Brasil

Amazonía

Yawanawá

Biraci Nixiwaka

Dom Phillips

Este episodio fue producido con el apoyo del Amazon Rainforest Journalism Fund en colaboración con el Pulitzer Center.

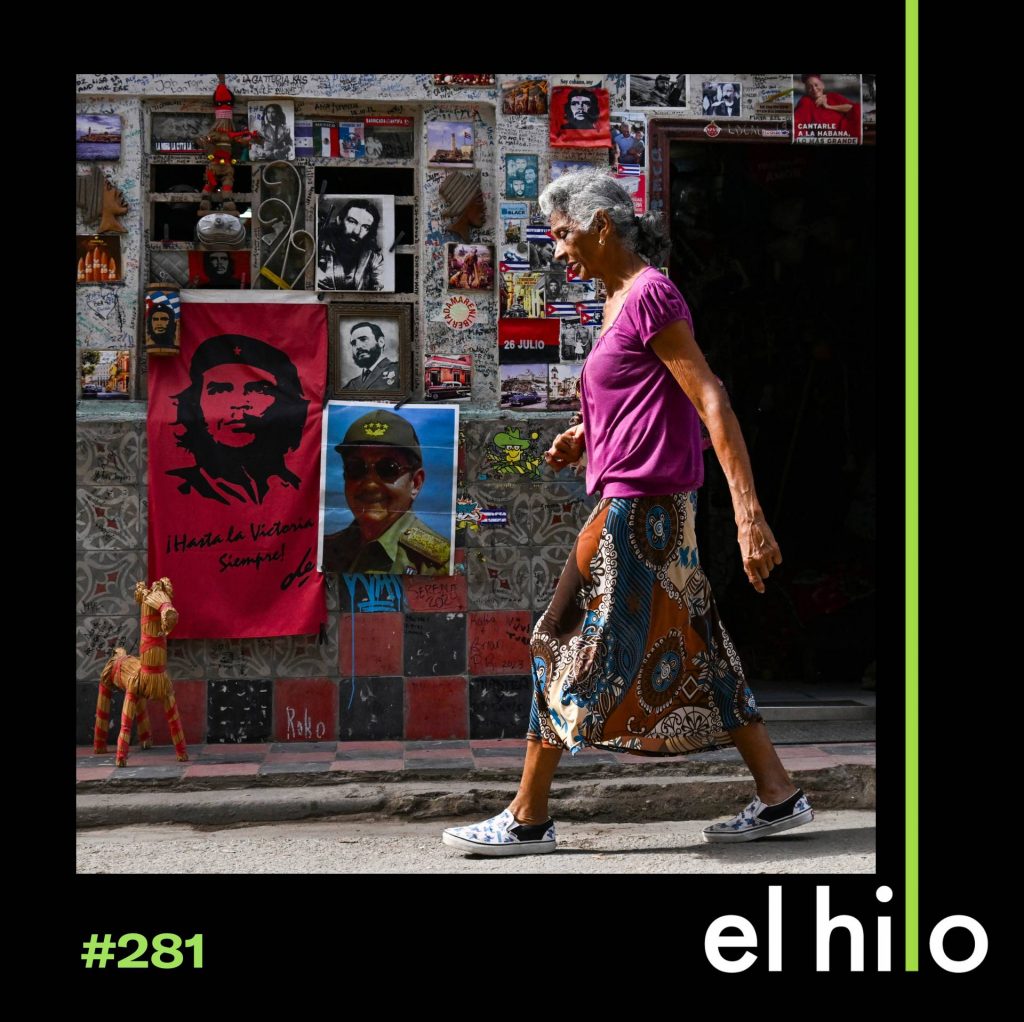

El periodista británico Dom Phillips tenía planeado un viaje a la comunidad indígena yawanawá para buscar respuestas a la crisis de la Amazonía. Pero nunca llegó. En junio de 2022 fue asesinado junto al indigenista Bruno Pereira. Phillips estaba documentando historias de resistencia y esperanza en la Amazonía brasileña frente a las políticas extractivistas de Jair Bolsonaro. Iba a entrevistar al cacique Biraci Nixiwaka, conocido como Bira, una figura histórica del movimiento indígena. Con el periodista brasileño Felipe Milanez viajamos a la Amazonía para contar la historia de los yawanawá y hacer la entrevista que Phillps no pudo.

Créditos:

-

Reportería y producción

Eliezer Budasoff, Felipe Milanez -

Edición

Silvia Viñas -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción en redes sociales

Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Elías González -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

Fotografía

Felipe Milanez

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Eliezer: Hola, esta semana estamos fuera, así que queremos compartir un episodio que reportamos hace un tiempo, pero que toca un tema que va a ser central este año: nuestra relación con la selva tropical más grande del mundo, la Amazonía, donde se va a hacer en unos meses la COP30, la Conferencia de Naciones Unidas sobre Cambio Climático. Volvemos la semana que viene con un episodio nuevo.

Silvia: Esta historia fue producida con el apoyo del Amazon Rainforest Journalism Fund en alianza con el Pulitzer Center.

Audio cantos yawanawá.

Eliezer: Es un viernes de finales de julio, cerca de las 2 de la tarde. En la Aldea Sagrada de los yawanawá, un pueblo nativo de la Amazonía brasileña, unas 20 mujeres se han reunido a ensayar cantos para una ceremonia que tendrá lugar en unos días. Están sentadas en círculo debajo de una cabaña enorme, sin paredes, que hace rebotar sus voces en el techo y las multiplica, las proyecta…

Audio cantos yawanawá.

Eliezer: Estoy en esta aldea por un doble homicidio, por la historia que no llegó a contar el periodista británico Dom Phillips, que fue asesinado en la Amazonía en 2022 junto al indigenista Bruno Pereira. Pero, para entender por qué viajamos hasta acá, por qué Dom Phillips quería escribir sobre esta comunidad y su cacique, es importante saber esto: los yawanawá adoran la música. Es parte esencial de su vida colectiva. Como otros pueblos de esta región, la tierra indígena del río Gregorio, en el estado brasileño de Acre, la música que hacen es melódica. Lo principal son los cantos, que tienen una función espiritual. Pero en este caso, también son el símbolo de una lucha política…

Audio cantos yawanawá.

Silvia: Durante una década, aproximadamente, los yawanawá tuvieron prohibido cantar. El pueblo había sido sometido por misioneros evangélicos que les impedían practicar sus rituales, hacer fiestas o hablar su lengua, y permitían que los caucheros los explotaran como mano de obra semiesclava. Sus tradiciones y conocimientos estaban desapareciendo.

Pero hace 40 años, un joven de 18 años que se había ido de la comunidad volvió para expulsar a los misioneros.

Bira: Eles convenceram muitos de nossos povos indígenas da Amazônia e das América, foi um sistema muito cruel, o sistema mais ridículo. Em nome da paz, em nome de Deus, em nome da justiça divina…

Eliezer: El hombre que están escuchando es aquel joven, el que organizó la expulsión de los evangélicos de su comunidad. Su nombre es Biraci Brasil Nixiwaka y la gente le dice Bira. El cacique Bira es una figura histórica del movimiento indígena brasileño. Dice que los misioneros convencieron a muchos pueblos en la Amazonía y en América, pero que fue un sistema muy cruel, el más ridículo… en nombre de la paz, de Dios, de la justicia divina.

Bira: Como é que uma pessoa está falando de paz e de amor, de cura, de salvação, critica uma cultura, explora um povo tradicional, oprime as nossas tradições.

Silvia: Cómo es que una persona que está hablando de paz y amor, de curar, de salvación, dice Bira, critica a una cultura, explota a un pueblo tradicional y oprime sus tradiciones…

Desde que era adolescente, Bira lideró la lucha por los derechos de su pueblo, por el reconocimiento de sus territorios y por su autonomía. Primero fue un dirigente político, pero entendió que tenía que ser también un líder espiritual. Tenían que reconstruir su cultura y sus tradiciones, recuperar el conocimiento y el orgullo de ser quienes eran. Entonces empezó un largo proceso que llevó décadas de trabajo, pero que ha convertido a los yawanawá en un ejemplo de resistencia cultural y de estrategia política a nivel global. Por eso el periodista Dom Phillips quería entrevistarlo. Y le pidió el contacto a su colega brasileño Felipe Milanez. Este es Felipe:

Felipe Milanez: Dom estaba haciendo un libro sobre cómo salvar la Amazonía en uno de los periodos más violentos de la historia de Brasil, que fue el gobierno de Bolsonaro. Tanta tragedia, tanta destrucción, aumento de la tasa de deforestación, minería ilegales, asesinatos, amenazas de muerte y venir a Acre para Dom también era un momento de esperanza.

Audio cantos yawanawá.

Silvia: Felipe es profesor y periodista, desde hace años investiga la cultura y las luchas de los pueblos indígenas de Brasil. Así conoció al cacique Bira y la historia de los yawanawá. Felipe es un viejo amigo de Bira y también era amigo de Dom Philips, y puso en contacto a los dos, porque para su libro, Philips quería mostrar que había otras formas de habitar esa Amazonía que estaba siendo arrasada. Pero nunca llegó a entrevistar al cacique.

Felipe: Su último viaje iba a ser acá, donde estamos, en la aldea sagrada de los yawanawá. Y Bira lo estaba esperando a él cuando supo de la tragedia.

Eliezer: Por eso estamos acá, un año después de la muerte de Dom Philips y Bruno Pereira junto al cacique Bira, escuchando a un grupo de mujeres que ensayan los cantos para una ceremonia, mientras algunos habitantes se van acercando como hipnotizados. Los rituales y la música por la que hoy son conocidos los yawanawá son parte de la historia que quería contar Dom Phillips, y que vamos a tratar de contar con Felipe en este episodio. Porque la estrategia de resistencia de la comunidad también tiene que ver con esto: con haber logrado recuperar, junto con su cultura, la posibilidad cotidiana de la belleza.

Audio cantos yawanawá.

Eliezer: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Estudios. Soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: Y yo soy Silvia Viñas.

Hoy, una forma de salvar la Amazonía: la lucha del pueblo yawanawá y la mirada del cacique Biraci Nixiwaka, la entrevista que no pudo hacer Dom Phillips.

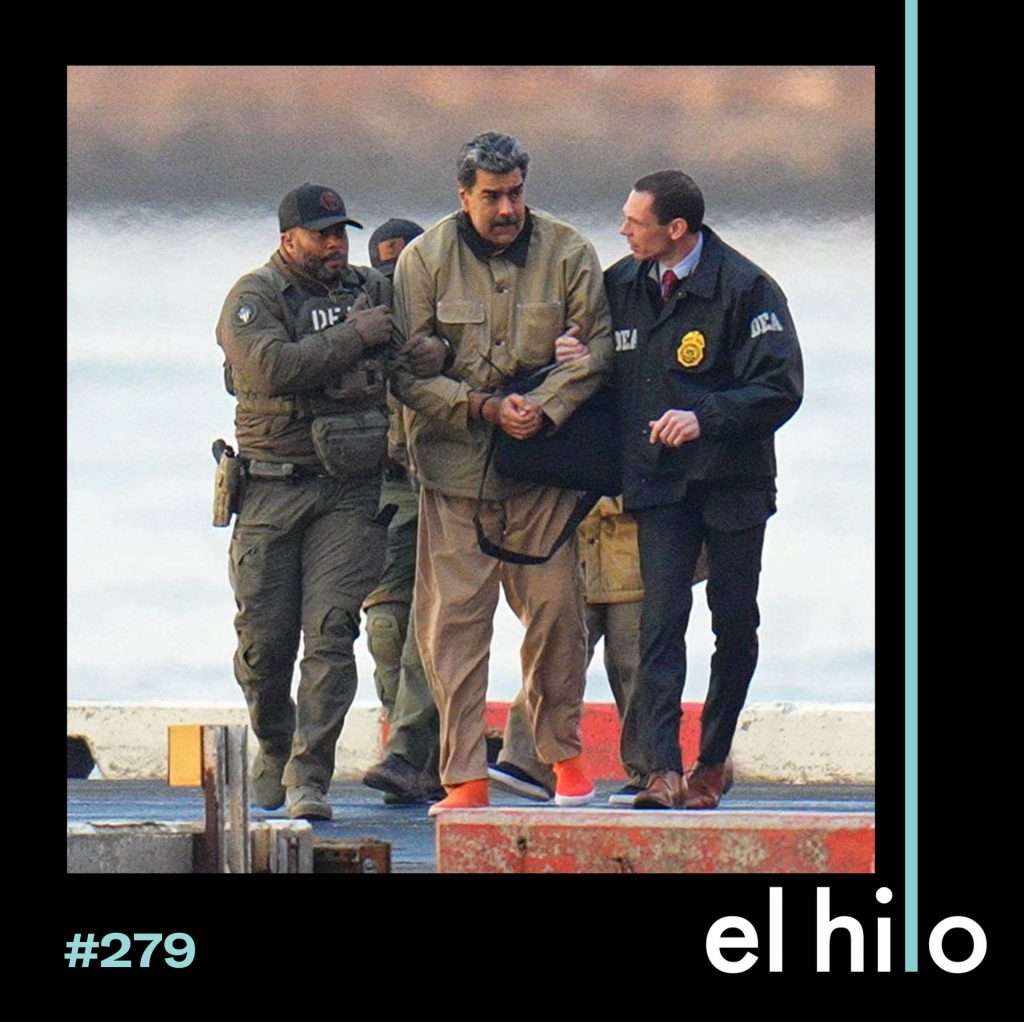

Silvia: El periodista Dom Phillips y el indigenista Bruno Araujo Pereira fueron asesinados en junio de 2022, durante los últimos meses del gobierno de Jair Bolsonaro. Fue en el Valle de Yavarí, uno de los territorios indígenas más extensos de Brasil, cerca de la frontera con Perú.

Reportera: La policía federal de Brasil confirma que los restos encontrados en la amazonía brasileña pertenecían al periodista británico Dom Phillips.

Reportero: Fueron asesinados violentamente por conexiones criminales que el Estado brasileño, bajo el gobierno de Bolsonaro, no combatió.

Reportera: Un pescador furtivo detenido por la policía confesó el crimen y señaló el lugar donde estaban los cuerpos.

Activista: Justiça seria a continuidade do trabalho de Bruno…

Reportera: Justicia sería la continuidad del trabajo de Bruno, de la vida de Bruno, de la vida de Dom Phillips que estaban en el bosque junto a nuestros territorios para la defensa y protección de nuestras vidas.

Eliezer: Como contamos antes, Phillips estaba haciendo un libro sobre el futuro de la Amazonía, amenazada por una violencia y una voracidad de intereses que no eran nuevos, pero que habían sido cebados y liberados por el gobierno de Bolsonaro.

Felipe: Bolsonaro tenía como inspiración de su gobierno, el gobierno de la dictadura militar, que fue el gobierno que empezó la invasión y la destrucción de la Amazonía en 1970. Bolsonaro ha promocionado la explotación total e ilegal de las fronteras económicas de la Amazonía: apoyó al crimen de la deforestación, al crimen de la minería…

Silvia: Felipe había conocido a Dom Phillips, justamente, por la preocupación que ambos compartían sobre lo que pasaba con la selva tropical más grande del mundo y sus habitantes.

Felipe: Yo conocí a Dom por su trabajo en Amazonia. Empecé a leer los trabajos de Dom y nos aproximamos por redes sociales, intercambios de información y luego empezamos a charlar. Inicialmente, yo como fuente de Dom.

Eliezer: Phillips había llegado a Brasil en 2007 como periodista cultural dedicado a la música, pero con el paso del tiempo la Amazonía se convirtió en su interés principal. Publicaba sobre eso en medios como The Guardian y el New York Times. Algunos años antes de su asesinato, se había mudado a vivir con su esposa a Salvador de Bahía, en el norte del país, donde vive Felipe. Esa cercanía terminó por sellar su amistad, que se fortaleció durante la pandemia.

Felipe: Íbamos a la playa y hacíamos deportes en la playa en estas lindas playas de Salvador de la magnífica Bahía, y mientras remábamos por la bahía, charlábamos sobre la Amazonía, intercambiábamos ideas. Dom me hacía preguntas desde mi experiencia en la Amazonía y yo aprendía mucho con Dom a escuchar más a la gente, a hablar menos también, ¿sabe?

Silvia: Felipe cuenta que, además, aprendió a ver su país a través de los ojos de Phillips, alguien que venía de una clase obrera de las afueras de Liverpool, que conocía la historia colonial de su país y los horrores de la monarquía, y pensaba en un mundo más igualitario. A los dos les interesaban las experiencias de resistencia de los pueblos indígenas. Felipe conocía ese mundo desde hacía casi 15 años, cuando empezó a trabajar como periodista para la Funai, la Fundación Nacional del Indio de Brasil.

Felipe: Yo aprendí como servidor del estado de Brasil haciendo un trabajo en defensa de los pueblos indígenas. Y ahí, cuando trabajé en la Funai, yo conocí a los grandes líderes indígenas en Brasil. Descubrí un país mucho más diverso, mucho más encantador que el país que existía para mí antes de trabajar en la Funai.

Eliezer: En la Funai, Felipe aprendió de los indigenistas más veteranos de Brasil, los sertanistas, que protegían los derechos de los pueblos indígenas. Uno de ellos, que había trabajado con tribus aisladas y con comunidades en el estado de Acre, le presentó al cacique Bira, que en ese momento estaba peleando para que ampliaran los límites del territorio de los yawanawá.

Felipe: Fue una amistad muy rápida por mi admiración, por la simpatía de Bira, que es una persona que es muy abierta y sabe reconocer potenciales aliados siempre y de mi parte una admiración, un encantamiento que yo tengo con esta generación que hizo la revolución en Brasil en los movimientos indígenas en los 80.

Silvia: En los 80, Bira había logrado el primer reconocimiento de tierras indígenas en el estado de Acre, cuando el país todavía estaba en dictadura. Ese fue el punto de partida para que pudieran expulsar de sus territorios a los caucheros y a los misioneros.

Eliezer: Felipe me contó una frase que siempre le decía el indigenista que le presentó por primera vez al cacique Bira, el que le habló de las luchas de los yawanawá y otros pueblos en el estado de Acre:

Felipe: Los peores tipos que hay son los mineros, los madereros y los misioneros, pero de todos, los peores son los misioneros, porque hasta el fin van a intentar invadir a los territorios indígenas y destruir por adentro el territorio indígena.

Eliezer: Felipe me explicó que los misioneros habían llegado con la excusa de hacer un trabajo humanitario, supuestamente para velar por la salud y la educación de las comunidades, pero que en realidad solo les interesaba traducir la Biblia y convertir a los indígenas para explotarlos. Los manipulaban a cambio de darles remedios, y había misioneros que estaban aliados a una empresa que se llama Paranacre, que esclavizaba a los yawanawa. La compañía había comprado una zona de plantaciones de caucho para extraer madera y explotar la tierra para la ganadería… Y Bira lideró la lucha para expulsarlos del territorio y recuperar sus tierras.

Silvia: Bira fue compañero de luchas de Chico Mendes, el activista ambiental asesinado por rancheros que se convirtió en un símbolo mundial, y de Marina Silva, la actual ministra de Medio Ambiente de Brasil, que también eran del estado de Acre. El cacique fue parte del grupo que en los ochenta creó la Alianza de los Pueblos de la Floresta, que reunió a comunidades indígenas y ribereñas de la Amazonía con caucheros. Llegó a ser candidato a diputado. Pero cuando Felipe lo conoció, Bira estaba en medio de un proceso de reconstrucción de su cultura y sus tradiciones.

Felipe: Los yawanawa ya tenían… ya eran reconocidos por su gran creatividad, por estar haciendo cosas nuevas, recibir gente muy conocida en el mundo, actores, ambientalistas.

Eliezer: El actor Joaquín Phoenix, por ejemplo, los visitó a comienzos de los 2000 para grabar un documental. Este mes, Leonardo DiCaprio estuvo con Bira en un evento. El actor está apoyando un proyecto de arte digital en el que están participando los yawanawa, que han tejido redes en todo el mundo. Entre otras cosas, hace años hicieron un acuerdo con la empresa de cosméticos Aveda, de Estados Unidos, a la que proveen de achiote o urucum, un pigmento que ellos usan para pintarse el cuerpo.

Felipe: Un pueblo muy creativo, con muchas ideas, de mucha autonomía. Y que estaban manejando la defensa del territorio, la defensa de la cultura con artes, músicas, festivales y con mucha fuerza espiritual.

Silvia: En el año 2000 crearon el festival anual Mariri yawanawa, que busca preservar la cultura y las tradiciones del pueblo. Reúne a 17 aldeas y dura alrededor de una semana. Hay cantos, bailes, ceremonias, juegos… y es uno de los pocos festivales indígenas que está abierto a un número limitado de turistas.

Eliezer: Felipe fue por primera vez a visitar a los yawanawá en 2007, invitado por Bira y cautivado por su estrategia de liderazgo, que había comprendido que la dimensión espiritual de su pueblo era una herramienta política poderosa.

Felipe: Fue un momento de conocer las historias por la primera vez, desde su propia palabras, de la violencia de la dictadura militar en Brasil y en Acre. Y también fue cuando yo escuché desde Bira su testimonio sobre la violencia cultural de los misioneros, sobre el etnocidio, sobre el racismo, y sobre cómo un líder tomó conciencia de esta forma de opresión, intentó movilizar a su pueblo y desde esa su insurgencia buscar libertad y autonomía.

Silvia: Los años siguientes Felipe volvió a ir a las tierras de Bira, aprendió de su historia y de los chamanes más antiguos del pueblo. Y trabajó con el cacique para plasmar parte de su experiencia en un texto.

No es extraño, entonces, que Felipe hablara del cacique Bira y de los yawanawá con su amigo Dom Phillips, que estaba documentando historias de resistencia y esperanza en la Amazonía frente a las políticas de Bolsonaro… un gobierno inspirado en la dictadura, que alentaba la explotación indiscriminada de la selva y compartía la mirada racista de los misioneros evangélicos sobre la cultura indígena.

Eliezer: Para entonces, cuando hablaban de sus experiencias y hacían deportes juntos en las playas de Bahía, Felipe ya estaba dedicado casi por completo al trabajo académico y docente. A finales de 2021, mientras hacía una estadía para un posdoctorado en Nueva York, recibió un mensaje de Phillips, que le pedía si le podía pasar el teléfono de Bira.

Felipe: En este momento yo ya no era como una fuente de Dom, pero como un compañero de intercambiar ideas. Y yo hice el contacto con Bira. Yo hablé con Bira y pasé los contactos de Bira a Dom. Y Dom empezó a llamar, a ver, a intercambiar mensajes con él también para organizar su misión en Acre, de visitar a los asháninka y a los yawanawa como dos pueblos que hoy son ejemplo de defensa del territorio de la cultura. Son ejemplos globales de cómo se puede desarrollar bien una comunidad, vivir bien y proteger a la naturaleza para las futuras generaciones.

Silvia: A principios de 2022, mientras intercambiaban mensajes, Phillips le contó a Felipe que ya tenía fechas para su viaje.

Felipe: Dom había organizado de hacer un viaje entre mayo y junio el año pasado entre el Valle de Javari y Acre.

Eliezer: Primero fue a visitar a los asháninkas, un pueblo indígena mayoritario en Perú, con una población pequeña en el estado de Acre, donde están también las tierras de los yawanawá.

Felipe: Después de los asháninkas. Iba a venir a visitar a Bira, pero Bira tuvo que hacer un retiro espiritual y postergó el viaje de Dom para un mes más.

Silvia: Así que Dom fue al valle de Yavarí, para entrevistar a los indígenas que trabajaban con el indigenista Bruno Pereira. El plan era que después de eso regresaría al estado de Acre para entrevistar a Bira. Pero nunca llegó. El 5 de junio de 2022, cuando viajaban por el Valle de Yavarí para documentar el trabajo que hacía Bruno con pobladores ribereños e indígenas para proteger el territorio de la invasión de mafias y el narcotráfico, ambos desaparecieron. Dos días después, Felipe le escribió por última vez al teléfono de Dom Phillips.

Felipe: Desafortunadamente, el último mensaje que yo le envío, algo como una esperanza que intentaba mantener en el corazón. 7 de junio de 2022: “Torcendo para estar tudo bem consigo, Dom. Muito.”

Eliezer: Es decir: haciendo fuerzas para que esté todo bien contigo. El mensaje nunca fue recibido.

Mientras seguían desaparecidos, el presidente Jair Bolsonaro dijo que el periodista británico era mal visto en la región porque hacía muchos reportajes contra los mineros ilegales y la cuestión ambiental.

Archivo, Jair Bolsonaro, expresidente de Brasil: esse inglês, ele era malvisto na região porque ele fazia muita matéria contra garimpeiro e questão ambiental…

Silvia: También dijo que se habían ido a meter solos en un área inhóspita, sin seguridad. En realidad, Bruno Pereira conocía muy bien la zona. Había sido coordinador de los pueblos indígenas en aislamiento voluntario en la Funai, desde donde trabajó para expulsar a los mineros ilegales, y el Gobierno de Bolsonaro lo sacó de su cargo. En su lugar, irónicamente, nombraron a un pastor que había trabajado como misionero evangelista en la Amazonía.

Eliezer: Diez días después de la desaparición de los hombres, un pescador detenido por la policía confesó que había participado del asesinato, y llevó a los investigadores adonde habían enterrado los restos.

Silvia: Después de la pausa, la entrevista que no pudo hacer Dom Phillips. Ya volvemos.

Silvia: Queremos compartir con ustedes una excelente noticia: Esta semana cualquier donación que recibamos será duplicada por NewsMatch, una beca para impulsar medios sin ánimo de lucro como es El hilo. Quiere decir que si te unes a nuestras membresías con cualquier monto antes del lunes, recibiremos el doble. ¡Tu apoyo tendrá el doble de impacto!

Eliezer: Hay distintas maneras de apoyar a El hilo; escuchando y recomendándolo a tus amigos funciona. Pero este año, dados los retos financieros que enfrenta el periodismo y particularmente nuestros podcasts, hemos venido con urgencia a pedirles que si pueden, hagan una donación. Nos servirá para preservar nuestro periodismo y seguir explicando la complejidad de América Latina cada viernes.

Silvia: Queremos seguir haciendo episodios como el de hoy y como los 50 que produjimos este año. Si tú también quieres seguir escuchándolos, aprovecha esta oportunidad que nos da NewsMatch y apóyanos con una donación. Ve a elhilo.audio/donar

Gracias desde ya.

Sonido del aeropuerto de Brasilia.

Eliezer: Estoy en el aeropuerto de Brasilia, donde quedamos en encontrarnos con Felipe para tomar el único vuelo diario que hay hacia la ciudad de Cruzeiro do Sul, en el estado de Acre. No existe una forma fácil de llegar a las tierras de los yawanawá, no importa si uno llega desde otro país o de otro estado de Brasil. Desde la capital del país, volamos cinco horas hasta llegar a Cruzeiro. Aterrizamos a medianoche, descansamos un poco y nos subimos a un auto.

Felipe: Ahora son cinco y medio de la mañana, despertándonos, todavía no hay luz afuera, estamos tomando la carretera hasta el puerto que está… que se llama San Vicente, donde la carretera cruza el río Gregorio.

Eliezer: Después de casi tres horas por carretera llegamos a un puerto pequeño sobre el río Gregorio. Subimos a un bote y navegamos por siete horas más, hasta que finalmente llegamos.

Felipe: !Iuju! Boa, meu cara. Acabamos de llegar Aldea Sagrada de los yawanawá, tres y media de la tarde. Qué lindo, qué lindo…

Eliezer: Los yawanawá no son una tribu numerosa. Tienen una población de alrededor de 1,200 habitantes, casi todos distribuidos en comunidades en los márgenes del río Gregorio. La Aldea Sagrada, donde estamos nosotros, es pequeña, pero es el lugar donde suelen recibir a los visitantes.

Felipe: Que emoção

Bira: Tudo bom, querido? bem-vindo

Felipe: Saudades…

Bira: Quanto tempo

Felipe: Aqui de volta na aldeia sagrada

“Una verdadera aldea global”, dice el cacique Bira, que vive aquí con parte de su familia, después de darnos la bienvenida y abrazar a Felipe.

Eliezer: Cuando llegamos, el pueblo se estaba preparando para recibir a unas 30 mujeres de todo el mundo que venían a hacer un retiro espiritual con Putany, la esposa de Bira, primera chamana mujer del pueblo. También esperaban un pequeño grupo de técnicos de una ONG que está ayudando a las comunidades a geolocalizar recursos y dinámicas de sus territorios. Bira nos mostró donde íbamos a dormir, una cabaña con techo de paja y postes de madera para colgar las hamacas. Nos llevó a recorrer la aldea y nos dijo que al otro día lo buscáramos para hacer la entrevista.

La mañana siguiente, antes de ir a buscar al cacique, le pedí a Felipe que describiera dónde estábamos y lo que se veía desde ahí.

Felipe: Estamos en la hamaca hablando mientras escuchamos a Bira desde las 04:00 de la mañana reunido, el jefe Nixiwaká estuvo desde las 04:00 reunido con la comunidad, organizando las tareas, distribuyendo los trabajos, contando historias. Aquí donde estamos es esta es una parte alta de la aldea en frente al río Gregorio, donde se puede ver el bosque, no, tan lindo, los árboles de 30, 40 metros, enfrente de nosotros. Eso es parte de la vida de los yawanawa, la posibilidad cotidiana de la belleza, de la estética, ¿no? La estética de la aldea, la estética de las ropas, de las pinturas, de la vida. Y la admiración que ellos tienen con el bosque, con la floresta amazónica.

Eliezer:A media mañana fuimos a buscar a Bira a su casa. Salimos de ahí acompañados por un hijo y un sobrino del cacique, y empezamos a caminar hacia el bosque. A medida que nos alejábamos del centro de la aldea iban apareciendo paneles solares, otras casas aisladas, lugares para hacer retiros espirituales, un cementerio sagrado, cultivos de hierbas medicinales, una plantación de ayahuasca…

Bira: Aldeia Sagrada, daqui do yawanawá, tem o maior plantio de folha do caiuá rainha para fazer ayahuasca. Maior da Amazônia está aqui.

Eliezer: Bira nos aseguró que ellos tenían el mayor cultivo de plantas para hacer ayahuasca, una de las principales medicinas tradicionales de los pueblos indígenas. Los yawanawá son conocidos por su experiencia ancestral en el uso de la ayahuasca, y el cacique ha participado de encuentros mundiales sobre la utilización de psicodélicos. Más adelante vamos a hablar de esto, pero en ese momento seguimos hasta llegar a un claro en el bosque, nos sentamos sobre unos troncos, y Felipe comenzó a hablar.

Primero le contó a Bira sobre sus conversaciones con Dom Phillips y el proyecto de libro que él estaba escribiendo, lo que estaba buscando…

yawanawá naquele momento, sobre tudo tão violento no Brasil. Ele via como um lugar de esperança onde as coisas estavam dando certo…

Eliezer: Y le contó que, una de las razones por las que estábamos ahí era porque queríamos saber qué pensaba responderle a Phillips, que iba a preguntarle cómo salvar la Amazonía. Bira empezó entonces una larga reflexión, en la que habló de sus ideas, de los hechos que habían dado forma a su mirada, de aquello que los había llevado a ser lo que eran hoy.

Bira: Eu vi que uma das coisas que a sociedade branca tem enfraquecido é quando eles dividem a gente e quando ele enfraquece a organização social, cultural e espiritual dos nossos povos.

Eliezer: Bira dijo que él había visto que la sociedad blanca los había debilitado cuando los dividía, cuando socavaba la organización de sus pueblos. Y que por eso él siempre se preocupó de fortalecer su casa, de que estuvieran unidos internamente para que pudieran enfrentar colectivamente los desafíos. Dijo que el sistema que los blancos habían creado para invadir y explotar sus tierras, con el argumento de que los pueblos indígenas retrasaban el desarrollo, era un sistema fracasado.

Bira: A economia não trouxe um bem social para a humanidade, pelo contrário, também tem criado mais violência, muitas guerras, aquecimento global, mais pobreza para a humanidade. Cada vez mais nós temos gente passando fome no mundo inteiro. Então, como é que vocês estão falando que nós estamos? Somos um atraso se vocês têm se deteriorado cada vez mais a sociedade de vocês.

Eliezer: Para Bira, y esto es algo que va a transmitir de varias maneras, es evidente que la que necesita ayuda es la sociedad occidental. Bira dijo que la tarea que ellos hacen de mantener la selva en pie es fundamental para la humanidad, pero no puede ser una tarea aislada. Que hay que hacer alianzas globales. Crear un sistema paralelo al actual, que solo concibe la Amazonía como una tierra para arrasar y exprimir.

Bira: A gente tem que, a gente tem que construir algo paralelo a esse sistema, mas sem excluir o outro, né? É possível a gente usar hoje a tecnologia também participar da economia ao mesmo tempo preservando a floresta, mantendo a nossa cultura, mantendo nossas famílias, vivendo na aldeia em paz.

Eliezer: Mantener la selva, dice Bira, no significa rechazar los adelantos tecnológicos, pero implica entender lo trascendente que es la cultura y el conocimiento de los pueblos originarios, que son los únicos que conocen el lenguaje de la naturaleza.

Bira: Nós povos indígenas, nós povos originários, somos o único povo do planeta que sabemos falar essa linguagem da natureza, falar a língua, a linguagem dos pássaros, a linguagem das árvores, a linguagem dos animais, a linguagem dos peixes. Todo movimento do astro, do vento, do sol, da lua, das estrelas.

Eliezer: Dice que ellos conocen las plantas medicinales, las plantas sagradas, sus nombres… que tienen una comunicación con su mundo espiritual.

Bira: A gente pode traduzir isso para a humanidade. Mas como nós vamos fazer isso? Nós somos excluídos do sistema.

Eliezer: No es posible traducir el conocimiento que ellos tienen sobre la naturaleza, explica Bira, si son excluidos del sistema.

Felipe le preguntó a Bira por Bolsonaro, por la línea que podía unir lo que había pasado con la Amazonía durante su gobierno y la lucha de los yawanawá para liberarse de los misioneros y de la explotación de sus tierras.

Bira: Em toda a minha vida o que eu recentemente ouvi a invasão da terra Yanomami pelos garimpeiro. Mais de 70.000 garimpeiros, helicóptero, avião entrando, explorando, abusando das crianças, assassinando crianças, homens e mulheres no nosso território.

Eliezer: Bira le dijo que nunca había visto una invasión como la que había sufrido la tierra de los Yanomami por parte de los garimpeiros, los mineros ilegales, durante el gobierno de Bolsonaro. Los Yanomami son un pueblo indígena numeroso que vive en el norte de la región amazónica, en la frontera entre Brasil y Venezuela. Bira dijo que la invasión que sufrieron había sido fomentada por el gobierno. Dijo que esa misma violencia que los pueblos de la selva enfrentaban era la que había matado a Dom y a Bruno, pero que su trabajo no iba a morir con ellos. Que ellos fortalecieron más a la gente.

Bira: Eu lamento muito a história do Bruno e do Dom, mas eles fortaleceram mais a gente. O Bruno vai continuar vivo na alma de muitas lideranças espirituais. A missão do Dom no mundo, em especial na Amazônia, ela se fortaleceu. Eles se tornaram inspiração.

Eliezer: Por eso él estaba creando una nueva generación de liderazgos indígenas que se inspiren en esa lucha, dijo Bira, y buscando alianzas alrededor del mundo, para que no vuelva a ser una batalla aislada, solitaria.

Bira: Eu estou preparando uma nova geração de novas lideranças indígenas que se inspiram nessa luta e buscando a aliança em volta do mundo para que nós não seja mais isolado, sozinho. Para que outros jornalistas, outros indigenistas do Brasil e do mundo não seja tragicamente assassinado, como aconteceu com Bruno e com Dom Phillips.

Eliezer: Para que otros periodistas e indigenistas no sean trágicamente asesinados, dice Bira. Al contrario: para que sean respetados y reconocidos por los gobiernos del mundo.

Bira: Pelo contrário, que todos os indigenistas, todos líderes ambiental, ativistas ambientais sejam respeitado, reconhecidos pelos governos de todo o mundo, porque essas pessoas estão lutando pelo bem comum da humanidade. Não é só da floresta, não é só dos índios.

Eliezer: De nuevo, acostumbrado tal vez a que las cosas más obvias resulten opacas lejos de la selva, Bira vuelve a esta idea, que aparece detrás de su estrategia política, de sus proyectos, de sus alianzas: el mundo tiene que entender que las personas que están luchando por el ambiente no lo hacen para el bosque o para los indígenas. Lo que están defendiendo, dice, es un bien común.

Bira: Eu sou feliz de ser filho da Amazônia. Aqui é tudo para nós. Amamos esse lugar. Aqui está meu Deus, o meu Criador está aqui. nesse vento que sopra, nessa floresta que está em pé, nesse rio limpo que corre. Nós temos que proteger que a futuras gerações da humanidade possa também ter o privilégio de ver isso aqui.

Felipe: Qual é a importância, Bira, de receber visitas de pessoas que não são… de outras culturas aqui da vizinha?

Eliezer: Felipe le preguntó cuál era la importancia, para ellos, de recibir gente de otras culturas, de compartir la experiencia que ellos tenían de la Amazonía. Al final, por eso estábamos ahí, y por eso también quería venir Dom Phillips. Bira dijo que eso los había enriquecido. Que después de la opresión de los misioneros, que trataron de convencerlos de que su cultura era diabólica, ellos tenían vergüenza.

Bira: A gente tinha medo de botar a nossa cara para fora para não ser devorado. Mas agora nós saímos, botamos nossa cara pra fora. Tamo caminhando, tamo cantando, tamo feliz.

Eliezer: Primero tenían miedo de mostrarse al mundo, dijo Bira, para evitar que los comieran. Pero ahora habían salido, habían dado la cara. Dijo que ver a gente de afuera compartir con ellos la ayahuasca, los cantos, las ceremonias, la pintura, había fortalecido su autoestima y su confianza.

Bira: É a nova geração Yawanawá. Agora esqueceram disso. A minha família não, não vive o que eu vivo. A geração do meu povo não tem esse sentimento que eu tenho. Os meus filhos estão vivendo com a liberdade plena.

Eliezer: Ahora han convertido su identidad en motivo de orgullo. Las nuevas generaciones ya no sienten esa vergüenza por su cultura, por ser quienes eran. Pero ahora tenía otro problema, nos dijo Bira: los jóvenes yawanawá ya no quieren ir a estudiar afuera.

Bira: Em termos de proporção, a população indígena do nosso Estado, o maior grupo acadêmico, científico e yawanawá.

Eliezer: Bira contó que, en proporción, los yawanawá tienen la mayor cantidad de gente formada en la academia entre los pueblos indígenas del Estado. Médicos, cirujanos dentales, ingenieros forestales, biólogos, matemáticos…

Bira: Nós temos várias categoria, mas ninguém quer exercer essa função mais porque a nossa cultura é tão importante de ser um acadêmico.

Eliezer: Bira dice que los jóvenes ya no quieren seguir ejerciendo, porque la cultura se ha vuelto tan importante para ellos como la academia. Lo dice con orgullo también, porque es un problema bueno. Y porque sabe que él ha trabajado la mayor parte de su vida para eso.

Cuando se fue de su comunidad, a los 15 años, el cacique Bira soñaba con ser abogado para defender los derechos de su pueblo, pero encontró otro camino para hacerlo. Se volvió un líder político y espiritual, una referencia para ellos.

Bira: Estou tão feliz. Imagine se eu tivesse me formado em advogado. Onde é que eu estaria?

Eliezer: Quién sabe dónde estaría si se hubiese formado como abogado, dice Bira ahora, antes de que nos levantemos para volver a la aldea.

Bira: Será que eu ia contribuir tanto como estou contribuindo hoje com minha família? De trazer autoestima, confiança, fazer nossa cultura de um tesouro sagrado que não podemos abandonar, nunca, trocar por nada nesse mundo.

Eliezer: Tal vez no hubiera podido contribuir tanto, dice, y no hubiera podido traer autoestima ni confianza, ni hacer que su cultura se volviera algo sagrado, más valioso que cualquier otra cosa en el mundo.

Después de la primera entrevista, nos quedamos en la aldea y seguimos hablando con Bira los días siguientes. Fuimos varias veces a su casa, que siempre estaba llena de gente, de niños, de familia; comimos cocodrilo y paca, una especie de roedor gigante, que el cacique mismo había cazado la noche anterior, en una de las salidas que hacían para pescar y conseguir carne.

Bira: Tudo bem, queridas, você já almoçaram? já comeste?

Niñas: Sim, sim, sim

Bira: A gente deixaram um pouquito de yacare, um pouquito de paca

En esas conversaciones, Bira recordó sus comienzos y el del movimiento indígena en Acre en los 80, nos contó cómo los misioneros lo habían acusado de ser traficante y comunista, habló del cambio climático y el último verano en Europa.

Bira: Agora fui, tive na Inglaterra, um verão tão forte na Europa que nunca aconteceu isso… Realmente está a acontecer uma mudança climática muito grande em todo o mundo..

Eliezer: Una tarde, después de comer, mientras uno de sus hijos ensayaba canciones en la habitación de al lado, nos contó que hacía poco había sido invitado a Denver, en Estados Unidos, al mayor encuentro de expertos internacionales en el uso de sustancias psicodélicas. Y dijo que le llamó la atención cuando encontró una tienda que vendía cápsulas de ayahuasca…

Bira: Eu encontrei numa tenda que estavam comercializando cápsula de ayahuasca. Microdose de ayahuasca…

Eliezer: En su ponencia, nos contó Bira, él dijo que admiraba y respetaba los avances de la ciencia occidental, que los blancos habían hecho cosas buenas pero que no entendían lo que estaban haciendo mal. Que Estados Unidos invertía millones en buscar remedios para el malestar de su gente, pero que no era tan sencillo como tomar una cápsula. Que habían invadido países y destruido naciones, y ahora querían estar de fiesta, y eso no era posible.

Bira: Agora os países que vocês invadiram, que vocês destruíram nações, mataram muita gente. Vocês querem estar em festa nos Estados Unidos? Vocês tem que pagar e vocês estão pagando por isso. E o problema não é psicológico. O problema é espiritual. E vocês esqueceram da espiritualidade.

Eliezer: El problema es espiritual, les dijo Bira. Ustedes lo saben, pero se ignoran a ustedes mismos. Saben que la cura es espiritual, pero siguen haciendo un remedio. Porque no son capaces de poner dentro de la ciencia a los pueblos originarios…

Bira: Vocês sabem. Vocês ignoram vocês mesmo. Vocês gastam dinheiro com vocês. O próprio desafio de vocês. Vocês tem a consciência que essa cura espiritual e você continua fazendo um remédio. Porque vocês não são capazes de convidar gente. Porque vocês não são capazes de colocar dentro da ciência os povos originários…

Audio cantos

Eliezer: Todas las noches que estuvimos en la Aldea Sagrada, un grupo de música de una comunidad vecina ensayaba para una ceremonia colectiva de curación de la que iba a participar todo el pueblo. Al otro día de la ceremonia nos teníamos que volver. Antes de partir, le pregunté a Felipe cuál era la sensación que tenía.

Felipe: Lo que yo siento acá es los yawanawa es una sensación de miedo y esperanza. A donde estamos ahora, en la aldea sagrada de los Yawanawa, es un momento de mucha esperanza, de reconexión con la tierra, de aprender y admirar los cantos sagrados, el conocimiento, la belleza de la vida yawanawa, de la armonía que viven con la naturaleza. La naturaleza como parte fundante de la vida, porque nosotros somos la naturaleza. Pero seguro mañana, cuando empezamos a bajar a Cruzeiro y vamos a mirar lo que están haciendo los vecinos, los nuevos vecinos rancheros de los yawanawa, empezando la tala de los árboles, y vamos a empezar a mirar la deforestación. Ahí hay el miedo.

Eliezer: La única forma que había para resolver esa dialéctica entre miedo y esperanza, me dijo Felipe, era un concepto que había aprendido de sus 15 años de amistad con Bira: la lucha permanente.

Eliezer: Este episodio fue reportado y producido por Felipe Milanez y por mí. Lo editó Silvia. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. La mezcla y el diseño de sonido son de Elías González, con música compuesta por él y por Rémy Lozano.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Nausícaa Palomeque, Analía Llorente, Samantha Proaño, Paola Alean, Juan David Naranjo Navarro, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, Natalia Ramírez y Desirée Yépez. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Estudios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Estudios. Como te hemos contado durante este episodio, si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso sobre América Latina hoy más que nunca te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. Estamos en una situación crítica financieramente y tu apoyo nos permitirá seguir explicando a profundidad lo que ocurre en la región. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos a que El hilo siga vivo cada semana. Muchas gracias.

También puedes seguirnos en redes sociales, recomendar nuestros episodios y suscribirte al boletín de correo.

Yo soy Eliezer Budasoff, gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Eliezer Budasoff: Hi, we’re away this week, so we want to share an episode we reported a while back, but it touches on a topic that will be central this year: our relationship with the world’s largest tropical rainforest, the Amazon, where COP30, the United Nations Climate Change Conference, will be held in a few months. We’ll be back next week with a new episode.

Silvia Viñas: This episode was produced with support from the Amazon Rainforest Journalism Fund in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

Yawanawá chanting audio

Eliezer: It’s a Friday in late July, around 2 PM. In the Sacred Village of the Yawanawá, an indigenous people of the Brazilian Amazon, about 20 women have gathered to rehearse songs for a ceremony that will take place in a few days. They’re sitting in a circle under an enormous open-sided shelter, where their voices bounce off the roof, multiplying and projecting…

Yawanawá chanting audio

Eliezer: I’m in this village because of a double homicide, because of the story that British journalist Dom Phillips never got to tell—he was murdered in the Amazon in 2022 along with indigenous expert Bruno Pereira. But to understand why we traveled here, why Dom Phillips wanted to write about this community and its chief, it’s important to know this: the Yawanawá adore music. It’s an essential part of their collective life. Like other peoples in this region, the indigenous territory of the Gregory River in the Brazilian state of Acre, their music is melodic. The main focus is on the chants, which have a spiritual function. But in this case, they’re also a symbol of a political struggle.

Yawanawá chanting audio

Silvia Viñas: For about a decade, the Yawanawá were forbidden to sing. The people had been subjugated by evangelical missionaries who prevented them from practicing their rituals, holding celebrations, or speaking their language, and allowed rubber tappers to exploit them as semi-slave labor. Their traditions and knowledge were disappearing.

But 40 years ago, an 18-year-old who had left the community returned to expel the missionaries.

Chief Bira (audio in Portuguese): They convinced many of our indigenous peoples in the Amazon and the Americas, it was a very cruel system, the most ridiculous system in the name of peace, in the name of God, in the name of divine justice…

Eliezer: The man you’re hearing is that young man, the one who organized the expulsion of the evangelicals from his community. His name is Biraci Brasil Nixiwaka, and people call him Bira. Chief Bira is a historic figure in the Brazilian indigenous movement. He says the missionaries convinced many peoples in the Amazon and throughout the Americas, but it was a cruel system, the most ridiculous… in the name of peace, God, and divine justice.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): How can someone who speaks of peace and love, of healing, of salvation, criticize a culture, exploit traditional people, oppress our traditions.

Silvia: How can someone who speaks of peace and love, of healing, of salvation, says Bira, criticize a culture, exploit traditional people and oppress their traditions.

Since he was a teenager, Bira has led the fight for his people’s rights, for recognition of their territories and their autonomy. He was first a political leader, but he understood that he also needed to be a spiritual leader. They had to rebuild their culture and traditions, recover the knowledge and pride of who they were. Thus began a long process that took decades of work, but has turned the Yawanawá into a global example of cultural resistance and political strategy. That’s why journalist Dom Phillips wanted to interview him. And he asked his Brazilian colleague Felipe Milanez to make the connection. This is Felipe:

Felipe Milanez: Dom was working on a book about how to save the Amazon during one of the most violent periods in Brazil’s history, which was the Bolsonaro government. So much tragedy, so much destruction, increased deforestation rates, illegal mining, murders, death threats, and coming to Acre for Dom was also a moment of hope.

Yawanawá chanting audio

Silvia: Felipe is a professor and journalist who has spent years researching the culture and struggles of Brazil’s indigenous peoples. That’s how he met Chief Bira and learned the story of the Yawanawá. Felipe is an old friend of Bira’s and was also friends with Dom Phillips, and he connected the two because for his book, Phillips wanted to show that there were other ways of inhabiting this Amazon that was being devastated. But he never got to interview the chief.

Felipe: His last trip was supposed to be here, where we are, in the Sacred Village of the Yawanawá. And Bira was waiting for him when he learned of the tragedy.

Eliezer: That’s why we’re here, a year after the deaths of Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira, with Chief Bira, listening to a group of women rehearsing songs for a ceremony, while some villagers draw near as if hypnotized. The rituals and music for which the Yawanawá are now known are part of the story that Dom Phillips wanted to tell, and that we’re going to try to tell with Felipe in this episode. Because the community’s resistance strategy also has to do with this: with having managed to recover, along with their culture, the everyday possibility of beauty.

Yawanawá chanting audio

Eliezer: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: And I’m Silvia Viñas.

Today, a way to save the Amazon: the struggle of the Yawanawá people and the vision of Chief Biraci Nixiwaka, the interview that Dom Phillips never got to do.

Silvia: Journalist Dom Phillips and indigenous expert Bruno Araujo Pereira were murdered in June 2022, during the final months of Jair Bolsonaro’s government. It happened in the Javari Valley, one of Brazil’s largest indigenous territories, near the border with Peru.

Reporter: Brazil’s federal police confirm that the remains found in the Brazilian Amazon belonged to British journalist Dom Phillips.

Reporter: They were violently murdered due to criminal connections that the Brazilian state, under Bolsonaro’s government, failed to combat.

Reporter: A poacher arrested by police confessed to the crime and indicated where the bodies were.

Activist: Justice would be the continuation of Bruno’s work…

Reporter: Justice would be the continuation of Bruno’s work, of Bruno’s life, of Dom Phillips’ life who were in the forest alongside our territories to defend and protect our lives.

Eliezer: As we mentioned before, Phillips was working on a book about the future of the Amazon, threatened by violence and competing interests that weren’t new, but had been encouraged and unleashed by Bolsonaro’s government.

Felipe: Bolsonaro’s inspiration for his government was the military dictatorship, which was the government that began the invasion and destruction of the Amazon in 1970. Bolsonaro promoted the total and illegal exploitation of the Amazon’s economic frontiers: he supported the crime of deforestation, the crime of mining…

Silvia: Felipe had met Dom Phillips precisely because of their shared concern about what was happening to the world’s largest rainforest and its inhabitants.

Felipe: I got to know Dom through his work in the Amazon. I started reading Dom’s work and we connected through social media, exchanging information and then we started talking. Initially, I was a source for Dom.

Eliezer: Phillips had arrived in Brazil in 2007 as a cultural journalist focused on music, but over time the Amazon became his main interest. He published about it in outlets like The Guardian and The New York Times. A few years before his murder, he had moved with his wife to Salvador de Bahia, in the north of the country, where Felipe lives. That proximity ended up cementing their friendship, which grew stronger during the pandemic.

Felipe: We would go to the beach and do sports on these beautiful beaches of Salvador in magnificent Bahia, and while rowing through the bay, we would talk about the Amazon, exchange ideas. Dom would ask me questions about my experience in the Amazon, and I learned a lot from Dom about listening more to people, and also about talking less, you know?

Silvia: Felipe says that he also learned to see his country through Phillips’ eyes, someone who came from a working-class background in the outskirts of Liverpool, who knew his country’s colonial history and the horrors of monarchy, and thought about a more equal world. Both were interested in the resistance experiences of indigenous peoples. Felipe had known that world for almost 15 years, since he started working as a journalist for FUNAI, (Brazil’s National Indian Foundation).

Felipe: I learned as a Brazilian public servant doing work in defense of indigenous peoples. And there, when I worked at FUNAI, I met the great indigenous leaders in Brazil. I discovered a much more diverse country, much more enchanting than the country that existed for me before working at FUNAI.

Eliezer: At FUNAI, Felipe learned from Brazil’s most veteran indigenous experts, the sertanistas, who protected indigenous peoples’ rights. One of them, who had worked with isolated tribes and communities in the state of Acre, introduced him to Chief Bira, who at that time was fighting to expand the boundaries of the Yawanawá’s territory.

Felipe: It was a very quick friendship because of my admiration, because of Bira’s friendliness—he’s someone who is very open and always knows how to recognize potential allies—and on my part, an admiration, an enchantment that I have with this generation that led the revolution in Brazil’s indigenous movements in the ’80s.

Silvia: In the 1980s, Bira had achieved the first recognition of indigenous lands in the state of Acre, while the country was still under dictatorship. That was the starting point for them to expel the rubber tappers and missionaries from their territories.

Eliezer: Felipe told me something that the indigenous expert who first introduced him to Chief Bira always used to say, the one who told him about the struggles of the Yawanawá and other peoples in the state of Acre:

Felipe: The worst types out there are the miners, the loggers, and the missionaries, but of all of them, the missionaries are the worst, because until the end they’ll try to invade indigenous territories and destroy the indigenous territory from within.

Eliezer: Felipe explained to me that the missionaries had arrived under the pretext of doing humanitarian work, supposedly to look after the health and education of the communities, but in reality they were only interested in translating the Bible and converting the indigenous people to exploit them. They manipulated them in exchange for medicines, and there were missionaries who were allied with a company called Paranacre, which enslaved the Yawanawá. The company had bought an area of rubber plantations to extract timber and exploit the land for cattle ranching… And Bira led the fight to expel them from the territory and recover their lands.

Silvia: Bira was a fellow fighter alongside Chico Mendes, the environmental activist murdered by ranchers who became a global symbol, and Marina Silva, Brazil’s current Minister of Environment—both were also from the state of Acre. The chief was part of the group that in the eighties created the Alliance of Forest Peoples, which brought together indigenous and riverside communities of the Amazon with rubber tappers. He even ran for congress. But when Felipe met him, Bira was in the middle of a process of rebuilding his culture and traditions.

Felipe: The Yawanawá were already… They were already known for their great creativity, for doing new things, receiving well-known people from around the world, actors, environmentalists.

Eliezer: Actor Joaquin Phoenix, for example, visited them in the early 2000s to film a documentary. This month, Leonardo DiCaprio met with Bira at an event. The actor is supporting a digital art project that the Yawanawá are participating in, as they have built networks all over the world. Among other things, years ago they made an agreement with the U.S. cosmetics company Aveda, which they supply with achiote or urucum, a pigment they use to paint their bodies.

Felipe: A very creative people, with many ideas, with great autonomy. And they were managing the defense of their territory, the defense of their culture with arts, music, festivals, and with great spiritual strength.

Silvia: In 2000, they created the annual Mariri Yawanawá festival, which aims to preserve the people’s culture and traditions. It brings together 17 villages and lasts about a week. There are chants, dances, ceremonies, games… And it’s one of the few indigenous festivals that’s open to a limited number of tourists.

Eliezer: Felipe first visited the Yawanawá in 2007, invited by Bira and captivated by his leadership strategy, which had understood that his people’s spiritual dimension was a powerful political tool.

Felipe: It was a moment to hear the stories for the first time, in their own words, about the violence of the military dictatorship in Brazil and in Acre. And it was also when I heard from Bira his testimony about the cultural violence of the missionaries, about ethnocide, about racism, and about how a leader became aware of this form of oppression, tried to mobilize his people, and from that insurgency sought freedom and autonomy.

Silvia: In the following years, Felipe returned to Bira’s lands, learned about their history and from the people’s most ancient shamans. And he worked with the chief to capture part of his experience in writing.

It’s not surprising, then, that Felipe talked about Chief Bira and the Yawanawá with his friend Dom Phillips, who was documenting stories of resistance and hope in the Amazon in the face of Bolsonaro’s policies… a government inspired by the dictatorship, which encouraged indiscriminate exploitation of the rainforest and shared the evangelical missionaries’ racist view of indigenous culture.

Eliezer: By then, when they talked about their experiences and did sports together on the beaches of Bahia, Felipe was already dedicated almost entirely to academic work and teaching. In late 2021, while doing a postdoctoral stay in New York, he received a message from Phillips asking if he could give him Bira’s phone number.

Felipe: At this point, I was no longer just a source for Dom, but a colleague in exchanging ideas. And I made contact with Bira. I spoke with Bira and passed Bira’s contacts to Dom. And Dom started calling, seeing, exchanging messages with him too to organize his mission in Acre, to visit the Asháninka and the Yawanawá as two peoples who today are examples of defending their territory and culture. They are global examples of how a community can develop well, live well, and protect nature for future generations.

Silvia: In early 2022, while exchanging messages, Phillips told Felipe that he already had dates for his trip.

Felipe: Dom had organized a trip between May and June last year between the Javari Valley and Acre.

Eliezer: First, he went to visit the Asháninka, a majority indigenous people in Peru, with a small population in the state of Acre, where the Yawanawá lands are also located.

Felipe: After the Asháninka, he was going to come visit Bira, but Bira had to do a spiritual retreat and postponed Dom’s trip for another month.

Silvia: So Dom went to the Javari Valley to interview the indigenous people who worked with indigenous expert Bruno Pereira. The plan was that after that he would return to the state of Acre to interview Bira. But he never arrived. On June 5, 2022, while they were traveling through the Javari Valley to document Bruno’s work with riverside and indigenous residents to protect the territory from invasion by mafias and drug trafficking, both disappeared. Two days later, Felipe sent his last message to Dom Phillips’ phone.

Felipe: Unfortunately, the last message I sent him, something like a hope that I tried to keep in my heart. June 7, 2022: “Hoping everything is okay with you, Dom. Very much.”

Eliezer: He said: hoping everything is okay with you. The message was never received.

While they were still missing, President Jair Bolsonaro said that the British journalist was disliked in the region because he did many reports against illegal miners and environmental issues.

[Archive] Jair Bolsonaro, former president of Brazil (audio in Portuguese): This Englishman, he was disliked in the region because he did many stories against miners and environmental issues…

Silvia: He also said they had gone alone into an inhospitable area, without security. In reality, Bruno Pereira knew the area very well. He had been coordinator of indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation at FUNAI, where he worked to expel illegal miners, and Bolsonaro’s Government removed him from his position. In his place, ironically, they appointed a pastor who had worked as an evangelical missionary in the Amazon.

Eliezer: Ten days after the men disappeared, a fisherman detained by police confessed to participating in the murder and led investigators to where they had buried the remains.

Silvia: After the break, the interview that Dom Phillips never got to do. We’ll be right back.

[Ambient sound: Brasilia airport]

Eliezer: I’m at the Brasilia airport, where we planned to meet with Felipe to catch the only daily flight to Cruzeiro do Sul, in the state of Acre. There’s no easy way to reach Yawanawá lands, whether you’re coming from another country or another state in Brazil. From the country’s capital, it’s a five-hour flight to Cruzeiro. We landed at midnight, got some rest, and hopped into a car.

Felipe: It’s five-thirty in the morning now, and we’re waking up. It’s still dark outside. We’re driving down the road to a port called São Vicente, where the road crosses the Gregorio River.

Eliezer: After nearly three hours on the road, we arrived at a small port along the Gregorio River. We boarded a boat and traveled for another seven hours before finally arriving.

Felipe: Woohoo! We made it, my friend. We’ve just arrived at the Sacred Village of the Yawanawá. It’s three-thirty in the afternoon. So beautiful, so beautiful…

Eliezer: The Yawanawá aren’t a large tribe. They have a population of around 1,200 people, most of whom live in communities along the banks of the Gregorio River. The Sacred Village, where we are now, is small but serves as the place where they usually host visitors.

“A true global village,” says Chief Bira, who lives here with part of his family. He welcomed us warmly and gave Felipe a hug.

[Conversation in Portuguese]

Felipe: How exciting.

Bira: How are you, dear? Welcome.

Felipe: I missed you all so much…

Bira: It’s been so long.

Felipe: Back here in the Sacred Village…

Eliezer: When we arrived, the community was preparing to host about 30 women from around the world, who were coming for a spiritual retreat led by Putany, Bira’s wife and the first female shaman of the community. They were also expecting a small group of technicians from an NGO helping the community map resources and activities within their territories. Bira showed us where we’d be sleeping—a cabin with a thatched roof and wooden posts for hanging hammocks. He gave us a tour of the village and told us to find him the next day for our interview.

[Birdsong and ambient sounds of the Sacred Village]

Eliezer: The next morning, before looking for the chief, I asked Felipe to describe where we were and what we could see.

Felipe: We’re lying in hammocks, talking, while we can hear Bira, who’s been meeting with the community since 4:00 a.m. Chief Nixiwaká has been organizing tasks, assigning jobs, and telling stories. From here, we’re on a high point in the village overlooking the Gregorio River. You can see the forest, so beautiful, with trees 30 or 40 meters tall right in front of us. That’s part of Yawanawá life—the everyday presence of beauty, the aesthetics of everything here. The aesthetics of the village, their clothes, their body paint, their way of life. And their deep admiration for the forest, for the Amazon rainforest.

Eliezer: Later in the morning, we went to Bira’s house. He came out with one of his sons and a nephew, and we started walking toward the forest. As we moved away from the center of the village, we saw solar panels, isolated houses, spiritual retreat spaces, a sacred cemetery, medicinal herb gardens, and an ayahuasca plantation.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): The Sacred Village of the Yawanawá has the largest plantation of queen vine leaves used to make ayahuasca. The largest in the Amazon is here…

Eliezer: Bira explained that they have the largest plantation of plants used to make ayahuasca, one of the main traditional medicines of Indigenous peoples. The Yawanawá are renowned for their ancestral knowledge of ayahuasca, and Bira has participated in global conferences on the use of psychedelics. We’ll discuss this more later, but at that moment, we continued walking until we reached a clearing in the forest. We sat on some logs, and Felipe began to speak.

First, he told Bira about his conversations with Dom Phillips and the book Phillips was working on—what he was trying to understand.

Felipe (audio in Portuguese): He wanted to learn about the Yawanawá experience during such a violent time in Brazil. He saw it as a place of hope where things were going right…

Eliezer: Felipe explained that one of the reasons we were there was to hear Bira’s thoughts on how to answer Phillips’ question about saving the Amazon. Bira began a long reflection, sharing his thoughts, the events that had shaped his worldview, and what had made the Yawanawá who they are today.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): I’ve seen how white society weakens us—when they divide us and when they undermine the social, cultural, and spiritual organization of our peoples.

Eliezer: Bira said he had observed how white society weakened Indigenous peoples by dividing them and undermining their organization. That’s why he has always focused on strengthening their internal unity, ensuring they face challenges collectively. He said the system created by white people to invade and exploit Indigenous lands—under the pretext that Indigenous peoples hinder development—was a failed system.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): The economy hasn’t brought social good to humanity. On the contrary, it has created more violence, wars, global warming, and increased poverty worldwide. More and more people are going hungry around the world. So how can you say we’re the ones holding things back when your society keeps deteriorating more and more?

Eliezer: For Bira—and this is something he conveys in many ways—it’s clear that the one in need of help is Western society. Bira explained that their work in preserving the rainforest is fundamental for humanity, but it can’t be a solitary effort. He stressed the importance of forming global alliances and creating a parallel system to the current one, which views the Amazon only as a resource to exploit.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): We need to build something parallel to this system, but without excluding it, right? It’s possible to use technology today, participate in the economy, and still preserve the forest, maintain our culture, keep our families together, and live peacefully in the village.

Eliezer: Preserving the rainforest, Bira says, doesn’t mean rejecting technological advancements. It means recognizing the transcendence of Indigenous culture and knowledge, as they are the only ones who understand the language of nature.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): We Indigenous peoples, the original peoples, are the only ones on the planet who can speak the language of nature—the language of the birds, the trees, the animals, the fish. We understand the movements of the stars, the wind, the sun, the moon, and the constellations.

Eliezer: Bira explained that they know medicinal and sacred plants, their names, and how to communicate with their spiritual world.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): We can translate this for humanity. But how can we do that? We are excluded from the system

Eliezer: It’s impossible, Bira says, to translate their knowledge of nature if they are excluded from the system.

Felipe asked Bira about Bolsonaro and the connection between what happened to the Amazon during his government and the Yawanawá’s fight to free themselves from missionaries and exploitation.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): In all my life, I have never seen an invasion like the one the Yanomami lands suffered from the garimpeiros. More than 70,000 illegal miners, helicopters, planes entering, exploiting, abusing children, and killing men, women, and children in our territories.

Eliezer: Bira said he had never witnessed an invasion like the one endured by the Yanomami during Bolsonaro’s presidency. The Yanomami, a large Indigenous group living in the northern Amazon on the border between Brazil and Venezuela, faced a brutal invasion fostered by the government. Bira explained that the same violence faced by forest peoples also claimed the lives of Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira. But their work, he said, wouldn’t die with them. Instead, it strengthened their community.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): I deeply regret the story of Bruno and Dom, but they made us stronger. Bruno will live on in the soul of many spiritual leaders. Dom’s mission in the world, especially in the Amazon, has been strengthened. They’ve become an inspiration.

Eliezer: That’s why Bira was working to create a new generation of Indigenous leaders inspired by their struggle, and he was seeking alliances worldwide to ensure it wouldn’t be a solitary, isolated battle.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): I am preparing a new generation of Indigenous leaders inspired by this struggle, and I am seeking alliances around the world so that we are no longer isolated and alone. So that other journalists and Indigenous advocates, in Brazil and the world, are not tragically murdered like Bruno and Dom Phillips.

Eliezer: So that other journalists and Indigenous advocates aren’t tragically killed, Bira says, but instead are respected and recognized by governments worldwide.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): Because these people are fighting for the common good of humanity. Not just for the forest, not just for Indigenous peoples.

Eliezer: Perhaps accustomed to the fact that what is most obvious to him might seem opaque outside the forest, Bira returned to this central idea, which informs his political strategy, his projects, and his alliances: the world must understand that those fighting for the environment aren’t doing it solely for the rainforest or Indigenous peoples. What they are defending, he says, is a shared common good.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): I’m happy to be a child of the Amazon. Everything is here for us. We love this place. My God, my Creator, is here—in this blowing wind, in this standing forest, in this clean river that flows. We must protect this so future generations of humanity can also have the privilege of witnessing it.

Felipe (audio in Portuguese): Bira, what’s the importance of hosting people from other cultures here?

Eliezer: Felipe asked him about the significance of welcoming people from other cultures and sharing their Amazonian experience. After all, that’s why we were there, and it’s also why Dom Phillips wanted to come. Bira said it had enriched them. After years of missionary oppression, which tried to convince them that their culture was evil, they had felt shame.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): We were afraid to show our faces, afraid of being devoured. But now we’ve come out. We’re showing our faces, we’re moving forward, we’re singing, we’re happy…

Eliezer: At first, they were afraid to show themselves to the world, Bira said, to avoid being consumed. But now they had emerged; they had shown their faces. He said that seeing people from outside sharing ayahuasca, songs, ceremonies, and painting with them had strengthened their self-esteem and confidence.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): This is the new Yawanawá generation. Now, they’ve forgotten about that fear. My family doesn’t live the way I live. My people’s generation doesn’t feel what I feel. My children are living with complete freedom.

Eliezer: Now they have turned their identity into a source of pride. The new generations no longer feel shame for their culture, for being who they are. But now they have another problem, Bira told us: Yawanawá youth no longer want to study outside. They have many people with university degrees, he explained: doctors, dentists, forest engineers, biologists, mathematicians…

Bira (audio in Portuguese): We have various professionals, but no one wants to work in those roles anymore because our culture is as important as being an academic.

Eliezer: Bira says that the youth no longer want to pursue those careers because their culture has become just as important to them as academia. He says this with pride, too, because it’s a good problem. And because he knows he has spent most of his life working toward that.

When he left his community at 15 years old, Chief Bira dreamed of becoming a lawyer to defend his people’s rights. But he found another way to do it. He became a political and spiritual leader, a reference for his people.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): I’m so happy. Imagine if I had become a lawyer. Where would I be?

Eliezer: Who knows where he’d be if he had become a lawyer, Bira says now, before we stand up to return to the village.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): Would I have contributed as much as I’m contributing today to my family? By bringing self-esteem, confidence, and making our culture into a sacred treasure we must never abandon, never trade for anything in this world?

Eliezer: Maybe he wouldn’t have been able to contribute as much, he says, and wouldn’t have been able to bring self-esteem or confidence, or turn their culture into something sacred, more valuable than anything else in the world.

After the first interview, we stayed in the village and kept talking with Bira over the following days. We went to his house several times, which was always full of people, children, family. We ate crocodile and paca, a type of giant rodent, which the chief himself had hunted the night before, during one of the outings they made to fish and get meat.

[Ambient sound, Bira’s house, voices in Portuguese]

Bira: How are you, my dears? Have you had lunch yet? Have you eaten?

Girls: Yes, yes, yes.

Bira: We left a little crocodile, a little paca…

Eliezer: In those conversations, Bira recalled his beginnings and the early days of the Indigenous movement in Acre in the 1980s. He told us how missionaries had accused him of being a trafficker and a communist, and he talked about climate change and the last summer in Europe.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): I went to England recently. It was such a hot summer in Europe, something that had never happened before. Climate change is truly happening all over the world.

Eliezer: One afternoon, after lunch, while one of his sons rehearsed songs in the next room, he told us that he had recently been invited to Denver, in the United States, to the largest gathering of international experts on the use of psychedelic substances. And he said he was surprised when he found a shop selling ayahuasca capsules…

Bira (audio in Portuguese): I found a tent where they were selling ayahuasca capsules. Microdoses of ayahuasca…

Eliezer: In his presentation, Bira told us, he said he admired and respected the advances of Western science, that white people had done good things but didn’t understand what they were doing wrong. That the United States invested millions in searching for remedies for the discomfort of its people, but it wasn’t as simple as taking a capsule. That they had invaded countries and destroyed nations, and now they wanted to celebrate, but that wasn’t possible.

Bira (audio in Portuguese): The countries you invaded, the nations you destroyed, the people you killed… Now you want to celebrate in the United States? You have to pay, and you are paying for it. And the problem isn’t psychological. The problem is spiritual. And you have forgotten spirituality…

Eliezer: The problem is spiritual, Bira told them. You know it, but you ignore yourselves. You know that the cure is spiritual, but you keep making medicine. Because you’re not capable of including Indigenous peoples in science…

Bira (audio in Portuguese): You know this. You ignore yourselves. You spend money on yourselves. It’s your challenge. You’re aware that this is a spiritual cure, yet you keep making medicine. Because you’re not capable of inviting us. Because you’re not capable of including Indigenous peoples in science…

[Yawanawá songs audio]

Eliezer: Every night we stayed in the Sacred Village, a music group from a neighboring community rehearsed for a collective healing ceremony that the whole village was going to participate in. The day after the ceremony, we had to leave. Before departing, I asked Felipe how he felt.

Felipe: What I feel here among the Yawanawá is a sense of fear and hope. Where we are now, in the Sacred Village of the Yawanawá, it’s a moment of great hope, of reconnection with the earth, of learning and admiring the sacred songs, the knowledge, the beauty of Yawanawá life, of the harmony in which they live with nature. Nature as the foundation of life, because we are nature. But surely tomorrow, when we start descending to Cruzeiro and see what the neighbors are doing—the new rancher neighbors of the Yawanawá, starting to cut down the trees—and we begin to see the deforestation, that’s where the far comes in.

Eliezer: The only way to resolve this dialectic between fear and hope, Felipe told me, was a concept he had learned in his 15 years of friendship with Bira: permanent struggle.

[Yawanawá songs audio]

Eliezer: This episode was reported and produced by Felipe Milanez and me. It was edited by Silvia Viñas. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. The sound design and mixing were by Elías González, with music composed by him and Rémy Lozano.

The rest of El hilo’s team includes Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Nausícaa Palomeque, Analía Llorente, Samantha Proaño, Paola Alean, Juan David Naranjo Navarro, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, Natalia Ramírez, and Desirée Yépez. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Estudios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios. As we’ve told you throughout this episode, if you value independent and rigorous journalism about Latin America, now more than ever, we ask you to join our membership program. We are in a critical financial situation, and your support will allow us to continue explaining in-depth what’s happening in the region. Visit elhilo.audio/donate and help keep El hilo alive every week. Thank you so much.

You can also follow us on social media, recommend our episodes, and subscribe to our newsletter.

I’m Eliezer Budasoff. Thank you for listening.