Libertad de prensa

Periodismo

Prensa

El Faro

El Salvador

Nayib Bukele

Nicaragua

Daniel Ortega

Guatemala

Exilio

Este episodio fue producido gracias al apoyo de Reporteros Sin Fronteras, Civil Rights Defenders, Instituto sobre Raza, Igualdad y Derechos Humanos, y Free Press Unlimited.

En los últimos meses, más de 40 periodistas se han exiliado de El Salvador a causa de la persecución del gobierno de Nayib Bukele. El éxodo salvadoreño es el capítulo más reciente del asedio general que vive la prensa en Centroamérica, y que tiene como modelo más extremo a Nicaragua. El régimen de Ortega ya ha forzado a salir a más de 280 comunicadores, y ha convertido gran parte del país en un desierto informativo. Este episodio fue grabado durante tres días en Costa Rica, en el momento en que un grupo de reporteros de El Faro se estaban convirtiendo en exiliados; a través de esa historia y la experiencia de jóvenes nicaragüenses que salieron de su tierra hace años, tratamos de entender qué significa, para sociedades que están perdiendo sus derechos, el destierro de las personas que están dispuestas a denunciarlo.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Eliezer Budasoff -

Edición

Silvia Viñas -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción en redes

Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Elías González -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

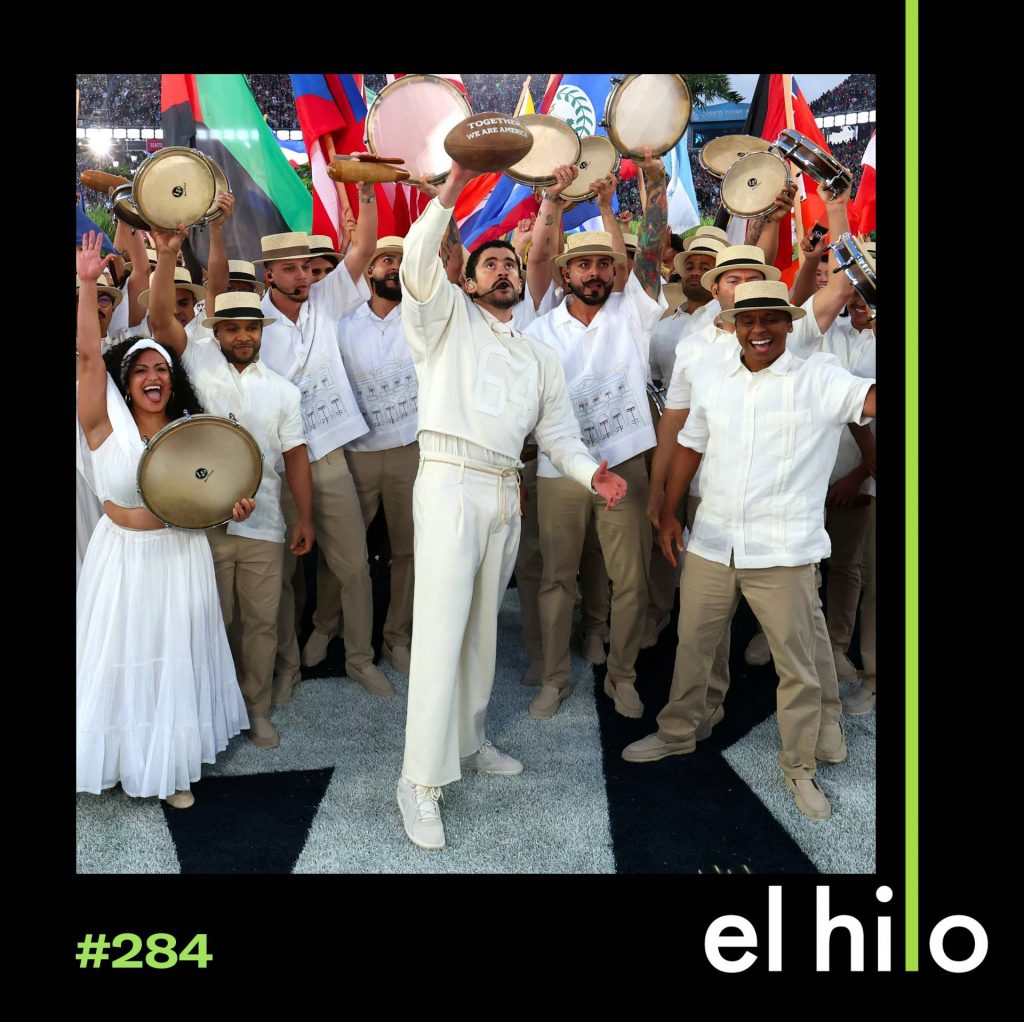

Fotografía

Carlos Barrera / El Faro

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Este episodio fue producido gracias al apoyo de Reporteros Sin Fronteras, Civil Rights Defenders, Instituto sobre Raza, Igualdad y Derechos Humanos y Free Press Unlimited.

Eliezer Budasoff: En junio de este año, a lo largo de un fin de semana, pude ver en directo cómo un grupo de colegas y amigos salvadoreños se convertían en exiliados. Todo esto pasó en un lapso de tres días, en medio de un encuentro de periodismo en Costa Rica, y empezó con una entrevista que no quería hacer.

Eliezer Budasoff: Lo primero que les voy a pedir es si se pueden presentar.

Óscar Martínez: Yo soy Óscar Martínez, periodista salvadoreño y jefe de redacción de ElFaro.net.

Carlos Martínez: Yo soy Carlos Martínez, reportero del periódico ElFaro.net.

Silvia Viñas: Es posible que hayan escuchado a Carlos y a Óscar en otros episodios de El hilo. En los últimos años hablamos varias veces con ellos y otros periodistas de El Faro para que nos ayudaran a entender noticias clave de El Salvador: el régimen de excepción, el bitcoin, la desarticulación de las pandillas….

Eliezer: En el momento de esta entrevista, Carlos y Óscar llevan más de un mes fuera de su país, y tenían la misma cantidad de tiempo sin verse. Se volvieron a encontrar en este hotel, donde estamos ahora sentados, en el patio, con la grabadora encima de la mesa. Es un viernes, 6 de junio, a la hora de la siesta.

Eliezer Budasoff: ¿Me podés contar dónde estamos en este momento y por qué?

Oscar: Estamos ahorita en San José, Costa Rica, en medio del Foro Centroamericano de Periodismo, que ha sido como el lugar donde nos hemos logrado juntar con el equipo de nuevo. Pero varias personas que salimos antes del 1 de mayo de este 2025, porque íbamos a publicar las entrevistas a dos líderes pandilleros prófugos y sabíamos que eso iba a tener repercusión.

Silvia: En esos videos que publicaron el 1° de mayo, los líderes pandilleros contaban detalles reveladores sobre los acuerdos que habían mantenido con el presidente Nayib Bukele desde que era alcalde. Decían cosas dolorosas para los salvadoreños, cosas difíciles de tapar, incluso para la maquinaria de comunicación del gobierno. Bukele se puso furioso. Hicimos un episodio sobre eso.

Carlos: Creo que hablo a nombre de los dos cuando digo que salimos del país subestimando las consecuencias de esta publicación. Es decir, los dos salimos con maletas para semana y media.

Eliezer: Enseguida se dieron cuenta de que habían hecho mal el cálculo. Los videos estallaron y tomaron por asalto las redes, el territorio donde Bukele ha construido su reinado.

Oscar: Los primeros días que estábamos afuera nos enteramos por dos fuentes distintas, con conocimiento interno de los procesos, de que en la Fiscalía se habían preparado siete órdenes de captura, al menos contra miembros de El Faro. Justo después de la publicación.

Silvia: Después, las cosas solo se pusieron peores en El Salvador. Durante todo mayo, Bukele persiguió, reprimió, encarceló. Y Carlos y Óscar tuvieron que ir aplazando la vuelta. Pero en este punto, cuando Eliezer se sienta a hablar con ellos, han pasado más de 30 días desde que salieron del país, y están decididos a volver. Ya tienen pasaje de avión a San Salvador para el día siguiente, el sábado 7 de junio, igual que varios compañeros más del periódico. Creemos que hay un riesgo bastante grande de que los detengan cuando lleguen al aeropuerto, o de que vayan a buscarlos a sus casas unos días después. Por eso Eliezer los está entrevistando.

Eliezer: No es la primera vez que salen del país cuando van a publicar una bomba y vuelven cuando pasa la tormenta. Pero esta vez la situación es distinta. Dos semanas atrás, la policía de Bukele había detenido a Ruth López, una de las principales defensoras de derechos humanos de El Salvador. La fueron a buscar a su casa a medianoche, la tuvieron incomunicada por 15 días y la dejaron en prisión. A nadie le parece buen momento para que vuelvan. El problema es que ellos saben que el gobierno los quiere afuera del país, y no les basta con una amenaza. Si hay una orden de detención, como les dijeron sus fuentes, quieren verla.

Óscar: Nosotros formalmente, a través de un apoderado legal, solicitamos a la Fiscalía saber si había órdenes de detención o delitos o denuncias de delitos contra siete miembros del periódico, los siete que firmamos la pieza polémica. La fiscalía ya pasó el plazo de los 15 días hábiles para contestar y no ha contestado. Hemos hecho lo que la ley dice que se tiene que hacer en estos casos. Y al no haber respuesta, ni haber más indicios, porque está completamente cerrada la información, hemos empezado a discutir y hemos tomado esta decisión. No hay información, no tenemos una orden de captura que podamos ver. Tenemos los testimonios de quienes la vieron. Y con esa información aún no nos queremos ir.

Silvia: “Aún no nos queremos ir”, en este caso, significa que todavía no están dispuestos a exiliarse. No con esas pruebas. La noche anterior, ellos y un grupo de periodistas de El Faro se habían reunido para hablar una última vez con los abogados que los estaban apoyando desde El Salvador, y contarles el plan de volver el sábado.

Eliezer: La reunión fue todo lo alentadora que podía ser con la información objetiva que manejaban. Es decir: fue deprimente. Yo estaba ahí sentado con ellos, en un bar medio vacío, con la cabeza inclinada sobre la mesa para escuchar lo que decían los abogados por el altavoz de un teléfono. No tenían novedades para contarles. Habían hecho lo posible para saber si los acusaban de algo o si tenían órdenes de captura, pero la Fiscalía seguía sin responder. Después de varias consultas técnicas, Carlos hizo la pregunta del millón:

Carlos: En tú opinión, en los días próximos, si volvemos el sábado, ¿seremos objeto de detención o entra dentro de la lógica que has podido observar en los casos que has seguido una detención al cabo de una semana, o al cabo de un mes y esto? Nos gustaría un montón escuchar tu criterio sobre eso.

Eliezer: El abogado dijo esto, casi textualmente: que el problema que había con esa pregunta era que tratar de predecir lo que hacían las autoridades era tratar de predecir lo que decía el presidente. Y que tratar de predecir lo que pensaba o hacía el presidente, era como tratar de predecir a un niño de 11 o 12 años. O sea, una tarea bien complicada.

Silvia: Su recomendación, después de darles ejemplos específicos sobre la falta de lógica con la que opera el gobierno, era que no metieran las manos en el fuego. Que con el nivel de capricho, emoción y ausencia de racionalidad con el que el gobierno toma decisiones, no había nada que impidiera que los detuvieran.

Eliezer: Lamentablemente, eso no alcanzaba para hacerles cambiar de idea, porque seguía siendo una especulación. Por eso estábamos en el patio de un hotel en Costa Rica, a la hora de la siesta, grabando una entrevista que yo no quería hacer. O sea: yo estaba entrevistando a mis amigos por si los metían a la cárcel cuando volvieran a su país, solo por hacer bien su trabajo. Como mucha gente más, yo no quería que volvieran. Traté de entender por qué tomaban esa decisión, pero en el fondo, lo que yo quería saber es por qué era tan difícil convencerlos de que se exiliaran. Esa era, para mí, la pregunta del millón. Por qué, para un periodista que ha investigado y documentado la transformación de su país en un régimen autoritario, es tan difícil exiliarse cuando esa realidad lo alcanza.

Silvia: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: Y yo soy Eliezer Budasoff.

La prensa independiente vive un asedio generalizado en Centroamérica. Esto no es nuevo, ni empezó con Bukele. Es un proceso que arrancó en Nicaragua, y viene acelerándose a partir de 2018, después del gran estallido social en ese país, cuando Daniel Ortega desató una persecución abierta contra cualquiera que se animara a hablar de su gobierno. Y después, contra cualquiera que quisiera contar algo sobre la realidad. En los últimos seis años, más de 280 periodistas nicaragüenses han sido forzados al exilio, y el régimen ha cerrado o confiscado más de 50 medios. La mayor parte del territorio ya entra en la categoría de “desierto de información”. Diez de los 15 departamentos no tienen periodistas. Ni uno solo. Ni una página de Facebook con anuncios locales.

Silvia: Las acciones de Ortega, que lleva casi dos décadas consecutivas en el poder, han trazado una hoja de ruta para proyectos autócratas como el de Nayib Bukele en El Salvador, o para grupos de poder corruptos como los de Guatemala, que persiguen el mismo silencio, el mismo bloqueo informativo. Los periodistas críticos de Centroamérica se han vuelto como los canarios de las minas de carbón que anticipan cómo están asfixiando a sus países. El costo que pagan por contar lo que pasa y desmontar las narrativas del poder es altísimo, pero no solo para ellos.

Hoy: qué significa, para una sociedad que está perdiendo sus derechos, el exilio de la gente que está dispuesta a documentarlo y denunciarlo.

Es 3 de octubre de 2025.

Eliezer: Hacemos una pausa breve y volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Eliezer: La tarde del viernes 6 de junio, cuando entrevisté a Carlos y a Óscar, ellos estaban a pocas horas de convertirse en exiliados, pero todavía no lo sabían. Tenían claro que eso les tocaba pronto, pero creían que les quedaba una chance más de entrar al país. Y que iban a poder salir después.

Les pregunté directamente por qué volvían. Eso tenía más de una respuesta, pero la primera atravesaba todo lo demás.

Óscar: Creo que en El Salvador todavía quedan varios periodistas ─como se vio en la audiencia de Ruth López cuando se llenó de periodistas cubriendo esa audiencia─, haciendo su trabajo. Yo quiero ser uno de ellos ahorita, yo quiero estar haciendo mi trabajo en El Salvador y prefiero, entiendo el riesgo, no soy ingenuo. Llevo años haciendo esto, pero prefiero jugarme ese riesgo por la virtud de poder ejecutar una cobertura de una dictadura que está aplastando gente desde dentro del país. Un día, dos días, una semana, un mes, el tiempo que sea posible.

Carlos: Nos tocó ser periodistas en un momento en el que El Salvador se precipita a una dictadura y me parece a mí que los periodistas somos, en muy resumidas cuentas, vigilantes, vigilantes del poder, vigilantes del quehacer de la sociedad. Y creo que esa es una responsabilidad que se asume sobre todo en circunstancias como estas. De manera que creo que regresar al país a intentar hacer periodismo, como decía Oscar, un día, dos días, tres días, es jugarse y usar los centímetros de libertad que nos quedan hasta que la dictadura se cierre completamente.

Silvia: En esa última frase se alojaba toda la tensión de ese momento: en la creencia de que todavía les quedaba un pequeño margen para volver, hacer su trabajo y despedirse del país. Carlos lo medía en centímetros, Óscar en días.

Eliezer: Para mí no les quedaba margen de nada. Era una conclusión a la que uno podía llegar de forma convincente viendo lo que ellos mismos publicaban. Pero claro, yo no tenía que elegir entre la posibilidad de que me metieran a la cárcel o renunciar a mi vida tal como la conocía.

Carlos: Creo que no solo nos jugamos los últimos centímetros para ejercer el oficio, sino los últimos centímetros, probablemente para despedirnos de todo aquello que es nuestro, de nuestra casa, de nuestra vida, de la cercanía con los nuestros y con nuestro país. Y creo que eso también vale la pena, pues…

Eliezer: ¿Qué les ha dicho la gente respecto de la vuelta? ¿Qué les han dicho sus familiares? ¿Qué les han dicho sus colegas?

Óscar: Yo no conozco a nadie que me haya dicho que volvamos. No sé si vos. Todo el mundo nos ha dicho que no. Lo que pasa es que luego, cuando les elaboras la respuesta y les decís: ¿Vos te irías con esta evidencia? ¿Dejarías tu país, dejarías la esencia de tu oficio, dejarías el lugar donde ejecutas tu credo? Y entonces la respuesta les es más difícil. Vos si crees que hay una oportunidad, ─les he preguntado yo─, de volver, como yo creo que la hay, ¿no la tomarías? Y en ese momento ya la respuesta no es tan directa.

Carlos: La mierda, Buda, es que normalmente el exilio, o la cárcel bajo una dictadura, había sido para mi generación una cosa que le ocurrió a la generación de mis padres, en la guerra civil, bajo las dictaduras militares. Y luego siempre una cosa que les pasaba a otros, a los que veíamos desde lejos y acuerpábamos y sobre los que escribíamos, a las personas que habitaban satrapías como la nicaragüense o la venezolana, pues. Asumirlo para uno es bien difícil. Estar en medio de esta decisión es asumir con radicalidad una condición que siempre te imaginaste en otros, y en otros tiempos. De manera que asumirte un exiliado tiene también una serie de dificultades en tanto a tu oficio, al compromiso y a la manera en la que le hallás sentido a ejercer tu trabajo y, además, a todo lo que has entendido como vida. ¿Vos dejarías de hacerlo? Es eso. ¿Vos dejarías de hacerlo? Si crees que tenés todavía, como dice Oscar, unos metros para habitar todo lo que acabo de decir. Entonces no es así nomás asumir eso y no es así nomás claudicar o decidir abandonar eso de la noche a la mañana, pues. Entonces, si creo que hay unos centímetros, los quiero tener, los quiero vivir.

Eliezer: Les hice dos preguntas más, pero era difícil seguir después de eso. Yo no tenía una respuesta. Eran casi las 4 de la tarde del viernes y el futuro estaba demasiado cerca para poder pensar en otra cosa. En menos de 24 horas ellos tenían pasaje para El Salvador, en un par de horas era la clausura del Foro Centroamericano de Periodismo, y ahora mismo tenían que responder mensajes y llamados de gente cercana que se iba enterando de que iban a volver. Todavía no habían dicho nada públicamente, pero la noticia ya circulaba en algunos grupos cerrados.

Esa noche, cuando presentó la última actividad del foro, el periodista costarricense Álvaro Murillo describió el clima en el que se hace periodismo hoy en Centroamérica:

Audio de archivo, Álvaro Murillo: Un clima de amenazas, de cárcel, de exilio, de movilidad permanente, de incertidumbre, de acoso, de precariedad y de… Y de muerte. Esta misma semana murió un colega nuestro en Honduras. Obviamente, la forma más extrema de ataque contra los periodistas…

Silvia: Se refería al periodista Javier Antonio Hércules, que fue asesinado por dos hombres en motocicleta el domingo 1 de junio. Hércules cubría noticias locales en el occidente de Honduras, donde lo mataron. Supuestamente estaba bajo protección estatal desde hacía casi dos años, porque había sufrido amenazas y un intento de secuestro.

Eliezer: Cada país de Centroamérica, como dijo Álvaro esa noche, tiene sus propias formas de violencia contra el periodismo, ejecutadas por distintos actores: el crimen organizado, el poder político local, el gobierno nacional, los grandes intereses económicos, el poder judicial. A su lado estaba Quimy de León, una de las fundadoras del medio Prensa Comunitaria de Guatemala. El problema en su país, por ejemplo, no es el gobierno de Bernardo Arévalo, sino lo que todos conocen como “pacto de corruptos”.

Audio de archivo, Quimy de León: Que no es más que una estructura, una red conformada por militares, por narcotraficantes, por criminales, que pretenden seguir capturando el Estado para su beneficio, para enriquecerse o para lograr impunidad.

Silvia: Los medios independientes de Guatemala vienen denunciando desde hace años el secuestro del Poder Judicial y de otros espacios del Estado por parte de esta estructura. El Ministerio Público del país es el órgano que hace el trabajo sucio: se ha dedicado a perseguir penalmente a cualquiera que pueda denunciar o dificultar el saqueo y la impunidad. Entre 2022 y 2024, más de 40 operadores de justicia y al menos 26 periodistas tuvieron que exiliarse del país por la creación de casos falsos, la criminalización y las amenazas.

Audio de archivo, Quimy de León: Entonces, aunque el gobierno es democrático, le es imposible hacer un contrapeso suficiente para que la ciudadanía, la prensa, la gente organizada, autoridades indígenas, comunidades y funcionarios éticos y dignos o decentes puedan evitar ser perseguidos penal y políticamente, puedan ser intimidados y detenidos. Entonces ese es el gran problema que existe en la actualidad.

Eliezer: La victoria de Arévalo, que asumió la presidencia de Guatemala en 2024, después de meses de movilización popular para que se respetara el resultado de las elecciones, no alcanzó para frenar el poder enquistado en el sistema judicial, ni siquiera para equilibrarlo. Uno de los casos más claros es el del periodista José Rubén Zamora, ícono de la lucha contra la corrupción, que sigue preso desde hace más de tres años por causas armadas para silenciarlo. Los periodistas exiliados no tienen ninguna garantía para volver al país, dijo Quimy. Por el contrario: la persecución a la prensa y a los líderes sociales se estaba agravando a medida que se acercaban elecciones clave. En Centroamérica, los medios independientes operan desde hace tiempo en modo de alerta permanente:

Audio de archivo, Quimy de León: Hay tres cosas importantes para nosotros sobrevivir como medios, que el periodismo que hacemos sobreviva, que las personas que lo hacen estén a salvo, estén seguras, estén tranquilas y de esa forma, digamos, lo que nos salva es el principio, pero también el horizonte de seguir haciendo periodismo. Seis periodistas en exilio y una redacción híbrida, en teletrabajo en diferentes territorios. En estas condiciones es cómo superar el terror, cómo superar el miedo, cómo contar esas historias, cómo hacer pausas, cómo descansar, cómo hablar entre nosotros, cómo dialogar. Ese es el tremendo desafío de vivir en contextos como los nuestros.

Eliezer: El título del conversatorio era “Bajo fuego: ¿cómo sobrevive el periodismo centroamericano?”. Y la respuesta más sencilla, hasta ahora, era esta: porque la gente que lo hace no está dispuesta a dejar de hacerlo. Y porque han encontrado cómplices en el camino. Oscar Martínez, que participaba de la mesa como jefe de redacción de El Faro, dijo algo que iba a resultar bastante preciso a la luz de lo que pasó después.

Oscar: Cuando el periodismo ejerce su oficio y publica, hay gente que te busca. No se olviden de que hay gente tan loca como uno en sus países. Hay gente que luego te busca y te cuenta cosas, y gente de toda naturaleza. Hay gente que te busca desde dentro de las corporaciones oficiales. Hay gente que tiene presos políticos, que te terminan contando el calvario que sus familiares pasaron. Pero el ejercicio periodístico profundo siempre hereda cosas, siempre abre puertas.

Eliezer: La mesa terminó a eso de las 9 de la noche. En el público había muchos periodistas nicaragüenses exiliados en Costa Rica. Uno de ellos, al final de todo, dijo esta frase: “Yo daría cualquier cosa en este momento por ser una persona anónima en Nicaragua”. Después, durante el brindis de cierre, pasó algo providencial. Para entenderlo, primero tienen que saber esto: antes de la mesa de clausura del foro hubo otro conversatorio, del que participaba Carlos. Al final de esa charla, al momento de las preguntas, un hombre muy rubio levantó la mano y le pidió si podía hablar sobre la decisión de volver a El Salvador al otro día. Todo el mundo que sabía se puso un poco paranoico, empezando por Carlos, porque todavía no habían dicho nada abiertamente. El hombre explicó que trabajaba en una embajada, escuchó la respuesta, y se quedó a ver la última actividad. Creo que nadie volvió a pensar en él hasta la hora del brindis, cuando se acercó a Óscar, le dijo algo y salieron de la sala.

Silvia: Ese hombre era parte de un cuerpo diplomático, y les pidió hablar en privado porque quería contarles algo: dos fuentes independientes le habían dicho que estaban preparando un despliegue de policía para el aeropuerto de San Salvador esa misma noche, y que iban a ser detenidos cuando llegaran al país. También mencionó algo clave: dos apellidos que, según sus fuentes, estaban a cargo de esos operativos. Esa era, finalmente, una información que podían verificar o rastrear, y no una especulación. Y eso fue lo que hicieron. Asumieron que no podían volver, y se pusieron a hacer periodismo. Así empezaron el exilio. Hacemos una pausa breve y volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Eliezer: El sábado 7 de junio a media mañana, un grupo de periodistas de El Faro estaban reunidos en el patio del hotel, discutiendo un plan para conseguir más información sobre lo que les había dicho el diplomático. También tenían que decidir qué iban a hacer con sus vidas, porque ya no podían tomar ese vuelo. A lo largo del día fueron consiguiendo fragmentos, lo suficiente como para saber que había una lista de nombres que el gobierno se proponía hacer callar cuanto antes, como habían hecho con la abogada Ruth López, y todas las fuentes daban por sentado que ellos estaban bien arriba en esa lista.

Silvia: Ese mismo sábado, a la dos y media de la tarde, a la hora que ellos tenían que estar abordando el avión de vuelta, 12 agentes uniformados y cuatro civiles detuvieron en San Salvador al abogado constitucionalista Enrique Anaya, una de las voces críticas más respetadas contra los abusos del gobierno de Bukele. Cuatro días antes de que fueran a su casa, Anaya prácticamente anticipó lo que iba a pasar en una entrevista de televisión:

Audio de archivo, programa Frente a Frente: Enrique Anaya: Es terrible la cárcel, o sea… es destructora. Yo creo que eso es lo que definitivamente quieren hacer con Ruth, quieren destruirla moralmente. A Ruth y además de eso mandar el mensaje de miedo para todos. Aquel que hable, el que critique, el que no se arrodille ante el ídolo, se va preso.

Conductor: Usted está hablando y está criticando, doctor.

Enrique Anaya: Sí, sí. Y por supuesto que para mí, por supuesto que tengo miedo.

Conductor: ¿Tiene?

Enrique Anaya: Por supuesto. Yo creo que cualquier persona acá que nos atrevemos a hablar, hablamos con miedo, hablamos con temor.

Eliezer: Cuando las cosas se tranquilizaron un poco, Carlos se quedó solo en una mesa para hacer algunas llamadas a El Salvador. Tenía que avisarle a un par de personas lo que sabían, al menos en parte, porque era probable que ellos también estuvieran en esa lista. Gente que había denunciado delitos o actos de corrupción del gobierno, o que ayudaban a víctimas de los abusos del régimen y a sus familias. Carlos les pedía que, por favor, evaluaran cuanto antes irse del país.

Carlos: Se lo digo, uno, por la, por la situación. Y dos, porque ciertas personas en las que confío me han hecho saber que los targets están decididos y que además esta gente va a hacer una barrezón en el menor tiempo posible antes de las elecciones. Entonces… piénselo por favor, porque no, porque no tiene, o sea, no tiene sentido. Mientras le hablo a usted, me hablo para mí porque yo tenía pensado volver hoy al país, Ingrid.

Eliezer: La persona con la que está hablando Carlos es Ingrid Escobar, una de las defensoras de derechos humanos más visibles del país. Ingrid le dice a Carlos que ella sabe el peligro que corre, pero que está en una situación más delicada todavía.

Ingrid Escobar: Yo sé la gravedad que corro de que me metan presa, pasa que yo he sido prediagnosticada ahorita con un cáncer bien agresivo. Entonces, cosa que ya acepté, ya lloré, ya todo. Estoy en un… Es como mil de exámenes que estoy y este… Por eso, no crean que yo no me hubiera ido ya, si yo ya eso lo tenía, o sea pensado por la situación, pero como afuera es carísimo, imagínese uno llega al otro lado valiendo pues, porque la salud en otros lados está peor que aquí por lo caro, verdad… entonces…

Carlos: Ingrid… Y si yo le consigo a usted un contacto que probablemente puede echarle la mano, ¿usted lo valoraría?

Ingrid: Ay, yo sí, yo sí. Ni lo dude.

Carlos: Mire, déjeme por favor hacer una llamada, eh, déjeme ver qué putas hago. No puede ser, Ingrid.

Ingrid: Si, horrible, mire…

Carlos: No puede ser.

Ingrid: Y con mis dos criaturas. Eso si me meten presa, me va a pasar lo de Muyshondt porque me voy a morir, quizás no tanto de presa, pero que no me van a dar el tratamiento.

Silvia: Alejandro Muyshondt, el que menciona Ingrid, era amigo de Bukele y fue nombrado asesor nacional de seguridad por el presidente mismo, hasta que cayó en desgracia. En agosto de 2023, después de denunciar a funcionarios del gobierno por corrupción, fue detenido y acusado de filtrar información clasificada. Fue aislado y torturado, y murió en la cárcel en enero de 2024, afectado por graves problemas de salud. El cuerpo que le entregaron a sus familiares había sido brutalmente golpeado, cortado y perforado.

Carlos: Dios mío, Ingrid, puta…

Ingrid: Sí, está difícil. Y ya que ahí estoy bien fregada, si no el jueves ya me iba, el miércoles me iba ya con mis dos niños, hasta permiso del papá tenía y todo. Pero ahorita…

Carlos: ¿Con los cipotes se iba a ir, Ingrid?

Ingrid: Ya con los niños y yo tengo todo, o sea esa parte, pero como me ha caído esta situación.

Carlos: ¿Cuándo recibió ese diagnóstico, Ingrid?

Ingrid: El 2 de junio. Yo ya vengo desde febrero, pero así, este peor diagnóstico lo recibí el 2 de junio.

Carlos: Vaya, eh… Déjeme ver qué puedo hacer, Ingrid.

Ingrid: Si sabe sabe algo me avisas.

Carlos: Te mando un enorme, enorme, enorme abrazo, vos. Fuerza, fuerza, fuerza, Ingrid.

Ingrid: Gracias.

Carlos: Vaya.

Ingrid: Ahí estamos en comunicación.

Carlos: Vale Ingrid, chao.

Eliezer: Carlos tenía los ojos tan rojos y hundidos que parecía que se le iban a salir por la espalda. Después de cortar se tapó la cara y nos quedamos en silencio. Esperé unos segundos y le pedí que me contara un poco más sobre el trabajo de Ingrid.

Carlos: Esta es la abogada de Socorro Jurídico Humanitario, que es una institución que se creó a sazón del régimen de excepción y que han dado servicios jurídicos a las familias de los capturados durante el régimen. Es muy vocal, Ingrid, además, en redes sociales y es además una líder súper visible de los movimientos de derechos humanos. Es probablemente una de las dos caras más visibles. La otra era Ruth. Y además, está reunía la plata para ayudar a las familias a costear el paquete para los reos. Y van a ir por… Puta madre, puta, Buda…

Silvia: Esta historia, como contamos al principio, empezó cuando El Faro publicó una entrevista a dos líderes pandilleros prófugos que contaban cómo le habían ayudado a conseguir poder político a Bukele a cambio de dinero y privilegios. Eso fue el 1° de mayo. Un día después, el presidente salvadoreño solo atinó a decir que el problema era que “un país sin muertos” no era rentable para las élites globales, ni para las organizaciones de derechos humanos, ni para el magnate George Soros. Bukele dijo que El Salvador ahora era tan seguro que les había hecho perder su negocio, y uno tenía que suponer que por eso había dos líderes criminales, que su mismo gobierno había ayudado a escapar, hablando sobre los pactos que habían mantenido con él durante años.

Eliezer: Esta era, en su intimidad, parte de la élite global de la que hablaba Bukele: un periodista que usaba las mismas tres camisas desde hacía un mes, que acababa de enterarse que no iba a poder volver a su casa para despedirse de su perra agonizante, y una abogada que no podía pagar un tratamiento para el cáncer fuera del país; los dos viendo cómo hacían para reunir los pedazos de sus vidas, al igual que sus familias y sus colegas, porque habían hecho enojar al presidente. Debe ser muy difícil aceptar que tenés que renunciar a todo por el capricho de un señor que tiene un poder tan grande y una piel tan delicada.

Un día después, Iván Olivares, un veterano periodista nicaragüense exiliado en Costa Rica iba a tratar de explicármelo:

Iván Olivares: La emoción del exilio, la sensación, el sentimiento ─no sé cuál es la palabra correcta─ del exilio, es algo que yo defino con una combinación de frustración, de nostalgia y de ira. Pero es una combinación negativa, una combinación de esas tres cosas, que es lo que vivís cuando estás en el exilio y recordás que estás aquí por dos tipos. Dos tipos y sus cómplices.

Silvia: El domingo 8 de junio por la mañana, Carlos, Óscar y una decena de periodistas más se fueron de Costa Rica a otro país que no era su país, a una ciudad donde no estaban sus casas, ni sus hijos, ni sus parejas, sin saber cuándo iban a poder volver. Ese mismo domingo, de madrugada, la abogada Ingrid Escobar pudo salir de El Salvador con sus hijos rumbo a otro país donde consiguió apoyo para continuar su tratamiento médico y su vida sin miedo a ser capturada.

Eliezer: Una semana después, la Asociación de Periodistas de El Salvador, APES, denunció que entre mayo y junio habían documentado el desplazamiento forzado de unos 40 periodistas a causa del hostigamiento y la intimidación del gobierno. Además de El Faro, gente de Factum, de Gato Encerrado, del Diario de Hoy, de Redacción Regional, periodistas y medios independientes de El Salvador que han sido excepcionales para denunciar los abusos y la corrupción del gobierno, habían tenido que salir del país. El mismo presidente de APES, Sergio Arauz, formaba parte de ese grupo. Hacemos una última pausa y volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Eliezer: El fin de semana que vi a mis amigos convertirse en exiliados, entendí algunas cosas sobre el exilio que pensé que sabía, porque había leído o escuchado sobre ellas. Iván Olivares, el periodista nicaragüense que trató de describirme cómo era la sensación del exilio, me dijo que era muy difícil traducir en palabras ciertas emociones: que era como tratar de explicar el miedo a un accidente aéreo que puedes sentir dentro de un avión, a una persona que nunca ha estado dentro de un avión. También me explicó cómo se sentía cuando decidió irse de Nicaragua por primera vez.

Iván Olivares: Es una sensación constante de peligro. Es una sensación que vos estás ahora, podés estar en tu casa o podés estar en un parque, o podés estar escondido o haciendo cosas públicas. No importa. Y es una sensación de peligro constante, de que en algún momento o van a atentar físicamente en contra tuya o van a llegar simplemente llevarte preso porque un día escribiste algo y es una cosa que llega un momento en que decís no puedo más.

Silvia: Ivan tiene 59 años y hace más de 20 que escribe sobre economía para Confidencial, un medio independiente que fue asaltado, ocupado y expropiado por el régimen de Daniel Ortega, que había tratado de silenciarlo de todas las formas posibles. Se fue del país en 2019, después de que la policía ocupara la redacción, pero pudo volver. En 2021 se fue de nuevo, y sintió que esa vez era distinto.

Iván Olivares: Crucé la frontera, venía caminando con alguien que me venía guiando por caminos que yo no conocía y de pronto le dije: ¿Y dónde termina Nicaragua y donde comienza Costa Rica? Y me dijo: ese portón que acabamos de pasar. Y volteé a ver para atrás y me puse a llorar.

Eliezer: A Iván lo conocí el domingo 8 de junio en la Casa para el periodismo libre, un espacio que abrieron la DW Akademie y el Instituto de Prensa y Libertad de Expresión en San José para ofrecer apoyo, asesoramiento y contención a periodistas exiliados en Costa Rica. La idea es ofrecerles herramientas para que puedan seguir haciendo periodismo; que tengan un lugar seguro, un espacio para trabajar y para encontrarse con otros. Ahí conocí también a Arlén Padilla, que se tuvo que ir de Nicaragua en 2021, el mismo año que Iván.

Arlén Padilla: La razón por la que salí fue porque confiscaron por segunda vez para el medio que trabajaba, que era Confidencial. Mi pareja también trabajaba en una fundación que daba información crítica contra el gobierno. También la confiscaron y, aparte de eso, ambos teníamos también involucramiento con movimientos estudiantiles. Entonces estábamos por todos los frentes.

Silvia: Arlén tiene 26 años y se graduó en Ciencias Políticas, pero siempre quiso hacer periodismo. En enero de 2021, cuando consiguió una oportunidad, el contexto estaba muy complicado en el país, porque a finales de ese año había elecciones. En mayo la policía confiscó por segunda vez la redacción de Confidencial. En noviembre de 2021, unos días antes de que Daniel Ortega se reeligiera para su cuarto mandato consecutivo, ella se fue del país.

Arlén Padilla: Y la mayor parte del periodismo que he hecho, lo he hecho desde el exilio.

Eliezer: Claro, porque estuviste 11 meses, 10 meses pudiste hacer periodismo en Nicaragua y después ya…

Arlén: Sí, y después ya. Y de hecho menos, porque desde junio de 2021 ya era prácticamente como tener una metodología de trabajo, de estar prácticamente en el exilio sin estar en el exilio. Dejar de firmar trabajos, tener mucho cuidado con los movimientos, etcétera.

Yo creo que lo que me ayudó un poco era que sentía que al fin estaba haciendo algo que había querido hacer por mucho tiempo. Pero eso no significa que sea más fácil.

Eliezer: Muchos de los periodistas nicaragüenses exiliados en Costa Rica son tan jóvenes como Arlén. Algunos vienen de los movimientos estudiantiles, que fueron la columna vertebral de las protestas contra el régimen y uno de los primeros blancos de la represión. Ese domingo, en San José, a medida que conocía a algunos y les pedía que me contaran sus historias, entendí también que para ellos el periodismo podía ser una respuesta, una posibilidad de resistencia. Una aspiración, y no una carrera truncada por la dictadura.

Carlos Monterrey: Tenía ciertas dudas sobre dar entrevistas porque no creo que tenga una trayectoria periodística como como para decirlo, pero creo que el mismo contexto me ha obligado a hacer cierto periodismo.

Silvia: Él es Carlos Andrés Monterrey. Charly, como le dicen, se tuvo que ir de Nicaragua hace más de siete años. A mediados de 2018 participó de la gran ola de protestas de estudiantes y se atrincheró en la universidad con cientos de compañeros. Fueron atacados por fuerzas paramilitares, se escaparon y se refugiaron en una iglesia. Ahí los asediaron durante 15 horas, hasta que pudieron salir gracias a la intervención de la iglesia y del sector empresarial, pero ya estaban marcados.

Carlos: Fue en un contexto de tiempo donde estaban capturando a todos los jóvenes que se habían manifestado y pasé así en casas de seguridad, hasta que finalmente mi familia, sin mi consentimiento y procurando resguardarme, me exiliaron.

Eliezer: Cuando su familia lo hizo subir a una combi que lo dejó en Costa Rica, Carlos apenas había cursado el primer año de la carrera. Ahora, con 26 años, es una especie de veterano del exilio. Le pregunté, como hacía con todos, qué era lo que más extrañaba de Nicaragua.

Carlos: Es difícil porque después de siete años la realidad se te distorsiona. A veces me doy cuenta que hay direcciones que he olvidado que ya no, ya no las manejo tan fácil. Pero lo que más extraño es la idea que tenía del país en el que vivía. Ahora entiendo que ni el país es el mismo, ni yo soy el mismo. Pero extraño la idea que tenía, de sentirme mi vida que tenía de… Me reconocía como un joven que se quería comer el mundo, súper empoderado, tenía una red de apoyos increíbles y probablemente, quizás eso era de lo que más extraño.

Eliezer: Esa era una respuesta que iba a recibir en diferentes versiones. Una idea a la que se aferraban para mantenerse a flote después de que el avión en el que iban, para usar la metáfora de Iván, hubiera estallado por los aires. La noche del domingo, mientras tomábamos una cerveza en la misma mesa donde había entrevistado a los periodistas de El Faro, una productora audiovisual del medio Divergentes, Alicia Hernández, me dijo que ella y su pareja se repetían aquello como un mantra.

Alicia Hernández: Yo pasé muchísimo tiempo con esa nostalgia de Nicaragua acá, y para mí fue súper difícil eso. Y Miguel me repetía como dos veces a la semana: lo que vos extrañás ya no existe. Y al suave he podido reconciliarme con esa idea, pues. Pero… Pero ha sido muy difícil. Pero eso de “lo que extrañás ya no existe” ha sido una constante desde que nos vinimos al exilio.

Silvia: Alicia tiene 25 años y se fue de Nicaragua a los 17 para estudiar. Mientras estaba afuera, el país que había dejado empezó a desvanecerse. Dos años antes de que terminara sus estudios, su familia ya se había ido a Costa Rica. Ella tuvo que volver al exilio.

Eliezer: Al lado de Alicia estaba Miguel Andrés, su pareja, que también tiene 25 años y es periodista en Divergentes. Miguel se fue de Managua a mediados de 2022, después de que sus padres se hubieran exiliado, pero esa noche me explicó que su experiencia con el exilio había sido distinta.

Miguel Andrés: Porque yo decidí, o sea, como a diferencia de muchas historias, yo decidí exiliarme. Y con las ganas de no regresar a Nicaragua. O sea, yo salí sabiendo que no iba a regresar, pero también sabiendo que no quería regresar, porque como… El momento en el que pude ser lo que quería ser toda mi vida no se me permitió y tal vez en ese momento no me salí porque me estuvieran patrullas, por ser periodista. Pero creo que salí porque quería ser periodista.

Eliezer: Un efecto insospechado de la represión a la prensa es que, en América Central, ha plantado una semilla de obstinación mucho más resistente que la impunidad de un tirano centroamericano promedio. Por supuesto, los efectos que tiene para los medios y los periodistas son destructivos, en un contexto en el que hacer periodismo en condiciones “normales” ya es difícil y precario. Nadie dice lo contrario.

Iván: Es difícil escribir de un país donde no estás. De una realidad que apenas… Eso, que está cambiando y ya no está cambiando con vos. Está siendo cada vez más difícil…

Miguel: Creo que el ser periodista también en el exilio, jode porque sos un riesgo para tu entorno. Como las personas leprosas en su momento.

Iván: Las fuentes que cultivaste por años, en mi caso por décadas, ya no hablan ni los entiendo. A veces uno dice “no te contestan ni el saludo”. En este caso no es una frase, en este caso es una descripción exacta.

Alicia: O sea, incluso la gente que está afuera y que eran fuentes con las que contábamos hace dos años, un año, tienen familia adentro entonces porque tienen miedo y no quieren que le pase nada a sus familiares, ya no te quieren hablar acá, pero ni usando seudónimo.

Iván: Estoy escribiendo, no del país que es en realidad en este momento, sino del país que yo recuerdo. De esa imagen de Nicaragua que se quedó en mi memoria.

Alicia: Todo el mundo está luchando por sobrevivir.

Silvia: Hay ejemplos contundentes en América Latina sobre el impacto que el desplazamiento forzado puede tener sobre el periodismo y el derecho de una sociedad a informarse. Venezuela, por ejemplo, es el país que más periodistas ha expulsado en el continente en la última década. Y un reporte de 2024 sobre la diáspora de la prensa dice que el 60% de casi 200 encuestados han dejado de hacer periodismo.

Eliezer: En Costa Rica, el país que más exiliados de la prensa nicaragüense ha recibido, muchos han tenido que dejar de lado el periodismo y hacer otras cosas para mantenerse, al menos por un tiempo. Además de la escasez laboral, el régimen de Ortega ha extendido su persecución a la diáspora: les ha confiscado sus bienes, les ha quitado la nacionalidad, han hostigado a los familiares que quedaron en Nicaragua. A pesar de eso —o justamente por eso—, la gente con la que hablé quería encontrar la forma de hacer periodismo, o de seguir haciéndolo. Piensen en esto: hay jóvenes que, voluntariamente, en estas condiciones, eligieron dedicarse a este oficio. Y cada vez que les preguntaba si, de haber sabido el desenlace, hubieran elegido lo mismo o hubieran hecho algo diferente, lo que me respondían, de una u otra manera, es que era un poco inevitable.

Alicia: Yo sigo haciendo periodismo, porque, uno, estoy aprendiendo a hacer periodismo y siento que no me puedo rendir ahorita. Pero también porque siento que es mi forma de seguir viva y seguir sintiendo que estoy haciendo algo por la gente, realmente.

Iván: Sí, sí, haría cosas distintas, pero ahora que lo pienso, igual sería la misma persona, solo que ejerciendo otra profesión. Y tal vez igual me hubiera peleado con el gobierno e igual hubiera acabado aquí.

Arlén: No, nunca me he arrepentido y creo que lo … O sea que lo seguiría haciendo y lo y lo volvería a hacer. Todas las veces que tenga que hacerlo lo volvería a hacer. Porque yo creo que sí, que es un compromiso muy, muy grande, que siempre digo que va más allá de uno, va más allá de la profesión. Es algo que simplemente no… Es como respirar.

Rodrigo: Yo creo que yo le hubiera entrado más duro. Ya sabiendo las consecuencias y decir, es inevitable, yo hubiera hecho mucho más. Si, si, si.

Silvia: El último audio se escucha bajito, pero el que habla es Rodrigo, el hermano mayor de Alicia, que también es periodista. Dice esto: que si hubiera sabido que el destierro era inevitable, le hubiera entrado más duro. Que hubiera hecho mucho más.

Eliezer: En el mejor de los casos, el exilio de los periodistas centroamericanos es un camino a la incertidumbre. Pero sostiene una promesa de futuro extraña, basada en la terquedad antes que el optimismo: la persecución a la prensa no va a terminar con el periodismo independiente. Lo que no entienden los líderes autoritarios es que, si le arrebatan el proyecto de vida y de país a tanta gente, algunos van a llenar ese espacio con la búsqueda de revancha. Van a convertir eso en parte de su nuevo proyecto de vida. Van a imaginar, a desarrollar y a probar mil maneras distintas de hacerles rendir cuentas, de exhibir lo que quieren ocultar. Y algunas, en algún momento, van a funcionar. Eso no deja de ser una buena noticia.

Eliezer: Este episodio fue reportado y producido por mí. Lo editó Silvia. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido es de Elías González con música de Remy Lozano.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

Quiero agradecer la ayuda de Clemencia Correa, fundadora de Aluna, una organización que se dedica a fortalecer a personas afectadas por la violencia para que sigan con su trabajo de transformación.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

This episode was produced thanks to the support of Reporters Without Borders, Civil Rights Defenders, Race, Equality and Human Rights Institute, and Free Press Unlimited.

Eliezer Budasoff: In June of this year, over the course of a weekend, I was able to watch in real time as a group of Salvadoran colleagues and friends became exiles. All of this happened within three days, during a journalism conference in Costa Rica, and it started with an interview I didn’t want to do.

Eliezer Budasoff: The first thing I’m going to ask you is if you can introduce yourselves.

Óscar Martínez: I’m Óscar Martínez, Salvadoran journalist and editor-in-chief of ElFaro.net.

Carlos Martínez: I’m Carlos Martínez, reporter for the newspaper ElFaro.net.

Silvia Viñas: You may have heard Carlos and Óscar on other episodes of El hilo. In recent years we’ve spoken several times with them and other journalists from El Faro to help us understand key news from El Salvador: the state of exception, bitcoin, the dismantling of gangs…

Eliezer: At the time of this interview, Carlos and Óscar have been out of their country for more than a month, and they had gone the same amount of time without seeing each other. They met again at this hotel, where we’re now sitting, in the courtyard, with the recorder on the table. It’s a Friday, June 6th, siesta time.

Eliezer Budasoff: Can you tell me where we are right now and why?

Oscar: We’re right now in San José, Costa Rica, in the middle of the Central American Journalism Forum, which has been like the place where we’ve managed to get together with the team again. Several of us left before May 1st of this year, 2025, because we were going to publish interviews with two fugitive gang leaders and we knew that was going to have repercussions.

Silvia: In those videos they published on May 1st, the gang leaders told revealing details about the agreements they had maintained with President Nayib Bukele since he was mayor. They said painful things for Salvadorans, things difficult to cover up, even for the government’s communication machinery. Bukele was furious. We did an episode about that.

Carlos: I think I speak for both of us when I say we left the country underestimating the consequences of this publication. That is, we both left with suitcases for a week and a half.

Eliezer: They immediately realized they had miscalculated. The videos exploded and took social media by storm, the territory where Bukele has built his kingdom.

Oscar: The first days we were away, we learned from two different sources, with internal knowledge of the processes, that seven arrest warrants had been prepared at the Prosecutor’s Office, at least against members of El Faro, right after the publication.

Silvia: Then, things only got worse in El Salvador. Throughout May, Bukele persecuted, repressed, and imprisoned people. And Carlos and Óscar had to keep postponing their return. But at this point, when Eliezer sits down to talk with them, more than 30 days have passed since they left the country, and they’re determined to return. They already have plane tickets to San Salvador for the next day, Saturday, June 7th, just like several other colleagues from the newspaper. We believe there’s a pretty big risk that they’ll be detained when they arrive at the airport, or that authorities will go looking for them at their homes a few days later. That’s why Eliezer is interviewing them.

Eliezer: It’s not the first time they’ve left the country when they’re going to publish a bombshell and return when the storm passes. But this time the situation is different. Two weeks earlier, Bukele’s police had detained Ruth López, one of El Salvador’s main human rights defenders. They went looking for her at her house at midnight, held her incommunicado for 15 days and left her in prison. No one thinks it’s a good time for them to return. The problem is that they know the government wants them out of the country, and a threat isn’t enough for them. If there’s a detention order, as their sources told them, they want to see it.

Óscar: We formally, through a legal representative, requested from the Prosecutor’s Office to know if there were detention orders or crimes or crime reports against seven members of the newspaper, the seven who signed the controversial piece. The prosecutor’s office has already passed the 15 business day deadline to respond and hasn’t responded. We’ve done what the law says must be done in these cases. And with no response, nor any more indications, because the information is completely closed, we’ve started to discuss and we’ve made this decision. There’s no information, we don’t have an arrest warrant we can see. We have the testimonies of those who saw it. And with that information we still don’t want to leave.

Silvia: “We still don’t want to leave,” in this case, means they’re not yet willing to go into exile. Not with that evidence. The night before, they and a group of journalists from El Faro had met to talk one last time with the lawyers who were supporting them from El Salvador, and tell them about the plan to return on Saturday.

Eliezer: The meeting was as encouraging as it could be with the objective information they had. That is: it was depressing. I was sitting there with them, in a half-empty bar, with my head leaning over the table to hear what the lawyers were saying through the speakerphone. They had no news to tell them. They had done what they could to find out if they were accused of anything or if they had arrest warrants, but the Prosecutor’s Office continued not responding. After several technical consultations, Carlos asked the million-dollar question:

Carlos: In your opinion, in the coming days, if we return on Saturday, will we be subject to detention or does it fall within the logic that you’ve been able to observe in the cases you’ve followed, a detention after a week, or after a month and all? We’d really love to hear your opinion on that.

Eliezer: The lawyer said this, almost verbatim: that the problem with that question was that trying to predict what the authorities would do was trying to predict what the president said. And that trying to predict what the president thought or did was like trying to predict an 11 or 12-year-old boy. In other words, a very complicated task.

Silvia: His recommendation, after giving them specific examples about the lack of logic with which the government operates, was that they shouldn’t put their hands in the fire. That with the level of whim, emotion and absence of rationality with which the government makes decisions, there was nothing to prevent them from being detained.

Eliezer: Unfortunately, that wasn’t enough to make them change their minds, because it was still speculation. That’s why we were in the courtyard of a hotel in Costa Rica, at siesta time, recording an interview I didn’t want to do. That is: I was interviewing my friends in case they were put in jail when they returned to their country, just for doing their job well. Like many other people, I didn’t want them to return. I tried to understand why they were making that decision, but deep down, what I wanted to know is why it was so hard to convince them to go into exile. That was, for me, the million-dollar question. Why, for a journalist who has investigated and documented the transformation of his country into an authoritarian regime, is it so difficult to go into exile when that reality catches up with them.

Silvia: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: And I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

The independent press is experiencing a generalized siege in Central America. This is nothing new, nor did it start with Bukele. It’s a process that began in Nicaragua, and has been accelerating since 2018, after the great social uprising in that country, when Daniel Ortega unleashed an open persecution against anyone who dared to speak about his government. And then, against anyone who wanted to tell anything about reality. In the last six years, more than 280 Nicaraguan journalists have been forced into exile, and the regime has closed or confiscated more than 50 media outlets. Most of the territory now falls into the category of “information desert.” Ten of the 15 departments don’t have journalists. Not a single one. Not even a Facebook page with local ads.

Silvia: Ortega´s, who has been in power for almost two consecutive decades, have drawn a roadmap for autocratic projects like Nayib Bukele’s in El Salvador, or for corrupt power groups like those in Guatemala, who pursue the same silence, the same information blockade. Critical journalists in Central America have become like canaries in coal mines that anticipate how their countries are being suffocated. The cost they pay for telling what happens and dismantling the narratives of power is extremely high, but not only for them.

Today: what the exile of people willing to document and denounce it means for a society that is losing its rights.

It’s October 3rd, 2025.

Eliezer: We’ll take a brief pause and come back.

Silvia: We’re back on El hilo.

Eliezer: The afternoon of Friday, June 6th, when I interviewed Carlos and Óscar, they were a few hours away from becoming exiles, but they didn’t know it yet. They were clear that this was coming soon, but they believed they had one more chance to enter the country. And that they would be able to leave afterward.

I asked them directly why they were returning. That had more than one answer, but the first one ran through everything else.

Óscar: I think in El Salvador there are still several journalists—as was seen at Ruth López’s hearing when it was filled with journalists covering that hearing—doing their work. I want to be one of them right now, I want to be doing my work in El Salvador and I prefer, I understand the risk, I’m not naive. I’ve been doing this for years, but I prefer to take that risk for the virtue of being able to execute coverage of a dictatorship that is crushing people from within the country. One day, two days, a week, a month, whatever time is possible.

Carlos: We had to be journalists at a time when El Salvador is plunging into a dictatorship and it seems to me that journalists are, in very brief terms, watchdogs, watchdogs of power, watchdogs of society’s actions. And I believe that’s a responsibility assumed above all in circumstances like these. So I think returning to the country to try to do journalism, as Oscar said, one day, two days, three days, is to gamble and use the centimeters of freedom we have left until the dictatorship closes completely.

Silvia: In that last phrase lived all the tension of that moment: in the belief that they still had a small margin to return, do their work and say goodbye to the country. Carlos measured it in centimeters, Óscar in days.

Eliezer: For me they had no margin at all. It was a conclusion one could reach convincingly by looking at what they themselves published. But of course, I didn’t have to choose between the possibility of being put in jail or giving up my life as I knew it.

Carlos: I think we’re not only gambling the last centimeters to practice the profession, but the last centimeters, probably to say goodbye to everything that is ours, our home, our life, closeness with our loved ones and with our country. And I think that’s also worth it, well…

Eliezer: What have people told you about the return? What have your family members told you? What have your colleagues told you?

Óscar: I don’t know anyone who’s told us to come back. I don’t know if you do. Everyone has told us not to. What happens is that later, when you elaborate the answer and you tell them: Would you leave with this evidence? Would you leave your country, would you leave the essence of your profession, would you leave the place where you execute your creed? And then the answer is more difficult for them. If you believe there’s an opportunity, I’ve asked them to return, as I believe there is, wouldn’t you take it? And at that moment the answer is no longer so direct.

Carlos: Shit, Buda, is that normally exile, or prison under a dictatorship, had been for my generation something that happened to my parents’ generation, in the civil war, under military dictatorships. And then always something that happened to others, to those we saw from afar and supported and about whom we wrote, to people who inhabited satrapies like Nicaragua or Venezuela, you know. Assuming it for yourself is very difficult. Being in the middle of this decision is radically assuming a condition you always imagined in others, and in other times. So assuming yourself an exile also has a series of difficulties regarding your profession, your commitment and the way you find meaning in your work and, moreover, everything you’ve understood as life. Would you stop doing it? That’s it. Would you stop doing it? If you believe you still have, as Oscar says, a few meters to inhabit everything I just said. So it’s not just like that to assume that and it’s not just like that to give up or decide to abandon that overnight, you know. So, if I believe there are a few centimeters, I want to have them, I want to live them.

Eliezer: I asked them two more questions, but it was hard to continue after that. I didn’t have an answer. It was almost 4 p.m. on Friday and the future was too close to think about anything else. In less than 24 hours they had tickets to El Salvador, in a couple of hours was the closing of the Central American Journalism Forum, and right now they had to respond to messages and calls from people close to them who were finding out they were going to return. They hadn’t said anything publicly yet, but the news was already circulating in some closed groups.

That night, when he presented the last activity of the forum, Costa Rican journalist Álvaro Murillo described the climate in which journalism is done today in Central America:

Archive audio, Álvaro Murillo: A climate of threats, of prison, of exile, of permanent mobility, of uncertainty, of harassment, of precariousness and of… death. This same week a colleague of ours died in Honduras. Obviously, the most extreme form of attack against journalists…

Silvia: He was referring to journalist Javier Antonio Hércules, who was murdered by two men on a motorcycle on Sunday, June 1st. Hércules covered local news in western Honduras, where they killed him. He was supposedly under state protection for almost two years, because he had suffered threats and a kidnapping attempt.

Eliezer: Each Central American country, as Álvaro said that night, has its own forms of violence against journalism, executed by different actors: organized crime, local political power, the national government, major economic interests, the judicial power. Next to him was Quimy de León, one of the founders of the media outlet Prensa Comunitaria in Guatemala. The problem in her country, for example, is not Bernardo Arévalo’s government, but what everyone knows as the “pact of the corrupt.”

Archive audio, Quimy de León: Which is nothing more than a structure, a network formed by the military, by drug traffickers, by criminals, who intend to continue capturing the State for their benefit, to enrich themselves or to achieve impunity.

Silvia: Independent media in Guatemala have been denouncing for years the kidnapping of the Judicial Power and other State spaces by this structure. The country’s Public Prosecutor’s Office is the organ that does the dirty work: it has dedicated itself to criminally persecuting anyone who can denounce or hinder the plunder and impunity. Between 2022 and 2024, more than 40 justice operators and at least 26 journalists had to go into exile from the country due to the creation of false cases, criminalization and threats.

Archive audio, Quimy de León: So, although the government is democratic, it’s impossible for it to provide sufficient counterbalance so that citizens, the press, organized people, indigenous authorities, communities and ethical and dignified or decent officials can avoid being persecuted criminally and politically, can be intimidated and detained. So that’s the big problem that exists today.

Eliezer: Arévalo’s victory, who assumed the presidency of Guatemala in 2024, after months of popular mobilization to respect the election results, wasn’t enough to stop the power entrenched in the judicial system, not even to balance it. One of the clearest cases is that of journalist José Rubén Zamora, an icon of the fight against corruption, who remains imprisoned for more than three years for cases fabricated to silence him. Exiled journalists have no guarantee to return to the country, said Quimy. On the contrary: the persecution of the press and social leaders was worsening as key elections approached. In Central America, independent media have been operating for some time in permanent alert mode:

Archive audio, Quimy de León: There are three important things for us to survive as media, for the journalism we do to survive, for the people who do it to be safe, to be secure, to be calm and in that way, let’s say, what saves us is the principle, but also the horizon of continuing to do journalism. Six journalists in exile and a hybrid newsroom, telecommuting in different territories. In these conditions is how to overcome terror, how to overcome fear, how to tell those stories, how to take breaks, how to rest, how to talk among ourselves, how to dialogue. That’s the tremendous challenge of living in contexts like ours.

Eliezer: The title of the conversation was “Under Fire: How Does Central American Journalism Survive?” And the simplest answer, so far, was this: because the people who do it are not willing to stop doing it. And because they have found accomplices along the way. Oscar Martínez, who participated on the panel as editor-in-chief of El Faro, said something that was going to turn out to be quite accurate in light of what happened later.

Oscar: When journalism exercises its profession and publishes, there are people who look for you. Don’t forget that there are people as crazy as you in your countries. There are people who then look for you and tell you things, and people of all kinds. There are people who look for you from within official corporations. There are people who have political prisoners, who end up telling you the ordeal their family members went through. But deep journalistic practice always inherits things, always opens doors.

Eliezer: The panel ended around 9 p.m. In the audience there were many Nicaraguan journalists exiled in Costa Rica. One of them, at the end of everything, said this phrase: “I would give anything right now to be an anonymous person in Nicaragua.” Then, during the closing toast, something providential happened. To understand it, first you need to know this: before the forum’s closing panel there was another conversation, in which Carlos participated. At the end of that talk, at question time, a very blond man raised his hand and asked if he could talk about the decision to return to El Salvador the next day. Everyone who knew got a little paranoid, starting with Carlos, because they hadn’t said anything openly yet. The man explained that he worked at an embassy, heard the answer, and stayed to see the last activity. I don’t think anyone thought about him again until the toast, when he approached Óscar, said something to him and they left the room.

Silvia: That man was part of a diplomatic corps, and he asked to speak privately because he wanted to tell them something: two independent sources had told him that they were preparing a police deployment for the San Salvador airport that same night, and that they would be detained when they arrived in the country. He also mentioned something key: two surnames that, according to his sources, were in charge of those operations. That was, finally, information they could verify or trace, and not speculation. And that’s what they did. They assumed they couldn’t return, and they started doing journalism. That’s how exile began. We’ll take a brief pause and come back.

Silvia: We’re back on El hilo.

Eliezer: On Saturday, June 7th, mid-morning, a group of journalists from El Faro were gathered in the hotel courtyard, discussing a plan to get more information about what the diplomat had told them. They also had to decide what they were going to do with their lives, because they could no longer take that flight. Throughout the day they were getting fragments, enough to know that there was a list of names that the government intended to silence as soon as possible, as they had done with lawyer Ruth López, and all the sources took it for granted that they were high up on that list.

Silvia: That same Saturday, at two-thirty in the afternoon, at the time they were supposed to be boarding the return flight, 12 uniformed agents and four civilians detained constitutional lawyer Enrique Anaya in San Salvador, one of the most respected critical voices against the abuses of Bukele’s government. Four days before they came to his house, Anaya practically anticipated what was going to happen in a television interview:

Archive audio, Frente a Frente program: Enrique Anaya: Prison is terrible, I mean… It’s destructive. I think that’s what they definitely want to do with Ruth, they want to destroy her morally. Ruth and besides that send the message of fear to everyone. Anyone who speaks, who criticizes, who doesn’t kneel before the idol, goes to prison.

Host: You’re speaking and you’re criticizing, doctor.

Enrique Anaya: Yes, yes. And of course for me, of course I’m afraid.

Host: You are?

Enrique Anaya: Of course. I think anyone here who dares to speak, we speak with fear, we speak with apprehension.

Eliezer: When things calmed down a bit, Carlos sat alone at a table to make some calls to El Salvador. He had to let a couple of people know what they knew, at least in part, because it was likely they were also on that list. People who had reported crimes or acts of corruption by the government, or who helped victims of the regime’s abuses and their families. Carlos asked them to please evaluate leaving the country as soon as possible.

Carlos: I’m telling you, one, because of the, because of the situation. And two, because certain people I trust have let me know that the targets are decided and that moreover these people are going to do a sweep in the shortest time possible before the elections. So… please think about it, because it doesn’t, because it doesn’t make sense. While I’m talking to you, I’m talking to myself because I was planning to return to the country today, Ingrid.

Eliezer: The person Carlos is talking to is Ingrid Escobar, one of the country’s most visible human rights defenders. Ingrid tells Carlos that she knows the danger she’s in, but that she’s in an even more delicate situation.

Ingrid Escobar: I know the seriousness of them putting me in prison, the thing is I’ve just been pre-diagnosed with a very aggressive cancer. So, which I’ve already accepted, already cried, everything. I’m in a… It’s like a thousand tests I’m doing and um… That’s why, don’t think I wouldn’t have left already, if I had already thought about it because of the situation, but since abroad is so expensive, imagine you get to the other side being worth nothing, because health in other places is worse than here because of how expensive it is, right… so…

Carlos: Ingrid… And if I get you a contact who can probably help you out, would you consider it?

Ingrid: Oh, I would, I would. Don’t doubt it.

Carlos: Look, let me please make a call, uh, let me see what the fuck I can do. This can’t be, Ingrid.

Ingrid: Yes, horrible, look…

Carlos: This can’t be.

Ingrid: And with my two kids. If they put me in prison, what happened to Muyshondt will happen to me because I’m going to die, maybe not so much from prison, but they won’t give me the treatment.

Silvia: Alejandro Muyshondt, the one Ingrid mentions, was a friend of Bukele’s and was appointed national security advisor by the president himself, until he fell from grace. In August 2023, after denouncing government officials for corruption, he was detained and accused of leaking classified information. He was isolated and tortured, and died in prison in January 2024, affected by serious health problems. The body delivered to his family members had been brutally beaten, cut and perforated.

Carlos: My God, Ingrid, fuck…

Ingrid: Yes, it’s difficult. And since I’m really screwed there, if not I would have left Thursday, I would have left Wednesday with my two kids, I even had permission from their father and everything. But right now…

Carlos: You were going to leave with the kids, Ingrid?

Ingrid: Already with the kids and I have everything, I mean that part, but since this situation has fallen on me.

Carlos: When did you receive that diagnosis, Ingrid?

Ingrid: June 2nd. I’ve been going since February, but like, this worst diagnosis I received on June 2nd.

Carlos: Well, uh… Let me see what I can do, Ingrid.

Ingrid: If you know anything let me know.

Carlos: I send you an enormous, enormous, enormous hug, you. Strength, strength, strength, Ingrid.

Ingrid: Thank you.

Carlos: Okay.

Ingrid: We’re in communication.

Carlos: Okay Ingrid, bye.

Eliezer: Carlos’s eyes were so red and sunken it looked like they were going to pop out his back. After hanging up he covered his face and we remained in silence. I waited a few seconds and asked him to tell me a little more about Ingrid’s work.

Carlos: This is the lawyer from Legal Humanitarian Aid, which is an institution that was created because of the state of exception and that has provided legal services to the families of those captured during the regime. Ingrid is very vocal, also, on social media and is also a super visible leader of human rights movements. She’s probably one of the two most visible faces. The other one was Ruth. And besides, she was raising money to help families pay for packages for the prisoners. And they’re going to go after… Fucking hell, fuck, Buda…

Silvia: This story, as we told at the beginning, began when El Faro published an interview with two fugitive gang leaders who told how they had helped Bukele gain political power in exchange for money and privileges. That was on May 1st. A day later, the Salvadoran president could only say that the problem was that “a country without deaths” was not profitable for global elites, or for human rights organizations, or for magnate George Soros. Bukele said that El Salvador was now so safe that they had made them lose their business, and one had to assume that’s why there were two criminal leaders, whom his own government had helped escape, talking about the pacts they had maintained with him for years.

Eliezer: This was, in its intimacy, part of the global elite Bukele was talking about: a journalist who had been wearing the same three shirts for a month, who had just found out he wouldn’t be able to return home to say goodbye to his dying dog, and a lawyer who couldn’t afford cancer treatment outside the country; both of them seeing how to piece together the fragments of their lives, like their families and their colleagues, because they had made the president angry. It must be very difficult to accept that you have to give up everything because of the whim of a man who has such great power and such delicate skin.

A day later, Iván Olivares, a veteran Nicaraguan journalist exiled in Costa Rica was going to try to explain it to me:

Iván Olivares: The emotion of exile, the sensation, the feeling—I don’t know what the correct word is—of exile, is something I define with a combination of frustration, nostalgia and rage. But it’s a negative combination, a combination of those three things, which is what you experience when you’re in exile and remember that you’re here because of two guys. Two guys and their accomplices.

Silvia: On Sunday morning, June 8th, Carlos, Óscar and a dozen more journalists left Costa Rica for another country that wasn’t their country, to a city where their homes weren’t, nor their children, nor their partners, not knowing when they would be able to return. That same Sunday, at dawn, lawyer Ingrid Escobar was able to leave El Salvador with her children bound for another country where she got support to continue her medical treatment and her life without fear of being captured.

Eliezer: A week later, the Association of Journalists of El Salvador, APES, denounced that between May and June they had documented the forced displacement of about 40 journalists due to government harassment and intimidation. Besides El Faro, people from Factum, from Gato Encerrado, from Diario de Hoy, from Redacción Regional, independent journalists and media from El Salvador who have been exceptional in denouncing government abuses and corruption, had had to leave the country. The president of APES himself, Sergio Arauz, was part of that group. We’ll take one last pause and come back.

Silvia: We’re back on El hilo.

Eliezer: The weekend I saw my friends become exiles, I understood some things about exile that I thought I knew, because I had read or heard about them. Iván Olivares, the Nicaraguan journalist who tried to describe to me what the feeling of exile was like, told me it was very difficult to translate certain emotions into words: that it was like trying to explain the fear of a plane crash that you can feel inside a plane, to a person who has never been inside a plane. He also explained to me how he felt when he decided to leave Nicaragua for the first time.

Iván Olivares: It’s a constant sensation of danger. It’s a sensation that you are now, you can be in your house or you can be in a park, or you can be hidden or doing public things. It doesn’t matter. And it’s a sensation of constant danger, that at some point they’re either going to physically attack you or they’re simply going to come take you prisoner because one day you wrote something and it’s something that reaches a point where you say I can’t anymore.

Silvia: Ivan is 59 years old and for more than 20 years he’s been writing about economics for Confidencial, an independent media outlet that was assaulted, occupied and expropriated by Daniel Ortega’s regime, which had tried to silence it in every possible way. He left the country in 2019, after the police occupied the newsroom, but was able to return. In 2021 he left again, and felt that time was different.

Iván Olivares: I crossed the border, I was walking with someone who was guiding me through paths I didn’t know and suddenly I said to him: And where does Nicaragua end and where does Costa Rica begin? And he told me: that gate we just passed. And I turned to look back and I started to cry.

Eliezer: I met Iván on Sunday, June 8th at the House for Free Journalism, a space opened by DW Akademie and the Institute of Press and Freedom of Expression in San José to offer support, advice and containment to journalists exiled in Costa Rica. The idea is to offer them tools so they can continue doing journalism; so they have a safe place, a space to work and to meet others. There I also met Arlén Padilla, who had to leave Nicaragua in 2021, the same year as Iván.

Arlén Padilla: The reason I left was because they confiscated for the second time the media I worked for, which was Confidencial. My partner also worked in a foundation that gave critical information against the government. They also confiscated it and, apart from that, we both also had involvement with student movements. So we were on all fronts.

Silvia: Arlén is 26 years old and graduated in Political Science, but always wanted to do journalism. In January 2021, when she got an opportunity, the context was very complicated in the country, because at the end of that year there were elections. In May the police confiscated Confidencial’s newsroom for the second time. In November 2021, a few days before Daniel Ortega was reelected for his fourth consecutive term, she left the country.

Arlén Padilla: And most of the journalism I’ve done, I’ve done from exile.

Eliezer: Of course, because you were 11 months, 10 months you could do journalism in Nicaragua and then…

Arlén: Yes, and then. And in fact less, because since June 2021 it was practically like having a work methodology, of being practically in exile without being in exile. Stop signing work, be very careful with movements, etcetera.

I think what helped me a bit was that I felt I was finally doing something I had wanted to do for a long time. But that doesn’t mean it’s easier.

Eliezer: Many of the Nicaraguan journalists exiled in Costa Rica are as young as Arlén. Some come from student movements, which were the backbone of the protests against the regime and one of the first targets of repression. That Sunday, in San José, as I met some of them and asked them to tell me their stories, I also understood that for them journalism could be an answer, a possibility of resistance. An aspiration, and not a career truncated by the dictatorship.

Carlos Monterrey: I had certain doubts about giving interviews because I don’t think I have a journalistic trajectory to speak of, but I think the context itself has forced me to do certain journalism.