Cultura digital

Política

Big Tech

Natalia Viana

Amazon

Meta

Microsoft

Apple

Las empresas tecnológicas más importantes del mundo tienen una influencia enorme en la política de América Latina, y se han convertido en un desafío para los países que intentan ponerles límites. Entre 2024 y 2025, las Big Tech consiguieron debilitar una regulación que buscaba proteger la salud mental de los menores en Colombia y un proyecto de ley sobre noticias falsas en Brasil, que imponía mayor transparencia y responsabilidad para lo que se publica en las redes sociales. Esta semana conversamos con la periodista Natalia Viana, directora del medio brasileño Agência Pública, que lideró junto al Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP) la investigación regional La mano invisible de las Big Tech, para entender cómo operan estas empresas para cambiar voluntades, intervenir en procesos institucionales e instalar narrativas que favorecen a sus intereses.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Franklin Villavicencio -

Edición

Eliezer Budasoff, Silvia Viñas -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción digital

Samantha Proaño, Franklin Villavicencio, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Elías González -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

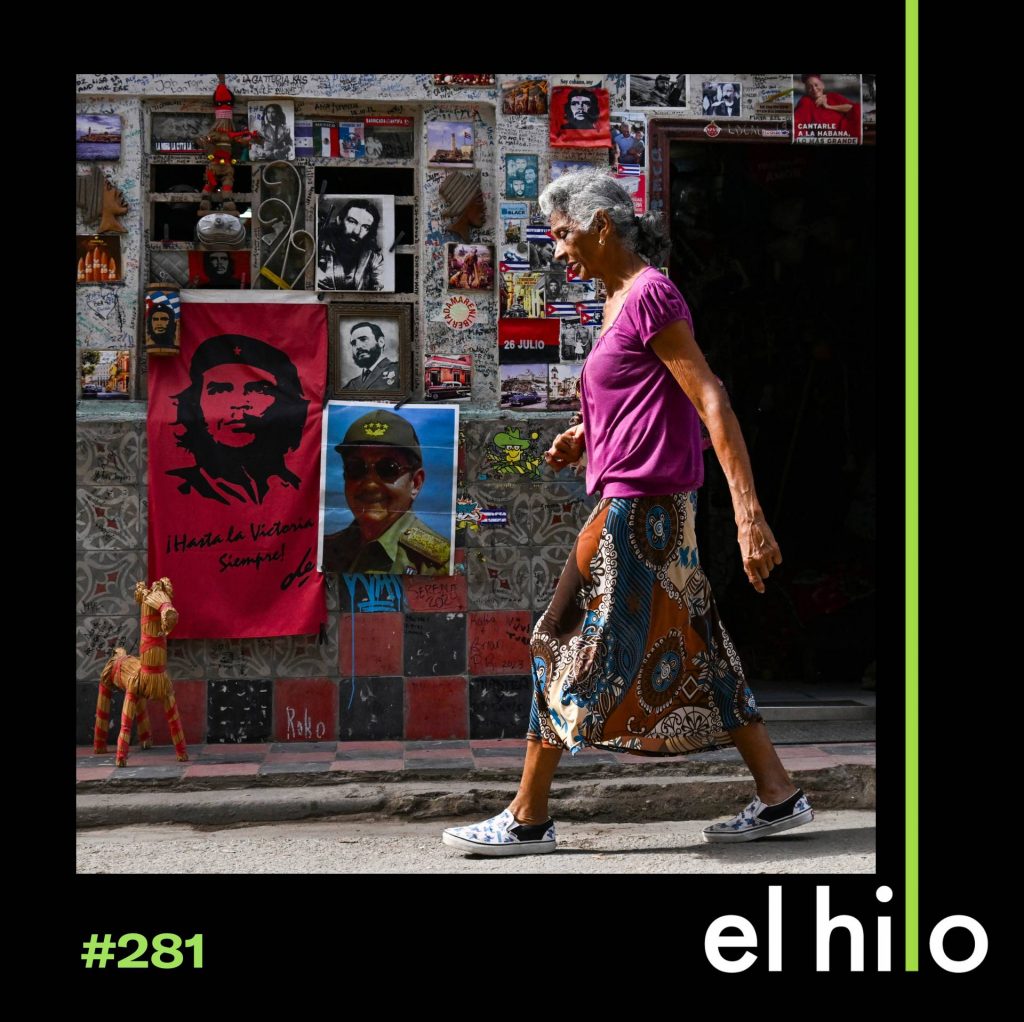

Fotografía

Getty Images / Matt Cardy

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Eliezer Budasoff: Antes de empezar, queremos recordarte que seguimos en campaña de donación hasta el 31 de diciembre, así que si no has tenido la oportunidad de apoyarnos, este es un gran momento. En El hilo creemos en el valor del buen periodismo, ese que profundiza, que da contexto, que busca explicar de manera clara lo que pasa en nuestra región. Pero ese periodismo es costoso y requiere mucho esfuerzo y cuidado. Si llevas tiempo escuchándonos y valoras el trabajo que hacemos, esta es el momento de apoyarnos.

Silvia Viñas: Además, esta semana logramos algo muy especial: gracias al esfuerzo de un grupo de donantes, podremos triplicar cada aporte que nos hagas hasta completar 20 mil dólares. Si, por ejemplo, nos donas 30, recibiremos 90. Entra a elhilo.audio/donar. No importa el tamaño de tu aporte. Todo cuenta. ¡Mil gracias! Y si ya lo hiciste, por favor, envíale este link a tus personas cercanas para que también nos apoyen. Recuerda: elhilo.audio/donar. ¡Gracias por apoyar el periodismo independiente!

Aquí el episodio.

Eliezer: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: Y yo soy Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: Entre finales de 2024 y mediados de 2025, en Colombia y en Brasil se frenaron dos regulaciones clave que ponían el foco en las redes sociales.

Audio de archivo, Congreso de Colombia: He presentado una proposición de eliminación a este artículo, pues raya con la censura.

Audio de archivo, noticiero de Brasil [en portugués]: El expresidente Michel Temer es contratado por Google para ayudar en la negociación de la regulación de las plataformas de internet.

Silvia: Estas dos iniciativas, un artículo y un proyecto de ley, buscaban reducir el impacto que las plataformas pueden tener en la salud mental de los menores o en la democracia. Cuesta pensar que alguien pueda oponerse a proteger cosas así, pero el intento de poner límites a los contenidos en línea afecta directamente los intereses de un puñado de empresas que se han vuelto un poder en sí mismo alrededor del mundo.

Eliezer: La forma en la que se frenaron estas regulaciones dejó en claro que en los dos países hubo acciones coordinadas para cambiar voluntades, intervenir en procesos institucionales o construir narrativas que favorecían a las grandes compañías tecnológicas. Una investigación multinacional liderada por el medio brasileño Agencia Pública y el Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística, el CLIP, ha hecho visibles algunas de estas estrategias, y el desafío que supone para nuestros países enfrentar un poder como el de las big tech.

Silvia: Hoy, cómo opera una red de lobby que busca influir en la política nacional y reducir las regulaciones a las grandes tecnológicas en América Latina.

Es 12 de diciembre de 2025.

Audio de archivo, Olga Lucía Velásquez: En el último debate en el Senado nos quitaron ese elemento que traía sanciones frente a contenidos que afectaban la salud mental, con el argumento de, pues, era ir en contra de la libre expresión.

Silvia: Están escuchando a la congresista colombiana Olga Lucía Velásquez durante una entrevista que le hicieron en junio de este año. Ella es una de las autoras de un proyecto de ley de salud mental, una de las regulaciones que mencionamos al comienzo de este episodio. Ese proyecto tenía un artículo, el número 8. Buscaba sancionar a las plataformas si incumplían códigos de conducta establecidos por la Comisión Reguladora de Comunicaciones de Colombia, la CRC.

Eliezer: Este artículo provocó el despliegue de una maquinaria de lobbistas de parte de las grandes tecnológicas, como Meta, cuyo fin era suavizar la regulación. De pronto, algunos legisladores empezaron a hablar en defensa de lo que llamaron “las múltiples partes interesadas en internet”.

Audio de archivo, Congreso de Colombia: Una cantidad de gremios que están solicitando que se elimine el artículo 8. ¿Por qué? Afectación a la libertad de expresión. La posibilidad de que un solo actor como la CRC intervenga en contenidos digitales podría derivar en decisiones que no tengan en cuenta las múltiples partes interesadas en Internet.

Silvia: La ley se considera un hito histórico en Colombia por su alcance en salud mental, y terminó siendo aprobada en su mayor parte. Pero en el camino sacrificó algo importante: proteger a niños, niñas y adolescentes de contenidos nocivos en plataformas digitales. En cambio, dejó en manos de las grandes compañías tecnológicas, las big tech, una función reguladora en la que, para los autores del proyecto, era necesaria la participación del Estado.

Eliezer: En Brasil pasó algo similar. Las big tech consiguieron frenar un proyecto de ley que buscaba regular a plataformas digitales como Facebook, Instagram y Google. Les exigía mayor responsabilidad y transparencia después del asalto a los Tres Poderes que llevaron adelante los seguidores del expresidente Jair Bolsonaro, que este año fue condenado a 27 años de cárcel por un complot golpista.

Audio de archivo, noticiero de Brasil [en portugués]: En una nota, Google asumió una manifestación pública sobre el proyecto de ley y dice que invirtieron en campañas de marketing para dar visibilidad a los puntos que la empresa entiende como preocupantes.

Silvia: Para entender cómo funciona esta operación de lobby y presión política, conversamos con Natalia Viana, periodista brasileña y cofundadora del medio Agência Pública. Ellas y el CLIP trabajaron juntos en una investigación transnacional y muy amplia sobre las big tech y su red de influencias.

Eliezer: Ustedes le llamaron “la mano invisible” y de alguna forma el trabajo que hacen ustedes es hacerla visible. Pero para empezar, ¿puedes contarnos un poco, primero, quiénes conforman este grupo de empresas multimillonarias?

Natalia Viana: Bueno, para empezar, ¿qué son las big tech? Big tech es un término un poco más amplio que… Habla de empresas que son únicas en la historia del capitalismo, que lograron obtener una rentabilidad y un lucro altísimo, y que también lograron controlar la gran parte de lo que es la economía digital. Entonces, hay cinco o seis grandes hermanas que se dice, que son Amazon, Meta de Facebook, Instagram y Whatsapp, Alphabet de Google, entre ellas está también Apple. Aquí en Latinoamérica tenemos Mercado Libre, que es gigante, así como Rappi.

Silvia: Pero también están otras que recientemente han entrado a esta categoría, como TikTok y OpenAI, que es la dueña de ChatGPT.

Natalia: Se habla mucho como se habla del big oil o big food, son las mayores de la industria tecnológica.

Eliezer: Recién mencionabas esto de que han logrado controlar o poseer la mayor parte de la economía digital. Eso que vos estás hablando de que nunca se había tenido esta magnitud de empresas dentro del capitalismo. ¿Cuál es el peso económico, social y político que tienen estas empresas en el mundo? Pero sobre todo en América Latina.

Natalia: Bueno, yo creo que hay algunas características de este sector económico que son únicas en la historia, pero ese es un factor. Hay otro factor que es la extrema concentración de los mercados, y eso sí, replica en todo el mundo y en cada país. Entonces, si tú miras, por ejemplo, el control del mercado de búsquedas, el control del mercado de chats, el control del mercado de redes sociales, el control del mercado de streamers, de podcasts, etcétera, etcétera, también son casi todos o un monopolio o un oligopolio. El control de Google sobre búsquedas, por ejemplo, es una locura. Es más del 80% en casi todos los países.

Audio de archivo, RTVE: Google es un monopolio, así lo ha sentenciado un tribunal federal de Washington. Asegura que el buscador controla el 90% de las búsquedas en Estados Unidos y que se ha dejado millones de dólares en contratos de exclusividad.

Natalia: En todos los países, estas empresas tienen el mismo poder. Y este poder, es el poder de determinar las conversaciones entre las personas.

Eliezer: Claro. Justo en los últimos años, pero sobre todo en los años recientes, hemos visto cómo alguna de las principales figuras, de los CEOs de estas empresas, tienen un papel relevante dentro de los círculos del poder político. La más clara es cómo lo hemos visto en la relación entre los CEOs y Donald Trump durante su nuevo gobierno. Desde ir a su toma de posesión hasta reunirse a cenar en la Casa Blanca.

Archivo de audio, Mark Zuckerberg [en inglés]: Gracias por invitarnos. Este es un grupo bastante grande y, quiero decir…

Archivo de audio, noticiero: Allí estaban Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates y Tim Cook, entre otros.

Archivo de audio, Sergey Brin [en inglés]: Y el hecho de que su administración está apoyando a nuestras compañías en lugar de pelear con nosotros.

Archivo de audio, noticiero: Esta cena es el ejemplo más reciente de un delicado cortejo bidireccional entre Trump y los líderes tecnológicos.

Archivo de audio, Donald Trump [en inglés]: Bill, ¿quieres decir unas palabras?

Archivo de audio, Bill Gates [en inglés]: Gracias por su increíble liderazgo. Quiero agradecer…

Eliezer: ¿Cuál es esta dinámica de las big tech con los gobiernos de América Latina? ¿Cómo se mueven en estas aguas?

Natalia: Hay actuaciones distintas en distintos países. En general, casi todas esas big tech no dan atención, no tienen oficinas, no tienen gente en los países. Entonces, de hecho, tratan a los latinoamericanos, incluso a los gobiernos latinoamericanos, como una segunda clase. Así que actúan de manera muy fuerte siempre que hay leyes que de hecho van contra sus intereses, pero actúan mucho por asociaciones transnacionales. Entonces, hay asociaciones como la ALAI, que es la Asociación Latinoamericana de Internet.

Silvia: Podríamos decir que la ALAI es una alianza clave de empresas tecnológicas que opera como una de las principales herramientas de lobby o influencia para estas corporaciones en la región. Natalia nos explicó que la ALAI actúa en varios países al mismo tiempo. Ellos dicen no representar los intereses de ninguna tecnológica, pero investigaciones como las que hizo CLIP, demuestran lo contrario.

Natalia: Entonces, si tú miras al tipo, el presidente, el representante de la ALAI, va a muchos congresos para actuar. En el caso de Brasil, es diferente, porque Brasil es uno de los mayores mercados de las big tech. Entonces, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, etc. Para Brasil hay toda una operación mucho más robusta.

Eliezer: Por ejemplo, en Brasil, un medio que participó en la investigación, Núcleo Jornalismo, identificó que Meta es la empresa con más profesionales en las áreas de políticas públicas o relaciones gubernamentales. Se identificaron entre 19 y 75 nombres en el país.

Natalia: Pero son 74 funcionarios de las big tech, además de escritorios de lobby, además de asociaciones, además de gente que son cooptados o que hablan sobre sus intereses, etc. Y este es un grupo muy grande. Eso en Brasil.

Silvia: Hay otros casos también, como México, donde funcionarios y lobbistas están abriendo puertas a las grandes tecnológicas para que puedan instalar centros de datos en el estado de Querétaro. Estos centros son enormes almacenes, que albergan miles de equipos funcionando día y noche y consumen millones de litros de agua a diario. Y está el caso de Chile, donde ya hay 49 de estos centros y hay planes para abrir más. Hace un par de semanas publicamos un episodio sobre esto.

Eliezer: Todo esto, además, en un contexto donde se mezcla con la geopolítica y los intereses no solo de estas grandes compañías, sino también de Estados Unidos.

Natalia: Para mí es un tema muy interesante que las tecnológicas hayan acercado tanto a Trump y que por otro lado, Trump esté utilizando la defensa de las empresas tecnológicas contra la regulación como uno de los principales ejes en negociación con todos los países del mundo, con amenazas.

Silvia: En septiembre, Trump anunció que va a aplicar aranceles y a restringir las exportaciones a cualquier país que regule a sus tecnológicas.

Natalia: Eso demuestra que esta es la mayor batalla mundial y que ellos están ahora dentro del gobierno, cerca del gobierno, para que se impida la regulación.

Eliezer: Hacemos una pausa y volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Eliezer: Muchas de las estrategias que utilizan estas empresas, cuando las mencionas, hacen acordar un poco a las que solían usar las tabacaleras, o las grandes empresas de bebidas alcohólicas, que mezclaban un poco esto del lobbismo, la compra de influencias, estudios o análisis no del todo objetivos. Pero de lo que cuentas y de lo que habla la investigación, pareciera que las big tech lo potencian, ¿no? Es como esto recargado. ¿Puedes explicarnos un poco en qué se diferencia de las dinámicas que han establecido otras industrias en el pasado?

Natalia: El simple hecho de que tienen mucha más plata, pero mucha, mucha plata. Como yo te conté, se vuelven el grupo más poderoso de lobby en muchos países, incluso en Estados Unidos y en Europa y también en nuestros países. Es un hecho, a decir, relevante por sí mismo. Pero las big tech pueden potencializar su poder de negociación porque hoy día los políticos necesitan de las big tech para elegirse. Entonces, por ejemplo, en Brasil, pero también en otros países, una manera de ser aliados o cercanos a los partidos es darles entrenamiento en sus herramientas, es dejar funcionarios para que atiendan a los políticos a cualquier hora del día o de la noche si tienen problemas. Entonces, si tú tienes problemas con tu Facebook, no vas a lograr nunca hablar con una persona de Facebook. Si eres un diputado, te aceptan, hablan contigo inmediatamente.

Silvia: Es decir, las redes se han convertido en un actor central en la política latinoamericana. No estar en ellas, ya sea durante la campaña o después, es como no existir en el tablero político.

Natalia: Y hay incluso una alianza política que están haciendo en Brasil, y lo hicieron muy fuerte con los políticos de la extrema derecha que llegaron al poder por el poder de las redes, por el Facebook, por ejemplo. Entonces, esta alianza se vuelve cada vez más cercana y cada vez más natural. Y después que ahora son aliados de Donald Trump, incluso, yo creo que dejaron, a decir, la neutralidad política que siempre tuvieron. Muchos congresistas tienen miedo a volverse un enemigo de ellos, porque hoy un político en Latinoamérica necesita de las plataformas para elegirse, para hablar con sus constituyentes, con sus votantes.

Archivo de audio, noticiero: El candidato derechista Jair Bolsonaro reconoció a través de una transmisión en vivo en Facebook, que las redes sociales tienen mucho que ver con su liderazgo en los sondeos presidenciales de Brasil.

Archivo de audio, noticiero: En Twitter, el derechista recordó nuevamente los lazos del partido de su rival con la corrupción.

Audio de archivo, Jair Bolsonaro [en portugués]: Yo pido, en esta recta final de las elecciones en Brasil, solo dos minutos de su atención.

Natalia: Por otro, las decisiones son muy concentradas en un grupo muy chico de ejecutivos en Silicon Valley. Entonces, la manera en que el lobby funciona es súper concentrado y por eso se replican en varias partes. Una de las características, por ejemplo, es la gratuidad. Los regalitos que dan. Porque todas esas empresas tienen, por ejemplo, unas reglas de compliance que no pueden pagar propina. Pero pueden dar, por ejemplo, llevar a almorzar o cenar o a happy hours. Y, por ejemplo, yo sé que en una de ellas, en Meta, pueden gastar 150 dólares en una cena con un parlamentario. En Brasil, 150 dólares es mucha plata para una cena. Pero como son decisiones tomadas en Estados Unidos, ahí está bien. Entonces, tienen mucho poder. Y cómo las decisiones son tomadas allá, hay cosas que en nuestras realidades son poderosísimas, como esta. Eso es sólo un ejemplo.

Eliezer: Una vez que esta maquinaria del lobby se pone en marcha, digamos, más allá de los casos puntuales que ahora vamos a hablar, ¿qué tipos de regulaciones suelen buscar frenar? ¿Y cuáles son los países de América Latina en los que se ha documentado esta influencia?

Natalia: Bueno, nosotros documentamos esa influencia en Colombia, en Argentina, en Chile, México y Ecuador. Y también, obviamente, Brasil. Hay un par de leyes, lo que se está intentando regular en el mundo y también en Latinoamérica. Primero, leyes que defienden los derechos de los niños.

Silvia: Por ejemplo, la que contábamos al principio, la de Colombia. Que buscaba ampliar la moderación sobre temas que pueden afectar a niños y adolescentes.

Natalia: Otra es la responsabilización sobre lo que es publicado, que es el tema de las fake news o de la desinformación. Si el contenido publicado es ilegal en el mundo, afuera de lo digital, que también sea en lo digital. Es lo que Brasil intentó hacer, por ejemplo. Otra cosa que se está intentando regular es la cuestión de competencia, como yo decía. Entonces, como tienen control de mercados enteros, hay que tener reglas. Si tienen ese control, entonces una parte hay que romperse o darse a un competidor nacional. Y hay también otro tema que es el tema de los impuestos, ¿no? Tienen que pagar impuestos, cuánto pagar, etcétera, etcétera. Eso es lo que está pasando en varias partes.

Eliezer: Vamos a detenernos un poquito en algunos de los casos que acabas de mencionar. El de Colombia, por ejemplo, que estuvo muy cerca de obligar a los gigantes tecnológicos a responder por los contenidos que afectan la salud física y mental de los niños, ¿no?, de los menores. Sin embargo, esto fue truncado por las big tech. ¿Cómo pasó?

Natalia: Esto, bueno, un poco con lo que yo decía, esas asociaciones transnacionales, también los propios lobbistas de las big tech fueron a presentar en el Congreso, presentar sus puntos, etcétera. Lograron muchas alianzas que les dieron mucho tiempo para defender sus visiones. Pero también ahí pasó una cosa, que pasó mucho en Brasil y que es quizá lo más violento de lo que están haciendo las big tech. Qe es asociar cualquier intento de regularlas y regularlas simplemente para mitigar el daño que causan a la sociedad con un intento de censura.

Y eso ellos lo hicieron en Colombia ─también lo hicieron en Brasil─, con una alianza con la extrema derecha. Y ahí, en las redes sociales mismas, esta narrativa de que intentar regular es censura, se crece y se vuelve casi que impide la discusión. También otra cosa que ellos hacen mucho y que pasó también en el caso colombiano, es que algunos de esos grupos internacionales, financian viajes donde los parlamentarios van a sus escritorios, a sus oficinas, a sus headquarters, y ahí pasan muy bien, reciben más regalitos, hablan con gente que son muy inteligentes y que saben todo de tecnología, que también es una manera de seducción. Y ahí nosotros mapeamos, la gente de CLIP específicamente, mapeó algunas de esas reuniones donde los intereses se mezclan mucho con lo que es pasarlo bien.

Eliezer: Hacemos una última pausa y volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta.

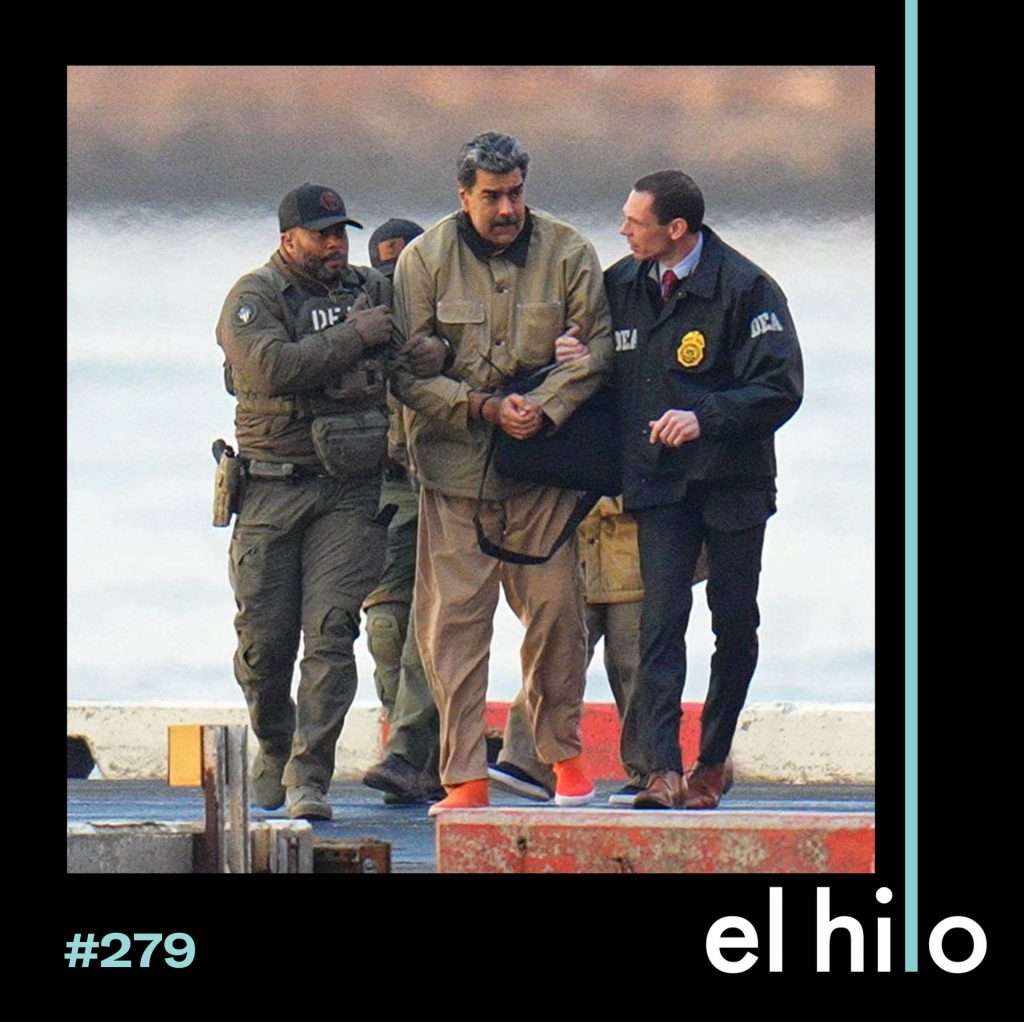

Eliezer: Tenemos el caso de Brasil, donde Google contrató al expresidente Michel Temer para hacer lobby por la llamada ley de fake news, algo que tú mencionabas hace un ratito. Y así han sido contratados otros perfiles desde la gestión pública hasta las agencias regulatorias. A esta dinámica ustedes las han llamado “puerta giratoria”. ¿Nos podrías explicar qué significa y cómo funciona?

Natalia: Bueno, la puerta giratoria nos pareció un tema súper importante, porque vuelvo a la investigación que hizo Núcleo Periodismo. En Brasil, fueron 74 funcionarios de las big tech que trabajan en los departamentos de Policy, Public Policy, o Global Affairs, o Public Affairs. Son gente que son contratadas para intentar modelar las leyes al interés de las big tech. No hay otra descripción de su trabajo que eso. Y son, por tanto, lobbistas. Esta gente trae, obvio, su conocimiento de cómo funciona la cosa pública, los gobiernos, pero más que eso, porque traen sus alianzas, sus amistades, su influencia, y facilitan la entrada, a decir, la infiltración, de los argumentos de las big tech adentro de los gobiernos. En Brasil, Michel Temer, que fue un presidente bien relevante, fue el presidente que asumió después del impeachment de Dilma Rousseff, fue contratado ya casi en el final de toda la estrategia de las big tech para matar la regulación que más cerca llegó, que era la ley de las fake news.

Archivo de audio, noticiero: El gobierno federal va a intentar una nueva aproximación con el Congreso para que el tema de la regulación de las plataformas digitales vuelva a la agenda de los legisladores. El proyecto de ley, también conocido como PL de las fake news, todavía está parado…

Natalia: Y Michel Temer tiene mucha influencia desde la Constituyente. Entonces, Michel Temer si llama a cualquier persona en el Congreso, lo van a recibir. Porque Michel Temer, que es abogado, tiene influencia en la Corte Suprema. Ustedes saben que la Corte Suprema de Brasil está de pelea con las big tech. Pero, una pelea violenta, porque están intentando, de hecho, responsabilizarlas, por lo que fue el intento de golpe de Estado de 2023.

Eliezer: Natalia se refiere al ataque a los Tres Poderes en Brasilia, en enero de 2023. El expresidente Bolsonaro fue condenado en septiembre de este año como el responsable de encabezar una conspiración para desacreditar el sistema electoral brasileño, atacar instituciones y desconocer el resultado de las elecciones que perdió contra Lula.

Silvia: Este intento de golpe de Estado llevó a que la Corte Suprema de Brasil tomara la decisión de declarar al artículo 19, del Marco Civil de la Internet, como inconstitucional. El artículo decía que las plataformas no son responsables de lo que subía la gente. Solo si un juez les ordenaba borrar algo ilegal y no lo hacían.

Archivo de audio, noticiero: La decisión afecta a empresas como X, TikTok, Instagram y Facebook, que en adelante deberán eliminar de inmediato publicaciones que promuevan acciones antidemocráticas, terrorismo, discursos de odio, pornografía infantil y otros crímenes.

Natalia: Entonces esos nombres muy altos, abren puertas, y claro, cobran mucho por eso, por supuesto. Otro ejemplo que, para mí, me parece súper relevante, es el ejemplo de Tony Blair. Tony Blair tiene su instituto, que es el Tony Blair Institute, en Inglaterra. Y el Tony Blair Institute, que antes trabajaba temas como desigualdad, terrorismo, etcétera, hace un par de años, empezó a trabajar la modernización del Estado, que ¿cómo se hace?, utilizando inteligencia artificial. ¿Qué descubrimos? Y eso, quien lo descubrió fue Lighthouse Report, que es una organización europea, que también fue miembro de esta investigación. El Tony Blair Institute recibió como cientos de millones de libras, del fundador de Oracle, Larry Ellison.

Silvia: Quizás Oracle no te suena en la carrera de la IA, porque no es tan común de escuchar como ChatGPT y otros chatbots. Pero es uno de los grandes en la industria. Sobre todo, se ha centrado en áreas como la medicina, servicios para gobiernos y servicios en la nube. También es la empresa propietaria del lenguaje de programación Java. En los últimos meses, Oracle asumió un rol de supervisor en el traslado de las operaciones de TikTok, de origen chino, a Estados Unidos. Oracle tendrá acceso al algoritmo de la red social.

Natalia: Y que, incluso, en algunos momentos que logramos obtener con documentos o con mucho cruzamiento de fuentes diversas, mientras están trabajando con gobiernos, es decir, necesitan adoptar inteligencia artificial para mejorar la gestión pública, etcétera, dicen “quizá la estrategia o quizá la herramienta de Oracle es la mejor que pueden utilizar”. Entonces, ahí es un lobby absolutamente disfrazado.

Eliezer: Viendo este panorama que tenemos en la región con políticas frágiles y sociedades desprotegidas, ¿a qué se enfrentan organizaciones civiles, usuarios y los estados frente a estas manos invisibles? ¿Cuáles son las principales amenazas que pesan sobre nosotros con este tipo de situación?

Natalia: Para contestar eso yo voy a hablar de la situación de Brasil, porque claro, la conozco muy bien. Entonces lo que pasó en Brasil, y voy a hacer una toma histórica.

Silvia: Natalia nos contó que para el ataque a los Tres Poderes de Brasil fueron clave las narrativas creadas en las plataformas digitales, elaboradas para difundir información falsa sobre las elecciones. Esto dio origen a iniciativas legislativas, como la que frenó las big tech, que hemos contado en este episodio. Pero las tácticas, en Brasil, fueron más allá de un lobby agresivo.

Natalia: Y durante algún tiempo, algunos meses, parecía o estaba muy claro que los parlamentarios tenían mayoría para aprobarlos, pero las big tech, y ahí nosotros de Agencia Pública hicimos esta investigación, hicieron un par de cosas bien violentas. Por ejemplo, nosotros descubrimos que Meta, específicamente una de las personas que es Policy Director, elaboró una estrategia mentirosa de convencer a los congresistas evangélicos que si se pasara la ley, la Biblia sería censurada. Después cayó en las redes sociales y en los influenciadores gospel, evangélicos, y ahí la gente se quedó con mucho miedo, la gente normal. Me van a censurar la Biblia, imagínate. Y era una mentira, eso era una desinformación, mentira. Por otro, descubrimos que esas mismas big tech, por un grupo que es un grupo de lobby que se llama Conselho Digital, ayudó a organizar y apoyar a grupos que fueron a los aeropuertos a crear una manifestación en contra de la ley que no existía, ¿verdad? Era gente que fueron llevadas ahí para intentar dar la impresión a los parlamentarios que había un rechazo popular a la ley.

Las big tech se aliaron a la extrema derecha de Jair Bolsonaro diciendo que la ley iba a censurar a los ciudadanos. Google compró términos en el mismo Google, en la búsqueda de Google, que decía PL da censura, proyecto de ley de censura. Y al final Google hizo una cosa que tal vez fue la más radical de todas, que fue, tres días antes de que se votara el proyecto, la búsqueda de Google en Brasil, esta que todos nosotros utilizamos, decía: el proyecto de ley va a cambiar la internet, va a empeorar la internet que tú utilizas todo el día o el proyecto de ley va a hacer que tú no sepas qué es verdad y qué es mentira en la internet. Eso, 85% de los brasileños utilizan la búsqueda de Google. Toda la gente lo vio. Y no era, por ejemplo, esta es nuestra visión, aquí hay otra. No, era un editorial que llegó a toda la gente y causó un miedo social profundo. El hecho de que pueden hacer, el hecho de que pueden hacer eso ya debería hacer que todos los gobiernos se sentaran para pensar en cómo regularlas.

Eliezer: Natalia Viana, muchas gracias por hablar con nosotros.

Natalia: Está bien, querido. Lo siento por el portuñol, pero por ahí vamos.

Silvia: Este episodio fue producido por Franklin Villavicencio. Lo editamos Eliezer y yo. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido y la música son de Elías González.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Mariana Zúñiga, Daniela Cruzat, Samantha Proaño, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Eliezer Budasoff: Before we begin, we want to remind you that our donation campaign continues until December 31st, so if you haven’t had the chance to support us, this is a great moment. At El hilo we believe in the value of good journalism, the kind that goes deep, that provides context, that seeks to clearly explain what’s happening in our region. But that journalism is costly and requires a lot of effort and care. If you’ve been listening to us for a while and value the work we do, this is the moment to support us.

Silvia Viñas: Additionally, this week we achieved something very special: thanks to the effort of a group of donors, we’ll be able to triple every contribution you make up to a total of 20 thousand dollars. If, for example, you donate 30, we’ll receive 90. Go to elhilo.audio/donar. The size of your contribution doesn’t matter. Everything counts. Thank you so much! And if you’ve already done it, please send this link to your loved ones so they can support us too. Remember: elhilo.audio/donar. Thank you for supporting independent journalism!

Here’s the episode.

Eliezer: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: And I’m Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: Between late 2024 and mid-2025, in Colombia and Brazil, two key regulations that focused on social media were blocked.

Archival audio, Colombian Congress: I have presented a motion to eliminate this article, as it borders on censorship.

Archival audio, Brazilian news [in Portuguese]: Former president Michel Temer is hired by Google to help in the negotiation of platform regulation on the internet.

Silvia: These two initiatives, an article and a bill, sought to reduce the impact that platforms can have on the mental health of minors or on democracy. It’s hard to think that anyone could oppose protecting such things, but the attempt to set limits on online content directly affects the interests of a handful of companies that have become a power in themselves around the world.

Eliezer: The way these regulations were blocked made it clear that in both countries there were coordinated actions to change wills, intervene in institutional processes, or build narratives that favored the big tech companies. A multinational investigation led by the Brazilian media outlet Agencia Pública and the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism, CLIP, has made some of these strategies visible, and the challenge it poses for our countries to face a power like that of big tech.

Silvia: Today, how a lobbying network operates that seeks to influence national policy and reduce regulations on big tech companies in Latin America.

It’s December 12, 2025.

Archival audio, Olga Lucía Velásquez: In the last debate in the Senate they removed that element that brought sanctions for content that affected mental health, with the argument that, well, it was going against free expression.

Silvia: You’re listening to Colombian congresswoman Olga Lucía Velásquez during an interview conducted in June of this year. She is one of the authors of a mental health bill, one of the regulations we mentioned at the beginning of this episode. That bill had an article, number 8. It sought to sanction platforms if they failed to comply with codes of conduct established by Colombia’s Communications Regulatory Commission, the CRC.

Eliezer: This article triggered the deployment of a lobbying machinery by big tech companies, like Meta, whose goal was to soften the regulation. Suddenly, some legislators began to speak in defense of what they called “the multiple internet stakeholders.”

Archival audio, Colombian Congress: A number of trade associations are requesting that article 8 be eliminated. Why? Impact on freedom of expression. The possibility that a single actor like the CRC could intervene in digital content could lead to decisions that don’t take into account the multiple internet stakeholders.

Silvia: The law is considered a historic milestone in Colombia for its scope on mental health, and it ended up being approved for the most part. But along the way it sacrificed something important: protecting children and adolescents from harmful content on digital platforms. Instead, it left in the hands of big tech companies a regulatory function in which, for the bill’s authors, state participation was necessary.

Eliezer: Something similar happened in Brazil. Big tech managed to block a bill that sought to regulate digital platforms like Facebook, Instagram and Google. It demanded greater responsibility and transparency after the assault on the Three Powers carried out by followers of former president Jair Bolsonaro, who this year was sentenced to 27 years in prison for a coup plot.

Archival audio, Brazilian news [in Portuguese]: In a statement, Google issued a public statement about the bill and says they invested in marketing campaigns to give visibility to the points the company understands as concerning.

Silvia: To understand how this lobbying and political pressure operation works, we spoke with Natalia Viana, a Brazilian journalist and co-founder of the media outlet Agência Pública. Agência Pública and CLIP worked together on a transnational and very broad investigation about big tech and its network of influences.

Eliezer: You called it “the invisible hand” and in a way the work you do is to make it visible. But to start, can you tell us a bit, first, who makes up this group of multibillion-dollar companies?

Natalia Viana: Well, to start, what is big tech? Big tech is a somewhat broader term that… It talks about companies that are unique in the history of capitalism, that have managed to obtain extremely high profitability and profit, and that have also managed to control a large part of the digital economy. So, there are five or six big sisters as they say, which are Amazon, Meta from Facebook, Instagram and Whatsapp, Alphabet from Google, among them there’s also Apple. Here in Latin America we have Mercado Libre, which is gigantic, as well as Rappi.

Silvia: But there are also others that have recently entered this category, like TikTok and OpenAI, which owns ChatGPT.

Natalia: They’re talked about much like we talk about big oil or big food—they’re the largest in the tech industry.

Eliezer: You just mentioned having managed to control or possess most of the digital economy. What you’re talking about, that this magnitude of companies within capitalism had never been seen before. What is the economic, social and political weight that these companies have in the world? But especially in Latin America.

Natalia: Well, I think there are some characteristics of this economic sector that are unique in history, but that’s one factor. There’s another factor which is the extreme concentration of markets, and yes, it replicates around the world and in each country. So, if you look, for example, at the control of the search market, the control of the chat market, the control of the social media market, the control of the streaming market, of podcasts, etc., etc., they’re also almost all either a monopoly or an oligopoly. Google’s control over searches, for example, is crazy. It’s more than 80% in almost all countries.

Archival audio, RTVE: Google is a monopoly, so a federal court in Washington has ruled. It assures that the search engine controls 90% of searches in the United States and that it has left millions of dollars in exclusivity contracts.

Natalia: In all countries, these companies have the same power. And this power is the power to determine conversations between people.

Eliezer: Right. Just in recent years, but especially in the most recent years, we’ve seen how some of the main figures, the CEOs of these companies, have a relevant role within the circles of political power. The clearest is how we’ve seen it in the relationship between the CEOs and Donald Trump during his new government. From going to his inauguration to meeting for dinner at the White House.

Archival audio, Mark Zuckerberg [in English]: Thank you for inviting us. This is quite a large group and, I mean…

Archival audio, news: Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates and Tim Cook were there, among others.

Archival audio, Sergey Brin [in English]: And the fact that your administration is supporting our companies instead of fighting with us.

Archival audio, news: This dinner is the most recent example of a delicate two-way courtship between Trump and tech leaders.

Archival audio, Donald Trump [in English]: Bill, do you want to say a few words?

Archival audio, Bill Gates [in English]: Thank you for your incredible leadership. I want to thank…

Eliezer: What is this dynamic of big tech with Latin American governments? How do they navigate these waters?

Natalia: There are different actions in different countries. In general, almost all of these big tech don’t pay attention, don’t have offices, and don’t have people in the countries. So, in fact, they treat Latin Americans, even Latin American governments, like second class. So they act very strongly whenever there are laws that in fact go against their interests, but they act a lot through transnational associations. So, there are associations like ALAI, which is the Latin American Internet Association.

Silvia: We could say that ALAI is a key alliance of tech companies that operates as one of the main lobbying or influence tools for these corporations in the region. Natalia explained to us that ALAI acts in several countries at the same time. They say they don’t represent the interests of any tech company, but investigations like those done by CLIP prove otherwise.

Natalia: So, if you look at the guy, the president, the representative of ALAI, he goes to many congresses to act. In Brazil’s case, it’s different, because Brazil is one of the largest markets for big tech. So, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, etc. For Brazil there’s a much more robust operation.

Eliezer: For example, in Brazil, a media outlet that participated in the investigation, Núcleo Jornalismo, identified that Meta is the company with the most professionals in the areas of public policy or government relations. Between 19 and 75 names were identified in the country.

Natalia: But there are 74 employees of big tech, in addition to lobbying offices, in addition to associations, in addition to people who are co-opted or who speak about their interests, etc. And this is a very large group. That’s in Brazil.

Silvia: There are other cases too, like Mexico, where officials and lobbyists are opening doors for big tech companies so they can install data centers in the state of Querétaro. These centers are enormous warehouses that house thousands of equipment running day and night and consume millions of liters of water daily. And there’s the case of Chile, where there are already 49 of these centers and there are plans to open more. A couple of weeks ago we published an episode about this.

Eliezer: All this, moreover, in a context where it mixes with geopolitics and the interests not only of these big companies, but also of the United States.

Natalia: For me it’s a very interesting issue that tech companies have gotten so close to Trump and that on the other hand, Trump is using the defense of tech companies against regulation as one of the main axes in negotiation with all the countries of the world, with threats.

Silvia: In September, Trump announced that he’s going to apply tariffs and restrict exports to any country that regulates his tech companies.

Natalia: That shows that this is the biggest global battle and that they are now inside the government, close to the government, so that regulation is prevented.

Eliezer: We’re taking a break and we’ll be back.

Silvia: We’re back on El hilo.

Eliezer: Many of the strategies these companies use, when you mention them, remind you a bit of those used by tobacco companies, or big alcohol companies, which mixed lobbying, buying influence, studies or analyses that weren’t entirely objective. But from what you tell us and what the investigation talks about, it seems that big tech amplifies it, right? It’s like this on steroids. Can you explain a bit how it differs from the dynamics that other industries have established in the past?

Natalia: The simple fact that they have much more money, but a lot, a lot of money. As I told you, they have become the most powerful lobbying group in many countries, even in the United States and in Europe and also in our countries. It’s a fact, let’s say, relevant in itself. But big tech can potentialize their negotiating power because nowadays politicians need big tech to get elected. So, for example, in Brazil, but also in other countries, one way to be allies or close to the parties is to give them training in their tools, is to leave employees to serve politicians at any time of day or night if they have problems. So, if you have problems with your Facebook, you’re never going to be able to talk to a person from Facebook. If you’re a congressman, they accept you, they talk to you immediately.

Silvia: That is, the networks have become a central actor in Latin American politics. Not being on them, whether during the campaign or after, is like not existing on the political board.

Natalia: And there’s even a political alliance they’re making in Brazil, and they did it very strongly with the extreme right politicians who came to power through the power of the networks, through Facebook, for example. So, this alliance becomes closer and closer and more and more natural. And after they’re now allies of Donald Trump, even, I believe they left, let’s say, the political neutrality they always had. Many congressmen are afraid of becoming their enemy, because today a politician in Latin America needs the platforms to get elected, to talk to their constituents, to their voters.

Archival audio, news: Right-wing candidate Jair Bolsonaro acknowledged through a live broadcast on Facebook that social media has a lot to do with his lead in Brazil’s presidential polls.

Archival audio, news: On Twitter, the right-winger once again recalled the ties of his rival’s party to corruption.

Archival audio, Jair Bolsonaro [in Portuguese]: I ask, in this final stretch of elections in Brazil, just two minutes of your attention.

Natalia: On the other hand, decisions are very concentrated in a very small group of executives in Silicon Valley. So, the way lobbying works is super concentrated and that’s why it replicates in many places. One of the characteristics, for example, is gratuity. The little gifts they give. Because all these companies have, for example, compliance rules that they can’t pay tips. But they can give, for example, take you to lunch or dinner or happy hours. And, for example, I know that in one of them, at Meta, they can spend 150 dollars on dinner with a congressman. In Brazil, 150 dollars is a lot of money for a dinner. But since decisions are made in the United States, that’s fine there. So, they have a lot of power. And since decisions are made there, there are things that in our realities are very powerful, like this. That’s just one example.

Eliezer: Once this lobbying machinery gets going, let’s say, beyond the specific cases we’re going to talk about now, what types of regulations do they usually seek to block? And what are the Latin American countries in which this influence has been documented?

Natalia: Well, we documented this influence in Colombia, Argentina, Chile, Mexico and Ecuador. And also, obviously, Brazil. There are a couple of laws, what’s being attempted to regulate in the world and also in Latin America. First, laws that defend children’s rights.

Silvia: For example, the one we talked about at the beginning, the one from Colombia. Which sought to expand moderation on issues that can affect children and adolescents.

Natalia: Another is accountability for what is published, which is the issue of fake news or disinformation. If the published content is illegal in the world, outside the digital realm, it should also be in the digital realm. That’s what Brazil tried to do, for example. Another thing being attempted to regulate is the question of competition, as I was saying. So, since they have control of entire markets, there have to be rules. If they have that control, then a part has to be broken up or given to a national competitor. And there’s also another issue which is the issue of taxes, right? They have to pay taxes, how much to pay, etcetera, etcetera. That’s what’s happening in various places.

Eliezer: Let’s stop for a bit on some of the cases you just mentioned. Colombia’s, for example, which was very close to forcing tech giants to be accountable for content that affects the physical and mental health of children, right?, of minors. However, this was truncated by big tech. How did it happen?

Natalia: This, well, a bit with what I was saying, those transnational associations, also the big tech lobbyists themselves went to present in Congress, present their points, etcetera. They achieved many alliances that gave them a lot of time to defend their visions. But something also happened there, which happened a lot in Brazil and which is perhaps the most violent thing big tech is doing. Which is to associate any attempt to regulate them and regulate them simply to mitigate the damage they cause to society with an attempt at censorship.

And they did it in Colombia—they also did it in Brazil—with an alliance with the extreme right. And there, on social media itself, this narrative that trying to regulate is censorship, grows and becomes almost preventing discussion. Also another thing they do a lot and that also happened in the Colombian case, is that some of those international groups finance trips where congressmen go to their offices, to their headquarters, and there they have a very good time, receive more gifts, talk to people who are very intelligent and who know everything about technology, which is also a way of seduction. And there we mapped, the people from CLIP specifically, mapped some of those meetings where interests are mixed a lot with having a good time.

Eliezer: We’re taking one last break and we’ll be back.

Silvia: We’re back.

Eliezer: We have the case of Brazil, where Google hired former president Michel Temer to lobby for the so-called fake news law, something you mentioned a little while ago. And other profiles have been hired like this, from public management to regulatory agencies. You have called this dynamic “the revolving door.” Could you explain to us what it means and how it works?

Natalia: Well, the revolving door seemed like a super important issue to us, because I return to the investigation that Núcleo Periodismo did. In Brazil, there were 74 big tech employees who work in the Policy, Public Policy, or Global Affairs, or Public Affairs departments. These are people who are hired to try to shape laws to the interest of big tech. There’s no other description of their job than that. And so, they’re lobbyists. These people bring, obviously, their knowledge of how the public sphere works, governments, but more than that, because they bring their alliances, their friendships, their influence, and facilitate the entry, let’s say, the infiltration, of big tech arguments inside governments. In Brazil, Michel Temer, who was a very relevant president, who took office after Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment, was hired almost at the end of the entire strategy by big tech to kill the regulation that came closest, which was the fake news law.

Archival audio, news: The federal government is going to try a new approach with Congress so that the issue of digital platform regulation returns to legislators’ agenda. The bill, also known as the fake news PL, is still stalled…

Natalia: And Michel Temer has a lot of influence since the Constituent Assembly. So, if Michel Temer calls anyone in Congress, they’ll receive him. Because Michel Temer, who is a lawyer, has influence in the Supreme Court. You know that Brazil’s Supreme Court is in a fight with big tech. But a violent fight, because they’re trying, in fact, to hold them responsible for what was the coup attempt in 2023.

Eliezer: Natalia is referring to the attack on the Three Powers in Brasilia, in January 2023. Former president Bolsonaro was convicted in September of this year as responsible for leading a conspiracy to discredit the Brazilian electoral system, attack institutions and deny the results of the elections he lost against Lula.

Silvia: This coup attempt led Brazil’s Supreme Court to make the decision to declare Article 19 of the Civil Rights Framework for the Internet unconstitutional. The article said that platforms are not responsible for what people posted. Only if a judge ordered them to delete something illegal and they didn’t.

Archival audio, news: The decision affects companies like X, TikTok, Instagram and Facebook, which from now on must immediately delete publications that promote anti-democratic actions, terrorism, hate speech, child pornography and other crimes.

Natalia: So those very high-profile names, they open doors, and of course, they charge a lot for it. Another example that, to me, seems super relevant, is the example of Tony Blair. Tony Blair has his institute, which is the Tony Blair Institute, in England. And the Tony Blair Institute, which previously worked on issues like inequality, terrorism, etc., a couple of years ago, started working on state modernization, and how is it done? By using artificial intelligence. What did we discover? And this was discovered by Lighthouse Report, which is a European organization, which was also a member of this investigation. The Tony Blair Institute received hundreds of millions of pounds from Oracle’s founder, Larry Ellison.

Silvia: Maybe Oracle doesn’t ring a bell in the AI race, because it’s not as common to hear about as ChatGPT and other chatbots. But it’s one of the big ones in the industry. Above all, it has focused on areas like medicine, services for governments and cloud services. It’s also the company that owns the Java programming language. In recent months, Oracle took on a supervisory role in the transfer of TikTok’s operations, of Chinese origin, to the United States. Oracle will have access to the social network’s algorithm.

Natalia: And even, at some moments that we managed to obtain with documents or with a lot of cross-referencing of diverse sources, while they’re working with governments that need to adopt artificial intelligence to improve public management, etc., they say “perhaps Oracle’s strategy or perhaps Oracle’s tool is the best they can use.” So, there it’s absolutely disguised lobbying.

Eliezer: Looking at this panorama we have in the region with fragile policies and unprotected societies, what do civil organizations, users and states face against these invisible hands? What are the main threats hanging over us with this type of situation?

Natalia: To answer that I’m going to talk about Brazil’s situation, because of course, I know it very well. So what happened in Brazil, and I’m going to take a historical view.

Silvia: Natalia told us that for the attack on Brazil’s Three Powers, the narratives created on digital platforms were key, designed to spread false information about the elections. This gave rise to legislative initiatives, like the one big tech block, which we’ve told about in this episode. But the tactics, in Brazil, went beyond aggressive lobbying.

Natalia: And for some time, some months, it seemed or it was very clear that the parliamentarians had a majority to approve them, but big tech, and we at Agencia Pública did this investigation, did a couple of very violent things. For example, we discovered that Meta, specifically one of the people who is Policy Director, developed a mendacious strategy to convince evangelical congressmen that if the law passed, the Bible would be censored. Then it spread on social media and on gospel, evangelical influencers, and people got very scared, normal people. They’re going to censor the Bible, imagine. And it was a lie, that was disinformation, a lie. On the other hand, we discovered that those same big tech companies, through a group that is a lobbying group called Digital Council, helped organize and support groups that went to airports to create a demonstration against the law that didn’t exist, right? They were people who had been taken there to try to give parliamentarians the impression that there was popular rejection of the law.

Big tech companies allied themselves with Jair Bolsonaro’s extreme right saying that the law was going to censor citizens. Google bought search terms on Google itself, on the Google search, that said PL da censura, censorship bill. And in the end Google did something that was perhaps the most radical of all, which was, three days before the project was to be voted on, Google search in Brazil, which we all use, said: the bill is going to change the internet, it’s going to worsen the internet you use every day or the bill is going to make it so you don’t know what’s true and what’s a lie on the internet. 85% of Brazilians use Google search. Everyone saw it. And it wasn’t, for example, this is our view, here’s another. No, it was an editorial that reached everyone and caused profound social fear. The fact that they can do that should already make all governments sit down to think about how to regulate them.

Eliezer: Natalia Viana, thank you so much for talking with us.

Natalia: It’s fine, dear. Sorry for the portuñol, but that’s how we go.

Silvia: This episode was produced by Franklin Villavicencio. Eliezer and I edited it. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design and music are by Elías González.

The rest of El hilo’s team includes Mariana Zúñiga, Daniela Cruzat, Samantha Proaño, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask you to join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to learn more about today’s episode, subscribe to our email newsletter by going to elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it every Friday.

You can also follow us on our social media. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook and Threads. You can find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share episodes.

Thank you for listening.