Gentrificación

Ciudad de México

CDMX

Protestas

México

Turistificación

Hace algunas semanas, miles de personas salieron a protestar en contra de la gentrificación y la turistificación en Ciudad de México. La explosión de turismo y de inversiones, y el rápido crecimiento de la población extranjera en años recientes, han multiplicado la presión sobre la capital mexicana y sus habitantes, que ven cómo la especulación inmobiliaria y el desplazamiento de la población local siguen creciendo. Esta semana hablamos con el periodista Carlos Acuña, que llegó a documentar su propio desalojo, para entender cómo ha ganado un nuevo impulso la resistencia contra la gentrificación en CDMX, cuál ha sido la reacción de las autoridades y por qué los movimientos que luchan por el derecho a la vivienda no solo ponen sobre la mesa el derecho a quedarse en sus barrios, sino también una forma de habitar la ciudad.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Mariana Zúñiga -

Edición

Silvia Viñas, Eliezer Budasoff -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción en redes sociales

Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Elías González -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

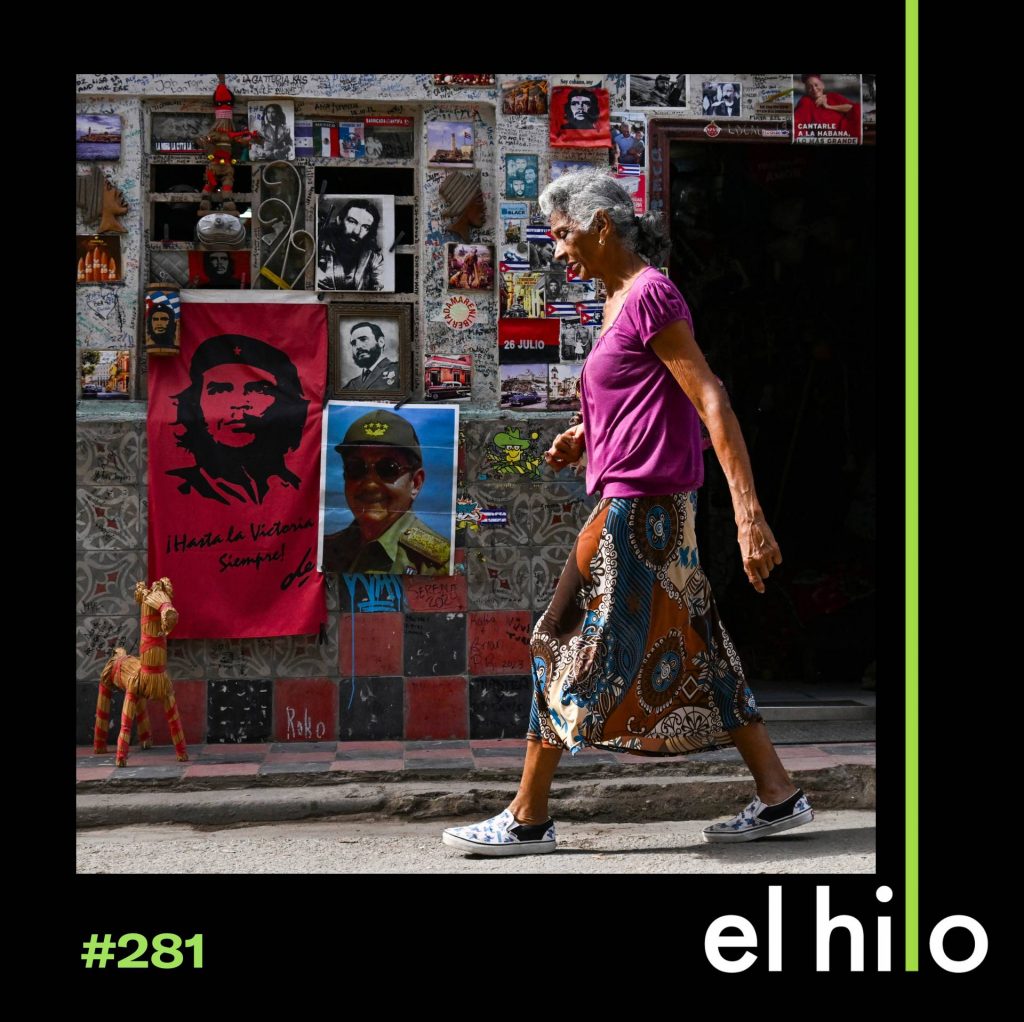

Fotografía

Getty Images / Carl de Souza

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Llevo 13 años viviendo en la Ciudad de México y en este tiempo me he tenido que mudar seis veces. Eso no me parece que sea normal.

Yo no tengo una propiedad a mi nombre, ni mi familia. Entonces nosotros siempre hemos rentado en la Ciudad de México, o en el estado.

Como indígena mazahua. Yo vengo luchando una vivienda ya más de 20 años.

Para mí la afectación ha sido en que yo considero que yo no he podido echar raíces en un lugar.

Me ha brindado mucha inestabilidad, sobre todo al saber, al no tener más bien certeza sobre cuánto más voy a tener que pagar, cuánto va a subir la renta.

Te sientes como una especie de nómada, tener que estarte moviendo de un lado para otro dependiendo de lo que se tiene que pagar, de si el arrendador ya te corrió, etcétera

Poco a poco la gentrificación ha llegado a desalojar los inmuebles y entonces fueron desalojando muchos de mis hermanos indígenas.

Mi departamento lo remataron en 300.000 pesos. Nosotros nunca nos enteramos. Hasta que de repente un día, así en la noche nos llega una persona y dice oigan: va a haber un desalojo y los van a sacar.

Silvia Viñas: Todas las personas que acaban de escuchar de una u otra manera están involucradas en la lucha por el derecho a la vivienda en la Ciudad de México.

Eliezer Budasoff: El 4 de julio participaron en la primera de tres manifestaciones que se hicieron durante ese mes en contra de la gentrificación y la turistificación de la ciudad.

Silvia: Y días después de esa primera marcha, hablaron con él.

Carlos Acuña: Bueno, yo soy Carlos Acuña, soy reportero en la Ciudad de México.

Silvia: Carlos trabaja en Fábrica de Periodismo, un medio independiente méxicano. Hablamos con él porque lleva años cubriendo el fenómeno de la gentrificación en México.

Carlos: Mira, las protestas contra la gentrificación vienen llevándose a cabo desde hace por lo menos… Pues así, de esta manera, unos diez años. Pero esta fue la más multitudinaria. Fue una protesta muy grande.

Audio archivo, protesta

Manifestantes: No se van a ir los vamos a sacar…

Carlos: Fue muy inesperado. La gente que organizaba no esperaban tanta gente. No esperaban este nivel de convocatoria. Llegaron yo creo que más de mil personas de toda la Ciudad de México, sobre todo jóvenes. Gente entre los 20 y los 30 que no están teniendo acceso a la vivienda, ya ni siquiera en renta y jóvenes que además vienen de distintas luchas identitarias, ¿no? Muchos vienen de luchas como contra el colonialismo, mucha gente que se reivindica LGBT, no binaria, etc. Y que de pronto, ven que el tema de la gentrificación los atraviesa a todos.

Audio archivo, protesta

Manifestantes: Adiós gringo, te vas de aquí…

Eliezer Budasoff: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia Viñas: Y yo soy Silvia Viñas.

Durante julio, en Ciudad de México, miles de personas salieron a protestar en contra de la gentrificación. Como respuesta, el gobierno de la ciudad presentó un paquete de políticas públicas para frenar desalojos, regular precios y garantizar el derecho a la vivienda. Eso incluía una ley para poner un límite a las rentas que debía presentarse la semana pasada, y se ha postergado hasta después de agosto. Los movimientos que luchan por el derecho a la vivienda llevan el tiempo suficiente como para saber que el problema excede las promesas o las buenas intenciones de una gestión. La especulación inmobiliaria y el desplazamiento de la población local no se han detenido en la última década, y no parece que vayan a disminuir a futuro.

Eliezer: La explosión de turismo y de inversiones, y el rápido crecimiento de la población extranjera en años recientes, han multiplicado la presión sobre la capital mexicana y sus habitantes, que exigen tomar cartas en el asunto.

Hoy, en la ciudad más poblada de norteamérica, la resistencia contra la gentrificación gana impulso con las nuevas generaciones, que ponen sobre la mesa no solo el derecho a quedarse en sus barrios, sino también una forma de habitar la ciudad.

Es 22 de agosto de 2025.

Eliezer: Carlos, ¿puedes contarnos un poco cómo surgió esa protesta y cómo es el barrio en el que la hicieron, por qué ahí y por qué ahora?

Carlos: Bueno, esto sucedió en la colonia Condesa, que es uno de los barrios, pues, donde más se ha concentrado el turismo reciente, por lo menos desde la pandemia para acá se ha llenado de lo que llaman nómadas digitales. Y bueno, siempre ha sido un barrio, un poco de clase media alta, pero también es un barrio que por lo menos desde el terremoto del 85 se había poblado de muchos habitantes de barrio, ¿no? Había muchos negocios locales, había muchas zapaterías, fruterías, etc. Entonces era un barrio muy heterogéneo en su, digamos, el tipo de población que habitaba la Condesa. Y digo en pasado porque específicamente a partir de la pandemia, la Condesa y otros barrios cercanos como la Roma, la Hipódromo, incluso la Juárez o el Centro Histórico, pues se han vertido a, digamos, la turistificación, muchos del norte global, me refiero sobre todo europeos y estadounidenses, canadienses también y pues es un choque muy loco, ¿no? Porque vemos toda una coreografía de personas trabajadoras intentando servir a estos extranjeros. Y los habitantes, pues, ya no son habitantes, son servidumbre. Y la gente que ocupa los espacios habitacionales son básicamente turistas.

Eliezer: Estas protestas recientes contra la gentrificación tuvieron bastante cobertura mediática en México, ¿no? Pero como tú nos cuentas, no es un tema nuevo. Tú vienes siguiendo este problema y escribiendo sobre el acceso a la vivienda en la capital mexicana desde hace años. Este es un tema que te ha tocado personalmente. Cuéntanos, ¿cuándo empezaste a reportearlo de forma directa y por qué?

Carlos: Mira, yo soy un afectado, pero un poco desde antes de que yo fuera afectado ya había cubierto el fenómeno en Cancún. No desde la palabra gentrificación, sino desde la palabra derecho a la ciudad.

Audio de archivo, presentador: El atractivo turístico trae consigo un alza en la migración, pero también en los precios.

Audio de archivo, experta: Los pueblos mayas son vistos como insumos, sus tierras son vistas como materia prima.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: La gentrificación está afectando a las escuelas públicas del centro de este destino turístico.

Carlos: Cuando en el 2018 yo empiezo a cubrir ya con esta palabra en la cabeza de gentrificación, es porque a mí me desalojan. Yo vivía en un edificio de los años 50 en la Alameda Central, que digamos, está en el centro Histórico, y pues poco a poco vimos como todo el barrio se iba remodelando, muchos edificios viejos se remodelaban para entregarse al turismo y al mismo tiempo comenzaba a haber muchos desalojos. En ese contexto, a nosotros en el edificio nos avisan a los vecinos que se va a vender el edificio y que teníamos, pues, un mes para pagar 80 millones de pesos.

Silvia: Eso es un poco más de cuatro millones de dólares. Carlos en esa época por alquilar en el Trevi, como se conocía a su edificio en Ciudad de México, pagaba mensualmente siete mil pesos, unos 350 dólares. O sea, les estaban pidiendo conseguir en un mes más de 11 mil veces lo que pagaban por alquilar, para poder comprar.

Carlos: Esto nos sonó muy raro porque pensamos, es demasiado dinero para el edificio y se nos está dando un mes para pagarlo. Y muchos de nosotros habíamos expresado nuestra voluntad de comprar si se abría la oportunidad. El problema es que nosotros rentamos un departamento, no un edificio completo. Y esta es una cosa muy, muy particular, porque empezamos a notar que era un patrón.

Audio de archivo, Sergio: Yo llegué como inquilino aquí a Liverpool número 9, esquina con Bruselas, en el 2005 y salí en el 2019. Nos terminaron, pues, echando fuera un desplazamiento forzado de habitantes …

Carlos: Antes de nosotros en Liverpool número nueve. Ya había pasado lo mismo.

Audio archivo, Luis: No sabemos por qué nos quieren desalojar, yo soy inquilino del Ermita. Del edificio Ermita, tengo cuatro años viviendo aquí.

Carlos: Lo mismo ocurrió en el edificio Ermita, les ofrecieron el derecho al tanto, pero en condiciones imposibles para acceder a él. Y eran pequeñas revueltas que se hacían en la ciudad, pero que quedaban muy marginales. Eran, pues, protestas que trataban de visibilizar este fenómeno, ¿no?

Y bueno, lo que sucedió en el edificio Trevi fue que, un poco por el trabajo que hicimos, tanto de organización vecinal como todos los medios que se sumaron a cubrir, se convirtió, digamos, durante unos años en el rostro de la gentrificación. Fue una lucha muy popular, pero también muy pop. Porque hicimos muchas fiestas, hicimos un discurso que no apelaba, digamos, a las marchas tradicionales, a bloqueos de calles, sino a bailes con cumbia. A tomar la calle, pero para bailar. Hacíamos pequeñitos documentales que intentábamos viralizar.

Audio archivo, documental Trevi, Carlos: De pronto aparece un Starbucks donde antes había un café histórico. Un Hotel, o decenas de cuartos en Airbnb, donde hasta hace poco vivían familias.

Carlos: Mucha obra gráfica que empezamos a difundir. Y eso permitió que los reporteros, pues, se acercaran a cubrir, ¿no? Eso lo usamos también para visibilizar muchos datos, ¿no? Yo como reportero me puse a investigar y pues nos dimos cuenta que en esos años se realizaban más o menos 3.000 desalojos al año en la Ciudad de México y 3.000 desalojos legales. No sabemos cuántos ilegales, porque el patrón es que la mayoría de los desalojos se hacen, pues, por la mala, ¿no?

Eliezer: Cuéntanos un poco más de los detalles del caso. Tú me dices que les ofrecieron de pronto en un mes comprar el edificio ¿no? Pero ¿cómo les informaron que se tenían que ir? Y bueno ¿cómo reaccionaron?

Carlos: Nos notificaron por medio de unos papeles tirados debajo de nuestras puertas en un día, en un lunes a las 11:00 de la mañana. Entonces, comenzamos a organizarnos en asamblea, y la organización vecinal fue muy atropellada y muy errática. Muchas personas no sabían que era un derecho la vivienda y que lo que estaban haciendo –ya sabíamos entonces que querían convertir ese edificio en un hotel a través de Airbnb– pues no sabían que eso pues era ilegal y lastimosamente las primeras personas que se rindieron fueron las personas con mayor necesidad económica. Ellos decidieron no pelear y quienes sí decidimos entablar una demanda, digamos, fuimos los vecinos que estábamos mínimamente academizados, que teníamos alguna licenciatura o que estaban de alguna manera con las posibilidades también de entender lo que estaba pasando y con menos miedo también, porque es una lucha muy violenta. Nosotros, pues, nos ponían de plano vigilantes en la entrada del edificio, que eran, pues, personas que se drogaban, que te agredían verbalmente cuando entrabas. En algún momento nos pusieron a trabajar como unos 50 trabajadores alrededor de los de los departamentos que resistíamos.

Audio archivo, Carlos: Oye, quería que escucharas esto y que fueras parte de este concierto que tengo desde hace seis horas casi…

Carlos: Martillando ocho horas al día para expulsarnos, digamos, de manera física, ¿no? porque hacían vibrar nuestros departamentos. Nos llegaron a cortar el agua. Hacían cosas de este tipo para hacer inhabitable ya el edificio y que nos fuéramos. Y luego en el proceso ya legal, empezaron a demandarnos a todos nosotros, ¿no? Nos demandaron por falta de pago de rentas. Cuando, pues, nosotros pagábamos ante juzgado todas las rentas desde que comenzó el conflicto, justo para que no hubiera este problema. Yo llegué a tener cuatro demandas en mi contra por no pagar renta en distintos juzgados, muchas de ellas sin notificar. Es decir, yo le decía que eran como demandas espejos, ¿no? te notifican una, pero otras tres no para que no puedas defenderte. De hecho, así se logró mi desalojo. Mi desalojo fue con todas las rentas pagadas y con un contrato de renta vigente.

Eliezer: Y cuéntame un poco del momento en que los desalojaron de forma definitiva, ¿no? El día final tú publicaste lo que estaba pasando en tiempo real.

Audio archivo, Carlos: Hola, hola a todos… acaban de hacer un desalojo en mi contra, completamente irregular. Violando debidos procesos, sin amparos de por medio…

Eliezer: ¿Nos puedes describir un poco cómo fue ese momento?

Carlos: Bueno, los desalojos fueron violentos. El más mediático fue el mío, porque llegaron un día por la mañana unos 20, 30 cargadores, que los cargadores son básicamente para policías y que muchas veces traen la orden de, pues violentar, romper tus cosas, romper las ventanas, robarse pertenencias, dinero o lo que encuentren. En mi caso, como sabían que yo era periodista, iban con la orden de no ser tan agresivos, pero pues yo ya tenía conciencia de que corría riesgo un desalojo, entonces había sacado gran parte de mis cosas. Pero decidimos usar ese desalojo como otro evento mediático. Entonces, dejamos ahí algunos sillones, alguna cama, muebles y cosas para que se ejecutara el desalojo y hacer una fiesta en la calle en cuanto eso sucediera.

Audio archivo, Carlos: Queremos festejar, queremos sacar el trauma de muchos de los que están aquí, que han perdido su casa…

Carlos: Entonces, fue bastante divertido. O sea, fue muy traumático, pero fue, digamos, siempre fue nuestra estrategia divertirnos, y un poco burlarnos de lo que estaba pasando. Pero bueno, en cuanto a mí me desalojan, comienzan a demoler mi casa, o sea, comienzan a deshacer las paredes, a deshacer los baños, así con pico y martillo para que ya no volviera, porque sabían que era un desalojo ilegal.

Eliezer: Claro, tú hablas que en medio de esto la estrategia de ustedes fue, de alguna manera, convertirlo en goce, burlarse, hacer fiestas. Ahora, en la parte agria de esto, ¿de qué manera te impacta un desalojo? Digo, como lo viviste personalmente, ¿cuál es el costo emocional y económico que viven los que son desalojados? Pero también en términos de frustración, de impotencia.

Carlos: Híjole, mira, cuando te desalojan es como quedar desnudo. Yo le decía que era como ser un náufrago. Porque te quedas sin barcos y quedas a la deriva y ves de pronto en la ciudad estos grandes rascacielos que están construyéndose y lo que sientes es que te estás enfrentando a un mal que no tiene rostro, que no tiene nombre, que son solamente la economía materializándose en expulsión, en destrucción, en tus muebles, en la calle y que estás siendo expulsado de alguna manera de la ciudad, aunque después vuelvas a incorporarte a alguna casa cerca, aunque puedas reubicarte, pues, la sensación es de completo naufragio.

Silvia: Ya volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo. El desalojo del edificio Trevi fue hace 6 años. Recordemos que en esa época el alquiler que pagaba Carlos era de siete mil pesos, que es unos 350 dólares al mes. En los últimos años, los alquileres en la ciudad han aumentado en más de un 40% por año.

Carlos: Es decir, que se han cuadruplicado o quintuplicado las rentas en estos años, sobre todo en ciertas zonas. No es un mercado inquilinario. Es un mercado especulativo. No está pensándose esas casas para que se habiten. Hay más o menos unas 200.000 casas deshabitadas en la Ciudad de México.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: El fenómeno de las viviendas abandonadas se ha vuelto cada vez más común en los últimos años.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: O sea ¿cómo puede haber tantas casas desocupadas y a la vez la vivienda estar tan cara?

Silvia: Mientras hay unas 200.000 casas deshabitadas, en la ciudad no hay una cantidad suficiente de casas dignas para la gente que no tiene dónde vivir. Es complicado hablar de una cifra exacta de personas sin hogar, pero para que se hagan una idea de la necesidad que hay, se estima que hace falta construir unas 235.000 viviendas sociales para atender la demanda.

Carlos: ¿Por qué están estas casas vacías? Bueno, porque se están usando para especular. Que estén vacías no quiere decir que no estén siendo usadas. Están siendo usadas como activos financieros en el mercado global. Porque tener una casa, te permite entrar al mercado financiero. Tener un rascacielos te permite competir en la bolsa de valores, convertir eso en activos financieros. Y muchas veces se está esperando que los precios de la zona crezcan, se dupliquen, se triplique para entonces sí, rentarla. Pero te conviene mucho más tenerlas vacías, porque si tienes a un inquilino, ese inquilino tiene derechos y no le puedes aumentar la renta 20, 30% al año, tienes que ajustarlo según la ley, aunque muchas veces se rompe de acuerdo a la inflación. Entonces, conviene mucho más tenerlas vacías para en diez años rentarla 20 veces más cara o venderla.

Carlos: Otro de los temas que estamos viendo también es todo el tema de la compra de casas. O sea, hay un estudio del ITESO que dice que solamente el 10% de la población en México puede acceder a una vivienda en compra. Los demás no tenemos acceso ya ni a la vivienda en renta, ni a la vivienda en compra, porque además los jóvenes que ahora están protestando, pues, son jóvenes que también están precarizados a nivel laboral, entonces no tienen ningún tipo de crédito hipotecario de, digamos, prestación laboral que les permita acceder a un crédito social, y bueno, hay un montón de personas jóvenes entre 20 y 30 años que siguen viviendo con sus papás porque no pueden independizarse.

Eliezer: Me gustaría que hablemos un poco de los impactos que tiene en general para la vida en la ciudad, el proceso de gentrificación y después de las responsabilidades que entran en juego, ¿no? ¿Qué implica en términos de, digamos, de una comunidad o de vecinos de un barrio, esta suba de precios y este proceso especulativo?

Carlos: Pues, desde mi punto de vista yo creo que lo que está sucediendo también es la despolitización de la ciudad. Es decir, un vecino siempre va a defender las condiciones de vida de su barrio, de su edificio, de su cuadra. ¿no? Un turista no. Un turista llega, ocupa, se sirve y se va. Un turista es un consumidor, es un usuario, pero no es un ciudadano, no es alguien que se involucre, ni en los procesos participativos de la ciudad, ni siquiera en las votaciones. Simplemente su única transacción es el dinero. Es pagar y recibir algún tipo de servicio por eso y lo demás no le importa tanto, ¿no?

Ahora lo que sucede en La Condesa, pero también en la Roma, es que la única manera en que puedes habitar ese barrio es como empleado, siendo mesero y siendo el que limpia los AIRBNBs. Y ya no hay vecinos que estén, digamos, atentos a lo que está ocurriendo a nivel de políticas públicas, a nivel de vida barrial. Entonces yo creo que es un problema de ecosistema, más no solamente de vivienda, sino de cómo el ecosistema urbano, se convierte más bien en una especie de escenificación para el turismo.

Eliezer: Claro, justo pones el dedo en algo de lo que quiero hablar contigo, porque entre los distintos factores que atraviesan este problema, el que más se ha enfocado, o se ha discutido en las redes, ¿no? Después de las protestas de julio, es la llegada de extranjeros a la ciudad. Sin empezar por el planteo absurdo de que el problema es que vengan, hay una sensación compartida y es que Ciudad de México ha vivido en la última década un proceso acelerado de inmigración tanto de América Latina, como de Estados Unidos. ¿Esto es así?

Carlos: Sí, sí hay. Digamos, le llaman los expat, ¿no? Los expatriados. Hay mucha, mucha población norteamericana llegando a la Ciudad de México. Hace poco veía que Pedro Pascal decía:

Audio archivo, Pedro Pascal: Es mi ciudad favorita, perdona a todas las otras ciudades del mundo.

Carlos: Entonces hay una revalorización de la ciudad o valorización de la ciudad. Como un imán, no solamente de turismo, sino de inversiones. Y bueno, lo vemos ahora con el Mundial, ¿no?

Audio archivo, promo: La Ciudad de México será sede del mejor fútbol del mundo, una vez más, por tercera ocasión.

Carlos: Están construyendo edificios específicamente para turistas. Entonces sí, sí es un imán de turistas y de migrantes también. Hay que hacer esa distinción.

Un migrante es alguien que llega a vivir y que llega a hacer vida con la gente y que llega a trabajar y que intenta incorporarse a la vida, a la vida social. Hay, por ejemplo, con todas las caravanas migrantes que se han hecho en los últimos años, pues una población importante de venezolanos, una población importante de haitianos, de salvadoreños que han llegado aquí a refugiarse y contra quienes no existe este señalamiento. Porque la Ciudad de México siempre ha sido un refugio de migrantes, desde siempre.

Eliezer: Claro

Carlos: Entonces, el problema no es la migración, el problema es la turistificación, porque ni siquiera es el turismo. Gran parte de la ciudad vive del turismo. El problema es que todos los ámbitos de la vida urbana se destinan al turismo y en perjuicio de los ciudadanos. Eso sí, está generando mucha tensión.

Audio de archivo, manifestantes: Fuera gringos, fuera gringos…

Carlos: Y en las protestas últimas hemos visto, pues, muchas expresiones gringo fóbicas.

Audio de archivo, manifestantes: Mi casa no es tu casa…

Carlos: Yo sí soy muy crítico con estas expresiones. Pero yo creo que hay que leerlas en el contexto también diplomático que se está viviendo en Estados Unidos. Es decir, hay una rabia contra Estados Unidos como país, porque Donald Trump está gobernando, porque allá hay redadas anti inmigrantes cada día. Porque hay un muro que nos separa. Porque hay aranceles que están imponiéndose de manera arbitraria sobre el mercado mexicano y que esto, por supuesto, se expresa en las calles hacia los individuos, hacia: lárgate, gringo, vete de aquí gringo, gringo go home, etc, que también hay que decirlo. Es decir, hay, por supuesto, muchas personas estadounidenses que vienen a querer hacer vida acá y que incluso participan en estas protestas de la gentrificación. Pero también hay expresiones de odio hacia México. Lo vimos en Mazatlán cuando se enojan cuando están tocando música sinaloense.

Lo vemos en Oaxaca. Hay muchas expresiones de maltrato de ciudadanos europeos o estadounidenses hacia expresiones culturales mexicanas que por supuesto, avivaron el fuego.

Eliezer: Me parece muy interesante esta distinción que haces también entre los, digamos, entre los turistas y los inmigrantes, ¿no? Ahora ha cambiado el perfil de la gente que llega para quedarse en los últimos años. Yo vivo acá desde 2016 y llegué con lo que parecía, en ese momento, ya una ola migratoria ¿no? pero siento que desde hace un tiempo asistimos a otra que empezó tal vez durante la pandemia y que se fue acelerando, que es de carácter distinto. ¿Estás de acuerdo con esta percepción? ¿Y por qué sería distinta a esta ola migratoria?

Carlos: Pues, yo lo que veo es que es una clase social muy alta. No son gringos nada más. O sea, no son nada más europeos y estadounidenses. Son estadounidenses de cierto carácter, con cierto nivel adquisitivo, ¿no? Los que llegan a ocupar estos espacios ¿no? Y por eso la rabia se enfoca contra ellos. Porque yo no he visto que protesten contra los haitianos. O sea, yo veo que hay sobre todo un malestar contra los europeos blancos que llegan con un sentimiento de, pues, como de doctrina Monroe ¿no? Esto es nuestro y eso molesta muchísimo, ¿no? O sea, creo que los mexicanos son muy hospitalarios. Les gusta que visiten su ciudad, les gusta presumir su cultura y sus cosas. Pero cuando llega un europeo o un gringo, sobre todo a insultar, a gritar, a adueñarse del espacio, a querer desplazar. Genera mucho malestar y genera mucha rabia. Y eso es lo que hemos estado viendo también.

Eliezer: Justo de las cuestiones que más se destacaron o que más se cubrieron de estas protestas recientes contra la gentrificación fueron algunos incidentes o las expresiones gringo fóbicas.

Audio archivo, presentadora: La manifestación comenzó pacíficamente pero derivó en actos de vandalismo, saqueo y acoso a turistas.

Audio archivo, presentadora: Han lanzado piedras, cuidado. Han lanzado, pues, algunos explosivos también.

Eliezer: Ahora, lo que yo me preguntaba es ¿a quién le conviene que esto sea visto así? Digamos, porque no sé si al movimiento es al que le conviene.

Carlos: Pues, yo creo que no es que le convenga a alguien, es que los medios de pronto se van por este tipo de expresiones, ¿no? Es mucho más escandaloso documentar que un grupo de manifestantes rompieron las ventanas de un Starbucks, o que aventaron un petardo, a documentar, pues, todo el problema de financiarización de la vivienda y meterse al tema de los bancos y meterse a cómo están subiendo las rentas. Por lo menos para la foto te sirve mucho más ver al punk enojado que está gritándole a los gringos, ¿no? Ahora bien, yo sí creo que es contraproducente. Por primera vez en la Ciudad de México se está planteando, desde la política pública, atender el problema de la gentrificación. El hecho de que de pronto la lucha por la gentrificación sea tachada de xenofóbica, echa a tierra a estos intentos, porque es muy fácil decir estos son una gente que odia, gente que está en contra de los turistas, gente que está en contra del progreso. Son xenofóbicos. Y entonces, digamos, quienes hemos estado intentando impulsar esta, pues estas políticas, de pronto somos tachados de gente que simplemente está rompiendo vidrios.

Silvia: Hacemos una última pausa y volvemos

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta.

Eliezer: ¿Qué responsabilidad crees que les cabe a las plataformas, como Airbnb, o al sector inmobiliario propio de la ciudad? Bueno, y también a la gente que viene a vivir, digamos.

Carlos: Pues, yo creo que es una responsabilidad compartida. No podemos echarle la culpa solamente a los extranjeros que vienen a vivir. De hecho, yo creo que ellos son un síntoma, no creo que sean la raíz del problema. O sea, hay una serie de políticas públicas que se han mantenido durante, pues, ya tres sexenios, más sexenios de izquierda, que han permitido que la ciudad sea un imán de inversiones globales. Cuando las inversiones globales aterrizan en el mercado local, pues se genera especulación, se genera gentrificación, se generan rascacielos que no están siendo usados. Entonces, estos complejos inmobiliarios aumentan el costo de vida y no regresan la inversión que la ciudad le permitió.

Eliezer: A mediados de julio, Clara Brugada, Jefa de Gobierno de Ciudad de México, presentó oficialmente su estrategia contra la gentrificación. ¿Nos puedes contar un poco cuáles son los puntos principales?

Carlos: Sí, ella le llama el Bando 1 y es un paquete de normas que está proponiendo. Hay algunas que ya están en la ley y que no se han cumplido. Por ejemplo, que no se aumente la renta más allá de la inflación. Establecer un índice de precios de alquiler que sea razonable. Establecer una regulación para, justo las plataformas digitales que ofrecen alquileres de corta estancia, como Airbnb, sobre todo. Hay una defensoría de derechos inquilinarios. Es decir, establecer un equipo de abogados que defienda los derechos de los inquilinos. También hacer más vivienda pública y vivienda en renta. Vivienda pública en renta. Eso es importante. Es decir, el Estado va a comenzar a hacer edificios habitacionales que se van a ofrecer en renta para grupos, pues prioritarios ¿no? Grupos como los jóvenes, las madres solteras, personas de la tercera edad, indígenas. Es un paquete de políticas que en el papel suenan muy bien.

El problema, la crítica que se ha hecho también desde los movimientos, es que no se dice cómo y cuándo se van a hacer. No establece plazos, no establece… Y también hay otras cosas que no están muy claras. Por ejemplo, todas las personas que ya fueron desalojadas, que son muchísimas. Pues no hay una política que intente reintegrar a estos vecinos a las zonas donde muchas veces todavía trabajan y tampoco se establece algo que se ha pedido desde siempre, que es una moratoria de desalojos. Y establecer qué desalojo sí es válido y que desalojo no es válido, ¿no?

Eliezer: Este panorama que se ve ahora en Ciudad de México no sólo lo han vivido ya ciudades hiper turísticas, ¿no? como Barcelona o París, sino que también está afectando a distintas ciudades de América Latina, ¿no? ¿Has visto algunos casos similares o que te hayan llamado la atención en la región, que pueden servir también para entender lo que vive México o crees que son universos completamente distintos?

Carlos: Yo creo que hay dinámicas similares y dinámicas muy específicas. No he estudiado tanto el resto de ciudades de Latinoamérica, pero digamos, cuando estábamos en el Trevi recibimos mucho apoyo de ciudades de todo el mundo. Es decir, de pronto nos contactaba gente de Los Ángeles que decían acá también estamos luchando por esto y nos hablaban de las huelgas inquilinarias que se estaban dando, sobre todo en el contexto de la pandemia. En el Trevi también recibimos de pronto apoyo de gente de España, ¿no? Gente que estaba en el barrio gótico de Barcelona y llegaban a compartir su experiencia y que nos apoyaban mucho y nos decían por favor, frenen esto, porque en el barrio Gótico de Barcelona somos los últimos dos vecinos que quedamos.

Eliezer: Wow.

Carlos: Mucha de la experiencia que está haciéndose ahora con las cooperativas de vivienda en la Ciudad de México, pues se han nutrido de experiencias de Uruguay, de Barcelona, que están un poco más avanzados en cuanto a leyes para cooperativas y que están tratando los movimientos de aprender cómo hacer otro tipo de, pues, de propiedad, que no sea la propiedad privada, sino una propiedad comunal que pueda servir también para la ciudad. Entonces, lo interesante de la gentrificación, y justo por eso es tan peligroso el discurso anti extranjero, es que es un fenómeno global, es un fenómeno que está afectando a todas las ciudades y en cada ciudad se da una resistencia. Porque no es un asunto de nacionalidades, sino de clases sociales. Y luego ya ni siquiera de clases sociales, sino de gente real contra activos financieros, ¿no?

Eliezer: Y eso me da el pie perfecto para terminar. Tú has vivido este problema desde distintos lugares y eres, de alguna manera un veterano de la lucha por el acceso a la vivienda y contra la gentrificación en Ciudad de México. ¿Para qué te parece que sirve resistir, no? más allá de lo inabarcables que puedan parecer los intereses a los que te enfrentas.

Carlos: Híjole, yo creo que ejercer tu poder como ciudadano, pues, sirve para muchas cosas. A lo mejor no vas a lograr frenar la gentrificación como tal, pero resistirte liga con la gente, ¿no? Y yo salí del Trevi con un montón de gente querida, de gente con la que se involucraron mis afectos. Y yo creo que esa comunidad que surge es justo por lo que estamos peleando, ¿no? Es decir, salir a las calles a protestar no siempre sirve para ganar una batalla, sirve para conocer gente que está en igualdad de condiciones contigo, que compartes una manera de ver el mundo que después es útil para muchas cosas, ¿no?

Yo creo que sirve para dejar de, para quitarnos un poco el estigma de víctima. No, no hay que ser víctima. Lo somos, somos afectados. Pero cuando entiendes que también eres un actor que puede incidir en la política de la ciudad, digamos, es una manera de dignificar también lo que pasó, ¿no? No te pasó porque sí, te pasó porque hay algo que está sucediendo más grande que tú. Y tú puedes contribuir a que eso se detenga, o que por lo menos que eso se hable, ¿no? Y bueno, yo siempre voy a defender el derecho a disentir, ¿no? el derecho de decir no, así no, así no se vale, ¿no? Y puedes hacerlo en cualquier momento.

Eliezer: Carlos Acuña, muchas gracias por tu tiempo.

Carlos: Muchas gracias a ti, Eliezer.

Mariana: Este episodio fue producido por mí, Mariana Zúñiga. Lo editaron Silvia y Eliezer. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido es de Elías González, con música suya y de Remy Lozano.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

I’ve been living in Mexico City for 13 years and in this time I’ve had to move six times. That doesn’t seem normal to me.

I don’t own property in my name, nor does my family. So we’ve always rented in Mexico City, or in the state.

As an indigenous Mazahua woman. I’ve been fighting for housing for more than 20 years.

For me the impact has been that I consider that I haven’t been able to put down roots in one place.

It has brought me a lot of instability, especially knowing, or rather not having certainty about how much more I’m going to have to pay, how much the rent will go up.

You feel like a kind of nomad, having to keep moving from one place to another depending on what you have to pay, whether the landlord already kicked you out, etcetera

Little by little gentrification has come to evict buildings and so they were evicting many of my indigenous brothers and sisters.

My apartment was auctioned off for 300,000 pesos. We never found out. Until suddenly one day, at night a person comes to us and says hey: there’s going to be an eviction and they’re going to kick you out.

Silvia Viñas: All the people you just heard are in one way or another involved in the fight for the right to housing in Mexico City.

Eliezer Budasoff: On July 4th they participated in the first of three demonstrations that took place during that month against gentrification and touristification of the city.

Silvia: And days after that first march, they spoke with him.

Carlos Acuña: Well, I’m Carlos Acuña, I’m a reporter in Mexico City.

Silvia: Carlos works at Fábrica de Periodismo, an independent Mexican media outlet. We spoke with him because he’s been covering the phenomenon of gentrification in Mexico for years.

Carlos: Look, the protests against gentrification have been taking place for at least… Well, like this, for about ten years. But this was the most massive. It was a very big protest.

Archive audio, protest

Protesters: They’re not going to leave, we’re going to kick them out…

Carlos: It was very unexpected. The people organizing didn’t expect so many people. They didn’t expect this level of turnout. I think more than a thousand people from all over Mexico City showed up, especially young people. People between 20 and 30 who aren’t having access to housing, not even rental anymore, and young people who also come from different identity struggles, right? Many come from struggles like against colonialism, many people who identify as LGBT, non-binary, etc. And who suddenly see that the issue of gentrification cuts through all of them.

Archive audio, protest

Protesters: Goodbye gringo, get out of here…

Eliezer Budasoff: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia Viñas: And I’m Silvia Viñas.

During July, in Mexico City, thousands of people came out to protest against gentrification. In response, the city government presented a package of public policies to stop evictions, regulate prices and guarantee the right to housing. That included a law to put a limit on rents that was supposed to be presented last week, and has been postponed until after August. The movements fighting for the right to housing have been around long enough to know that the problem exceeds the promises or good intentions of one administration. Real estate speculation and displacement of the local population haven’t stopped in the last decade, and don’t seem likely to decrease in the future.

Eliezer: The explosion of tourism and investments, and the rapid growth of the foreign population in recent years, have multiplied the pressure on the Mexican capital and its inhabitants, who demand action be taken.

Today, in the most populated city in North America, resistance against gentrification gains momentum with new generations, who put on the table not only the right to stay in their neighborhoods, but also a way of inhabiting the city.

It’s August 22, 2025.

Eliezer: Carlos, can you tell us a bit about how that protest arose and what the neighborhood where they held it is like, why there and why now?

Carlos: Well, this happened in the Condesa neighborhood, which is one of the neighborhoods, well, where tourism has been most concentrated recently, at least since the pandemic it’s been filled with what they call digital nomads. And well, it’s always been a neighborhood, a bit upper middle class, but it’s also a neighborhood that at least since the ’85 earthquake had been populated by many neighborhood residents, right? There were many local businesses, there were many shoe stores, fruit shops, etc. So it was a very heterogeneous neighborhood in its, let’s say, the type of population that inhabited Condesa. And I say in past tense because specifically since the pandemic, Condesa and other nearby neighborhoods like Roma, Hipódromo, even Juárez or the Historic Center, well they’ve turned toward, let’s say, touristification, many from the global north, I mean especially Europeans and Americans, Canadians too, and well it’s a crazy clash, right? Because we see a whole choreography of working people trying to serve these foreigners. And the inhabitants, well, are no longer inhabitants, they’re servants. And the people who occupy the residential spaces are basically tourists.

Eliezer: These recent protests against gentrification had quite a bit of media coverage in Mexico, right? But as you tell us, it’s not a new issue. You’ve been following this problem and writing about access to housing in the Mexican capital for years. This is an issue that has touched you personally. Tell us, when did you start reporting on it directly and why?

Carlos: Look, I’m someone affected, but a bit before I was affected I had already covered the phenomenon in Cancún. Not from the word gentrification, but from the phrase right to the city.

Archive audio, presenter: The tourist attraction brings with it a rise in migration, but also in prices.

Archive audio, expert: Mayan peoples are seen as inputs, their lands are seen as raw material.

Archive audio, presenter: Gentrification is affecting public schools in the center of this tourist destination.

Carlos: When in 2018 I start covering with this word in my head of gentrification, it’s because I get evicted. I lived in a building from the 1950s in Alameda Central, which let’s say, is in the Historic Center, and well little by little we saw how the whole neighborhood was being remodeled, many old buildings were remodeled to be given over to tourism and at the same time there started to be many evictions. In that context, they notified our neighbors in the building that the building is going to be sold and that we had, well, one month to pay 80 million pesos.

Silvia: That’s a little more than four million dollars. Carlos at that time to rent in the Trevi, as his building in Mexico City was known, paid monthly seven thousand pesos, about 350 dollars .In other words, they were asking them to come up with in one month more than 11 thousand times what they paid to rent, to be able to buy.

Carlos: This sounded very strange to us because we thought, it’s too much money for the building and we’re being given one month to pay it. And many of us had expressed our willingness to buy if the opportunity arose. The problem is that we rented an apartment, not a complete building. And this is a very, very particular thing, because we started to notice that it was a pattern.

Archive audio, Sergio: I arrived as a tenant here at Liverpool number 9, corner of Brussels, in 2005 and left in 2019. They ended up, well, throwing us out, a forced displacement of inhabitants …

Carlos: Before us at Liverpool number nine. The same thing had already happened.

Archive audio, Luis: We don’t know why they want to evict us, I’m a tenant of the Ermita. Of the Ermita building, I’ve been living here for four years.

Carlos: The same thing happened in the Ermita building, they offered them the right of first refusal, but under impossible conditions to access it. And they were small revolts that were happening in the city, but that remained very marginal. They were, well, protests that tried to make this phenomenon visible, right?

And well, what happened in the Trevi building was that, a bit because of the work we did, both of neighborhood organization and all the media that joined in covering, it became, let’s say, for several years the face of gentrification. It was a very popular struggle, but also very pop. Because we threw many parties, we made a discourse that didn’t appeal, let’s say, to traditional marches, to blocking streets, but to dance with cumbia. To take the street, but to dance. We made little documentaries that we tried to make viral.

Archive audio, Trevi documentary, Carlos: Suddenly a Starbucks appears where there used to be a historic café. A hotel, or dozens of rooms on Airbnb, where until recently families lived.

Carlos: A lot of graphic work that we started to spread. And that allowed reporters, well, to come cover, right? We also used that to make many facts visible, right? I as a reporter started to investigate and well we realized that in those years about 3,000 evictions per year were carried out in Mexico City and 3,000 legal evictions. We don’t know how many illegal ones, because the pattern is that most evictions are done, well, the hard way, right?

Eliezer: Tell us a bit more about the details of the case. You tell me that suddenly they offered you to buy the building in one month, right? But how did they inform you that you had to leave? And well, how did you react?

Carlos: They notified us by means of some papers thrown under our doors one day, on a Monday at 11:00 in the morning. So, we started to organize in assembly, and the neighborhood organization was very rushed and very erratic. Many people didn’t know that housing was a right and that what they were doing –we already knew then that they wanted to convert that building into a hotel through Airbnb– well they didn’t know that that was illegal and unfortunately the first people who gave up were the people with the greatest economic need. They decided not to fight and those of us who did decide to file a lawsuit, let’s say, were the neighbors who were minimally academized, who had some undergraduate degree or who were somehow with the possibilities also of understanding what was happening and with less fear too, because it’s a very violent struggle. We, well, they put plain guards at the entrance of the building, who were, well, people who did drugs, who verbally attacked you when you entered. At some point they put about 50 workers around the apartments that we were resisting to work.

Archive audio, Carlos: Hey, I wanted you to hear this and be part of this concert I’ve had for almost six hours…

Carlos: Hammering eight hours a day to expel us, let’s say, physically, right? because they made our apartments vibrate. They even cut off our water. They did things like this to make the building uninhabitable and make us leave. And then in the legal process, they started to sue all of us, right? They sued us for non-payment of rent. When, well, we paid all the rents to the court since the conflict began, precisely so there wouldn’t be this problem. I ended up having four lawsuits against me for not paying rent in different courts, many of them without notice. That is, I said they were like mirror lawsuits, right? they notify you of one, but not the other three so you can’t defend yourself. In fact, that’s how my eviction was achieved. My eviction was with all rents paid and with a valid rental contract.

Eliezer: And tell me a bit about the moment when they definitively evicted you, right? The final day you published what was happening in real time.

Archive audio, Carlos: Hello, hello everyone… they just carried out an eviction against me, completely irregular. Violating due process, without any injunctions…

Eliezer: Can you describe to us a bit what that moment was like?

Carlos: Well, the evictions were violent. The most mediatic was mine, because about 20, 30 loaders arrived one morning, and loaders are basically for police and they often come with orders to, well, be violent, break your things, break windows, steal belongings, money or whatever they find. In my case, since they knew I was a journalist, they came with orders not to be so aggressive, but well I was already aware that I was at risk of eviction, so I had taken out most of my things. But we decided to use that eviction as another media event. So, we left some armchairs there, a bed, furniture and things for the eviction to be executed and threw a party in the street as soon as that happened.

Archive audio, Carlos: We want to celebrate, we want to get the trauma out of many of those who are here, who have lost their home…

Carlos: So, it was quite fun. I mean, it was very traumatic, but it was, let’s say, it was always our strategy to have fun, and kind of make fun of what was happening. But well, as soon as they evict me, they start demolishing my house, I mean, they start tearing down the walls, tearing down the bathrooms, like with a pickaxe and hammer so I wouldn’t come back, because they knew it was an illegal eviction.

Eliezer: Right, you talk about how in the middle of this your strategy was, somehow, to turn it into enjoyment, to make fun, throw parties. Now, on the bitter side of this, how does an eviction impact you? I mean, how did you experience it personally, what is the emotional and economic cost experienced by those who are evicted? But also in terms of frustration, of powerlessness.

Carlos: Jeez, look, when they evict you it’s like being left naked. I used to say it was like being a castaway. Because you’re left without ships and you’re left adrift and you suddenly see in the city these big skyscrapers that are being built and what you feel is that you’re facing an evil that has no face, that has no name, that is just the economy materializing into expulsion, into destruction, into your furniture, in the street and that you’re being expelled somehow from the city, even if you later reintegrate into some house nearby, even if you can relocate, well, the sensation is of complete shipwreck.

Silvia: We’ll be right back.

Silvia: We’re back on El hilo. The eviction from the Trevi building was 6 years ago. Let’s remember that at that time the rent Carlos paid was seven thousand pesos, which is about 350 dollars a month. In recent years, rents in the city have increased by more than 40% per year.

Carlos: That is, rents have quadrupled or quintupled in these years, especially in certain areas. It’s not a rental market. It’s a speculative market. Those houses aren’t being thought of to be inhabited. There are roughly 200,000 uninhabited houses in Mexico City.

Archive audio, host: The phenomenon of abandoned housing has become increasingly common in recent years.

Archive audio, host: I mean, how can there be so many unoccupied houses and at the same time housing be so expensive?

Silvia: While there are about 200,000 uninhabited houses, in the city there isn’t a sufficient quantity of decent houses for people who have nowhere to live. It’s complicated to talk about an exact figure of homeless people, but to give you an idea of the need that exists, it’s estimated that about 235,000 social housing units need to be built to meet demand.

Carlos: Why are these houses empty? Well, because they’re being used to speculate. That they’re empty doesn’t mean they’re not being used. They’re being used as financial assets in the global market. Because having a house allows you to enter the financial market. Having a skyscraper allows you to compete on the stock exchange, convert that into financial assets. And many times they’re waiting for the prices in the area to grow, double, triple to then yes, rent it out. But it’s much more convenient for you to have them empty, because if you have a tenant, that tenant has rights and you can’t raise the rent 20, 30% per year, you have to adjust it according to the law, although many times it’s broken according to inflation. So, it’s much more convenient to have them empty to in ten years rent it out 20 times more expensive or sell it.

Carlos: Another issue we’re also seeing is the whole issue of buying houses. I mean, there’s a study by ITESO that says only 10% of the population in Mexico can access housing for purchase. The rest of us no longer have access to rental housing, nor to housing for purchase, because also the young people who are now protesting, well, are young people who are also precarized at the labor level, so they don’t have any type of mortgage credit or, let’s say, labor benefit that allows them to access social credit, and well, there are a lot of young people between 20 and 30 years old who continue living with their parents because they can’t become independent.

Eliezer: I’d like us to talk a bit about the impacts it has in general for life in the city, the gentrification process and then about the responsibilities that come into play, right? What does it imply in terms of, let’s say, a community or neighbors in a neighborhood, this price increase and this speculative process?

Carlos: Well, from my point of view I think what’s also happening is the depoliticization of the city. That is, a neighbor will always defend the living conditions of their neighborhood, their building, their block, right? A tourist won’t. A tourist arrives, occupies, serves themselves and leaves. A tourist is a consumer, is a user, but is not a citizen, is not someone who gets involved, neither in the participatory processes of the city, nor even in voting. Simply, their only transaction is money. It’s paying and receiving some type of service for that and the rest doesn’t matter much to them, right?

Now what happens in Condesa, but also in Roma, is that the only way you can inhabit that neighborhood is as an employee, being a waiter and being the one who cleans the Airbnbs. And there are no longer neighbors who are, let’s say, attentive to what’s happening at the level of public policies, at the level of neighborhood life. So I think it’s an ecosystem problem, not just housing, but how the urban ecosystem becomes more like a kind of staging for tourism.

Eliezer: Right, you’re putting your finger on something I want to talk with you about, because among the different factors that cross through this problem, the one that has been most focused on, or discussed on social media, right? After the July protests, is the arrival of foreigners to the city. Without starting with the absurd idea that the problem is that they come, there’s a shared feeling and it’s that Mexico City has experienced in the last decade an accelerated process of immigration both from Latin America and from the United States. Is this so?

Carlos: Yes, yes there is. Let’s say, they call them expats, right? The expatriates. There’s a lot, a lot of North American population arriving in Mexico City. I recently saw that Pedro Pascal said:

Archive audio, Pedro Pascal: It’s my favorite city, sorry to all the other cities in the world.

Carlos: So there’s a revaluation of the city or valuation of the city. Like a magnet, not only for tourism, but for investments. And well, we see it now with the World Cup, right?

Archive audio, promo: Mexico City will host the best football in the world, once again, for the third time.

Carlos: They’re building buildings specifically for tourists. So yes, yes it’s a magnet for tourists and migrants too. We have to make that distinction.

A migrant is someone who comes to live and who comes to make life with people and who comes to work and who tries to incorporate into life, into social life. There is, for example, with all the migrant caravans that have been happening in recent years, well an important population of Venezuelans, an important population of Haitians, of Salvadorans who have come here to take refuge and against whom this pointing doesn’t exist. Because Mexico City has always been a refuge for migrants, always.

Eliezer: Right

Carlos: So, the problem isn’t migration, the problem is touristification, because it’s not even tourism. A large part of the city lives from tourism. The problem is that all areas of urban life are destined for tourism and to the detriment of citizens. That yes, is generating a lot of tension.

Archive audio, protesters: Out gringos, out gringos…

Carlos: And in the recent protests we’ve seen, well, many gringo-phobic expressions.

Archive audio, protesters: My house is not your house…

Carlos: I am very critical of these expressions. But I think they have to be read in the diplomatic context that’s also being experienced in the United States. That is, there’s rage against the United States as a country, because Donald Trump is governing, because there are anti-immigrant raids there every day. Because there’s a wall that separates us. Because there are tariffs being imposed arbitrarily on the Mexican market and that this, of course, is expressed in the streets toward individuals, toward: get lost, gringo, get out of here gringo, gringo go home, etc, which also has to be said. That is, there are, of course, many American people who come wanting to make life here and who even participate in these gentrification protests. But there are also expressions of hatred toward Mexico. We saw it in Mazatlán when they get angry when they’re playing Sinaloan music.

We see it in Oaxaca. There are many expressions of mistreatment by European or American citizens toward Mexican cultural expressions that of course, fanned the flames.

Eliezer: I find this distinction you make between, let’s say, between tourists and immigrants very interesting, right? Now the profile of people who come to stay has changed in recent years. I’ve lived here since 2016 and arrived with what seemed, at that moment, already a migratory wave, right? but I feel that for some time we’ve been witnessing another one that maybe started during the pandemic and has been accelerating, which is of a different character. Do you agree with this perception? And why would it be different from this migratory wave?

Carlos: Well, what I see is that it’s a very high social class. They’re not just gringos. I mean, they’re not just Europeans and Americans. They’re Americans of a certain character, with a certain purchasing power, right? Those who come to occupy these spaces, right? And that’s why the rage is focused against them. Because I haven’t seen them protest against Haitians. I mean, I see that there’s especially discomfort against white Europeans who arrive with a feeling of, well, like Monroe Doctrine, right? This is ours and that bothers a lot, right? I mean, I think Mexicans are very hospitable. They like people to visit their city, they like to show off their culture and their things. But when a European or a gringo arrives, especially to insult, to shout, to take over the space, to want to displace. It generates a lot of discomfort and generates a lot of rage. And that’s what we’ve been seeing too.

Eliezer: Precisely one of the issues that stood out most or was most covered about these recent protests against gentrification were some incidents or gringo-phobic expressions.

Archive audio, presenter: The demonstration began peacefully but resulted in acts of vandalism, looting and harassment of tourists.

Archive audio, presenter: They have thrown stones, be careful. They have thrown, well, some explosives too.

Eliezer: Now, what I wondered is who does it benefit for this to be seen this way? I mean, because I don’t know if it benefits the movement.

Carlos: Well, I think it’s not that it benefits someone, it’s that the media suddenly go for this type of expression, right? It’s much more scandalous to document that a group of protesters broke the windows of a Starbucks, or that they threw a firecracker, than to document, well, the whole problem of financialization of housing and get into the issue of banks and get into how rents are going up. At least for the photo it serves you much better to see the angry punk who’s yelling at the gringos, right? Now then, I do think it’s counterproductive. For the first time in Mexico City it’s being proposed, from public policy, to address the problem of gentrification. The fact that suddenly the struggle against gentrification is labeled as xenophobic, undermines these attempts, because it’s very easy to say these are people who hate, people who are against tourists, people who are against progress. They’re xenophobic. And so, let’s say, those of us who have been trying to promote these, well these policies, suddenly we’re labeled as people who are simply breaking glass.

Silvia: We take one last break and we’ll be back

Silvia: We’re back.

Eliezer: What responsibility do you think platforms like Airbnb have, or the city’s own real estate sector? Well, and also the people who come to live, let’s say.

Carlos: Well, I think it’s a shared responsibility. We can’t just blame the foreigners who come to live. In fact, I think they’re a symptom, I don’t think they’re the root of the problem. I mean, there’s a series of public policies that have been maintained for, well, already three six-year terms, more left-wing six-year terms, that have allowed the city to be a magnet for global investments. When global investments land in the local market, well speculation is generated, gentrification is generated, skyscrapers that aren’t being used are generated. So, these real estate complexes increase the cost of living and don’t return the investment that the city allowed them.

Eliezer: In mid-July, Clara Brugada, Head of Government of Mexico City, officially presented her strategy against gentrification. Can you tell us a bit about what the main points are?

Carlos: Yes, she calls it Bando 1 and it’s a package of norms she’s proposing. There are some that are already in the law and haven’t been complied with. For example, that rent will not be increased beyond inflation. Establish a rental price index that’s reasonable. Establish regulation for, precisely, the digital platforms that offer short-stay rentals, like Airbnb, especially. There’s a tenants’ rights ombudsman. That is, establish a team of lawyers who defend tenants’ rights. Also make more public housing and rental housing. Public rental housing. That’s important. That is, the State is going to start making residential buildings that are going to be offered for rent to priority groups, right? Groups like young people, single mothers, elderly people, indigenous people. It’s a package of policies that on paper sound very good.

The problem, the criticism that has also been made from the movements, is that it doesn’t say how and when they’re going to be done. It doesn’t establish deadlines, it doesn’t establish… And there are also other things that aren’t very clear. For example, all the people who were already evicted, who are very many. Well there’s no policy that tries to reintegrate these neighbors into the areas where they often still work and also nothing is established that has been asked for always, which is a moratorium on evictions. And establish which eviction is valid and which eviction is not valid, right?

Eliezer: This panorama that’s seen now in Mexico City has not only been experienced by hyper-touristic cities, right? like Barcelona or Paris, but it is also affecting different cities in Latin America, right? Have you seen some similar cases or ones that have caught your attention in the region, that can also serve to understand what Mexico is experiencing or do you think they’re completely different universes?

Carlos: I think there are similar dynamics and very specific dynamics. I haven’t studied the rest of Latin American cities as much, but let’s say, when we were in Trevi we received a lot of support from cities around the world. That is, suddenly people from Los Angeles contacted us saying we’re also fighting for this and they told us about the rent strikes that were happening, especially in the context of the pandemic. At the Trevi we also suddenly received support from people from Spain, right? People who were in the Gothic quarter of Barcelona and came to share their experience and who supported us a lot and told us please, stop this, because in the Gothic quarter of Barcelona were the last two neighbors left.

Eliezer: Wow.

Carlos: Much of the experience being done now with housing cooperatives in Mexico City, well they’ve been nourished by experiences from Uruguay, from Barcelona, that are a bit more advanced in terms of laws for cooperatives and that the movements are trying to learn how to make another type of, well, property, that isn’t private property, but communal property that can also serve the city. So, what’s interesting about gentrification, and precisely why the anti-foreign discourse is so dangerous, is that it’s a global phenomenon, it’s a phenomenon that’s affecting all cities and in each city resistance happens. Because it’s not a matter of nationalities, but of social classes. And then not even of social classes, but of real people against financial assets, right?

Eliezer: And that gives me the perfect lead-in to finish. You’ve experienced this problem from different places and you’re, somehow, a veteran of the struggle for access to housing and against gentrification in Mexico City. What do you think resisting is good for, right? beyond how overwhelming the interests you’re facing might seem.

Carlos: Jeez, I think exercising your power as a citizen, well, serves for many things. Maybe you’re not going to manage to stop gentrification as such, but resisting connects you with people, right? And I came out of the Trevi with a bunch of dear people, people with whom my affections got involved. And I think that community that emerges is precisely what we’re fighting for, right? That is, going out to the streets to protest doesn’t always serve to win a battle, it serves to meet people who are in equal conditions with you, who share a way of seeing the world that later is useful for many things, right?

I think it serves to stop, to remove a bit the stigma of victimisation from ourselves. No, we don’t have to be victims. We are, we’re affected. But when you understand that you’re also an actor who can influence the politics of the city, let’s say, it’s a way of also dignifying what happened, right? It didn’t happen to you just because, it happened to you because there’s something happening bigger than you. And you can contribute to that stopping, or at least to that being talked about, right? And well, I’ll always defend the right to dissent, right? the right to say no, not like that, that’s not fair, right? And you can do it at any moment.

Eliezer: Carlos Acuña, thank you very much for your time.

Carlos: Thank you very much, Eliezer.

Mariana: This episode was produced by me, Mariana Zúñiga. It was edited by Silvia and Eliezer. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design is by Elías González, with his music and Remy Lozano’s.

The rest of El hilo team includes Daniela Cruzat, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask you to join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to delve deeper into today’s episode, subscribe to our newsletter by going to elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it every Friday.

You can also follow us on our social networks. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook and Threads. Find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share episodes.

Thanks for listening.