su carrera, celebró a ese niño al que le entrega el Grammy, que era un reflejo de sí mismo cuando era pequeño y al mismo tiempo la simbología de haber puesto una boda en la mitad con Lady Gaga, que es el símbolo de la blanquitud, abrazándose, bailando. Ese guiño al niño que duerme sobre las dos sillas en una boda, fue una manera de decirle a todo el mundo: “Los latinos somos otra cosa.

Y lo otro que a mí me quedó muy claro fue que él celebra uno de los rasgos de la comunidad latina más importante es que, históricamente hemos recibido a todo el mundo, le hemos abierto los brazos a todo el mundo para decirles: “Ven y yo te enseño cómo como, ven y te invito a jugar dominó, ven y nos tomamos un cafecito”. Sin pedir nada a cambio, aún cuando eso sea ingenuo. Esa ha sido la tradición de los latinoamericanos con respecto al otro inmigrante. Fuimos un territorio que recibió a millones de personas desplazadas de Europa y siempre lo hicimos con brazos abiertos. Ahora la situación es diferente y él insiste en que nosotros seguimos siendo la misma comunidad.

Bad Bunny es un muchacho que salió de embolsar la compra en un supermercado y transformarse en un fenómeno. Se metió en un género que está también muy, muy manipulado. Es un género donde todos están muy empaquetados de la misma manera, tengas el talento que tengas, tienes que sonar de la exacta misma manera y tienes que ser el mismo tipo de producto. Bad Bunny hizo algo, es que él llegó y dijo: Y no me hace falta hablar inglés.

Audio de archivo, Vogue: A mí me gusta hablar en inglés en privado, no en las cámaras ni por ahí.

Yamily: No me hace falta adecuarme yo a tus códigos para ser el artista más reproducido en Asia, cuando no están entendiendo nada de lo que estoy diciendo. Es la autenticidad de ese muchacho. Es, creo yo, la señal de que hay una manera de hacer las cosas diferente. Podemos tener muchísimos desencuentros en gustos, pero él es un un gesto de decir: mira, estoy aquí. Ahora, que te pongas conspiranoico y digas: “esto es también un fenómeno construido por el poder hegemónico para…”. No sé cuántas veces nos pueden romper el corazón en un mes, ¿no? Pero creo que ese es un, un ejemplo, es decir, sí hay maneras de ir rompiendo con el con el discurso. Muy personalmente, ¿qué creo yo que hay que hacer para ayudar a empujar esta rueda de madera? Consumir más cine latinoamericano, consumir más literatura latinoamericana y leer historia, no preguntársela a chatGPT.

La historia tiene, lamentándolo mucho, la condena de repetirse, porque es el síntoma de la locura. Hacer las cosas una y otra vez, de la misma manera, esperando resultados diferentes. Esa es la condena de la historia. Nosotros estamos repitiendo formatos, pero con muchas otras herramientas. Entonces, yo creo que sí puede haber un cambio, pero empieza porque nosotros nos demos cuenta de que realmente no importa tanto lo que suceda en Hollywood cuando tenemos tan buen cine en América Latina, cuando tenemos tan buena literatura en América Latina. Hay maneras de nosotros darles la vuelta y decir: mira, realmente, si tengo mangos tan buenos en mi casa porque me voy a comprar uno artificial.

Eliezer: Lo que tú dices a mí me parece muy preciso, ¿no? Y es algo que en realidad las comunidades latinas, las sociedades de América Latina, se dicen a sí mismas, ¿no? Ahora, ¿cómo afectan igual estos patrones de representación o la ausencia de ellos en la manera en que las comunidades latinas se ven a sí mismas o son vistas por otros? Porque a pesar de esto que tú dices, a todos nos emociona que Bad Bunny esté ahí, a todos nos emociona que Pedro Pascal esté ahí. A todos nos emociona Guillermo del Toro. A todos nos emociona Wagner Moura. Entonces, ¿por qué es importante igual la representación en la industria cultural hegemónica de Estados Unidos?

Yamily: Porque si hemos pasado tantos años sin que nadie nos preste atención, tantos años siendo discriminados, tantos años considerándonos ciudadanos de segunda clase en el orden mundial, que alguien nos esté prestando atención sana algo en el inconsciente colectivo. Hay una parte de nosotros que dice: ¿viste?

Audio de archivo, La Clave: ¿Por qué amamos a Pedro Pascal? Porque, independientemente de que él se haya criado en Estados Unidos, realmente es de raíces chilenas y parece chileno y lo muestra con orgullo, y yo creo que somos tan egocéntricos o quizás necesitamos ese boost en nuestra autoestima…

Audio de archivo, EMBI: A pesar de haber tenido éxito en Hollywood y ser conocido prácticamente en todo el mundo, Guillermo del Toro no olvida sus raíces y no niega su mexicanidad.

Audio de archivo, Todo Noticias: El primer Óscar del país sudamericano se celebró como una Copa del Mundo. Muy orgullosa de ser brasileña, muy orgullosa de una película como esta que merece mucho.

Yamily: Creo que nos han enseñado como comunidades periféricas y yo lo hablo desde el punto de vista de la tradición árabe en mi familia, la tradición latina en mi familia; nos han enseñado tanto a odiarnos a nosotros mismos, a ser el eco de la discriminación en la cabeza. Que este tipo de representaciones, estos momentos sanan, pedazos muy pequeños, pero lo hacen. Yo creo que el latinoamericano tiene mucho trabajo por hacer en, en sanar el odio a sí mismo. Si nosotros empezamos a sanar ese pedazo de nosotros y lo, lo está diciendo una de las personas más cínicas que vas a conocer en la vida, si empezamos a sanar ese pedacito de nosotros y decir: “Mira, realmente no, no, no, no me importa si no me estás reconociendo, porque nosotros estamos haciendo otras cosas”. Pero también crear mercado para ello. Creo que es el momento en el que todo podría cambiar, en el momento en el que nosotros demos la espalda y digamos: “Mira, ¿sabes qué? Yo tengo mercado para mí, yo tengo cosas que quiero consumir para mí”. En el cine latinoamericano de los siglos, de los años 80 y los años 90, eso sucedió muchísimo. Nosotros teníamos muy buen cine, consumido por nosotros, hecho por nosotros, para nosotros, y que hablaba de cosas que estaban pasando en nuestra sociedad. Entonces, creo que eso es lo que está sucediendo. Nos hace sentir bien, nos hace sentir eufóricos porque sana un pedacito que está muy roto por dentro.

Eliezer: Tú crees que en esta época, que además uno accede a tanta información, de todas formas posibles, ¿no? Si de todos modos seguir apareciendo o aparecer en una pantalla sigue siendo importante para las personas que están más en los márgenes, en los márgenes geográficos, en los márgenes raciales y culturales, sigue siendo importante ¿y por qué?

Yamily: No, no voy a ser ingenua y decir que, que tenemos que dejar de ver TikTok, Instagram, Netflix y volver a… No, eh, somos muchísimos batallando muchísimas cosas al mismo tiempo. Y en las comunidades marginales la supervivencia, eh, eh, predomina, las comunidades marginales no tienen el privilegio de ponerse a filosofar sobre lo que debería ser, lo que debería consumir o no, porque no tienen el tiempo. Es importante tener esa representación, es importante vernos en las pantallas porque nos humaniza. El ver a una persona en la pantalla, reconoce su humanidad, reconoce que, que esa persona existe y eso es el principio de la convivencia humana. Que yo te reconozca a ti como ser humano. Entonces claro que sigue siendo importante y va a seguir siendo importante durante muchísimo tiempo. Lo que creo que se debe hacer es que las personas que tenemos estas herramientas para comunicar empecemos a cambiar un poco o a sembrar esa semilla de: “¿Y si lo hacemos diferente? ¿Si volvemos a traer otro tipo de narrativas para nuestras comunidades que no dependan tanto de la persona que está en la alfombra roja en los Oscar?”.

Eliezer: Yamily, muchísimas gracias por hacerte un tiempo para hablar con nosotros.

Yamily: No, no, muchísimas gracias a ustedes. Por favor, esto ha sido un honor.

Daniela Cruzat: Este episodio fue producido por Lisa Cerda y por mí, Daniela Cruzat. Lo editaron Eliezer y Silvia. Desirée Yépez hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido es de Elías González y la música es de él y Rémy Lozano.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Jesus Delgadillo, Samantha Proaño, Franklin Villavicencio, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Elsa Liliana Ulloa y Daniel Alarcón. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Eliezer Budasoff: Welcome to El Hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia Viñas: And I’m Silvia Viñas.

Archival audio, Oscars [in English]: And the Oscar goes to…

Archival audio, Golden Globes [in English]: …and the Golden Globe goes to…

Archival audio, Critics Choice [in English]: …and the Critics Choice is…

Archival audio, Grammys [in English]: …and the Grammy goes to…Bad Bunny!

Silvia: “The screen doesn’t just entertain, it also signals status and belonging: it silently teaches the audience who deserves reverence.” That phrase is from an article published by journalist Yamily Habib in January of this year to discuss the Critics Choice Awards ceremony, which inaugurates what is known as “awards season” in the United States.

Eliezer: That article talks about what happened with the Best Foreign Film award, a Brazilian production in Portuguese, which was treated insultingly. But that was just the year’s first major showcase. In February, a completely Spanish-language album, Bad Bunny’s, won the “Album of the Year” category for the first time in the nearly 70-year history of the Grammys. And the Super Bowl halftime show hadn’t even happened yet.

Silvia: After Bad Bunny’s performance at the biggest American football event, this week, Republican congressmen called to “fine” and “lock up” the Puerto Rican artist, NFL executives, and the National Broadcasting Company for the show’s content. On Tuesday, one of them said it was a great day too, I quote: “round up and deport illegals, especially those who enjoyed Bad Bunny’s obscenity.”

Eliezer: It’s naive to think that the representation of minorities on the most important stages of the entertainment industry doesn’t have effects on the lives of millions of people, especially when we’re talking about communities that are being criminalized and persecuted. But it’s complicated to measure what it means to occupy those spaces, who it serves, and why it should matter to us.

Silvia: Eliezer spoke about this with anthropologist and historian Yamily Habib. She’s the editor-in-chief of Mitú, one of the largest platforms for Latinos in the United States, where she writes about politics, gender, and popular culture topics.

It’s February 13, 2026.

Eliezer: We’ll take a break and be back with the interview.

We’re back on El Hilo.

Eliezer: Yamily, we’re in the middle of what’s known as awards season in the United States, right? It starts with the Critics’ awards and continues until mid-March with the Oscars, but in between are also the Golden Globes, the Grammys, and the Super Bowl, and it all feels a bit like part of the same thing, doesn’t it? It seems to be consumed in Latin America as different stages of one big spectacle. I’d like to start by knowing if you also see these spaces a bit like that, as part of the same thing, and why they’re important. What function do they serve and what do they have in common or not?

Yamily Habib: Yes, I agree that when you have a series of events that end up looking like the same thing, it’s what I call a loop. It’s done on purpose, a time of year where all the TV views accumulate. And what’s important about this is that while it’s an entertainment spectacle, it also becomes a showcase of displays of representation of power, which is what the showcase ends up being. The red carpet ends up being a way to demonstrate who’s leading the charge in representation. There’s no better way to control the formation of public opinion than through a showcase, through a display window where I tell you—the same thing happens with fashion, the same thing happens with absolutely everything. You place it on a screen and this is what perhaps you should wear; this is perhaps the way you should look; this is how thin you should be; this is… When this is done on a massive scale, one event after another for almost six months. There’s a narrative underneath that becomes very evident when you stop for two seconds and start paying attention.

Eliezer: I’d like us to start talking about this year’s first awards ceremony, the film critics’ awards. Something quite incredible happened with the Best Foreign Film award. You wrote about it and I wanted to know if you can briefly tell us what these awards are, what they mean within the U.S. awards showcase, and what happened?

Yamily: Before getting into that, I always like to draw attention to the word “critic.” Everything that’s been done in art history has been narrated and constructed thanks to critics. Very few people know the history of how Picasso became Picasso because it happened in a room of critics, at Gertrude Stein’s house in Paris, where people would come to say I like this one, I don’t like this one. And all the circles of recognition that are called History began to take shape. When you talk about an event that belongs to the critics, the critics are the ones who determine who is an artist, who is not an artist—we can have that moral discussion another time, but all of them have that discussion, they have that tool of power.

And when at an event like the Critics Choice Awards, which are the critics’ awards, recognition is expected for the first films that came out the previous year, the films that are making their mark… The critic says why this film is good or not, and suddenly director Kleber Mendonça Filho is surprised on the red carpet by the E! Entertainment Television host…

Archival audio, E! Entertainment Television:

Host: So I have a very special surprise for you. [Hands over an award] Congratulations!

Yamily: Who tells him, in less than a minute, you won the Best Foreign Film award.

Archival audio, E! Entertainment Television:

Kleber Mendonça, director of The Secret Agent: Yeah?

Host: You are winners tonight, baby! Winner! Do you have any ideas?

Kleber Mendonça, director of The Secret Agent: No…

Host: You had no idea? Oh my god. Congratulations!

Yamily: They handed him the award and we cut it away. We’re talking about a film that’s not only very powerful and very good for those who haven’t seen it. It’s a spectacular film. It’s a foreign film, it’s a film in another language, and it’s a film that suddenly this power showcase tells you: “You’re not important enough to be on stage. Take what we have here for you, good luck, and let’s move on to something else.” The message that gets transmitted is: this isn’t really that important. What caught my attention most about all of this is that the film’s lead actor is Wagner Moura. He was adored by everyone when he was Pablo Escobar, when he represented the cartel, when he represented this genre that has Americans so obsessed. Everyone praised him, he was everywhere, he was memes, he was everything. When he’s playing a protagonist in a film that also takes place during the dictatorship era in Brazil—a dictatorship that we all know was of American interference within the South American continent—we brush it under the table. There’s another circumstance that should be, that I think everyone should keep in mind, and that is that at this moment international politics is different from that era. At this moment, international politics is going much further—I think the whole world is attempting to reconstruct the narrative back to white hegemony. And what cinema does or what these control showcases that I call them do, is not necessarily change people’s attitudes, but change opinion first and when you make this gesture on that showcase it’s a very important indication of what I want you to think from this moment on.

Eliezer: Do you think what happened at the Critics’ awards was a deliberate decision, or a more unconscious, more ideological decision, without it being put into words or plans? In other words, is it an entertainment company that thinks giving more space to a film that’s not spoken in English brings less audience and less money, or do they not even stop to make that calculation? That is, how structural is this?

Yamily: Very deeply, I believe these decisions—and I say this after having ten years working for the United States—nothing is done by chance. While the host may not have had any idea what it was, if they didn’t tell her: ‘Look, you have five seconds to do this and move on to the next thing.’ And she had no premeditation about it, yes, there is a structure above that says: ‘We need to put the focus here, let’s move to the side on this.’ So I think all of this is part of the same symptom. And the unconscious sometimes speaks much louder than the conscious. If this had been unconscious, it’s still evidence that there’s a narrative we want to adhere to from now on. In the United States right now, NPR, for example, which was National Public Radio, PBS, for example, everything that’s meant to speak to others, to speak in community, they’ve had all their funding taken away.

Archival audio, EFE: The President of the United States, Donald Trump, signed an executive order suspending federal funding for public radio, NPR, and the PBS television network, which he has accused for years of maintaining a leftist bias.

Yamily: So, all these entertainment companies like E! Entertainment are fighting for funds, for money, so they can be allowed more airtime in this political moment, and they have to adhere in one way or another to what the people above are saying. So I think it’s a bit of both.

Eliezer: Now, what’s the current real situation for Latinos in the U.S. cultural industry right now? Because on one hand you have a government that’s literally hunting migrants in the streets of different cities in the United States, and you have reports saying that most of the country’s major multimedia companies have eliminated their diversity and inclusion initiatives in the first year of Trump’s government, right? And on the other hand, you have figures who seem very present or very established in the U.S. cultural industry. You have Pedro Pascal, who’s Chilean, appearing as a lead in important films and also in important shows. You have Bad Bunny at the Super Bowl Halftime, you have Latinos like Guillermo del Toro and Wagner Moura nominated for Oscars. So it’s difficult to reconcile these two things, right? I’d like to know if you can tell me, what’s the situation of Latino representation in the United States right now?

Yamily: It’s very interesting that you mention Pedro Pascal, Bad Bunny, let’s put a pin in that to talk about it separately. But even when we as Latin Americans recognize those who represent us like Pedro Pascal, a few decades ago it was Edgar Ramírez, for example, the Venezuelan. It’s important to know that within the big scene that is Hollywood cinema this representation is less than 5%. They represent very little of 1,300 films that have been made in recent years; less than 3% were Latin American people, people of color and this in front of the camera. Behind the camera, the first time Latin American directors were recognized was after 2000, they’re Guillermo del Toro, the Mexican directors.

Yes, it’s very important to us, but it really doesn’t represent anything of what is represented in the big machine that it is. That’s the other paradox, the Latino community, the Hispanic community is the one leading the charge in streaming consumption. We’re the ones who give these platforms their audience, but we don’t have representation there. And that’s when I always say they’re control mechanisms, if they don’t have us in front of the camera, but they have us there consuming, what do they want us to do? So yes, there’s a lot of Latin American talent in current cinema, but it’s not recognized when you put it in perspective, it really isn’t recognized, it doesn’t even reach 5% in total.

When films come out with Zoe Saldaña, Salma Hayek is always there saying something, Eva Longoria is always one, I mean there’s always… Not only very specific moments for them, but these women have been hypersexualized and these women are Latinas, not entirely white, not entirely Black. So, if you’ll allow me to give a bit of a recount, because I think it’s important for people to know that the history of cinema, that today’s Hollywood, isn’t current. This is a phenomenon that has almost a century, more than a century in structure.

Cinema in the United States began at the end of the 19th century, cinema was only for people who could read because it was silent film and there were sentences in the middle, so only the person who could read could understand. And then, when sound cinema arrives, there were already elements of Latin American representation, because there had been the Mexican Revolution, the war between Mexico and the United States, and the Mexican was always the bad guy and the woman was the señorita, the pretty one, the hypersexualized one, but they were never of color. And the films that began to be structured in the United States at the beginning of the century were always for the entertainment of white people. So the place they allow us Latinos in any of these narratives is as long as it entertains whoever is in power and normally, we know historically, the one in power is always white. So this moment of representation we’re experiencing today, regrettably, is not very different from what it has been for the last 50, 60 years.

Hollywood tells you what you should do and when it repeats it to you over and over. That’s why the awards are one after another. It’s repeating, repeating, repeating until you learn it.

Eliezer: A pause and we’ll be back.

We’re back on El Hilo.

One has the impression that there’s always hysteria behind the appearance of any minority in a hegemonic white, heterosexual space, right? There’s hysteria if the main character of The Little Mermaid is Black, there’s hysteria if a trans influencer appears in a beer commercial, there’s hysteria because you can choose a non-binary character in a video game, right? When you see these controversies that have appeared a lot in recent years, it’s hard not to really wonder who is this really a problem for? So I wanted to ask you if you think all these hysterias that appear, if they’re in some way a reaction literally to the emergence of other types of images, other types of diversity in representation spaces.

Yamily: There’s a moment in the history of the Academy Awards that always comes to mind. It’s my Roman empire. The first African American woman to win an Oscar was Hattie McDaniel. She won the Oscar in 1940, for “Gone with the Wind.” In the middle of segregation, she wins the Oscar, they recognize her, but they have to seat her to the side. That moment in history has always stuck in my head as: this is hypocrisy, but the genesis of televised hypocrisy.

The first Latina Rita Moreno, Rita Moreno when she wins the Oscar for best supporting actress, Supporting Actress. She wins for a role in which they forced her to cover her face with dark makeup because the lead actress had to stand out, and had to be white.

Archival audio, Rita Moreno: They just threw you in this, and they put on some very dark makeup, and done.

Yamily: How much has changed until now in so many years? There is discomfort when a person of color arrives, when a different person arrives, because that person threatens the status quo that has given so much ease and so much comfort to so many people.

Eliezer: You were just saying something that seems precise to me and it’s like Hollywood is a spearhead, let’s say, right? Like it imposes the narrative, it’s saying who belongs and who doesn’t, let’s say, also training us in this, right? On one hand, but on the other hand there’s a complaint that you always see at least in recent years, from the new right, that Hollywood is kind of one of the last woke refuges within the U.S. cultural industry. How do you reconcile these two things?

Yamily: It’s the same tango from right to left. When you have two absolute sources of power to represent a plurality of so many voices, they end up looking a lot alike. Because it’s amassing an incredible amount of power between two factions representing a lot of people. Harvey Weinstein is the greatest symptom of all of this.

Archival audio, EuroNews: The trial against producer Harvey Weinstein, key to the Me Too movement, begins in New York. He is accused of sexual assault and rape, a total of 5 crimes…

Archival audio, El Espectador: The former producer of Pulp Fiction and Shakespeare in Love, whose films have won more than 80 Oscar awards, was also found guilty of rape in the third degree…

Yamily: The abuse of women, the mistreatment of women, the manipulation of systems, all within a structure that is supposedly woke. The most porous or most open structure to diversity is still structure.

Eliezer: Yes, now we’re talking about two things that I’d like to analyze with you. On one hand, the representation that a minority exists, let’s say, on screen and secondly, in what way this minority exists on screen, right? When they first start to appear, when more Latinos start to appear in whatever way, what had to happen for that to occur? Was it a result of public policies, cultural pressure, a market that could no longer ignore those audiences, what pressures for it to appear?

Yamily: From the beginning it was what I liked to see from the white perspective. Above all, I always talk about the hypersexualization of the Latin American woman. It’s the most searched pornographic genre, Latinas and lesbians. It’s always been for the pleasure of the one watching it. So they’ve always been there to please me. The moment things start to change a little is because the thinking of creatives and artists, which has always been a fairly different collective historically, starts to say: “Okay, what if we place these types of narratives here? If we start showing…”

There started to be a lot of independent, Latin American cinema in the 80s, and there started to be actors and actresses; I always love to talk about John Leguizamo. John Leguizamo in Romeo and Juliet, is one of the first roles in which you see a Latino playing a role exactly like a white person within a narrative, we can also attribute that to the beauty of Shakespeare. But he plays a role there for the first time, in which there isn’t such a clear division, such a clear fragmentation that: “Ah, he’s the Latino in this film.” It’s the first time, at least, I’d love for someone to correct me and if there’s any film before, but I think that’s the first moment in which we say: “Okay, Latinos can have other types of roles.” The 80s and 90s there was an important change, yes there was. What was happening in the United States and what’s most interesting? There was this echo of the Reagan era. Reagan was the first one to say Make America great again.

Archival audio, Ronald Reagan: We’ll restore hope, and we’ll welcome them in a great national crusade to make America great again…

Yamily: That slogan was Reagan’s. That American president once again promoted family, unity, religion, heterosexual marriage. There was a response to his government which was the creative part of: “Look, but yes, there are other types of things.” And then comes the fall of the Berlin Wall. The fall of the Berlin Wall made the United States feel: “Okay, we beat them at one.” Because until that moment they had continued making like 50 Vietnam films, because they had lost that war. So they were trying to tell everyone: “Yes, we lost it.” But really at this moment there’s another narrative change, there’s an opening to other types of things. However, again, and I’ll always repeat it, the representation is still minuscule.

I remember I wrote an article about why Frankenstein is such a good film and when you saw the comments on social media when we posted that article, everyone said: “No, no, but you’re going too far, you went three towns over.” I say Frankenstein is good for two reasons: one, because the story was written by a woman. The original Frankenstein story is written by a woman; and second, because the film, the adaptation, is made by a Latino. The beauty of Frankenstein, of the father-son relationship, especially with Guillermo del Toro’s story with his father. The sensitivity of that film, the proximity of the main character to such a beautiful femininity is what makes that film so powerful and people don’t want to see it. People see the monster. The film is good because there was a monster, no. The film is good because it’s good, because there’s diversity within the narrative, which is one of the reasons Hollywood has also become, in quotes, very boring. How many Avengers can you watch?

Eliezer: A pause and we’ll be back.

We’re back on El Hilo.

Eliezer: You were just talking about when Latino characters start to appear they start to appear only under a certain stereotype, under a certain framework, right? The problem is when that inclusion is done in a very specific way and really in the end it ends up framing you, right? It only allows you to appear in this that you were saying a moment ago, it only allows you to appear within certain schemes, right? Even when this stereotype is positive, it’s also a caricature. You can only be either the narco or the noble savage, let’s say, right? The woman can only be either the whore or the self-sacrificing wife. So, how does this also play into the configuration of the possibilities of existing that we have within a cultural industry?

Yamily: At the risk of sounding reductive, it’s the same story of the glass half full or half empty. Which is better? That’s been a discourse I’ve seen proliferate in all scenes from pure politics with what happened in Venezuela, that: “Well, but at least…” I mean, glass half full or half empty. Here it’s perfect to talk about Bad Bunny. Bad Bunny whether you like or don’t like his music, whether you like or don’t like reggaeton, whether you like or don’t like Puerto Rican music, whatever your point of view, the fact that a Latino is at halftime of the most televised event in the United States says a lot.

Archival audio, Apple Music Super Bowl Halftime Show: How good it is to be Latino, today we drink!

Yamily: Yes it had happened before, it had already happened with Shakira, Jennifer López. But again it was the same pattern. It was the hypersexualized woman that any white man wants to see shake her ass on a stage. We’re crystal clear and pardon my French.

I think what happened on Sunday was a spectacle of collective healing.

Archival audio, Apple Music Super Bowl Halftime Show: Welcome to the biggest party in the whole world…

Yamily: Bad Bunny responded to the tiny part of humanity that insists on dividing, that the only solution to disagreements is affection and love. He did it through symbolism that was not only celebratory of Latin America in general, of the community in the United States, but of the entire continent. Not only that, but he closed his show giving a master class in geography about the definition of America that goes from Patagonia to Canada.

Archival audio, Apple Music Super Bowl Halftime Show: God Bless America! Whether it’s Chile, Argentina, Uruguay…United States, Canada, my homeland Puerto Rico…

Yamily: And for all of us who watched it in real time. Whether you like or don’t like Bad Bunny’s music, whether you understand or don’t understand what he’s saying to him, the message was very clear. There are many more of us who advocate for unity and the celebration of the points where our differences unite, than the people who insist on politicizing and radicalizing those differences.

Musically speaking, he celebrated the people who came before him, he celebrated his career, he celebrated that boy he hands the Grammy to, who was a reflection of himself when he was little and at the same time the symbolism of having put a wedding in the middle with Lady Gaga, who is the symbol of whiteness, embracing, dancing. That wink to the child who sleeps on the two chairs at a wedding, was a way of telling everyone: “Latinos are something else.”

And the other thing that was very clear to me was that he celebrates one of the most important traits of the Latino community which is that, historically we have received everyone, we have opened our arms to everyone to tell them: “Come and I’ll show you how I eat, come and I’ll invite you to play dominoes, come and let’s have a coffee.” Without asking for anything in return, even when that’s naive. That has been the tradition of Latin Americans with respect to the other immigrant. We were a territory that received millions of displaced people from Europe and we always did it with open arms. Now the situation is different and he insists that we’re still the same community.

Bad Bunny is a kid who went from bagging groceries at a supermarket to becoming a phenomenon. He entered a genre that’s also very, very manipulated. It’s a genre where everyone is very packaged in the same way, whatever talent you have, you have to sound exactly the same way and you have to be the same type of product. Bad Bunny did something, he arrived and said: I don’t need to speak English.

Archival audio, Vogue: I like to speak English in private, not on camera or out there.

Yamily: I don’t need to conform to your codes to be the most streamed artist in Asia, when they’re not understanding anything I’m saying. It’s the authenticity of that kid. It’s, I think, the sign that there’s a different way of doing things. We can have many disagreements in taste, but he’s a gesture of saying: look, I’m here. Now, if you become paranoid and say: “this is also a phenomenon constructed by hegemonic power to…” I don’t know how many times they can break our hearts in one month, right? But I think that’s an example—there are ways to break with the discourse. Very personally, what do I think needs to be done to help push this wooden wheel? Consume more Latin American cinema, consume more Latin American literature, and read history—don’t ask chatGPT.

History has, unfortunately, the curse of repeating itself, because it’s the symptom of insanity. Doing things over and over again, the same way, expecting different results. That’s history’s curse. We’re repeating formats, but with many other tools. So I think there can be change, but it starts with us realizing that what happens in Hollywood doesn’t really matter that much when we have such good cinema in Latin America, when we have such good literature in Latin America. There are ways for us to turn things around and say: look, really, if I have such good mangoes at home, why am I going to buy an artificial one.

Eliezer: What you’re saying seems very accurate to me, right? And it’s something that Latin American communities, Latin American societies, tell themselves, right? Now, how do these representation patterns or their absence still affect the way Latino communities see themselves or are seen by others? Because despite what you’re saying, we’re all excited that Bad Bunny is there, we’re all excited that Pedro Pascal is there. We’re all excited about Guillermo del Toro. We’re all excited about Wagner Moura. So why is representation in the hegemonic cultural industry of the United States still important?

Yamily: Because if we’ve spent so many years without anyone paying attention to us, so many years being discriminated against, so many years being considered second-class citizens in the world order, having someone pay attention to us heals something in the collective unconscious. There’s a part of us that says: see?

Archival audio, La Clave: Why do we love Pedro Pascal? Because, regardless of the fact that he grew up in the United States, he’s really of Chilean roots and looks Chilean and shows it with pride, and I think we’re so egocentric or maybe we need that boost in our self-esteem…

Archival audio, EMBI: Despite having had success in Hollywood and being known practically throughout the world, Guillermo del Toro doesn’t forget his roots and doesn’t deny his Mexicanness.

Archival audio, Todo Noticias: The South American country’s first Oscar was celebrated like a World Cup. Very proud to be Brazilian, very proud of a film like this that deserves so much.

Yamily: I think we’ve been taught as peripheral communities—and I’m speaking from the perspective of the Arab tradition in my family, the Latino tradition in my family—we’ve been taught so much to hate ourselves, to be the echo of discrimination in our heads. That these types of representations, these moments heal very small pieces, but they do. I think Latin Americans have a lot of work to do in healing their self-hatred. If we start to heal that piece of us and—it’s being said by one of the most cynical people you’ll ever meet in your life—if we start to heal that little piece of us and say: “Look, really, no, no, no, I don’t care if you’re not recognizing me, because we’re doing other things.” But also create a market for it. I think that’s the moment when everything could change, the moment when we turn our backs and say: “Look, you know what? I have a market for myself, I have things I want to consume for myself.” In Latin American cinema of the ’80s and ’90s, that happened a lot. We had very good cinema, consumed by us, made by us, for us, and that talked about things that were happening in our society. So I think that’s what’s happening. It makes us feel good, it makes us feel euphoric because it heals a little piece that’s very broken inside.

Eliezer: Do you think that in this era, when you also have access to so much information, in all possible ways, right? If appearing or continuing to appear on a screen is still important for people who are more at the margins, at geographical margins, at racial and cultural margins—is it still important and why?

Yamily: No, I’m not going to be naive and say we should stop watching TikTok, Instagram, Netflix, and go back to… No, we’re many people battling many things at the same time. And in marginal communities, survival predominates—marginal communities don’t have the privilege of philosophizing about what should be, what they should or shouldn’t consume, because they don’t have the time. It’s important to have that representation, it’s important to see ourselves on screens because it humanizes us. Seeing a person on screen recognizes their humanity, recognizes that that person exists, and that’s the principle of human coexistence. That I recognize you as a human being. So of course it’s still important and it will continue to be important for a long time. What I think should be done is that people who have these tools to communicate start to change a little or plant that seed of: “What if we do it differently? What if we bring back other types of narratives for our communities that don’t depend so much on the person who’s on the red carpet at the Oscars?”

Eliezer: Yamily, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us.

Yamily: No, no, thank you so much. Please, this has been an honor.

Daniela Cruzat: This episode was produced by Lisa Cerda and by me, Daniela Cruzat. It was edited by Eliezer and Silvia. Desirée Yépez did the fact-checking. Sound design is by Elías González and the music is by him and Rémy Lozano.

The rest of El Hilo’s team includes Jesus Delgadillo, Samantha Proaño, Franklin Villavicencio, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, and Daniel Alarcón. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El Hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask you to join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to learn more about today’s episode, subscribe to our newsletter by going to elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it every Friday.

You can also follow us on social media. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook, and Threads. You can find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share episodes.

Thanks for listening.