Aranceles

Donald Trump

Guerra de aranceles

Guerra comercial

Estados Unidos

México

Canadá

China

Acero

Aluminio

Agricultores

Manufacturas

Recesión

Los aranceles que prometió Donald Trump en campaña ya son una realidad, y ya tienen consecuencias. En medio del caos de los anuncios, las amenazas, los retrocesos y las represalias estamos todos nosotros, que tarde o temprano vamos a sentir el impacto de estas medidas en la vida cotidiana. Queríamos entender el costo real de la errática guerra de aranceles del gobierno de Estados Unidos, así que hablamos con Sara Ávila, economista mexicana y profesora en la Universidad de Colorado Boulder. Sara nos explica en términos claros cómo funcionan los aranceles, sus efectos en América Latina y por qué los mercados que celebraron el triunfo de Trump ahora son un reflejo de la incertidumbre económica global.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Nausícaa Palomeque -

Edición

Silvia Viñas, Eliezer Budasoff -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción en redes sociales

Samantha Proaño, Natalia Ramírez, Daniela Cruzat, Juan David Naranjo Navarro -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Elías González, Remy Lozano -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

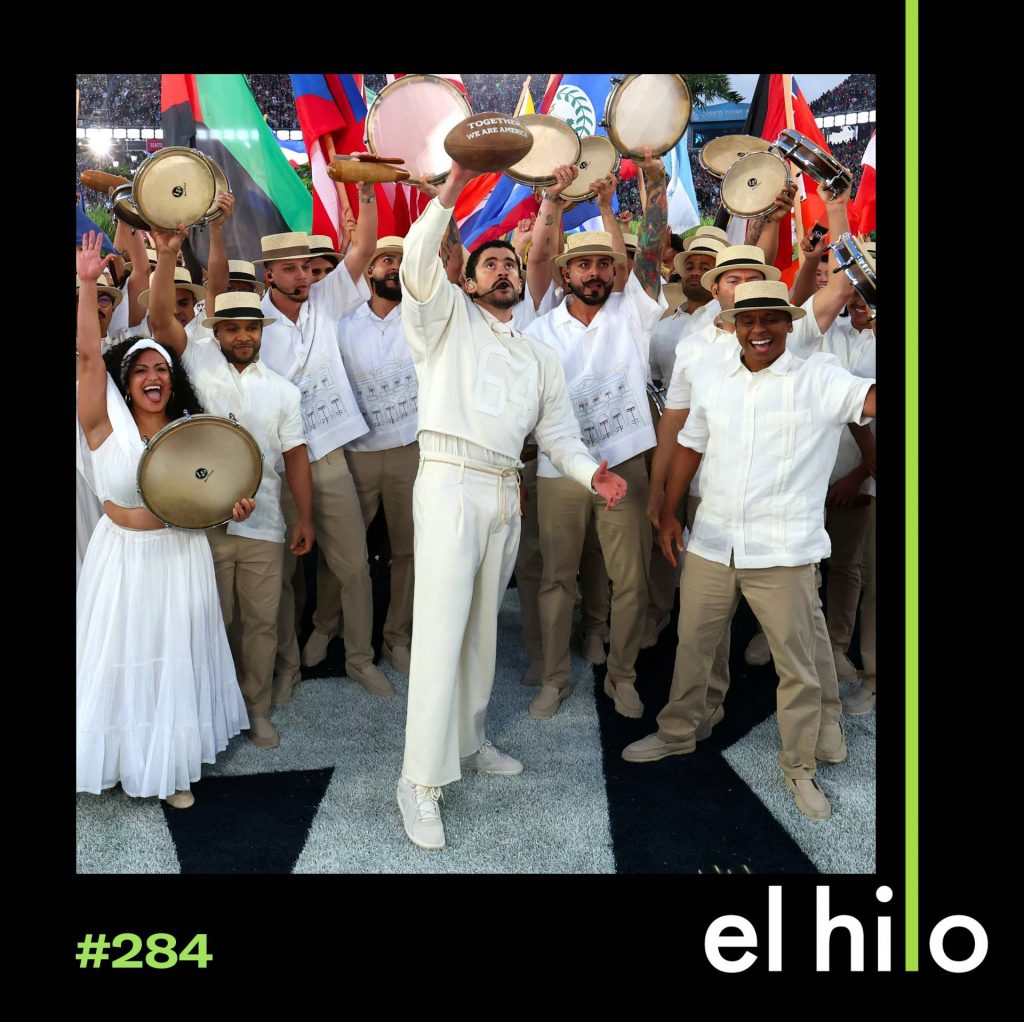

Fotografía

Getty Images / Cristopher Rogel

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Esta historia de El hilo fue producida con el apoyo de Grupo SURA, gestor de inversiones con foco en servicios financieros. SURA impulsa el periodismo independiente que fortalece la democracia en América Latina y contribuye a una ciudadanía mejor informada

Eliezer Budasoff: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia Viñas: Y yo soy Silvia Viñas.

Hace solo dos meses que Donald Trump está de vuelta en el gobierno y ya se desató una guerra comercial de aranceles.

Audio de archivo, presentador: El presidente de Estados Unidos, Donald Trump, anunció que impondrá aranceles del 25% a las importaciones de acero y aluminio.

Audio de archivo, presentador: La amenaza arancelaria mantiene en vilo a México y a Canadá que han amenazado con represalias. China también se prepara para el embate.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: Y prometió tomar las contramedidas correspondientes.

Eliezer: Trump está cumpliendo con una de sus promesas de campaña. Ha vendido estos aranceles como una panacea. Dice que van a bajar la deuda, que van a revivir al sector manufacturero de Estados Unidos. Que van a presionar a países como México a detener el flujo de fentanilo y de migrantes.

Silvia: Y en medio del caos, de las noticias sobre anuncios, amenazas y represalias, es fácil confundirse, perder la perspectiva. Pero la realidad es que esta guerra comercial tiene un impacto directo en todos nosotros, los consumidores. Esta semana, la OCDE bajó sus estimaciones de crecimiento económico para este año y el próximo. Y México sería el país más afectado. Podría entrar en recesión. El organismo predice que va a subir la inflación en todo el mundo.

Hoy, el costo real de la guerra de aranceles de Trump. Es 21 de marzo de 2025.

Silvia: Sara, se ha hablado mucho de aranceles. Parece que cada día hay una noticia nueva. Está cambiando a cada rato, pero queremos entender lo más básico: ¿Qué es un arancel?

Sara Ávila: Bueno, un arancel es un impuesto que grava a las mercancías que se importan de otros países.

Eliezer: Ella es Sara Ávila, economista mexicana y profesora en la Universidad de Colorado Boulder.

Sara: Por ejemplo, digamos que esta es una bolsa que cuesta 10 dólares. Y si tú le pones un arancel del 20%, cuando yo importo esta bolsa de México a Estados Unidos, entonces tengo que pagar dos dólares por esta bolsa. Ese es el arancel.

Silvia: Y antes de que empezara esta guerra de aranceles no les prestábamos mucha atención, pero obviamente existían. Entonces, por ejemplo, ¿cómo funcionaban los aranceles entre Estados Unidos y México?

Sara: Hemos tenido aranceles en el pasado, pero en las últimas décadas, desde que yo soy niña, yo ya tengo 50 años, entonces cuando yo era pequeña había muchísimos aranceles. Era carísimo conseguir dulces de Estados Unidos, era un lujo tener mochilas de Estados Unidos porque teníamos muchos aranceles. Conforme ha pasado el tiempo los aranceles han ido disminuyendo, sobre todo entre México, Canadá y Estados Unidos, de tal modo que ahora podemos vender y comprar productos entre nosotros sin pagar dinero extra. Entonces tenemos autos, computadoras, bolsas, mochilas, lápices y aguacates, mangos, piñas en todas partes sin pagar dinero adicional. Entonces, esta manera de vivir nos ha permitido tener más mercados, más negocio y más riqueza. Así es como ha funcionado.

Silvia: Ahora, Trump insiste en que los aranceles no van a subir los precios para las personas, pero queremos entender en realidad quién carga con el costo de los aranceles.

Sara: Sí, al principio, cuando tú llegas al país tienes que pagar tus dos dólares, ¿no? No importa que los sacas de tu producción. Aquí están los dos dólares. Sin embargo, lo que va a pasar es que probablemente tú quieras aumentar el precio de tu bolsa. Ya no va a costar 10 dólares, sino 12.

Cuando llega al consumidor, el consumidor decide si la compra o no. Si el consumidor necesita este bien o le encanta este bien y quiere seguir pagándolo, pues le va a doler en el codo, pero lo va a seguir comprando. Pero pues va a llegar un momento en el que algunos consumidores no les alcance. Algunos consumidores ya no les interese y algunos van a dejar de comprarlo. Se va a perder un pedacito de mercado que ya no va a comprar este producto. Por lo tanto, el productor de bolsas va a decir ¿sabes qué? Ya no voy a producir tantas bolsas. Esta pérdida en producción, venta y compra de bolsas es lo que se le llama una pérdida en bienestar. Y esta pérdida en bienestar es tangible. Son las piñas que ya no se produjeron, son los mangos que ya no se cosecharon. Es el maíz, es el acero, es todo lo que ya no se produjo y ya no se compró y ya no se hizo. Son negocios que ya no se hicieron, inversiones que ya no se hicieron y empleos que ya no se crearon. Esto es una pérdida en bienestar social, esa la paga toda la sociedad. Y entre quién la paga, si el consumidor o el productor, va a ser o el consumidor en el país del arancel, que como quiera ama este producto y va a seguir pagándolo, o el productor que necesita venderlo y pues va a absorber el costo.

Eliezer: Ya han hecho algunas estimaciones sobre el impacto de los aranceles de 25% a Canadá y México, y el de 10% a China. Según el Instituto Peterson de Economía Internacional, esto hará que una familia promedio de Estados Unidos gaste 1,200 dólares más al año. Cálculos que incluyen otras variables comerciales estiman que podría ser cerca de 2000 dólares al año.

Silvia: La mayoría de los productos importados que se consumen en Estados Unidos ya pagan aranceles, pero más bajos. El promedio suele ser de 2,5%. Ese número es importante para dimensionar esta crisis comercial. Estamos hablando de 10%, 25%. Incluso Trump llegó a amenazar con aranceles de 50%.

Eliezer: Además de los aranceles a Canadá, México y China, el 12 de marzo Trump impuso un arancel de 25% a todas las importaciones de acero y aluminio. A todos los países.

Sara: Afecta a Brasil, afecta a México, afecta a Canadá, incluso Europa y la mayoría de los países han contestado, China, por supuesto, han contestado con aranceles inmediatos.

Eliezer: O sea, le han puesto aranceles de vuelta a Estados Unidos. Otro país de la región perjudicado es Argentina, cuyo gobierno es aliado de Trump. El 40% del total de las exportaciones de aluminio de ese país van a Estados Unidos. Y la cámara argentina del acero le pidió al gobierno que negocie con Estados Unidos para dar marcha atrás con los aranceles.

Silvia: Los aranceles al aluminio y el acero son importantes porque estos metales se usan en muchos productos, como maquinaria, autos, electrodomésticos, dispositivos médicos. Sara nos explicó que a veces el impacto comienza con una pieza y se va expandiendo a todo el proceso de producción. Esto pasa por ejemplo con los autos.

Sara: Son procesos productivos que tienen incluso varias fases donde el tornillo se produce acá se manda a Canadá, Canadá lo ensambla, esa parte se manda acá, la ponemos en el auto y entonces ya se vende en Estados Unidos. A la hora de que pones aranceles no solamente aumentas el precio del tornillito, sino probablemente también el precio de el birlo y el precio de la llanta y el precio de la puerta. Y entonces esto va creando un efecto dominó que al final el precio de un auto va a encarecerse considerablemente. Por eso es que la industria automotriz en Estados Unidos le rogó a Donald Trump que no hiciera esto, y Donald Trump se echó para atrás en algunos casos, ¿verdad? Porque es muy doloroso para esta industria que, de por sí estaba en problemas, ahora con mayores costos gracias a estos aranceles, ¿cómo no?

Eliezer: Otro sector que puede quedar muy afectado es el agrícola. Si no hay ningún cambio, el aumento en los aranceles entrará en vigor el 2 de abril.

Silvia: Cuando Trump los anunció, publicó un mensaje para los agricultores en su red social Truth Social. Cito: “prepárense para empezar a producir mucho más producto agrícola para vender dentro de Estados Unidos.” Y remató con “¡Diviértanse!”.

Eliezer: Pero los agricultores ya están sufriendo el impacto de estas medidas. Dependen de la exportación. Y China, por ejemplo, respondió a Trump con aranceles del 10% al 15% a productos como trigo, maíz y carne de cerdo. A esto se suman recortes del Departamento de Agricultura y otras agencias, que también están afectando directamente a los agricultores.

Silvia: Y esta guerra de aranceles, claro, tiene un impacto directo en América Latina también.

Sara: En realidad, nosotros como latinoamericanos dependemos mucho del mercado estadounidense. Gran parte de nuestras exportaciones va al mercado estadounidense. En general, nosotros producimos, por supuesto, servicios agrícolas, productos agrícolas, aguacate, piñas, uvas.

Eliezer: Colombia le exporta a Estados Unidos café, banano y flores; Perú uvas; Argentina vino, miel y soja; México cerveza, aguacate, tomate…

Sara: Y en cualquier caso, como latinoamericanos, una guerra de aranceles nos afecta muy negativamente. Todos nuestros precios aumentan muchísimo. Nosotros tenemos mercados de un tamaño considerable, pero definitivamente todos somos mucho más ricos cuando tenemos un mercado más grande a quien venderle nuestros productos. Y al poder tener acceso al mercado americano, nosotros podemos venderle nuestros productos a ellos y ellos pues son muy felices de comprarnos nuestros productos. Ahora sí que todos felices, ¿no? Nosotros vendiendo y ellos comprando. En el instante en el que se ponen barreras a esta actividad, nosotros salimos perdiendo y bueno, y ellos también al no tener acceso a productos tan económicos como los que nosotros otorgamos.

Silvia: Estas medidas impactan en el mercado de trabajo y en las oportunidades. Sara resaltó que las empresas que exportan suelen dar trabajos formales, que generan cierta estabilidad laboral.

Sara: En el instante en el que tú le aumentas los costos a estas empresas y empieza a sufrir pérdidas, entonces perdemos empleos buenos que se van hacia la informalidad. Y el problema en irnos hacia la informalidad es que perdemos toda esta capacidad de planear a futuro, esta capacidad de tener acceso a créditos. Esta capacidad de tener un fortalecimiento del sistema financiero. Y entonces vamos regresando a situaciones que no ayudan a absolutamente nadie.

Eliezer: Una pausa y volvemos.

Silvia: Este episodio viene con el apoyo de Noticias Sin Filtro, una app que te conecta con el periodismo independiente de Venezuela.

Eliezer: Cada vez más, el acceso a la información en países de América Latina está en riesgo. Los bloqueos a medios de comunicación independientes y las restricciones al uso de plataformas impiden llegar a información verificada y confiable. Y en lugares como Venezuela, para la gran mayoría de la población se está volviendo cada día más difícil encontrar las noticias que necesitan.

Silvia: Con Noticias Sin Filtro, en tu celular o en tu táblet, puedes acceder a fuentes independientes para mantenerte informado. Las noticias de los principales medios independientes del país, videos, programas de radio locales y podcasts, todo en un solo lugar.

Eliezer: Esta aplicación es una herramienta que puedes descargar a cualquier celular, hecha en alianza con medios independientes venezolanos para que la información esté siempre a tu alcance.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Silvia: Trump cumple dos meses en el cargo. Se siente como que ha sido mucho más porque han pasado muchas cosas. ¿El efecto de estos aranceles los consumidores ya los están sintiendo?

Sara: Mira, a cortísimo plazo todavía no, incluso yo fui a comprar aguacates de inmediato antes de que suban de precio y pues esta semana todavía no me afecta. Esta semana no nos va a afectar. No solamente eso, sino que el mercado estadounidense tiene muy buenos indicadores en este momento.

Eliezer: Tiene bajo desempleo, el PBI está creciendo, las tasas de interés siguen bajas.

Sara: Si no tuviéramos esta amenaza de aranceles, estaríamos mejor. Y el mercado en general empieza con la incertidumbre. No sabemos qué va a pasar y al no saber qué va a pasar, entonces la inversión se empieza a hacer más pequeña. Y entonces, si no estamos percibiendo en este momento el costo en nuestros bolsillos, pues va a tener que ser en el mediano o largo plazo. Desafortunadamente es un costo real que quizá no estamos sintiendo todavía, pero tarde o temprano se va a sentir y como es obvio que está pasando, incluso Trump está diciendo…

Audio de archivo, Donald Trump: There will be a little disturbance, but we’re OK with that…

Sara: Ah, bueno, pues va a ser doloroso, pero vale la pena. Él por supuesto que tiene en su mente objetivos que no necesariamente tienen que ver con el bienestar de los ciudadanos americanos, pero mucho menos de los ciudadanos latinoamericanos, ¿verdad? Parece ser que él entre sus objetivos es: tener poder, ser muy popular y tener un montón de personas que le digan que todo lo que hace está muy bien hecho.

Desafortunadamente, la evidencia muestra que Trump nunca ha sido muy estratégico. Trump ha caído cuatro veces en bancarrota. Eso nos dice que realmente muy estratega, muy inteligente y muy bueno para los negocios, no es. No es. Yo no creo que Trump tenga una estrategia inteligente para absolutamente nada. Sin embargo, algunos de sus consejeros sugieren que X, Y o Z puede ayudar a que aumente su nivel de popularidad, a que aumente su poder. Y él definitivamente lo que quiere es que Estados Unidos sea una superpotencia y que él sea reconocido en la historia como el presidente que aumentó el territorio de Estados Unidos, el que regresó las manufacturas y el fue el más amado por todos.

Silvia: Trump dice que quiere recuperar la industria manufacturera, las fábricas. Un sector que perdió muchos empleos en los últimos 40 años. Se han ido a países como México o China.

Sara: Y entonces él dice bueno, necesito que la manufactura vuelva a Estados Unidos y por lo tanto voy a poner aranceles en estas manufacturas que vienen de otros países.

Eliezer: Para Sara esto no tiene mucho sentido. Porque en un escenario de poco desempleo y de expulsiones de personas migrantes, no es tan fácil encontrar trabajadores para las fábricas.

Sara: Pues no hay personas dispuestas a elaborar estos trabajos. Entonces desde cualquier punto que tú lo veas, todos los expertos económicos concuerdan. Esto no ayuda a la economía de Estados Unidos ni a la economía de absolutamente nadie.

Silvia: ¿Qué otros objetivos tiene Trump con estos aranceles y estas amenazas constantes de poner más?

Sara: Creo que está usando las tarifas de aranceles más bien como una amenaza para hacer que los países hagan lo que él necesita que se haga. Pero realmente sus objetivos no están muy bien definidos. No hay una política que tú digas: Mira, lo que él quiere es incrementar la clase media, fuera de que aparentemente todas las estrategias que él ha llevado a cabo permiten que los ricos sean más ricos mediante menos impuestos, mediante el pago de menos impuestos y incrementar su poder como líder de el país más poderoso militarmente hablando. No se ve como que haya otro beneficio.

Eliezer: Como hemos visto, en realidad, el aumento de los aranceles va a afectar sobre todo al ciudadano de a pie, porque van a subir los precios de alimentos y bienes que consumen a diario.

Sara: Estamos hablando de maíz, de comida, como aguacate, frutas, estamos hablando de bolsos, de sillas, de mesas, de cosas con aluminio. Este tipo de cosas las compran la clase media y la clase pobre. No estamos aumentando las tarifas de yates lujosos, viajes lujosos. Eso realmente no se ve afectado y es muy, muy curioso, ¿no? que a la larga, bueno, realmente quienes pagarían por estos serían o las empresas que producen estos bienes o los consumidores que consumen estos bienes, ¿no? Entonces, incluso para el mercado norteamericano, está siendo una muy mala estrategia.

Silvia: Él dice que está haciendo esto de los aranceles para, no sé, reducir el flujo de fentanilo y el flujo de migración de México, ¿no? Para devolver estos trabajos que se han ido a otros lados y reducir la deuda. ¿Pero le está funcionando? O quizás es muy temprano para ver eso.

Sara: Definitivamente una política de aranceles no le va a ayudar a disminuir la deuda. No le va a ayudar a mejorar el bienestar de los consumidores norteamericanos. Le va a ayudar a aumentar los precios, le va a ayudar a disminuir el crecimiento económico, le va a ayudar a proteger a un sector manufacturero, probablemente, que ya no existe. Y aquí nada más te quiero comentar cómo está la cosa. Digamos, cronológicamente, los países, vamos a decir que los más pobres se dedican a la agricultura, conforme van creciendo económicamente se dedican a la manufactura, como fue Estados Unidos. En una época en la que muchos trabajadores trabajaban en fábricas y tenían trabajos bien remunerados. Pero conforme va creciendo la economía y, digamos, una familia se vuelve más rica, ya compró todas las mansiones que podía, ya compró todos los autos que podía, ya compró toda la ropa que podía. Ya hay un límite. ¿Qué es lo que haces? Compras un buen restaurante, un viaje, un servicio. Es una economía de servicio. La economía gringa, la economía norteamericana, se dedica a los servicios porque es lo que más reditúa. Y por alguna extraña razón, Trump quiere regresar a la manufactura. No tiene ningún sentido. Probablemente él quiere apelar a esta base de americanos que añoran con este pasado de fábricas, de personas que trabajaban con sus manos y producían autos y muebles. Eso ya se acabó e incluso si regresas a hacer eso, es una recesión al pasado, a cosas menos productivas, a cosas menos valiosas. No tiene caso. Alguien le tiene que decir que esto no tiene caso. Y él está convencido de que al regresar a esto todo este sector va a resurgir. Todo este sector va a volver a tener poder adquisitivo. Y eso no es verdad.

Eliezer: Vamos a hacer otra pausa, y a la vuelta, Sara nos explica la reacción de los mercados a los aranceles de Trump, y cómo podemos navegar la incertidumbre económica. Ya volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Silvia: Cuando Trump duplicó los aranceles al acero y aluminio de Canadá, el mercado de valores se desplomó. ¿Por qué los mercados financieros han reaccionado así ahora si celebraron, digamos, el triunfo de Trump en noviembre?

Sara: El mercado, yo creo que estaba convencido que Trump no iba a hacer nada de aranceles. Y entonces el mercado seguía como si nada. Hasta el momento en el que el mercado empieza a ver que los aranceles sí se van a convertir en una realidad y el mercado comprende perfectamente que aumentar los precios mediante aranceles es una medida que recesiona la economía, que empequeñece la economía. Y entonces el mercado dice: voy para abajo.

Cuando el mercado se da cuenta que va a haber una pérdida de negocios, una pérdida en empleos, un aumento de precios, ¡pum! responde la bolsa de valores hacia la baja de inmediato. Y la economía, además, depende mucho de la confianza que tienen las personas en las inversiones futuras, sobre todo porque muchas inversiones tardan semanas, meses o incluso años en concretarse. Y entonces ellos esperan que un aviso de un arancel hoy va a tener impacto en cinco años. Desde hoy empiezas a ver el rezago económico. Y desde hoy empiezas a percibir que la economía se empieza a desacelerar.

Silvia: Hemos hablado del efecto dominó de los aranceles, ¿pero cuál es el efecto dominó de que la Bolsa de Valores de Estados Unidos caiga? Y me refiero al resto del mundo.

Sara: Desafortunadamente, a Estados Unidos le da un resfriado y a nosotros pulmonía. Y en Latinoamérica no solamente tenemos el problema de que nuestras bolsas son un poquito más débiles, sino que nuestro tipo de cambio se puede apreciar y nuestras monedas podrían valer menos en un momento dado. Todo esto tiene repercusiones en el bolsillo de las personas que tenemos menos valor en nuestra cartera. El dinero que tenemos vale menos. Y al haber incertidumbre hay menos inversión. Te esperas tantito antes de empezar ese negocio que estabas pensando con tu familia. ¿Sabes qué? No sé. Vamos a esperarnos tantito. Deja el dinero guardado en el banco. ¿Sabes qué? Pues quédate con el trabajo que tienes ahorita, no busques otro. Todo el mundo se empieza a detener. Y ese es más o menos el efecto de lo que pasa no solamente en Estados Unidos, sino en todo el mundo.

Eliezer: Seguro han escuchado en las últimas semanas que ha crecido el miedo de que Estados Unidos esté dirigiéndose hacia una recesión. La definición “oficial” dice que este es un periodo de descenso en la actividad económica. Se mide con meses consecutivos de baja en tres variables: la producción, el empleo y el ingreso real, es decir, la capacidad de compra con los precios actuales.

Sara: Todos los indicadores muestran que la economía no está en una recesión.

Silvia: Ya lo vimos. Hay poco desempleo, y el PIB y el poder de compra siguen aumentando.

Sara: Afortunadamente, estamos en este momento en que la economía se ve muy fuerte. Quién sabe, quizás sí permanezca por otro rato. Quizá estos costos económicos tarden mucho en suceder. Antes teníamos mucha certidumbre: lo que diga la reserva, lo que diga las expectativas, ahí vamos. Pero ahora no, porque esta persona dice cosas erráticas, que se contradicen. Un día dice que sí hay aranceles, otro día dice que siempre no, y este estado de incertidumbre lo único que genera es que en general todos los indicadores se vayan hacia la baja. Entonces, no te sabría decir si va a haber una recesión, cuándo va a darse esta recesión, si tenemos certeza de que va a haber una recesión. No sé, no sé. Pero lo que sí te puedo decir es que uno, espero que no haya una recesión y dos, cualquier escenario que tengamos ahora estamos peor gracias a estos aranceles.

Silva: Bueno, y para cerrar, siento que tengo que preguntarte esto, pero en medio de todo este caos, ¿hay algo que podamos hacer como consumidores para prepararnos para una eventual recesión o lo que pueda venir si sigue esta guerra comercial?

Sara: Sí, sí, ¿cómo no? Me pongo a pensar en pues en mi gente, ¿no? En mi familia, en mi mamá, mis amigos. Hay varias cosas que podemos hacer. Una es buscar alternativas de productos nacionales, buscar alternativas de bienes accesibles, bienes sustitutos. Sirve que apoyamos a otras empresas más pequeñas. Otra es, tratemos de no endeudarnos en dólares si estás en Latinoamérica. Otra es, preveé comprar cosas que probablemente puedan subir de precio, no solamente los aguacates que se nos echan a perder, pero pues probablemente comprar cosas como un auto, quizá antes de que suba de precio. Por supuesto, algo en lo que somos buenísimos, es en reducir gastos innecesarios de inmediato. Gastos superfluos. Pues no hay necesidad. Esperate tantito. Si puedes, paga tus créditos, no debas dinero, porque si las tasas de interés aumentan, entonces vas a estar en un problema. Es mejor tener la menor deuda posible.

Y yo creo que otra cosa que debemos de hacer es contar los unos con los otros, ¿no? En un momento dado, cuando necesites ayuda, pues vamos a necesitar de esa comunidad, de esos amigos, de esa familia y eso nunca está de más.

Silvia: Sara, muchas gracias por tu tiempo.

Sara: Ay, no, pues muchas gracias por preguntarme. A mí la verdad es que me parece muy importante que los latinos en Estados Unidos y en todo Latinoamérica sepamos lo que está pasando y podamos prepararnos y usemos este superpoder de comunidad que tenemos para enfrentar la situación, venga lo que venga.

Nausícaa Palomeque: Este episodio fue producido por mí, Nausícaa Palomeque. Lo editaron Silvia y Eliezer. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido y la música son de Elías González.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Natalia Ramírez, Juan David Naranjo Navarro, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Desirée Yépez y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres abrir el hilo para informarte en profundidad sobre los temas de cada episodio, puedes suscribirte a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

This story from El hilo was produced with the support of Grupo SURA, an investment manager focused on financial services. SURA promotes independent journalism that strengthens democracy in Latin America and contributes to a better-informed citizenship.

Eliezer Budasoff: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia Viñas: And I’m Silvia Viñas.

Donald Trump has only been back in government for two months and a tariff trade war has already broken out.

Archive audio, host: The President of the United States, Donald Trump, announced that he will impose 25% tariffs on steel and aluminum imports.

Archive audio, host: The tariff threat has Mexico and Canada on edge, who have threatened retaliation. China is also preparing for the onslaught.

Archive audio, female host: And promised to take corresponding countermeasures.

Eliezer: Trump is fulfilling one of his campaign promises. He has sold these tariffs as a panacea. He says they’re going to lower the debt, revive the manufacturing sector in the United States. That they’re going to pressure countries like Mexico to stop the flow of fentanyl and migrants.

Silvia: And in the midst of the chaos, the news about announcements, threats and reprisals, it’s easy to get confused, to lose perspective. But the reality is that this trade war has a direct impact on all of us, the consumers. This week, the OECD lowered its estimates for economic growth for this year and next. And Mexico would be the most affected country.

It could enter a recession. The organization predicts that inflation will rise worldwide.

Today, the real cost of Trump’s tariff war. It’s March 21st, 2025.

Silvia: Sara, there’s been a lot of talk about tariffs. It seems like every day there’s a new headline. It’s changing all the time, but we want to understand the most basic thing: What is a tariff?

Sara Ávila: Well, a tariff is a tax levied on goods imported from other countries.

Eliezer: She is Sara Ávila, a Mexican economist and professor at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Sara: For example, let’s say this is a bag that costs 10 dollars. And if you put a 20% tariff on it, when I import this bag from Mexico to the United States, then I have to pay two dollars for this bag. That’s the tariff.

Silvia: And before this tariff war started, we didn’t pay much attention to them, but obviously they existed. So, for example, how did tariffs work between the United States and Mexico?

Sara: We’ve had tariffs in the past, but in recent decades, since I was a child—I’m already 50 years old—so when I was little there were many tariffs. It was very expensive to get candy from the United States, it was a luxury to have backpacks from the United States because we had a lot of tariffs. As time has passed, tariffs have decreased, especially between Mexico, Canada, and the United States, so that now we can sell and buy products among ourselves without paying extra money. So we have cars, computers, bags, backpacks, pencils and avocados, mangoes, pineapples everywhere without paying additional money. So, this way of living has allowed us to have more markets, more business, and more wealth. That’s how it has worked.

Silvia: Now, Trump insists that tariffs won’t raise prices for people, but we want to understand who really bears the cost of tariffs.

Sara: Yes, at first, when you arrive in the country you have to pay your two dollars, right? It doesn’t matter that you take them from your production. Here are the two dollars. However, what will happen is that you’ll probably want to increase the price of your bag. It will no longer cost 10 dollars, but 12.

When it reaches the consumer, the consumer decides whether to buy it or not. If the consumer needs this good or loves this good and wants to keep paying for it, well, it might hurt them in the wallet, but they’ll keep buying it. But there will come a time when some consumers can’t afford it. Some consumers will no longer be interested and some will stop buying it. A small piece of the market will be lost that will no longer buy this product. Therefore, the bag producer will say, you know what? I’m not going to produce as many bags anymore. This loss in production, sales, and purchases of bags is what is called a loss in welfare. And this loss in welfare is tangible. It’s the pineapples that were no longer produced, it’s the mangoes that were no longer harvested. It’s the corn, it’s the steel, it’s everything that was no longer produced and no longer bought and no longer made. It’s businesses that were no longer created, investments that were no longer made, and jobs that were no longer created. This is a loss in social welfare, and society as a whole pays for it. And between who pays for it, whether the consumer or the producer, it will be either the consumer in the tariff country, who still loves this product and will continue to pay for it, or the producer who needs to sell it and will absorb the cost.

Eliezer: Some estimates have been made about the impact of the 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico, and the 10% on China. According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics, this will cause an average American family to spend $1,200 more per year. Estimates that include other trade variables estimate that it could be about $2,000 per year.

Silvia: Most imported products consumed in the United States already pay tariffs, but lower ones. The average is usually 2.5%. That number is important to understand the scale of this commercial crisis. We’re talking about 10%, 25%. Trump even threatened tariffs of 50%.

Eliezer: In addition to the tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China, on March 12th Trump imposed a 25% tariff on all steel and aluminum imports. To all countries.

Sara: It affects Brazil, it affects Mexico, it affects Canada, even Europe, and most countries have responded, China, of course, they have responded with immediate tariffs.

Eliezer: That is, they’ve put tariffs back on the United States. Another affected country in the region is Argentina, whose government is an ally of Trump. 40% of that country’s total aluminum exports go to the United States. And the Argentine steel chamber asked the government to negotiate with the United States to reverse the tariffs.

Silvia: The tariffs on aluminum and steel are important because these metals are used in many products, such as machinery, cars, home appliances, medical devices. Sara explained to us that sometimes the impact begins with one piece and expands to the entire production process. This happens, for example, with cars.

Sara: These are production processes that even have several phases where the screw is produced here, sent to Canada, Canada assembles it, that part is sent here, we put it in the car and then it’s sold in the United States. When you put tariffs, you not only increase the price of the little screw, but probably also the price of the lug nut and the price of the tire and the price of the door. And then this creates a domino effect that in the end the price of a car will become considerably more expensive. That’s why the automotive industry in the United States begged Donald Trump not to do this, and Donald Trump backed down in some cases, right? Because it’s very painful for this industry that was already in trouble, now with higher costs thanks to these tariffs, of course!

Eliezer: Another sector that could be heavily affected is agriculture. If there is no change, the increase in tariffs will take effect on April 2nd.

Silvia: When Trump announced them, he posted a message for farmers on his Truth Social network. I quote: “Get ready to start producing a lot more agricultural product for sale within the United States.” And he finished with “Have fun!”

Eliezer: But farmers are already suffering the impact of these measures. They depend on exports. And China, for example, responded to Trump with tariffs of 10% to 15% on products such as wheat, corn, and pork. This is on top of cuts from the Department of Agriculture and other agencies, which are also directly affecting farmers.

Silvia: And this tariff war, of course, has a direct impact on Latin America as well.

Sara: In reality, we as Latin Americans depend a lot on the U.S. market. A large part of our exports goes to the U.S. market. In general, we produce, of course, agricultural services, agricultural products, avocados, pineapples, grapes.

Eliezer: Colombia exports coffee, bananas, and flowers to the United States; Peru, grapes; Argentina, wine, honey, and soybeans; Mexico, beer, avocados, tomatoes…

Sara: And in any case, as Latin Americans, a tariff war affects us very negatively. All our prices increase tremendously. We have markets of a considerable size, but definitely, we are all much richer when we have a larger market to sell our products to. And by having access to the American market, we can sell our products to them, and they are very happy to buy our products. Now, everyone is happy, right? Us selling and them buying. The instant that barriers are put up to this activity, we lose out and, well, they do too by not having access to products as economical as the ones we provide.

Silvia: These measures impact the labor market and opportunities. Sara emphasized that exporting companies usually provide formal jobs, which generate a certain labor stability.

Sara: The instant that you increase the costs for these companies and they start to suffer losses, then we lose good jobs that go towards informality. And the problem in going towards informality is that we lose all this ability to plan for the future, this ability to have access to credit. This ability to have a strengthening of the financial system. And then we go back to situations that don’t help absolutely anyone.

Eliezer: We’ll be right back.

Silvia: This episode comes with the support of Noticias Sin Filtro, an app that connects you with independent journalism from Venezuela.

Eliezer: Increasingly, access to information in Latin American countries is at risk. Blockades to independent media and restrictions on the use of platforms prevent access to verified and reliable information. And in places like Venezuela, for the vast majority of the population, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to find the news they need.

Silvia: With Noticias Sin Filtro, on your cell phone or tablet, you can access independent sources to stay informed. News from the main independent media in the country, videos, local radio programs, and podcasts, all in one place.

Eliezer: This application is a tool that you can download to any cell phone, made in alliance with independent Venezuelan media so that information is always within your reach.

Eliezer: We’re back on El hilo.

Silvia: Trump has been in office for two months. It feels like it’s been much longer because so many things have happened. Are consumers already feeling the effect of these tariffs?

Sara: Look, in the very short term, not yet, I even went to buy avocados immediately before the price goes up and well, this week it doesn’t affect me yet. This week it’s not going to affect us. Not only that, but the U.S. market has very good indicators at the moment.

Eliezer: It has low unemployment, GDP is growing, interest rates are still low.

Sara: If we didn’t have this tariff threat, we would be better off. And the market in general starts with uncertainty. We don’t know what’s going to happen, and by not knowing what’s going to happen, then investment starts to become smaller. And so, if we’re not perceiving the cost in our pockets at this moment, well it will have to be in the medium or long term. Unfortunately, it’s a real cost that we may not be feeling yet, but sooner or later it will be felt and as it’s obvious that it’s happening, even Trump is saying…

Archive audio, Donald Trump: There will be a little disturbance, but we’re OK with that…

Sara: Ah, well, it’s going to be painful, but it’s worth it. He of course has in his mind objectives that don’t necessarily have to do with the well-being of American citizens, but much less with Latin American citizens, right? It seems that among his objectives is: to have power, to be very popular, and to have a bunch of people telling him that everything he does is very well done.

Unfortunately, the evidence shows that Trump has never been very strategic. Trump has gone bankrupt four times. That tells us that he’s really not very strategic, very intelligent, or very good at business. He’s not. I don’t think Trump has an intelligent strategy for absolutely anything. However, some of his advisors suggest that X, Y, or Z can help increase his level of popularity, increase his power. And he definitely wants the United States to be a superpower and for him to be recognized in history as the president who increased the territory of the United States, who brought back manufacturing, and who was the most loved by all.

Silvia: Trump says he wants to recover the manufacturing industry, the factories. A sector that lost many jobs in the last 40 years. They’ve gone to countries like Mexico or China.

Sara: And so he says, well, I need manufacturing to come back to the United States and therefore I’m going to put tariffs on these manufactures that come from other countries.

Eliezer: For Sara, this doesn’t make much sense. Because in a scenario of low unemployment and deportations of migrant people, it’s not so easy to find workers for factories.

Sara: Well, there are no people willing to do these jobs. So from any point you look at it, all economic experts agree. This doesn’t help the economy of the United States or the economy of absolutely anyone.

Silvia: What other objectives does Trump have with these tariffs and these constant threats to impose more?

Sara: I think he’s using tariff rates more as a threat to make countries do what he needs to be done. But really his objectives are not very well defined. There’s no policy where you say: Look, what he wants is to increase the middle class, beyond the fact that apparently all the strategies he has carried out allow the rich to be richer through fewer taxes, through paying fewer taxes and increasing his power as the leader of the most militarily powerful country. It doesn’t look like there’s any other benefit.

Eliezer: As we’ve seen, in reality, the increase in tariffs will mainly affect the ordinary citizen, because the prices of food and goods they consume daily will rise.

Sara: We’re talking about corn, food, like avocados, fruits, we’re talking about bags, chairs, tables, things with aluminum. These kinds of things are bought by the middle class and the poor class. We’re not increasing the tariffs on luxury yachts, luxury trips. That’s really not affected and it’s very, very curious, isn’t it? that in the long run, well, really who would pay for these would be either the companies that produce these goods or the consumers who consume these goods, right? So, even for the North American market, it’s being a very bad strategy.

Silvia: He says he’s doing this with tariffs to, I don’t know, reduce the flow of fentanyl and the flow of migration from Mexico, right? To bring back these jobs that have gone elsewhere and reduce the debt. But is it working for him? Or maybe it’s too early to see that.

Sara: Definitely a tariff policy is not going to help him reduce the debt. It’s not going to help him improve the well-being of North American consumers. It’s going to help him increase prices, it’s going to help him decrease economic growth, it’s going to help him protect a manufacturing sector, probably, that no longer exists. And here I just want to tell you how things are. Let’s say, chronologically, countries, let’s say the poorest ones, dedicate themselves to agriculture, as they grow economically they dedicate themselves to manufacturing, like the United States was. In an era when many workers worked in factories and had well-paid jobs. But as the economy grows and, let’s say, a family becomes richer, they’ve already bought all the mansions they could, they’ve already bought all the cars they could, they’ve already bought all the clothes they could. There’s already a limit. What do you do? You buy a good restaurant, a trip, a service. It’s a service economy. The gringo economy, the North American economy, is dedicated to services because that’s what yields the most. And for some strange reason, Trump wants to return to manufacturing. It doesn’t make any sense. Probably he wants to appeal to this base of Americans who yearn for this past of factories, of people who worked with their hands and produced cars and furniture. That’s over and even if you go back to doing that, it’s a recession to the past, to less productive things, to less valuable things. There’s no point. Someone has to tell him that this doesn’t make sense. And he’s convinced that by returning to this, this whole sector will resurge. This whole sector will regain purchasing power. And that’s not true.

Eliezer: Let’s take another break, and when we return, Sara explains the market’s reaction to Trump’s tariffs, and how we can navigate economic uncertainty. We’ll be right back.

Eliezer: We’re back on El hilo.

Silvia: When Trump doubled the tariffs on steel and aluminum from Canada, the stock market plummeted. Why have financial markets reacted this way now if they celebrated, let’s say, Trump’s victory in November?

Sara: The market, I think, was convinced that Trump wasn’t going to do anything with tariffs. And so the market continued as if nothing had happened. Until the moment the market begins to see that the tariffs are going to become a reality and the market perfectly understands that increasing prices through tariffs is a measure that recessions the economy, that shrinks the economy. And then the market says: I’m going down.

When the market realizes that there’s going to be a loss of business, a loss in jobs, an increase in prices, boom! the stock market responds downwards immediately. And the economy, moreover, depends a lot on the confidence that people have in future investments, especially because many investments take weeks, months, or even years to materialize. And so they expect that a notice of a tariff today will have an impact in five years. From today you start to see the economic lag. And from today you start to perceive that the economy begins to slow down.

Silvia: We’ve talked about the domino effect of tariffs, but what is the domino effect of the U.S. Stock Market falling? And I’m referring to the rest of the world.

Sara: Unfortunately, the United States gets a cold and we get pneumonia. And in Latin America we not only have the problem that our stock markets are a little weaker, but that our exchange rate can appreciate and our currencies could be worth less at a given moment. All this has repercussions on people’s wallets, we have less value in our wallets. The money we have is worth less. And when there’s uncertainty there’s less investment. You wait a bit before starting that business you were thinking about with your family. You know what? I don’t know. Let’s wait a bit. Leave the money in the bank. You know what? Well, keep the job you have right now, don’t look for another one. Everyone starts to stop. And that’s more or less the effect of what happens not only in the United States, but throughout the world.

Eliezer: You’ve surely heard in recent weeks that the fear has grown that the United States is heading towards a recession. The “official” definition says that this is a period of decline in economic activity. It’s measured with consecutive months of decline in three variables: production, employment, and real income, that is, purchasing power with current prices.

Sara: All indicators show that the economy is not in a recession.

Silvia: We’ve already seen it. There’s little unemployment, and GDP and purchasing power continue to increase.

Sara: Fortunately, we are at this moment when the economy looks very strong. Who knows, maybe it will remain that way for a while longer. Maybe these economic costs will take a long time to happen. Before we had a lot of certainty: what the reserve says, what the expectations say, there we go. But now no, because this person says erratic things, that contradict each other. One day he says yes to tariffs, another day he says no, and this state of uncertainty only generates that in general all indicators go down. So, I couldn’t tell you if there’s going to be a recession, when this recession is going to occur, if we’re certain that there’s going to be a recession. I don’t know, I don’t know. But what I can tell you is that one, I hope there’s no recession and two, whatever scenario we have now, we’re worse off thanks to these tariffs.

Silva: Well, and to close, I feel like I have to ask you this, but in the midst of all this chaos, is there anything we can do as consumers to prepare for a possible recession or whatever may come if this trade war continues?

Sara: Yes, yes, of course! I start thinking about, well, my people, right? My family, my mom, my friends. There are several things we can do. One is to look for alternatives of national products, look for alternatives of accessible goods, substitute goods. It helps that we support other smaller companies. Another is, let’s try not to get into debt in dollars if you’re in Latin America. Another is, plan to buy things that might go up in price, not just avocados that go bad on us, but probably buying things like a car, maybe before the price goes up. Of course, something we’re very good at is reducing unnecessary expenses immediately. Superfluous expenses. Well, there’s no need. Wait a bit. If you can, pay your credits, don’t owe money, because if interest rates increase, then you’re going to be in trouble. It’s better to have as little debt as possible.

And I think another thing we should do is count on each other, right? At some point, when you need help, well, we’re going to need that community, those friends, that family, and that’s never a bad thing.

Silvia: Sara, thank you very much for your time.

Sara: Oh, no, well, thank you very much for asking me. The truth is that I think it’s very important for Latinos in the United States and throughout Latin America to know what’s happening and to be able to prepare and use this superpower of community that we have to face the situation, come what may.

Nausícaa Palomeque: This episode was produced by me, Nausícaa Palomeque. It was edited by Silvia and Eliezer. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. The sound design and music are by Elías González.

The rest of the El hilo team includes Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Natalia Ramírez, Juan David Naranjo Navarro, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Desirée Yépez, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask you to join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to open the thread to inform yourself in depth about the topics of each episode, you can subscribe to our newsletter by entering elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it every Friday.

You can also follow us on our social networks. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook, and Threads. You can find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share the episodes.

Thanks for listening.