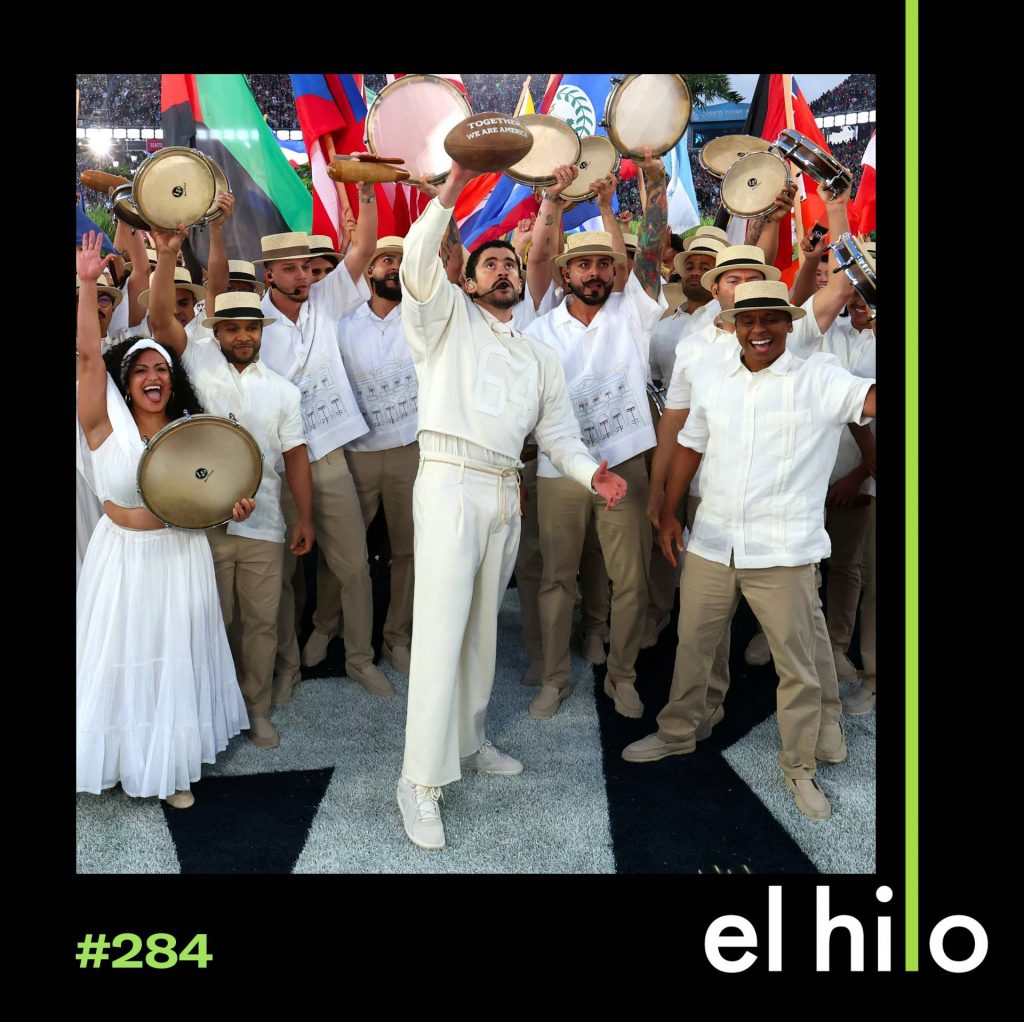

Cuba

Crisis económica

Economía

Bodegas

Pymes

Este episodio se produjo con el apoyo de Civil Rights Defenders, una organización que lleva 40 años trabajando por la defensa de derechos civiles y políticos en los lugares más represivos del mundo.

Cuba atraviesa lo que algunos expertos ya consideran como la peor crisis económica de su historia, la más grave desde los años 90. Hay inflación, apagones que duran días; escasez de combustible, de alimentos, de medicinas. Mientras las bodegas que ofrecen comida subsidiada se vacían, en la isla se multiplican las tiendas y empresas privadas que ofrecen productos y servicios que el Estado ya no puede proporcionar, pero sólo para el que puede pagarlos. Nuestra productora Mariana Zúñiga viajó a La Habana para entender cómo se compara esta crisis económica con la otra gran crisis en la memoria colectiva de los cubanos, y por qué, para los que viven en la isla, se trata de algo más que de la escasez, que siempre ha existido. Ahora la situación parece agravada por un fenómeno que se ha agudizado en los últimos años: la desigualdad.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Mariana Zúñiga -

Reportería

Mariana Zúñiga, Eileen Sosin -

Edición

Silvia Viñas, Eliezer Budasoff, Daniel Alarcón -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción en redes sociales

Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elias González -

Música

Elias González y Remy Lozano -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

Fotografía

Getty Images / Jen Golbeck

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Mariana: En toda latinoamérica ves desigualdad, ¿no? pero el fenómeno aquí pareciera ser más reciente. Y las diferencias como que se hacen más grandes cada día.

Eliezer Budasoff: En febrero de este año, nuestra productora Mariana Zúñiga viajó a Cuba.

Mariana: Es un lugar con muchos contrastes. Muchos de ellos son chocantes. Por ejemplo, vi muchos carros viejos, soviéticos, en la calle. Y de repente ves dos o tres camionetas nuevas Un ejemplo que retrata muy bien el contraste que se vive en Cuba me lo mostró Pedro, el guía turístico con el que tomé un tour por La Habana Vieja.

Silvia Viñas: Bueno, Pedro no es su nombre real. Lo cambiamos para proteger su identidad.

Mariana: Estábamos caminando y nos topamos de frente con una bodega.

Pedro: ¿Sabes ya qué es esto? ¿Lo que son las bodegas? ¿Ya las conoces, ya? que son los lugares estos estatales donde vienen suministros todos los meses y con una libreta que están anotadas las personas, les dan una cantidad fija y tal y bueno que casi no alcanza, pero es como algo que alivia un poco la situación.

Eliezer: Porque venden más barato de lo que se encuentra en el mercado. Lo que pasa es que todo lo venden racionado.

Pedro: Y bueno, es como un pequeño respiro, pero la verdad es que bueno, es como un respiro muy corto.

Mariana: Esta bodega estaba vacía, oscura y apenas tenía un par de productos en los estantes. Si mal no recuerdo, eran botellas de jabón para limpiar el piso y luego a la derecha, del otro lado de la acera había un mercadito privado, que en Cuba se les conoce como pymes.

Silvia: Es probable que en su país también usen este término: pymes, para referirse a las pequeñas y medianas empresas.

Pedro: Entonces, en contraste está esto. Esto sí es una pyme, ¿ves? que fíjate que tiene muchos más productos y son las que importan.

Mariana: La tienda estaba limpia, iluminada y mucho mejor surtida. Tenía huevos, pasta, papitas de bolsa, crema para el pelo y otros productos de cuidado personal.

Pedro: Cuando surgen este tipo de cosas como mipyme, el contraste es muy fuerte y casi que que han generado una contradicción en la ciudad y es la siguiente: De no existir las pymes, entonces no habrían determinados productos. Entonces, dicen: no porque las pymes generan desigualdad. Pero la cuestión está en que viene la contraparte, pero si no están ahora mismo estamos más desabastecidos.

Pero no es que la pyme genere más desigualdad, se hace más evidente. Ya la desigualdad existe

Eliezer: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Estudios. Soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: Y yo soy Silvia Viñas.

Mientras las bodegas que ofrecen comida subsidiada se vacían, en la isla se multiplican las tiendas y empresas privadas que ofrecen productos y servicios que el Estado ya no puede proporcionar… pero solo para el que puede pagarlos.

Hoy, Cuba atraviesa lo que algunos expertos ya consideran como la peor crisis económica de su historia, la más grave desde los años 90, y para los que viven en la isla se trata de algo más que de la escasez, que siempre ha existido. Ahora, la situación parece agravada por un fenómeno que se ha agudizado en los últimos años: la desigualdad.

Es 25 de abril de 2025

Eliezer: Mariana, ¿esta fue la primera vez que viajabas a Cuba? ¿Cuál fue tu primera impresión?

Mariana: Sí, esta fue mi primera vez en Cuba. Estuve siete días y mi primera impresión fue que todos hablan de “lo mal que está la cosa”. Todos los días, en todo momento y en cualquier lugar. “La cosa” es como esta cosa, valga la redundancia, omnipresente que está en todos lados.

En el transporte, en los mercados, en la calle, en la iglesia. Es realmente difícil escapar del tema. Y de la crisis en sí, porque está en todas partes. Hay una escasez de alimentos crónica. Los salarios son muy bajos. La gente dice que todo está extremadamente caro.

Silvia: Al cierre de este episodio, el precio de un cartón de 30 huevos estaba en hasta 2.500 pesos. El kilo de arroz en 750 pesos y el paquete de pollo en 1.560.

Eliezer: Para entender lo que significan esos precios para la mayoría de los cubanos, hay que tener en cuenta que el salario mínimo está fijado en 2.100 pesos mensuales desde 2020, que equivalen más o menos a 6 dólares. Es decir, sólo alcanza para comprar el paquete de pollo, o el kilo de arroz. Ambas cosas no se pueden. Y para el cartón de huevos ni siquiera alcanza.

Mariana: No hay suficiente gasolina. En los hospitales tampoco hay suficientes insumos. Y la crisis eléctrica es grave. En algunos lugares los apagones son diarios y pueden durar horas.

Silvia: El marzo pasado hubo un apagón nacional. Y el país se quedó completamente a oscuras. Era la cuarta vez en seis meses que pasaba.

Mariana: Cuba ha estado en crisis por mucho tiempo, pero en este momento pareciera haber un consenso y es que esta crisis es peor que la que se vivió durante el periodo especial. Esto lo hablé con varias personas y casi todas dijeron lo mismo. Cuando hablo del período especial me refiero a principios de los 90, cuando desapareció el campo socialista y cae la Unión Soviética. En ese momento Cuba se vio muy afectada económicamente porque por años la Unión Soviética le dio a Cuba un montón de ayuda y esto hacía que la economía cubana se mantuviera a flote. Pero una vez que cae la Unión Soviética, toda esta ayuda desapareció. El desabastecimiento fue brutal y la gente que lo vivió lo describe con tanto horror que me parecía difícil que esta crisis fuese peor. Así que fui a hablar de esto con Juan Carlos Albizu Campos. Él es economista y demógrafo.

Mariana: Hola

Juan Carlos: ¿Llegaron bien?

Mariana: Sí

Juan Carlos: Que bueno.

Mariana: Fuimos hasta su casa y justamente recuerdo que al llegar no había luz.

Juan Carlos: Estamos sin electricidad.

Mariana: Me imagino que esta pregunta te la han hecho un montón, pero bueno, ¿tú dirías que esta crisis es mejor, o peor, igual, comparable con el periodo especial?

Juan Carlos: Tal como yo lo veo, esta crisis es mucho peor.

Mariana: Juan Carlos me dijo y más o menos así lo entendí, que esta situación es el resultado de varias crisis juntas.

Juan Carlos: No es una crisis clásica, es lo que se llama un modelo de policrisis. Porque está montada sobre crisis que se venían arrastrando. Primero la crisis económica propia que produce el confinamiento y el cierre, el virtual cierre del sector turístico. Y todo eso montado con los efectos de la crisis financiera internacional que empieza en el 2008, y que en Cuba provoca una crisis financiera. Es decir, por eso es una cascada, es una crisis montada sobre otra, que no es el caso del periodo especial.

Mariana: Juan Carlos también me dijo que ahora la situación es más compleja porque en ese momento Cuba tenía cosas que hoy ya no tiene.

Juan Carlos: Muchas industrias, muchos procesos productivos que desaparecieron, que en aquella época no. Entonces había unas opciones de inversión y unas opciones de desarrollo que hoy no existen.

Mariana: También me dijo que en ese momento la crisis fue realmente puntual.

Juan Carlos: La crisis, verdaderamente la fase crítica dura 91, 92, 93 y 94. Luego ya empieza la reanimación.

Mariana: Mientras que ahora la crisis ha sido muy larga. Además, antes el país tampoco estaba tan endeudado como ahora. Y la otra gran diferencia es que hoy en día las tiendas en Cuba no están del todo vacías como lo estaban en ese momento.

Juan Carlos: Lo que había era una crisis de escasez, una crisis de suministro muy fuerte. Ese es el otro tema. En este caso se ha entretejido un sector emergente, de carácter privado, que en el período especial no existía. Ese sector lo que ha hecho es suplantar al Estado en las áreas donde el Estado se ha retirado.

Mariana: Entonces, toda esta situación ha terminado por causar, o por hacer más evidente, la desigualdad en el país.

Silvia: Ya, antes, en el periodo especial no había tanta desigualdad.

Mariana: Al menos en ese momento todo el mundo podía acceder a lo mismo. Entonces, eso hacía que la sociedad pareciera más igualitaria.

Yo quería entender un poco más cuál era el rol de la empresa privada en Cuba. Entonces, hablé con este señor que se llama Oscar.

Oscar: Mi nombre es Oscar Fernández. Yo soy economista y cuento corto es que en la pandemia inicié este emprendimiento que se ha convertido en una empresa, en una pequeña empresa, que resultó ser la primera empresa cubana en exportar frutas deshidratadas.

Mariana: Y él me dijo que ahora se está viviendo en Cuba un momento único.

Oscar: Si tú viajas al pasado y vas cuatro años, cinco años atrás y le dices a los cubanos: mira, yo vengo del 2025 y en el 2025 ustedes van a tener 11.000 empresas privadas registradas, esas empresas van a importar mil millones de dólares, algunos de ellos de Estados Unidos incluso. Nadie te hubiera creído porque era algo que: eso no va a pasar nunca aquí en este país. Y pasó.

Silvia: Claro, porque cuando uno piensa en Cuba que es un país comunista, no te imaginas muchas empresas privadas. Pero, ¿hay otras razones por las cuales Óscar veía como tan lejano, o imposible, que Cuba tuviera miles de empresas privadas?

Mariana: Sí, en el caso de la empresa privada pasa lo mismo que con otros temas económicos. Cuando parece que la cosa avanza, meten el freno y dan marcha atrás.

Oscar: Siempre ha habido la concepción por parte del Gobierno de que el sector privado es un mal. A veces ha sido entendido como un mal necesario. A veces han tenido la intención de barrerlo completamente.

Mariana: Esto ya ha pasado muchas veces. Pasó en los 90, durante el periodo especial. En ese momento le permitieron a muchas personas trabajar por cuenta propia. Profesiones como limpiabotas o manicuristas, por ejemplo. Y luego, cuando hubo una recuperación económica, se echaron para atrás. Lo mismo pasó durante la era de Raúl Castro. Se expandió la lista de actividades que se podían hacer de manera privada y luego, de nuevo recularon. Hasta que llegó el 2021.

Oscar: La pandemia lo cambia todo en todos los lugares del mundo. Aquí hay una situación, que genera una situación social, un contexto social que canalizó de alguna manera en unas protestas masivas el 11 de julio.

Audio archivo, protestas 11J

Manifestantes: Libertad, libertad, libertad…

Mariana: La gente sale a la calle. Sale a la calle a protestar, de una manera que no había ocurrido en años, décadas. Y en ese momento, pues, Oscar dice que el gobierno se vio forzado a tomar una decisión.

Oscar: Entonces, una de las cosas que se hizo fue que primero se autorizó la creación de pequeñas empresas por primera vez. Eso es histórico en Cuba y lo segundo es que cambiaron la lista y ahora el gobierno, en lugar de tener una lista de actividades permitidas, lo que hizo fue emitir una lista de actividades prohibidas,

Eliezer: ¿A qué se refiere Oscar con actividades prohibidas? ¿Cuáles son?

Mariana: Todo lo que tenga que ver con medios de comunicación y periodismo. Todo lo que tenga que ver con la salud y educación. Cosas como minería, producción de azúcar y tabaco. Algunas actividades culturales, como edición de libros. Actividades deportivas. Todo lo que tiene que ver con la ciencia y la investigación. Ese tipo de cosas están prohibidas, lo cual quiere decir que todo lo demás se puede hacer.

Eliezer: Ahora, tú nos contabas que en períodos de crisis el Estado suele recurrir o, a los emprendedores privados, o a la empresa privada para que se encarguen de las cosas que ellos no pueden hacer, ¿no? Esto está pasando ahora mismo y por eso Oscar puede tener su negocio. Pero, qué pasó, por qué el Estado ya no puede encargarse de esas cosas, como por ejemplo, traer comida.

Mariana: Bueno, pues sencillamente porque no tienen plata y no tienen dinero por múltiples razones. Pero una de ellas es que la pandemia paralizó el turismo en la isla y el país nunca se llegó a recuperar.

Silvia: ¿Y por qué no se recuperó el turismo?

Mariana: Yo creo que por la misma crisis que se vive. Los apagones y la escasez. Cuba no es un destino turístico tan atractivo. O sea, ir a un lugar y que no haya luz. O que vayas al buffet en la mañana y pidas un huevo y que no te lo puedan dar. Son cosas que a la gente los hace dudar, ¿no? antes de ir. Además, en el primer gobierno de Donald Trump metieron al país en una lista de países patrocinadores del terrorismo, lo cual hace que otros países, en Europa por ejemplo, duden en ir a Cuba porque después van a tener problemas con su visado para ir a Estados Unidos.

Oscar: El gobierno se quedó sin dólares. Porque los hoteles no dan y porque el turismo está cerrado. Porque las sanciones se incrementaron, porque han dejado perder industrias por mala gestión de las inversiones, por lo que sea.

Mariana: Entonces, el Estado ya no tiene suficiente dinero para traer comida. Como por ejemplo, el pan.

Oscar: Ahora un pan que valía 10 pesos, vale 100. Ahí lo que pasó en realidad es que el gobierno retiró el subsidio por tasa de cambio que tenía la harina.

Mariana: Ok, esto que acaba de decir Oscar vale la pena explicarlo. En Cuba no se produce harina. Hay que importarla, pero no hay dinero para importar esa harina. Entonces, los negocios privados – las pymes – son las que importan la harina y hacen el pan. Pero como en Cuba hay controles cambiarios, a las pymes les cuesta más dinero comprar la harina. ¿Por qué? Porque no pueden comprar dólares al precio oficial. Entonces, tienen que ir al mercado informal donde los dólares son muchísimo más caros. La consecuencia de toda esta explicación, que puede sonar un poco enredada, es que: El pan sube de precio.

Óscar: Entonces, ¿qué pasa? Que el salario de este trabajador está todavía old fashion, está todavía para el pan de 10 pesos. Por supuesto que no alcanza para el de 100.

Silvia: Bueno, me imagino que el pan no es lo único que ahora está más caro, ¿no? ¿Cómo ha afectado el aumento en los precios a las personas?

Mariana: Bueno, mucha gente simplemente pasa hambre, no come lo suficiente, o come menos. Y lo segundo es que la gente empieza a culpar a los negocios privados de los altos precios.

Oscar: Interpretación de la población: coño de su madre, los privados están abusando. Se están haciendo ricos con eso.

Mariana: Y el gobierno pues ni lerdo ni perezoso que es, se aprovecha esta narrativa para que no lo culpen a él. Y bueno, si vas a la prensa nacional encuentras muchos artículos donde se sataniza al sector privado, donde dicen que no pagan impuestos, donde los culpan por la inflación.

La realidad es que si los precios suben, el culpable no es el dueño de la pyme. El culpable es toda la distorsión económica que existe y ha existido, y las decisiones económicas que ha tomado el gobierno por demasiado tiempo.

Eliezer: Mariana, además de esto de bueno, de satanizarlo, digamos en en la prensa y en el discurso público, nos decías que también esto había pasado antes, ¿no? Ahora el Estado, también está de alguna manera frenando la actividad de la empresa privada.

Mariana: Un poco, sí. Por ejemplo, el año pasado habían personas que tenían licencia para vender como mayoristas y de un día para otro se despertaron y ya no tenían la licencia. El papelito que tenían ya no era válido. Ese es el tipo de incertidumbre con la que viven los que hoy en día manejan este tipo de negocios. Para ellos siempre existe la posibilidad de que el gobierno recule de nuevo y de que el sector privado pierda un poco el terreno que ha ganado en los últimos años.

Silvia: Claro pero, o sea, las pymes sobreviven, es porque hay gente que sí puede comprar. ¿Quiénes son estas personas que pueden pagar estos precios tan altos?

Mariana: Básicamente son las personas que trabajan en el sector privado o las personas que reciben remesas de algún familiar que emigró.

Leonel: Principalmente los clientes son cubanos que emigraron, por razones económicas, políticas, lo que sea, pero mantienen una fuerte conexión emocional con familiares y amigos aquí en Cuba.

Mariana: En La Habana tuve la oportunidad de conocer a Leonel, que es el dueño de un mercadito online. Una tienda online, llamada Isla 360, que importa productos desde Estados Unidos, desde España o desde México.

Leonel: Inicialmente empezó como una tienda de regalos. Lo que pasa es que la crisis después de la pandemia, fue puramente de alimentos. Entonces el público cada vez nos pedía más y ahora mismo estamos muy especializados en el mercado de alimentos y aseo.

Mariana: Cuando te metes en la página, hay productos como: sopas estilo ramen, gel de baño, té de menta, mermelada de fresa, desodorantes. Pero también hay productos básicos, de esos que la gente solía encontrar en la bodega y que hoy escasean.

Eliezer: Quizás el símbolo más potente de la profundidad de la crisis sean las importaciones. Cuba solía ser el mayor exportador de azúcar en el mundo. Ahora importa azúcar. También importa café, cerdo y granos.

Leonel: Y productos que históricamente aquí no había habido necesidad de importar porque realmente había una producción interna que cubría eso. Ha habido que importarlo. Nosotros nunca pensamos que ver importaciones de huevo, por ejemplo. Nunca pensamos que se importara agua. Nunca pensamos que se importara sal. Estamos rodeados de sal.

Silvia: Se estima que más del 70% de la comida que se consume en Cuba viene de afuera.

Eliezer: Después de la pausa vamos al campo para entender por qué es tan complicado sembrar en Cuba.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo. Queríamos ver cómo la crisis económica estaba afectando a los cubanos que producen comida en la isla. Mariana viajó casi tres horas desde La Habana a la provincia de Pinar del Río para conocer a uno de ellos.

Mariana: Durante el camino me llamó la atención que había muy pocos carros en la carretera.

Chofer: Generalmente son transportes colectivos.

Mariana: Y nuestro chofer que acostumbra a tomar esa vía me dijo que eso era normal.

Chofer: Por la cuestión de la gasolina. Cuando sales de La Habana en casi ningún lugar hay gasolina.

Mariana: ¿Y tú tuviste que hacer mucha cola para poner el tanque esta vez?

Chofer: Sí, eso son horas. Te metes dos, tres horas, cuatro horas y un día entero en una cola de esas.

Mariana: Ese viaje lo hicimos para ver a Isabel y a su tío Miguel. No son los verdaderos nombres de estas personas. Los cambiamos también por seguridad.

Mariana: Estuvimos tres horas en carretera más o menos. Y cuando llegamos, o cuando pensamos que llegamos al lugar, en realidad tuvimos que subirnos a un tractor porque nuestro auto era muy bajito y el camino estaba muy malo.

Miguel: Hacía falta un carro con más fuerza, ¿ve? Porque el camino está malísimo. Llovió mucho este año y no se ha podido arreglar por problemas económicos.

Mariana: En ese trayecto Isabel, la sobrina de Miguel, nos contó cómo han ido cambiando las cosas.

Isabel: Esto antes todo era caña. Cultivos de caña que ya por su puesto se ve que no…

Mariana: ¿Hace cuánto que no se cultiva caña por acá?

Isabel: Más de 10 años

Eliezer: ¿Cómo es la finca de De Miguel? ¿Qué siembran?

Mariana: Bueno, esta es una finca grande. Tiene vista al mar y aquí se siembran cosas como papaya, tomates, ajo, yuca, guayabas.

Miguel: Para que se lleven fruta para La Habana.

Mariana: Pero sobre todo mango. La finca está llena de matas de mango.

Miguel: Ven, está que está aquí mira. Estas de aquí están mejores.

Mariana: Miguel es un hombre de 63 años. En su familia lo describen como una persona soñadora, lo cual se podría decir que es raro porque la vida en el campo es muy complicada. Primero tiene problemas para regar. El riego en su finca es eléctrica. Entonces cuando se va la luz, pues, evidentemente no puede y cuando vuelve a veces no hay ni siquiera suficiente voltaje para que los equipos funcionen.

Miguel: Y a veces eso nos da una afectación grande en la producción porque son plantas pequeñas que sí necesitan de riego. El frijol, el maíz, la frutabomba. Esas plantas sufren mucho. El tomate, el boniato que necesitan de riego permanente. Y en esta época del año que hay más sequía es cuando más se nota la falta de riego.

Mariana: Segundo, en el país no hay suficiente dinero para comprar abonos químicos, que son los productos que se necesitan para producir. Tampoco hay dinero para comprar materiales como, por ejemplo, limas para afilar los machetes.

Miguel: Buscamos métodos alternativos, montamos piedras en motores eléctricos para afilar los machetes, eso que está ahí. Una Lima está costando mil y pico de pesos y entonces no son limas de alta calidad.

Mariana: Pero creo que quizás lo más complicado o el problema más grande que tienen es la falta de gasolina.

Miguel: Todas las producciones tenemos que transportarlas y comercializarlas a larga distancia. Nosotros producimos alrededor de 600 toneladas, que casi todas hay que transportarla a más de 70 o 80 kilómetros para la alimentación del pueblo. Entonces, ¿qué pasa? que cuando no contamos con el combustible necesario y el transporte necesario para comercializarla, pues ya se pasan. Y esa fruta se pierde. Nos ha pasado, nos ha pasado porque hemos perdido cientos de quintales

Mariana: La falta de gasolina también hace que el producto llegue a las ciudades con un precio muy elevado, porque pasa por muchas manos y en el trayecto va subiendo.

Miguel: El tomate lo vendió aquí a 20 pesos y entonces llegó a La Habana a 80 pesos. Mira qué diferencia hay de 20 a 80.

Y algo muy importante en el campo, que no hay tanta producción y demás es falta de salario. Porque en el campo si no hay producción, no hay salario. Entonces, al haber ese desequilibrio, no da motivación a trabajar en el campo.

Silvia: Y entonces ¿qué cree Miguel que se puede hacer? ¿Cuál sería la solución?

Mariana: Para Miguel el gobierno tiene que encontrar una manera, no sabe cuál, de incentivar la producción en el campo.

Miguel: Esa es la única forma que hay para mantener vivo al pueblo de Cuba, producir alimento, que exista alimento en la mesa del cubano. Porque no podemos seguir pensando en el barco, en la exportación, porque el país no tiene dinero suficiente para comprarlo. El alimento existe, pero no tiene las condiciones del país.

Mariana: Pero, lamentablemente apostar por la agricultura no parece ser algo que está en los planes del gobierno. El gobierno sigue apostando por el turismo y las actividades que giran alrededor de esto. El año pasado, el país invirtió 4,6 veces más en la construcción de hoteles que en otros sectores, como por ejemplo, la agricultura. Y esta es una de las grandes incógnitas que tienen los cubanos. ¿Por qué el Gobierno sigue apostando por un sector que está en declive, mientras que la gente no tiene que comer? Y bueno, la respuesta nadie la sabe realmente.

Eliezer: Claro, pero ¿qué está haciendo el gobierno para reactivar la economía? ¿En realidad está haciendo algo respecto de la crisis económica que no sea construir hoteles y poner límites?

Mariana: Pareciera que no. De alguna manera hay ciertas cosas a las que ellos quieren acudir para poder captar más divisas. Una de ellas es la dolarización. Están intentando de alguna manera dolarizar de a poco el país y una de esas maneras ha sido con la creación de tiendas en las que las personas pueden ir y únicamente se paga en dólares. Esa es como una manera de captar ese dinero o esos dólares que ellos no reciben, ¿no?

Pero los economistas dicen que bueno, que no creen que esto tenga mucho cambio ni que tampoco tenga mucho efecto. De hecho, Juan Carlos, el economista con el que hablé y que escuchamos al principio, es una persona que piensa que simplemente el problema es el modelo. Él dice que el modelo es disfuncional y que ni siquiera es reformable. Él lo describe como una persona que está en estado terminal, postrado en una cama. De esas personas que los médicos se preguntan cómo sigue sobreviviendo, pero nadie sabe. Y que va a llegar un momento en que no puede sobrevivir más. Pero no sabía decirme cuánto durará el enfermo.

Silvia: Nos decías que la gente que puede comprar los productos que han subido tanto de precio usualmente tienen su propio negocio o reciben remesas. Pero nos preguntamos ¿qué pasa con los demás? Por ejemplo, las personas que trabajan para el Estado y su única entrada económica es su salario.

Mariana: Los demás lo tienen realmente muy difícil. Cada día se hacen más notorias las diferencias entre los que tienen y los que no. Durante mi visita conocí a Claudia. Ella es bióloga y como ella es científica, trabaja para una institución del Estado.

Claudia: Acá los científicos no son bien remunerados para nada. El salario es bajo. Mi salario es 5.000 y tantos, casi 6.000.

Mariana: Esos son alrededor de 17 dólares al mes, más o menos.

Claudia: Eso no es nada. Y soy investigadora auxiliar.

Mariana: Ni su salario ni el de su esposo, que también es científico, alcanzan para sobrevivir. Pero Claudia, como muchos otros cubanos, vive en familia. Vive con sus suegros.

Claudia: Tengo la suerte de estar en una familia donde todos nos ayudamos y el salario de todos va en función de la casa y así es como sobrevivimos.

Mariana: Además, en su casa no son solo cuatro bocas las que comen, son seis.

Mariana: Claudia también es mamá, tiene un par de gemelos, o jimaguas, como se le dice en Cuba.

Claudia: Ellos son unos terremotos. Van a cumplir cuatro años ahora, pero son bien avispados, son tremendos y es muy cómico, porque son bien diferentes los dos.

Silvia: Ser mamá siempre viene con sus retos, pero estoy pensando en Claudia, en la situación en la que está. ¿Te habló algo sobre cómo es ser mamá en en esta situación en la que está pasando Cuba?

Mariana: Hay un agotamiento físico, económico y emocional. Y también, según lo que me contó Claudia, hay una especie de culpa.

Claudia: Ay, es un sentimiento muy complicado. Tengo muchas contradicciones internas con relación a la maternidad, porque no sé si es por el hecho de que hayan sido jimaguas, pero me ha sido difícil. He dicho: Ay, como arrepentida de haber sido madre y entonces yo misma me culpo por sentir eso y luego los adoro. Son mis adorados tormentos.

Claudia: Es difícil. Es todo un reto por el hecho primero, de que el salario no alcanza. Ser padres es una responsabilidad porque esos niños dependen de ti. Es nuestra responsabilidad que se alimenten bien y es complicado esa dieta balanceada. Y no, no está garantizado en la canasta básica, en la en la bodega, como decimos aquí. Ya cada vez son menos los productos que dan, entonces es más lo que hay que buscar afuera en el mercado para que tengan esa dieta balanceada. La misma leche, hoy fui a buscarla, pero hacía un montón que no venía la leche.

Mariana: Es probable que la situación empeore porque en diciembre el gobierno anunció que este año se van a eliminar progresivamente los subsidios de la canasta básica. Es decir, que la libreta de abastecimiento va a dejar de existir. Y si bien ya muchos productos habían desaparecido, pues, la gente teme que la eliminación de la libreta profundice aún más las desigualdades que existen, ¿no?

Claudia: Todo es un problema por cómo elaborar los alimentos. Aquí tenemos olla arrocera. Tenemos la la olla reina, como le decimos, que es eléctrica. Pero si no hay electricidad, entonces hay que recurrir al gas. Pero es que el gas también ha llegado a ser un problema porque nos hemos quedado sin balón de gas. No hay cómo conseguirlo. Entonces hemos tenido hasta que cocinar al carbón.

Mariana: Para Claudia es muy importante que sus hijos coman proteínas, por ejemplo, todos los días. Así que se consiguieron un par de gallinas ponedoras que ahora viven en su jardín.

Claudia: Y así llegó la primera gallina. Llegó la otra. Ya vamos por cuatro y de verdad que ayudan. En tres días, o en dos, ya tenemos como seis huevos. Y sí, sí, las gallinas ayudan mucho. Las gallinitas de los huevos de oro.

Claudia: Lo que estoy es tratando de echar para pa lante. De resolver, de ver por qué vía y bueno… Tratamos de no tampoco hacer de eso el todo. Sí nos desahogamos, lo hablamos, pero bueno, ya. Y los niños, yo creo que es lo fundamental, porque ellos son el centro de nuestra vida, de nuestra casa, Entonces todo lo ponemos alrededor de ellos, son muy divertidos, son niños, son ruidosos. Pero, o sea, te llenan, ¿no?

Eliezer: Mariana, como a pesar de esto, del bajo salario y de todas las dificultades que tiene Claudia no parece tener planes, no nos has contado si tienes planes de abandonar su trabajo en el sector estatal, ¿no?

Mariana: No. Claudia no tiene intenciones, por el momento, de dejar su trabajo. Porque a pesar de todo, creo que ser bióloga la hace sentir realizada. Pero sí conocí a alguien que lo hizo. Su nombre es Ángel.

Angel: Joven de 25 años, graduado de medicina. Que actualmente estoy desvinculado de esa vida laboral. Y bueno, me gano la vida trabajando, haciendo trabajos en el carro de taxista.

Silvia: Antes de tomar esta decisión, de no ejercer, cómo era su vida como estudiante de medicina.

Mariana: Él estaba contento. A él le gustaba su vida como estudiante, como médico y viendo pacientes, pero realmente estaba llena de frustraciones. Y él se frustraba cuando los pacientes llegaban a la consulta y no tenía insumos para atenderlos.

Angel: Tengo anécdotas de pacientes que han llegado a mi consulta con muchos vómitos y diarrea. Deshidratadas y lo único que tengo es un suero para ponerles, no puedo parar ni el vómito, ni la diarrea, un ejemplo. Es muy engorroso empezar una guardia y que te digan: No, solamente puedes hacer en una guardia de 24 horas cinco placas, o sea cinco rayos X de tórax. Porque solo hay cinco.

Mariana: Durante décadas, los médicos cubanos y el sistema de salud fueron considerados como uno de los mejores de la región. Esto creo que todos lo hemos escuchado. Era uno de los grandes pilares del modelo cubano y se podría decir que era como uno de los grandes orgullos para el país. Pero la crisis económica sostenida terminó por arrasar con esto y la situación ahora es tan precaria que si te vas a operar, tienes que tú como paciente llevar todo desde las agujas hasta el algodón.

Angel: Hay mucha carencia. Mucha no, la carencia es lo que rige un hospital hoy en día.

Mariana: Y esto, esta situación tan precaria en el sistema de salud, es generalizada. En el país, por ejemplo, las farmacias están vacías. Es muy difícil encontrar medicinas. Y para encontrar algo tan sencillo como un paracetamol, a veces tienes que ir al mercado negro. En el mercado negro las medicinas llegan desde el extranjero, o se las roban directamente desde los hospitales y las revenden. Pero cuando digo mercado negro, no se vayan a imaginar un callejón secreto oscuro. Esto sucede en pleno centro de la ciudad.

Señora: Medicamento, medicamento.

Señora 2: Hay medicamento, medicamento.

Mariana: Al mediodía encuentras revendedores vendiendo de todo. Lo que pasa es que todo lo vas a encontrar a unos precios realmente altos.

Ángel: Cada día que iba pasando me iba convenciendo más de que ejercer aquí iba a ser muy complicado. Y además también está el tema económico. O sea, no es bien pagada la medicina, más todas esas carencias.

Eliezer: Si Ángel estuviese trabajando para el Estado, ¿no? ¿Cuánto ganaría como un médico recién graduado en este momento?

Mariana: Ángel me dijo que el sueldo de un recién graduado no llega a los 5.000 pesos por mes y esto son como 14 dólares.

Angel: No mucho, de hecho no me da ni para llenar el tanque de gasolina. Una llenada de el tanque de gasolina es más que mi salario de un mes.

Mariana: Una de las grandes frustraciones de Ángel es que, como mencionamos antes, los médicos no pueden trabajar en el sector privado.

Ángel: Incluso lo veo un poco injusto, ¿no? Tantos sectores del país ahora mismo están en un proceso de privatización. Todo el mundo puede hacer su negocio. Sin embargo, un médico de otra especialidad, de otra índole no puede hacerlo. Es porque sería, no sé, mellar un logro de la revolución o algo así. Lo veo un poco injusto, ¿no? Porque creo, creo y abogo por un cambio en ese sector. No es abandonar el sector público, sino poder hacerlo un poco mixto.

Mariana: Ahora Ángel es taxista y me dijo que gana alrededor de 150 dólares por mes. Casi todo lo que gana lo está ahorrando para poder irse del país. Y bueno, este deseo que tiene Ángel es muy normal. Hay una especie de fiebre colectiva por salir de la isla. Cuba ha vivido muchas olas migratorias. Esta no es la primera, pero según los expertos, esta podría ser la ola migratoria más grande que se ha visto en el país.

Mariana: Mientras espera para irse, Ángel me cuenta que pasa sus días manejando y pensando en lo mucho que le gustaría volver a pasar consulta.

Angel: Todos los días. Incluso me levanto un poco melancólico, ¿no? Incluso cuando estoy manejando, me como la cabeza: Pudiera estar en una consulta en vez de estar manejando. Entonces es el día a día, ¿no? Pero bueno, siempre pensando en un futuro que pueda ser mejor, ya sea en Cuba o fuera de Cuba. Y que sí, que puedo volverme a sentar a una consulta. Pero bueno, por el momento no está siendo posible y nada, a luchar por ese sueño.

Eliezer: Ya volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Eliezer: Ahora, con todo esto que nos cuentas y que cuenta Ángel con salarios tan bajos en el sector público, ¿el caso de él es representativo de lo que pasa en general en Cuba con otros trabajadores del Estado? O sea, ¿hay mucha gente que se quiere ir del Estado al sector privado?

Mariana: Sí, en Cuba hay cientos de médicos, profesores, ingenieros que han tenido que emigrar a otro sector buscando mejores salarios. A este fenómeno en Cuba se le conoce como la pirámide social invertida. Y es que la gente con más calificación son los que menos remuneración reciben

Pedro: Conclusión: las escuelas y los hospitales se han quedado cada vez con menos personal y te encuentras en los bares, en los restaurantes y de guía de turismo a profesionales como cirujanos, como psicólogos, etc.

Mariana: Este tema también me lo explicó Pedro, el guía turístico que conocimos al principio.

Pedro: Entonces eso genera también una dependencia alta hacia ese sector de los servicios que diseñan lógicamente sus negocios para el turista. Eso genera que cada vez haya menos opciones para los cubanos en sí. Entonces, sí se ha vuelto una Habana muy prostituida, con todo el respeto que merecen las prostitutas, pero me refiero al término de muy volcada hacia satisfacer al turista.

Silvia: Y en el caso de Pedro, ¿cómo llegó él a convertirse en guía turístico?

Mariana: ¡Wow! A mí la historia de Pedro me sorprendió y fue un giro en la trama que realmente yo no me estaba esperando. Bueno, Pedro es joven y hace unos años, en el 2020, él se estaba cuestionando un montón de cosas, mayormente sobre a dónde iba el país, ¿no? Ese año, en el 2020, Pedro fue a una manifestación y esa manifestación como que lo marcó. Al año siguiente, en el 2021 fue a otra.

Pedro: Me manifesté en La Habana Vieja, aquí mismo y fui detenido.

Mariana: Luego llegó el 11 de julio de 2021, el estallido social que les contaba antes. Ese día, él decidió salir y lo volvieron a detener.

Pedro: Ya ahí yo supuse que ya era mi fin. Pero al final me volvieron a soltar.

Mariana: Pedro me dijo que no entendía nada. Y hasta el día de hoy no, no está muy seguro de la razón por la cual lo soltaron.

Pedro: Y bueno, ya en ese momento a mí no me interesaba seguir en la universidad. Para mí era mucho más grave lo que estaba pasando en Cuba y ya yo estaba tan psicológicamente molesto que yo dije bueno, mira, me voy.

Mariana: Él continuó dando clases de ciencias a niños en algunas escuelas. Eso fue así hasta que la seguridad del Estado, la policía política se acercó y pidió que en esa escuela no lo contrataran más.

Pedro: Me llegué a unas instancias del Ministerio de Educación donde conocía una persona y esa persona me dijo: te voy a decir lo que sucedió, que vino la seguridad del Estado y dijo que a ti no te contratarán más porque tú estabas haciendo que los muchachos se volvieran opositores. Lo cual es totalmente falso, porque yo sabía desde el primer momento por la condición de ya estar tachado en Cuba como opositor de que yo podía estar tranquilamente vigilado en cuanto a que yo hago Y eso es lo que se basaron para justificar que no, que no me contrataran. Entonces, como me quedé sin trabajo, en ese momento, pues bueno, nada, unas amistades me propusieron, gente que tenían casas de renta y tal, me dijeron: no quieres ponerte a trabajar como guía de turismo. Y ahí fue como comencé.

Y me ha permitido conocer una realidad que ya yo conocía, pero como transeúnte cotidiano, ¿entiendes? Ahora la he podido vivir como guía porque veo de cerca ese fenómeno.

Eliezer: ¿A qué fenómeno se refiere?

Mariana: Él se refiere a la cantidad de personas que hay pidiendo casi con desespero, dinero a los turistas. Y esto se ve sobre todo en La Habana Vieja por ser uno de los lugares más turísticos de la ciudad.

Pedro: Antes yo veía a la gente pidiendo dinero, lo veía de lejos. Ahora los veo delante de mí y veo su interacción. Y ha sido muy interesante que vayan conmigo por la calle y que mucha gente me grite en la calle: oye, dile la verdad, dile la verdad. Y mucha gente me dice: ¿por qué esa gente? ¿Por qué te dicen que digas la verdad? Yo le digo bueno, ya quieres terminar el tour y te empiezo a hablar de lo que ellos se refieren. Ok, le pusimos pausa. Olvídate de los edificios. Mira, vamos para allá. Y si no me crees, vamos a preguntarle a la gente.

En los tours se me han echado a llorar, sobre todo personas mayores. Esto le pasó a una persona mayor que de pronto venía con una idea y cuando empezó a ver con sus propios ojos me dijo: Por favor, no me cuentes más porque me has destruido ahora mismo el mito. Y le dije: señora, pero bueno. O sea, no estoy molesta contigo solamente, es que ya no puedo más, porque verdaderamente se me ha caído un mito. Y eso le pasa a muchas personas y a veces yo no sé si dejarlos vivir en su burbuja, ¿me entiendes? Y tengo mucha compasión con las personas mayores. Porque digo mira: Muérete con el mito. ¿Entiendes? Y ya no quieras ver lo que está sucediendo ahora, que es muy feo.

Mariana: Hay algo que me parece importante mencionar, y es que si bien Pedro gana más dinero ahora como guía que cuando era profesor, esto ha sido una experiencia complicada para él.

Pedro: Te digo que ha sido un choque de emociones fuerte. Es verdad que mi economía ha mejorado un poco, pero a costa de estar viendo una serie de cosas muy fuertes y es como un trabajo que te genera un poco, por lo menos a mi, disonancia cognitiva. O sea, es como que ya estoy ganando dinero, pero estoy viendo el desastre. O sea, y lo que he tratado un poco para estar un poco más tranquilo con mi conciencia es ser lo más ético posible respecto a eso, ¿entiendes? Y tratar de conducir el turismo por los lugares de los cubanos. ¿Entiendes? No llevarlos a los hoteles, no llevarlos a los grandes restaurantes, sino a los lugares pequeñitos de los negocios para que no vaya directamente a las arcas del Estado.

Silvia: Si todo es tan complicado como describe Pedro, ¿por qué no se va de Cuba como tantos otros?

Mariana: Realmente no quiere.

Pedro: ¿Para qué darle tantas vueltas al asunto? Me quedo porque siento que si la gente se sigue yendo, esto no se va a solucionar nunca. Me quedo porque no me da la gana de que esto se quede así impunemente. Me quedo por compromiso con los que están presos, con algunas amistades, las que he podido ayudar. No he podido ayudar a miles de presos políticos porque yo no soy Santa Claus. Con lo poco que he podido es compromiso de esperar a que ellos se salgan.

Mariana: Hay gente que le dice que tiene el síndrome del sobreviviente, una especie de culpa por haber zafado de la cárcel mientras que sus amigos siguen allí.

Pedro: Ahora yo lo asumo, digo ok, chévere me lo explicaste. No es ninguna patología ni nada, simplemente yo me siento así y lo confieso, no me voy porque creo que la gente que está presa ahora mismo no corrieron la misma suerte y necesitan también del apoyo de los que se quedan. Es verdad que afuera puedo ayudarlos más mandándoles dinero, pero yo considero que el cambio se produce en gran medida adentro.

Mariana: Este episodio fue producido y reportado por mí, Mariana Zúñiga, con el apoyo y reportería de Eileen Sosin. Lo editaron Silvia, Eliezer y Daniel Alarcón. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido es de Elías González, con música compuesta por él y por Remy Lozano.

Queremos agradecer a María Lucía Expósito, Elaine Acosta, José Jasan Nieves, Mario Luis Reyes y la FLIP – La Fundación para la Libertad de Prensa – por su ayuda en este episodio.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Nausica Palomeque Bruno Scelza, Desirée Yépez, Samantha Proaño, Natalia Ramírez, Juan David Naranjo Navarro, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Mariana Zúñiga: Throughout Latin America, you see inequality, right? But here the phenomenon seems more recent. And the differences seem to be getting bigger every day.

Eliezer Budasoff: In February of this year, our producer Mariana Zúñiga traveled to Cuba.

Mariana: It’s a place with many contrasts. Many of them are shocking. For example, I saw many old Soviet cars on the street. And suddenly you see two or three new SUVs. An example that perfectly portrays the contrast lived in Cuba was shown to me by Pedro, the tour guide with whom I took a tour of Old Havana.

Silvia Viñas: Well, Pedro is not his real name. We changed it to protect his identity.

Mariana: We were walking and we ran into a bodega.

Pedro: Do you already know what this is? What bodegas are? Have you already seen them? They’re these state-run places where supplies come every month and in a notebook where people are listed, they’re given a fixed amount, and well, it’s hardly enough, but it’s like something that alleviates the situation a bit.

Eliezer: Because they sell cheaper than what’s found in the market. The thing is everything is rationed.

Pedro: And well, it’s like a small respite, but the truth is, it’s a very short respite.

Mariana: This bodega was empty, dark, and barely had a couple of products on the shelves. If I remember correctly, they were floor cleaning soap bottles. And then on the right, on the other side of the sidewalk, there was a private market, which in Cuba is known as pymes.

Silvia: It’s likely that in your country they also use this term: pymes, to refer to small and medium enterprises.

Pedro: So, in contrast, there’s this. This is a pyme, you see? Notice it has many more products and they’re the ones that import.

Mariana: The store was clean, well-lit, and much better stocked. It had eggs, pasta, bag chips, hair cream, and other personal care products.

Pedro: When things like these pymes emerge, the contrast is very strong and have almost generated a contradiction in the city, and it’s the following: If pymes didn’t exist, then certain products wouldn’t exist. So they say: no, pymes generate inequality. But the issue is that, if they didn’t exist right now, we would be even more undersupplied.

But it’s not that the pyme generates more inequality, it just becomes more evident. The inequality already exists.

Eliezer: Welcome to El hilo, a Radio Ambulante Studios podcast. I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: And I’m Silvia Viñas.

While the bodegas offering subsidized food empty out, on the island private stores and businesses multiply, offering products and services that the State can no longer provide, but only for those who can pay for them.

Today, Cuba is going through what some experts already consider the worst economic crisis in its history, the most serious since the 90s, and for those living on the island, it’s about more than scarcity, which has always existed. Now, the situation seems aggravated by a phenomenon that has worsened in recent years: inequality.

It’s April 25, 2025

Eliezer: Mariana, was this your first time in Cuba? What was your first impression?

Mariana: Yes, this was my first time in Cuba. I was there for seven days, and my first impression was that everyone talks about “how bad things are”. Every day, all the time, and everywhere. “The thing” is like this omnipresent thing, redundancy aside, that’s everywhere.

In transportation, in markets, on the street, in church. It’s really difficult to escape the topic. And the crisis itself, because it’s everywhere. There’s a chronic food shortage. Salaries are very low. People say everything is extremely expensive.

Silvia: When we closed this episode, the price of a 30-egg carton was up to 2,500 pesos. A kilo of rice was 750 pesos, and a chicken package was 1,560 pesos.

Eliezer: To understand what these prices mean for most Cubans, you have to consider that the minimum wage has been fixed at 2,100 pesos monthly since 2020, which is more or less 6 dollars. So, it only covers the chicken package, or a kilo of rice. Both things are not possible. And for the egg carton, it doesn’t even come close.

Mariana: There’s not enough gasoline. Hospitals also lack sufficient supplies. And the electrical crisis is serious. In some places, power outages are daily and can last hours.

Silvia: Last March, there was a nationwide blackout. And the country was completely in darkness. It was the fourth time in six months that this happened.

Mariana: Cuba has been in crisis for a long time, but right now there seems to be a consensus that this crisis is worse than the one experienced during the Special Period. I talked about this with several people, and almost everyone said the same thing. When I talk about the Special Period, I’m referring to the early 90s, when the socialist bloc disappeared and the Soviet Union fell. At that moment, Cuba was severely affected economically because for years the Soviet Union gave Cuba a lot of aid, and this kept the Cuban economy afloat. But once the Soviet Union fell, all this aid disappeared. The shortage was brutal, and the people who lived through it described it with such horror that it seemed difficult to me that this crisis could be worse. So I went to talk about this with Juan Carlos Albizu Campos. He’s an economist and demographer.

Mariana: Hello

Juan Carlos: Did you arrive okay?

Mariana: Yes

Juan Carlos: That’s good.

Mariana: We went to his house, and I specifically remember that when we arrived, there was no electricity.

Juan Carlos: We’re without electricity.

Mariana: I imagine you’ve been asked this question a lot, but well, would you say this crisis is better, worse, or comparable to the Special Period?

Juan Carlos: As I see it, this crisis is much worse.

Mariana: Juan Carlos told me, and I more or less understood it this way, that this situation is the result of several crises together.

Juan Carlos: It’s not a classic crisis, it’s what is called a polycrisis model. Because it’s built on crises that were already being dragged along. First, the economic crisis produced by confinement and the closure, the virtual closure of the tourism sector. And all of that mounted on the effects of the international financial crisis that began in 2008, and which in Cuba provoked a financial crisis. That’s why it’s a cascade, a crisis mounted on another, which was not the case in the Special Period.

Mariana: Juan Carlos also told me that now the situation is more complex because at that time Cuba had things that no longer exist today.

Juan Carlos: Many industries, many productive processes that have disappeared, which wasn’t the case back then. So there were investment options and development options that don’t exist today.

Mariana: He also told me that at that time the crisis was really specific.

Juan Carlos: The crisis, truly the critical phase lasted 91, 92, 93, and 94. Then the recovery began.

Mariana: While now the crisis has been very long. Besides, back then the country wasn’t as indebted as it is now. And the other big difference is that today stores in Cuba are not completely empty as they were at that time.

Juan Carlos: What existed then was a crisis of scarcity, a very strong supply crisis. That’s the other issue. In this case, an emerging private sector has been interwoven, which didn’t exist in the Special Period. This sector has come to supplant the State in areas where the State has withdrawn.

Mariana: So, all this situation has ended up causing, or making more evident, the inequality in the country.

Silvia: Right, before, during the Special Period, there wasn’t so much inequality.

Mariana: At least at that moment everyone could access the same things. So, that made society seem more egalitarian.

I wanted to understand a bit more about the role of private enterprise in Cuba. So I spoke with this man named Oscar.

Oscar: My name is Oscar Fernández. I’m an economist, and to cut a long story short, during the pandemic I started this venture that has become a company, a small business, which turned out to be the first Cuban company to export dehydrated fruits.

Mariana: And he told me that now Cuba is experiencing a unique moment.

Oscar: If you travel to the past and go four or five years back and tell Cubans: look, I’m coming from 2025 and in 2025 you’ll have 11,000 registered private companies, these companies will import billions of dollars, some of them even from the United States. Nobody would have believed you because it was something that: this will never happen in this country. And it happened.

Silvia: Of course, because when you think of Cuba as a communist country, you don’t imagine many private companies. But are there other reasons why Oscar saw it as so distant, or impossible, that Cuba would have thousands of private companies?

Mariana: Yes, with private enterprise it’s the same as with other economic topics. When it seems things are moving forward, they slam on the brakes and go backwards.

Oscar: There has always been the government’s conception that the private sector is a bad thing. Sometimes it has been understood as a necessary evil. Sometimes they’ve had the intention of completely sweeping it away.

Mariana: This has happened many times before. It happened in the 90s, during the Special Period. At that time, they allowed many people to work independently. Professions like shoe shiners or manicurists, for example. And then, when there was an economic recovery, they backtracked. The same thing happened during Raúl Castro’s era. The list of activities that could be done privately expanded, and then, again, they stepped back. Until 2021 arrived.

Oscar: The pandemic changes everything everywhere in the world. Here there’s a situation that somehow channeled into massive protests on July 11th.

Audio archive, July 11 protests

Protesters: Freedom, freedom, freedom…

Mariana: People take to the streets. They take to the streets to protest, in a way that hadn’t happened in years, decades. And at that moment, Oscar says the government was forced to make a decision.

Oscar: So, one of the things they did was first authorize the creation of small businesses for the first time. That’s historic in Cuba, and second, they changed the list so that now, instead of having a list of permitted activities, the government issued a list of prohibited activities.

Eliezer: What does Oscar mean by prohibited activities? What are they?

Mariana: Everything related to media and journalism. Everything related to health and education. Things like mining, sugar and tobacco production. Some cultural activities, like book publishing. Sports activities. Everything related to science and research. Those kinds of things are prohibited, which means everything else can be done.

Eliezer: Now, you were telling us that in periods of crisis, the State usually turns to private entrepreneurs or private businesses to handle things they can’t do, right? This is happening right now, and that’s why Oscar can have his business. But what happened, why can’t the State handle these things anymore, like bringing in food, for example?

Mariana: Well, simply because they don’t have money. And they don’t have money for multiple reasons. But one of them is that the pandemic paralyzed tourism on the island, and the country never recovered.

Silvia: And why didn’t tourism recover?

Mariana: I think it’s because of the same crisis being experienced. Power outages and shortages. Cuba is not such an attractive tourist destination. I mean, going somewhere and there’s no electricity. Or going to the buffet in the morning and asking for an egg and they can’t give it to you. These are things that make people hesitate before going. Additionally, in Donald Trump’s first government, they put the country on a list of state sponsors of terrorism, which makes other countries, in Europe for example, hesitate to go to Cuba because they’ll then have problems with their visa to go to the United States.

Oscar: The government ran out of dollars. Because the hotels aren’t profitable and tourism is closed. Because sanctions increased, because they’ve let industries fail due to poor investment management, for whatever reason.

Mariana: So the State no longer has enough money to bring in food. Like bread, for example.

Oscar: Now a bread that used to cost 10 pesos costs 100. What actually happened is that the government withdrew the exchange rate subsidy it had for flour.

Mariana: Okay, what Oscar just said is worth explaining. In Cuba, flour is not produced. It has to be imported, but there’s no money to import that flour. So, private businesses – the pymes – are the ones importing flour and making bread. But because Cuba has exchange controls, it costs private businesses more money to buy flour. Why? Because they can’t buy dollars at the official price. So they have to go to the informal market where dollars are much more expensive. The consequence of this explanation, which can sound a bit convoluted, is that: Bread prices go up.

Oscar: So what happens? The salary of this worker is still old-fashioned, still set for the 10-pesos bread. Of course, it doesn’t cover the 100-pesos bread.

Silvia: Well, I imagine bread isn’t the only thing that’s now more expensive, right? How have price increases affected people?

Mariana: Well, many people simply go hungry, don’t eat enough, or eat less. And second, people start blaming private businesses for high prices.

Oscar: Population’s interpretation: Damn, the private businesses are abusing us. They’re getting rich off this.

Mariana: And the government, neither slow nor lazy, takes advantage of this narrative so they won’t be blamed. And well, if you take a look at the national press, you will find many articles that demonize the private sector, saying they don’t pay taxes, blaming them for inflation.

The reality is that if prices go up, the responsible isn’t the pyme owner. The responsible is all the economic distortion that exists and has existed, and the economic decisions the government has taken for too long.

Eliezer: Mariana, besides demonizing them in the press and public discourse, you were telling us this had happened before, right? Now the State is also somehow breaking private business activity.

Mariana: A bit, yes. For example, last year there were people who had licenses to sell as a wholesaler, and from one day to the next they woke up and no longer had the license. The little paper they had was no longer valid. This is the type of uncertainty those who now manage these businesses live with. For them, there’s always the possibility that the government will backtrack again and the private sector will lose the ground it has gained in recent years.

Silvia: Of course, but, I mean, the pymes survive because there are people who can buy. Who are these people who can pay these extremely high prices?

Mariana: Basically, they’re people who work in the private sector or people who receive remittances from a family member who emigrated.

Leonel: Mainly the clients are Cubans who emigrated, for economic, political reasons, or whatever, but maintain a strong emotional connection with family and friends here in Cuba.

Mariana: In Havana, I had the opportunity to meet Leonel, who owns an online market. An online store called Isla 360, which imports products from the United States, Spain, or Mexico.

Leonel: It initially started as a gift store. What happened is that the crisis after the pandemic was purely about food. So the public increasingly asked us for more, and right now we’re very specialized in food and personal care.

Mariana: When you go into the website, there are products like: ramen-style soups, bath gel, mint tea, strawberry jam, deodorants. But there are also basic products, the kind people used to find in the bodega and that now are scarce.

Eliezer: Perhaps the most powerful symbol of the depth of the crisis are the imports. Cuba used to be the world’s largest sugar exporter. Now it imports sugar. It also imports coffee, pork, and grains.

Leonel: And products that historically there was no need to import because there was really an internal production that covered that. We’ve had to import them. We never thought we’d see egg imports, for example. We never thought water would be imported. We never thought salt would be imported. We’re surrounded by salt.

Silvia: It’s estimated that more than 70% of the food consumed in Cuba comes from outside.

Eliezer: After the break, we’ll go to the countryside to understand why farming is so complicated in Cuba.

Silvia: We’re back in El hilo. We wanted to see how the economic crisis was affecting Cubans who produce food on the island. Mariana traveled almost three hours from Havana to Pinar del Río to meet one of them.

Mariana: During the trip, I was struck by how few cars were on the road.

Driver: They’re generally collective transports.

Mariana: And our driver, who is used to taking this route, told me this was normal.

Driver: Because of the gasoline issue. When you leave Havana, there’s almost no gasoline anywhere.

Mariana: And did you have to wait in a long line to fill your tank this time?

Driver: Yes, those are hours. You spend two, three, four hours, an entire day in one of those lines.

Mariana: We made this trip to see Isabel and her uncle Miguel. These are not their real names. We changed them for security as well.

Mariana: We were on the road for about three hours. And when we arrived, or when we thought we’d arrived, we actually had to get into a tractor because our car was too low and the road was terrible.

Miguel: You needed a car with more power, you see? Because the road is awful. It rained a lot this year and it couldn’t be fixed due to economic problems.

Mariana: On that journey, Isabel, Miguel’s niece, told us how things have been changing.

Isabel: This used to be all sugarcane. Sugarcane crops that of course you can see are no longer…

Mariana: For how long sugarcane has not been cultivated around here?

Isabel: More than 10 years.

Eliezer: What is Miguel’s farm like? What do they grow?

Mariana: Well, this is a large farm. It has a view of the sea, and here they grow things like papaya, tomatoes, garlic, yuca, guavas.

But especially mangoes. The farm is full of mango trees.

Mariana: Miguel is a 63-year-old man. His family describes him as a dreamer, which could be said to be rare because life in the countryside is very complicated. First, he has irrigation problems. The irrigation on his farm is electric. So when the power goes out, obviously he can’t, and when it comes back, sometimes there isn’t even enough voltage for the equipment to work.

Miguel: And sometimes this gives us a big impact on production because they’re small plants that do need irrigation. Frijol [beans], maíz [corn], frutabomba [papaya]. Those plants suffer a lot. Tomate [tomatoes], boniato [sweet potatoes] that need permanent irrigation. And in this time of year when there is more drought is when the lack of irrigation is most noticeable.

Mariana: Second, the country doesn’t have enough money to buy chemical fertilizers, which are the products needed to produce. There’s also no money to buy materials like, for example, files to sharpen machetes.

Miguel: We look for alternative methods, we mount stones on electric motors to sharpen machetes. A file is costing over a thousand pesos, and they’re not even high-quality files.

Mariana: But I think perhaps the most complicated or biggest problem they have is the lack of gasoline.

Miguel: We have to transport and sell all our production over long distances. We produce around 600 tons, almost all of which have to be transported more than 70 or 80 kilometers to feed the people. So what happens? When we don’t have the necessary fuel and transportation to sell it, well, then it passes. And that fruit is lost. It’s happened to us, we’ve lost hundreds of quintals.

Mariana: The lack of gasoline also means the product arrives in cities at a very high price because it passes through many hands and increases in price along the way.

Miguel: I sell tomatoes here at 20 pesos, and then it reaches Havana at 80 pesos. Look at the difference between 20 and 80.

And something very important in the countryside, where there isn’t so much production and so on, is the lack of salary. Because in the countryside, if there’s no production, there’s no salary. So, with that imbalance, there’s no motivation to work in the countryside.

Silvia: So what does Miguel think can be done? What would be the solution?

Mariana: For Miguel, the government must find a way, he doesn’t know which, to incentivize production in the countryside.

Miguel: This is the only way to keep the Cuban people alive, to produce food, to ensure food on the Cuban table. Because we can’t keep thinking about boats, about exports, because the country doesn’t have enough money to buy them. The food exists, but the country doesn’t have the conditions.

Mariana: But, unfortunately, betting on agriculture doesn’t seem to be something in the government’s plans. The government continues to bet on tourism and activities around this. Last year, the country invested 4.6 times more in hotel construction than in other sectors, like agriculture. And this is one of the great unknowns for Cubans. Why does the Government continue to bet on a sector in decline while people have nothing to eat? Well, nobody really knows the answer.

Eliezer: Of course, but what is the government doing to reactivate the economy? Is it really doing anything about the economic crisis other than building hotels and setting limits?

Mariana: It seems not. Somehow, there are certain things they want to pursue to capture more foreign currency. One of them is dollarization. They are trying, in some way, to gradually dollarize the country, and one of those ways has been by creating stores where people can go and only pay in dollars. That’s like a way to capture the money or dollars they aren’t receiving, right?

But economists say, well, they don’t believe this will have much much effect. In fact, Juan Carlos, the economist I spoke with and whom we heard at the beginning, is someone who thinks the problem is simply the model. He describes it as a dysfunctional model, one that isn’t even reformable. He compares it to a person in a terminal state, bedridden. Like those patients that doctors wonder how they’re still surviving, but nobody knows. And that there will come a moment when they can’t survive anymore. But he couldn’t tell me how long the patient would last.

Silvia: You were telling us that people who can buy products that have risen so much in price usually have their own business or receive remittances. But we wonder, what happens to the others? For example, people who work for the State and whose only economic income is their salary.

Mariana: The others are really struggling. Every day, the differences between those who have and those who don’t are becoming more notorious. During my visit, I met Claudia. She is a biologist and, since she is a scientist, she works for a state institution.

Claudia: Here, scientists are not well compensated at all. The salary is low. My salary is 5,000 something, almost 6,000.

Mariana: That’s around 17 dollars a month, more or less.

Claudia: That’s nothing. And I’m an auxiliary researcher.

Mariana: Neither her salary nor her husband’s, who is also a scientist, is enough to survive. But Claudia, like many other Cubans, lives with family. She lives with her in-laws.

Claudia: I’m lucky to be in a family where we all help each other and everyone’s salary goes towards the house, and that’s how we survive.

Mariana: Moreover, in her house, there are not just four mouths eating. There are six.

Mariana: Claudia is also a mother, she has twins, or “jimaguas”, as they say it in Cuba.

Claudia: They are little earthquakes. They’ll turn four now, but they’re quite sharp, they’re naughty, and it’s very funny because they’re very different from each other.

Silvia: Being a mother always comes with challenges, but I’m thinking about Claudia, about the situation she’s going through in Cuba. Did she tell you anything about what it’s like to be a mother in this situation?

Mariana: There’s physical, economic, and emotional exhaustion. And also, according to what Claudia told me, there’s a kind of guilt.

Claudia: Oh, it’s a very complicated feeling. I have many internal contradictions regarding motherhood because I don’t know if it’s because they were “jimaguas”, but it has been difficult. I’ve said: Oh, almost regretful of being a mother, and then I blame myself for feeling that, and then I adore them. They are my beloved torments.

Claudia: It’s difficult. It’s a complete challenge, first because the salary is not enough. Being parents is a responsibility because those children depend on you. It’s our responsibility that they eat well, and it’s complicated to maintain a balanced diet. And no, it’s not guaranteed in the basic food basket, in the “bodega”, as we say here. More and more products are disappearing, so more has to be found outside in the market to ensure that balanced diet. The milk itself, today I went to look for it, but it had been a long time since milk had been available.

Mariana: The situation is likely to worsen because in December, the government announced that this year subsidies for the basic food basket will be progressively eliminated. That is, the supply booklet will cease to exist. And while many products had already disappeared, people fear that the elimination of the booklet will further deepen the existing inequalities, right?

Claudia: Everything is a problem regarding the food preparation. Here we have a rice cooker. We have the “olla reina”, as we call it, which is electric. But if there’s no electricity, then we have to resort to gas. But gas has also become a problem because we’ve run out of gas cylinders. There’s no way to get them. So we’ve even had to cook with charcoal.

Mariana: For Claudia, it’s very important that her children eat protein, for example, every day. So they got a couple of laying hens that now live in their garden.

Claudia: And so the first hen arrived. Then another. Now we’re up to four and truly they help. In two or three days, we already have about six eggs. Yes, yes, the hens help a lot. The little hens of golden eggs.

Claudia: What I’m doing is trying to move forward. To solve, to see by what means and well… We try not to make everything about this problem. Yes, we vent, we talk about it, but well, that’s it. And the children, I think that’s the fundamental thing, because they are the center of our life, of our home. So we put everything around them. They are very funny, they are children, they are noisy. But, I mean, they fill you up, right?

Eliezer: Mariana, despite all this, the low salary and all the difficulties Claudia has, you haven’t told us if she has plans to leave her work in the state sector, right?

Mariana: No. Claudia has no intentions, for the moment, of leaving her job. Because despite everything, I think being a biologist makes her feel fulfilled. But I did meet someone who did it. His name is Ángel.

Angel: A 25-year-old, graduated in medicine. Currently disconnected from that work life. Well, I make a living working as a taxi driver.

Silvia: Before making this decision, what was his life like as a medical student?

Mariana: He was happy. He liked his life as a student, as a doctor seeing patients, but it was full of frustrations. And he would get frustrated when patients came to the hospital and he had no supplies to offer them.

Angel: I have anecdotes of patients who have arrived at my consultation with vomits and diarrhea. Dehydrated, and the only thing I have is a serum to give them, I can’t stop neither the vomiting nor the diarrhea, for example. It’s very cumbersome to start a shift and be told: No, in a 24-hour shift you can only do five chest X-rays. Because there are only five.

Mariana: For decades, Cuban doctors and the healthcare system were considered one of the best in the region. I think we’ve all heard this. It was one of the great pillars of the Cuban model and could be said to be one of the country’s great sources of pride. But the sustained economic crisis ended up devastating this, and the situation now is so precarious that if you’re going to have surgery, you as a patient have to bring everything from needles to cotton.

Angel: There’s a lot of shortage. A lot? No, shortage is what governs a hospital today.

Mariana: And this, this precarious situation in the healthcare system, is widespread. In the country, for example, pharmacies are empty. It’s very difficult to find medicines. And to find something as simple as paracetamol, sometimes you have to go to the black market. In the black market, medicines arrive from abroad, or are directly stolen from hospitals and resold. But when I say black market, don’t imagine a dark secret alley. This happens right in the city center. At noon, you find resellers selling everything. The thing is, you’ll find everything at really high prices.

Woman : Medication, medication.

Woman 2: There is medication, medication

Ángel: Each day that passed was convincing me more that practicing here was going to be very complicated. And also there’s the economic issue. I mean, doctors are not well paid, plus all those shortages.

Eliezer: If Ángel were working for the State, right? How much would he earn as a newly graduated doctor at this moment?

Mariana: Ángel told me that the salary of a newly graduated doctor doesn’t reach 5,000 pesos per month, which is like 14 dollars.

Angel: Not much, in fact, it doesn’t even cover filling up a gas tank. Filling up a gas tank costs more than my salary for a month.

Mariana: One of Ángel’s great frustrations is that, as we mentioned before, doctors cannot work in the private sector.

Ángel: I even see it as a bit unfair, right? So many sectors of the country are now in a privatization process. Everyone can do their business. However, a doctor of another specialty cannot do so. It’s because it would be, I don’t know, dulling a revolutionary achievement or something like that. I see it as a bit unfair, right? Because I believe, I believe and advocate for a change in that sector. Not abandoning the public sector, but being able to make it a bit mixed.

Mariana: Now Ángel is a taxi driver and told me he earns around 150 dollars per month. Almost everything he earns he’s saving to be able to leave the country. And well, this desire he has is very normal. There’s a kind of collective fever to leave the island. Cuba has experienced many migratory waves. This is not the first, but according to experts, this could be the largest migratory wave seen in the country.

Mariana: While waiting to leave, Ángel tells me he spends his days driving and thinking about how much he would like to return to the hospital.

Angel: Every day. I even wake up a bit melancholic, right? Even when I’m driving, I torture myself: I could be in a consultation instead of driving. So it’s the day-to-day, right? But well, I am always thinking about a future that might be better, either in Cuba or outside Cuba. And yes, that I can sit down at a consultation again. But well, for the moment it’s not being possible and well, fighting for that dream.

Eliezer: We’ll be right back.

Silvia: We’re back on El hilo.

Eliezer: Now, with everything you’re telling us and what Angel says about such low salaries in the public sector, is his case representative of what’s generally happening in Cuba with other state workers? I mean, are there a lot of people who want to leave the state sector for the private sector?

Mariana: Yes, in Cuba there are hundreds of doctors, teachers, engineers who have had to migrate to another sector seeking better salaries. This phenomenon in Cuba is known as the inverted social pyramid. And it’s that the most qualified people are the ones who receive the least remuneration.

Pedro: Conclusion, schools and hospitals have been left with less and less staff, and you find professionals like surgeons and psychologists working in bars, restaurants, and as tour guides.

Mariana: Pedro, the tour guide we met at the beginning, also explained this to me.

Pedro: So this also generates a high dependency on the service sector that logically designs their businesses for tourists. This generates fewer and fewer options for Cubans themselves. So it has become a very prostituted Havana, with all the respect that sex workers deserve, but I mean in the sense of being very focused on satisfying tourists.

Silvia: And in Pedro’s case, how did he become a tour guide?

Mariana: Wow! Pedro’s story surprised me and was a plot twist I really wasn’t expecting. Well, Pedro is young and a few years ago, in 2020, he was questioning many things, mostly about where the country was heading, right? That year, in 2020, Pedro went to a demonstration and that demonstration kind of marked him. The following year, in 2021, he went to another.

Pedro: I demonstrated in Old Havana, right here, and I was detained.

Mariana: Then came July 11, 2021, the social outbreak I was telling you about before. That day, he decided to go out and was detained again.

Pedro: By then I assumed it was my end. But in the end, they released me again.

Mariana: Pedro told me he didn’t understand anything. And to this day, he’s not very sure of the reason why they let him go.

Pedro: And well, at that moment I was no longer interested in continuing at the university. For me, what was happening in Cuba was much more serious, and I was so psychologically upset that I said well, I’m leaving.

Mariana: He continued teaching science to children in some schools. That was until state security, the political police, requested that he not be hired at that school anymore.