Chile

Dictadura

Pinochet

Democracia

Adopciones

Adopción

Nos Buscamos

Constanza del Río

Jimmy Lippert-Thyden González

Ilegales

Robo

Aniversario

Niños

Niñas

Bebé

Pobreza

Madre

Esta semana se cumplieron 35 años desde el retorno a la democracia en Chile, pero una de sus deudas más grandes sigue sin resolverse: el robo y la adopción ilegal de niños y niñas, una práctica que se extendió por décadas y que alcanzó su punto más oscuro durante la dictadura. Se estima que decenas de miles de niños fueron separados de sus familias con la complicidad o indiferencia del Estado. Uno de ellos es Jimmy Lippert-Thyden González, un abogado estadounidense que creció en Virginia sin conocer toda la verdad sobre su origen. En su búsqueda, se encontró con la ONG Nos Buscamos, que lo conectó con una historia mucho más compleja de lo que imaginaba. Esta semana, hablamos con Jimmy sobre su experiencia y con Constanza del Río, directora de Nos Buscamos, sobre una red de tráfico de niños que operó en Chile durante más de 40 años y sigue impune.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Daniela Cruzat -

Edición

Silvia Viñas, Eliezer Budasoff -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción en redes sociales

Samantha Proaño, Natalia Ramírez, Juan David Naranjo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

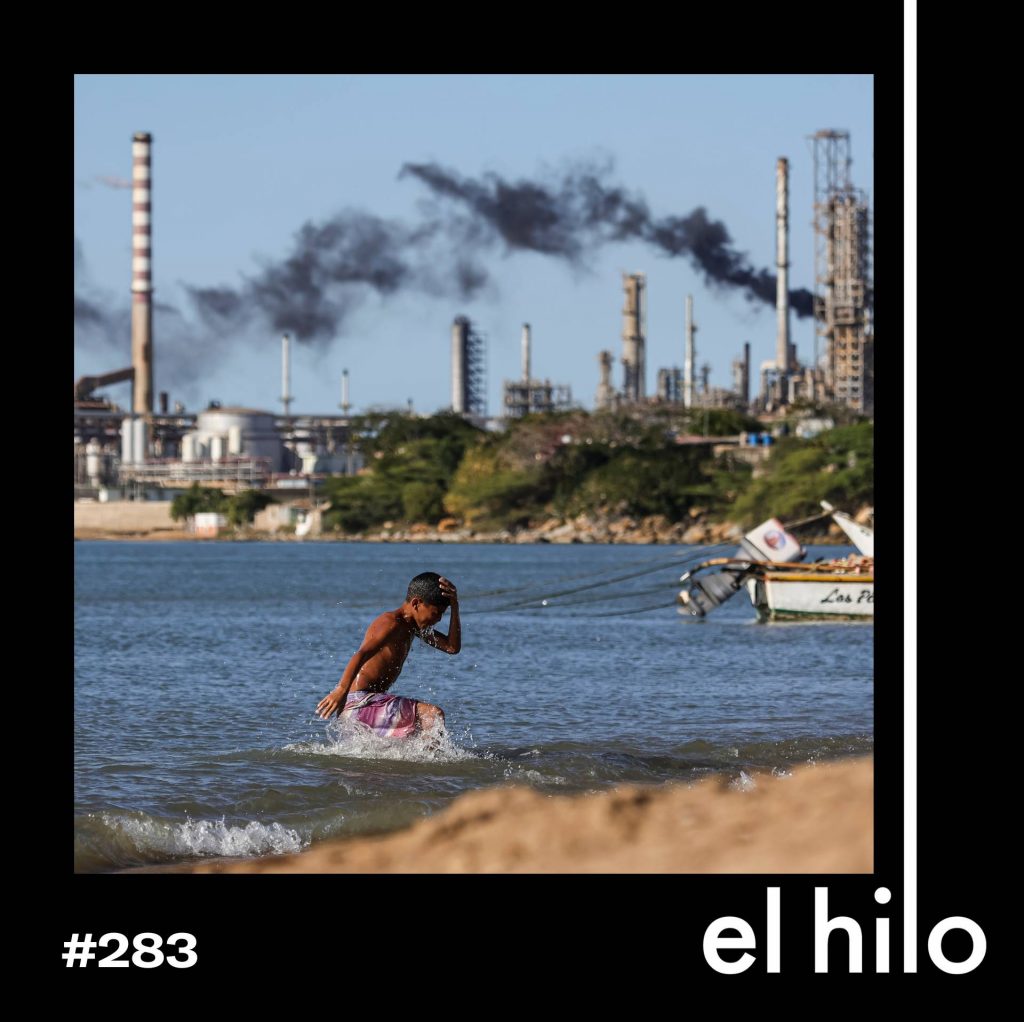

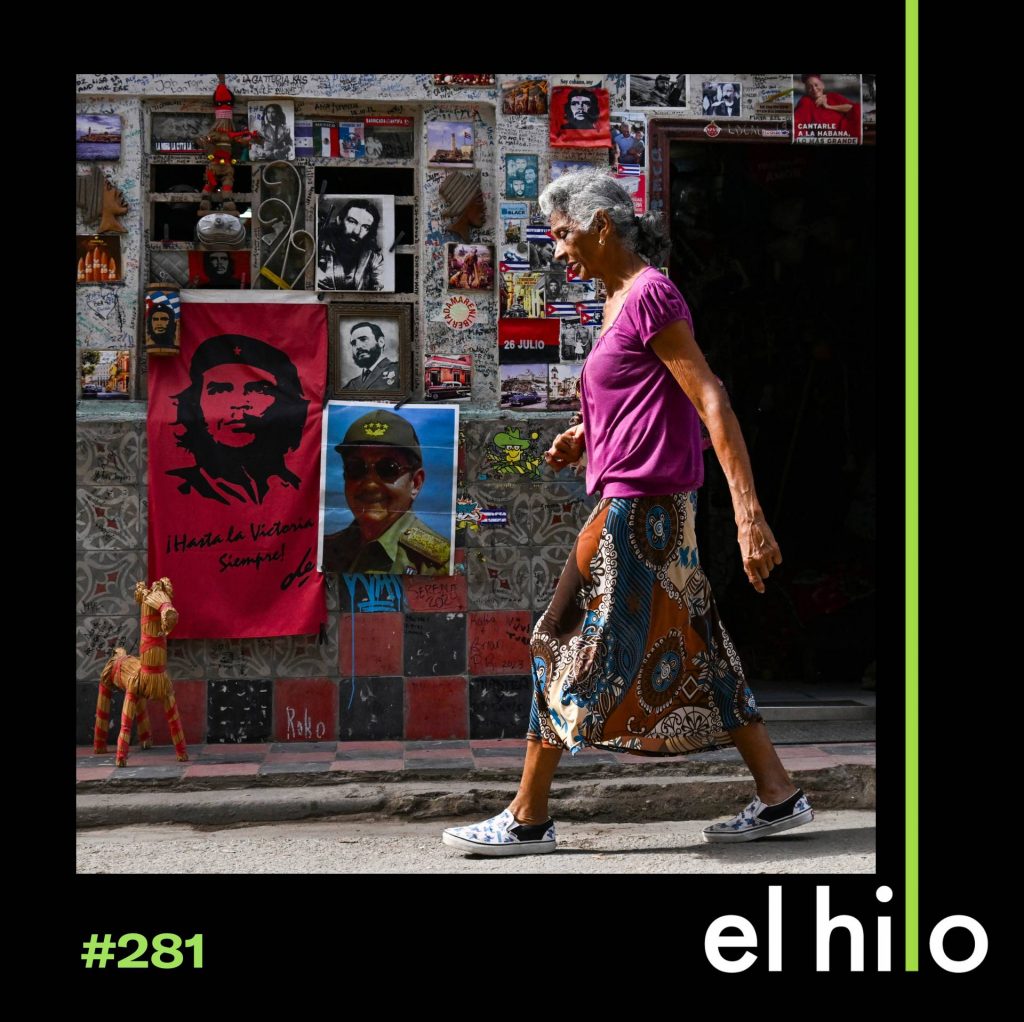

Fotografía

Gentileza de Nos Buscamos y Jimmy Lippert-Thyden González

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Silvia Viñas: Los papás de Jimmy nunca le ocultaron que era adoptado. Sabía que no habían podido tener hijos… que decidieron adoptar para darle a un bebé una buena vida.

Jimmy: Es un sueño para ellos. Pero para mí es un poquito diferente, porque yo sé, estoy en una familia con mucho amor y con muchas oportunidades, pero la verdad es… no soy gringo.

Eliezer Budasoff: Jimmy creció en el estado de Virginia, en Estados Unidos. Llevaba el apellido Lippert-Thyden, pero desde pequeño sabía que sus raíces no estaban en Estados Unidos. Había nacido en Chile. Y se sentía diferente. Primero, porque le parecía que nadie se veía como él.

Jimmy: Estoy en un barrio sin latinos. No hay ningún latino en mi comunidad, en mi escuela.

Silvia: Aprendió español porque tomó un curso durante un año…

Jimmy: Toda mi vida, cuando personas dicen, ¿de dónde eres? Nunca dije, soy de los Estados Unidos. Siempre soy de Chile.

Eliezer: Aunque nunca había estado ahí. Jimmy nos contó que sus padres adoptivos le decían que su mamá biológica lo había dado en adopción porque quería una mejor vida para él.

Jimmy: Y por esta razón, con todo amor tú eres adoptado a un otro país. Pero para mí no es tan simple.

Silvia: Sentía que algo no encajaba en esa historia.

Jimmy: Siempre sentí que… ¿dónde está la evidencia de eso?

Silvia: Jimmy se preguntaba: si su mamá biológica había querido lo mejor para él, ¿por qué no había dejado una carta o algo explicando su decisión?

Jimmy: Para evidencia del amor. Para evidencia de la historia. Pero yo no tengo nada.

Eliezer: Pasó mucho tiempo antes de que Jimmy confirmara su presentimiento. Cuando tenía 31 años, su mamá adoptiva le mostró los papeles de su adopción.

Silvia: Ahí, en una carpeta con distintos documentos, encontró varias versiones de por qué lo habían entregado. Pero eran contradictorias. Por ejemplo, una decía que no se sabía quién era su mamá, pero otra decía que no tenía familiares vivos. Y en una figuraba que su madre lo había dado en adopción cuando tenía dos años.

Jimmy: Y por esta razón pienso que hay algo más. No sé qué. Y para mí es tan difícil para visitar en otro país y es mucha plata para hacerlo.

Eliezer: Además en esa época, el 2011, Jimmy estaba en la marina y dice que no era fácil conseguir un permiso para viajar.

Silvia: Pero siguió con la duda. Más de una década después, en abril del 2023, cuando Jimmy tenía 42 años, su esposa se topó con una historia en la prensa…

Jimmy: Mi esposa dice que necesitas leer eso. Es increíble.

Jimmy: Y en esa noticia, un hombre, Scott Lieberman…

Audio de archivo, presentador: Scott Lieberman dice que siempre supo que era adoptado y que había nacido en Chile. Lo que no sabía era toda la verdad sobre cómo ocurrió la adopción. Hace unos meses se enteró de que en la década de los setentas y ochentas hubo muchos casos de bebés robados en Chile y vendidos a agencias de adopción.

Eliezer: Medios de todo el mundo compartieron la historia de Scott Lieberman, porque logró reencontrarse con parte de su familia en Chile y comprobar que había sido robado y dado en adopción ilegalmente.

Jimmy: Yo recuerdo cuando leo eso, solo pienso que, ay, qué horrible. Pero pienso, si eso es mi historia, es más simple.

Silvia: Más simple, dice Jimmy, porque explicaría por qué en sus papeles de adopción había tantas versiones diferentes.

Eliezer: Pensó que esas contradicciones buscaban esconder la verdad: que había sido robado durante la dictadura militar, al igual que otros más de 20 mil niños y niñas. No se equivocaba.

Eliezer: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: Y yo soy Silvia Viñas.

Esta semana se cumplieron 35 años del retorno a la democracia en Chile, y el Estado llega a este aniversario con varias deudas históricas. Entre ellas, la del robo y la entrega de bebés a familias en el extranjero: un sistema de complicidades que gestionó la adopción ilegal de decenas de miles de niños chilenos durante más de cuatro décadas, y fue legitimado y blindado por la dictadura.

Organizaciones de víctimas denuncian que, desde el retorno a la democracia, ningún gobierno se ha encargado de reconocer formalmente estos hechos, ni ha buscado una forma de justicia y reparación. Pero además, muchos casos demuestran que las redes de tráfico siguieron operando después del régimen de Pinochet.

Hoy, una historia de impunidad y derecho a la identidad que pone a Chile frente al espejo.

Es 14 de marzo de 2025.

Eliezer: Cuando Jimmy leyó la noticia de Scott Lieberman, el hombre que se había reencontrado con su familia chilena, vio información que tal vez lo podría ayudar a aclarar su historia.

Silvia: Lieberman había trabajado con una ONG chilena que se llama Nos Buscamos. Ayudan a familias separadas por el tráfico infantil a reencontrarse. Jimmy entró a su sitio web y llenó un formulario.

Jimmy: Con todo mi historia y con fotos de todos mis documentos. Y pienso que ojalá ellos van a llamarme quizás en seis meses, quizás ellos van a trabajar en mi caso no, yo no sé, pero es posible.

Constanza del Río: Nosotros, inmediatamente, como a los 20 minutos, le mandamos un mail diciendo que se baje el whatsapp para poder hablar.

Eliezer: Ella es Constanza del Río, la creadora y directora de la ONG Nos Buscamos.

Jimmy: Constanza es lo mismo de mí. Ella no puede esperar por nada. Me encanta eso de ella.

Constanza: Y a la media hora a la hora ya estábamos hablando y lo primero que él me dice es quiero descartar, quiero que me confirmes que yo no soy traficado, porque es muy espantoso darse cuenta que, que no es la historia que te habían contado toda la vida.

Constanza: Jimmy. Es el caso 5.482 de nuestra base de datos. Hoy día ya tenemos más de 7.000.

Silvia: La Policía de Investigaciones de Chile estima que entre los años 50 y los 90, más de 20 mil bebés y niños fueron separados de sus familias y dados en adopción ilegalmente. Buena parte fueron entregados a familias en el extranjero. Y sí, esa cifra incluye más de 20 años antes de la dictadura de Pinochet, que fue entre 1973 y 1990.

Eliezer: Pero durante la dictadura, estas adopciones ilegales se intensificaron.

Constanza: Era importante sacar la mayor cantidad de niños de Chile, uno para sacárselos de encima y dos para poder controlar mejor al pueblo. Era una forma de represión, una forma de manejar y una forma de evitar una carga también para el Estado.

Eliezer: De acuerdo con investigadores, la adopción de niños chilenos desde el extranjero le permitía al régimen ahorrar gasto público y controlar el crecimiento de la población. Pero además, Constanza dice que la dictadura ofrecía una justificación ideológica y hacía imposible que una madre joven, sin recursos, pudiera reclamar contra el Estado o las instituciones involucradas.

Silvia: Los niños eran traficados bajo una red de instituciones públicas y privadas que operaban bajo engaños. Eran médicos, matronas, asistentes sociales, sacerdotes, funcionarios públicos, jueces y abogados que orquestaban todo. Según la organización Nos Buscamos y otras investigaciones, cobraban hasta decenas de miles de dólares por niño.

Constanza: Eran siempre, siempre, siempre el mismo blanco: mujeres de escasos recursos. Menores de edad en muchos casos. Analfabetas, etcétera. Y que los traficantes de guaguas, las asistentes sociales de los hospitales públicos de Chile captaban a todas las mujeres que entraban, la que entraba con el marido, con la mamá, con la suegra, con una hermana. Esa no. La que era muy empoderada, la que era muy gritona y muy mandona, tampoco. La que era tímida, la que va asustada, la que está angustiada. Ese era el blanco. Y ahí se tiraban como cuervos.

Eliezer: En este contexto es que Jimmy fue adoptado. Y pronto iba a descubrirlo.

Silvia: El equipo de Constanza en Nos Buscamos se puso a investigar su caso el mismo día que Jimmy llenó el formulario con la información que tenía sobre su adopción.

Constanza: Lo que se hace normalmente con los adoptados es: se registran en nuestra base de datos, nosotros buscamos su antecedente a ver si es que tiene el número de RUT.

Silvia: RUT. Así le dicen en Chile al número de identidad. El DNI en otros países. Se lo dan a los bebés cuando los inscriben en el Registro Civil.

Eliezer: Y Jimmy tenía este número entre sus papeles. Eso fue muy útil para el equipo de Nos Buscamos, porque así, rápidamente, podían comprobar si había sido traficado.

Constanza: ¿Por qué? Porque a los adoptados legales, lo que debería suceder es que su nombre original y su RUT original se ha borrado del Registro Civil para dar así cabida a la nueva identidad en Italia o aquí mismo en Chile o en Estados Unidos, o donde sea.

Silvia: Cuando ingresaron el número de identidad de Jimmy en las bases de datos públicas, seguía ahí… Pero no tenía el mismo nombre.

Constanza: A los pocos minutos, porque somos un equipo grandote de investigadores, nos pusimos en contacto con Jimmy y le dijimos de rompe raja. Lamentablemente te tengo que confirmar que sí eres parte de los traficados.

Eliezer: ¡Wow! O sea, se lo dijeron el mismo día, unos minutos después de la llamada.

Constanza: El mismo día.

Eliezer: El siguiente paso era que alguien de Nos Buscamos fuera al Registro Civil a pedir los documentos originales del nacimiento de Jimmy.

Constanza: Y no aparecía ni madre ni padre. Nada, nada, nada, nada, nada. Todo así. Todo escondido. Cuando sucede eso es porque es tráfico.

Silvia: Pero en los papeles que les había pasado Jimmy había datos útiles, como su fecha de nacimiento, el 31 de octubre de 1980. También aparecía la dirección de un orfanato en Santiago, aunque no está claro dónde pasó sus primeros años de vida, porque habría sido adoptado cuando tenía dos años.

Constanza: De todos los documentos que habíamos logrado así interpretar. Teníamos una pista de que la madre se llamaba María González.

Constanza: Si es que Jimmy no se había hecho ADN, se lo tenía que hacer ya.

Jimmy: Y pienso que no quiero hacerlo porque soy un abogado de defensa criminal. Y yo sé todas las cosas que el gobierno puede hacer con mi NDA. Pero ella dice que sí. Pero su mamá tiene un nombre muy común.

Constanza: En Chile, María González debe haber unas 7000. Todas se llaman María algo. Yo me llamo María. María Teresa, María Fernanda, etcétera.

Jimmy: Es lo mismo de John Smith en los Estados. Y por esa razón, si quieres conocer su mamá, necesitas hacerlo.

Y para mí, pienso que qué horrible si ella piensa que estoy fallecido. Pero estoy vivo.

Eliezer: Entonces, Jimmy se hizo la prueba de ADN en 2023.

Constanza: Para que uno entienda cuando te sale que tú compartes 50% con alguien, ese alguien es tu madre o tu padre. Si me sale 25 con alguien es un hermano de por parte de madre o de padre o hermano de tus padres. Pero seguimos muy cerca. Después se va la mitad, 12: primos hermanos, seis: primos de segundo, que se yo.

Silvia: La prueba de Jimmy arrojó una coincidencia. Era una pariente lejana, pero Jimmy no dudó en escribirle:

Jimmy: Hola, me llamo Jimmy y estoy buscando para María Angélica González.

Silvia: Ella le respondió que tienen una María Angélica González en la familia…

Jimmy: Y cuando ella dice que tenemos es en presente, no es en el pasado. Claro, yo pensé. Personas viven. Para mí fue por primera vez respirar. Es Oh, tengo. Tengo una verdad. Y solo 42 años de mentiras. En menos de 42 días, tengo la verdad.

Eliezer: Ya volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo. Antes de la pausa, Jimmy había descubierto que su mamá biológica estaba viva.

Eliezer: Por fin sentía que las piezas encajaban. Pero mientras para él, en Estados Unidos, era la confirmación de una intuición de años, para María Angélica, en el sur de Chile, significaba el derrumbe de la historia en la que había creído por más de cuatro décadas.

María Angélica González: En el año 2023, mayo, que recuerdo muy bien la fecha, que fue el 21 de mayo, me llama una prima. Yo estaba terminando de almorzar.

Silvia: Ella es María Angélica González, la mamá biológica de Jimmy. La prima que la llamó es la pariente lejana que le había aparecido a Jimmy en el test de ADN.

María Angélica: Y me dice acaso yo había tenido un hijo en el año 1980, el 31 de octubre, y quedé como helada. Helada. Por la fecha, el año y el día de nacimiento y yo dije. ¿Por qué me pregunta eso mi prima? ¿Qué sabe ella de mí? ¿Qué sabe ella de lo que yo he vivido? Y me viene inmediatamente el recuerdo de mi hijo, de mi bebé. Y me dice porque un joven te busca que dice que fue traficado. No le tomé mucho asunto. Yo dije esta está loca, le corté la comunicación porque yo dije no, esto ya esto no puede ser.

Eliezer: La prima estaba en contacto con Constanza del Río, entonces le avisó que María Angélica no le había creído. Constanza decidió llamarla ella misma.

Constanza: Y ahí la Angélica me dice esto es imposible, yo no he entregado a nadie en adopción.

María Angélica: Yo le dije, yo tuve un hijo, pero mi hijo falleció.

María Angélica: Me enojé con Constanza. Yo dije esto no es un juego, esto… ¿qué están haciendo? Y ella me dice, mira, escúchame, escúchame, no creas que tú eres la única persona que hoy en día sabe que tiene un hijo y que está vivo, que se lo dieron por muerto. Yo quería morirme.

Constanza: Nosotros siempre somos muy cautelosos de ir paso a paso. Contamos la verdad para todas partes, pero vamos de a paso, le digo María Angélica, hay que hacer ADN por si acaso, por si acaso, por si acaso.

Silvia: La prueba de ADN comprobó que María Angélica era la mamá de Jimmy.

La habían engañado en el hospital donde lo tuvo, de la misma forma que lo hicieron con miles de mujeres.

Eliezer: En ese año, el 80, María Angélica vivía en Santiago y trabajaba en la tienda de una amiga. Estaba ahí cuando empezó su trabajo de parto y la amiga la llevó al hospital más cercano.

María Angélica: Mi hijo nació vivo. Lo sentí llorar. Escuché que el médico dice, está bajo peso, hay que colocarlo en una incubadora.

Silvia: María Angélica dice que la llevaron a la sala de reposo, sola, sin su hijo.

María Angélica: Después me dieron de alta a mí, al segundo día, y me dicen que el niño quedaría hospitalizado porque se había puesto amarillito y que dentro de 48 horas yo podía retirarlo.

Eliezer: El bebé supuestamente tenía ictericia, una condición que es bastante común en recién nacidos.

Silvia: A los dos días, María Angélica lo fue a buscar.

María Angélica: Me dicen: Lamentamos, tu bebé falleció. Y yo no tenía palabras. Me volví loca de llanto. Llorar, llorar. Fui con mi amiga y mi amiga le dice cómo, por qué falleció. Me dijo No, porque el niño se puso amarillo y no sé, falleció. Y preguntó ella si lo entregaban para sepultarlo y le dijeron que no, cuando fallecían se desechaban. Recuerdo que llegué donde el asistente social que era dentro del hospital, que era como un laberinto. No recuerdo mucho porque realmente yo no tenía, no escuchaba lo que ella me decía. Simplemente yo firmé el documento de que mi hijo había fallecido. No me traje ningún documento porque no me entregaron nada, solamente me hicieron firmar unos papeles que yo firmé y listo.

María Angélica: No lo tuve en mi brazo, ni siquiera. Yo no le puse nombre. Sí, tenía varios nombres pero no se pudo concretar su nombre.

María Angélica: Pasó el tiempo. Fui sanándome, pero nunca dejé de sufrir, de llorar por mi hijo. Siempre me pregunté que por qué pasó eso. ¿Por qué? ¿Por qué se murió?

Eliezer: Constanza nos dijo que el cuento del bebé con ictericia que luego fallecía era común entre estas redes de tráfico de niños. También anestesiaban a las madres y luego les decían que sus hijos habían muerto en el parto.

Constanza: Después le decían, toma tus cosas y ándate, porque tu bebé se murió con una frialdad, sin ninguna contención, siendo muy violentos para que quedara en shock y generalmente la madre se iba.

Silvia: Hay casos de mujeres que cuentan que las trataban mal, las insultaban…

Constanza: Les decían pero cómo, segundo niño que tiene sin padre. Estamos hablando del año 70 y 80, tener un hijo sin padre era un pecado mortal. Chile es un país tradicional donde la Iglesia y la política van de la mano. Entonces, la empezaban a criticar que era una mala madre, que si ya el primero se le estaba muriendo de hambre, este se le iba a morir también de hambre y que lo entregara, que lo entregara, pero la empujaban a la entrega o la amenazaban. Si no entregaba el bebé, le quitaban el bebé y el otro niño.

Eliezer: Del otro lado estaban los padres adoptivos, que muchas veces no sabían que las adopciones eran ilegales. Como del engaño participaban doctores, jueces, funcionarios públicos y también autoridades y orfanatos religiosos, los procesos parecían legítimos y con documentación aparentemente en regla. Además, desde 1965, en Chile existía una ley que permitía las adopciones privadas. O sea, que las familias adoptantes podían acordar la adopción directamente con las familias biológicas o con intermediarios, como agencias de adopciones privadas, curas, médicos o abogados. No necesitaban ni siquiera pasar por un proceso judicial, podían formalizar la adopción ante un notario y listo.

Esa ley abrió la puerta para muchas irregularidades. Y aunque se derogó en 1988, la ley que la reemplazó aún tenía vacíos legales que permitieron que las adopciones ilegales siguieran. Recién en 1999 entró en vigencia una ley que regula muchísimo más el proceso.

Silvia: A la vez, países como Estados Unidos, Suecia, Francia, Italia y Alemania promovían la adopción de niños en el extranjero. Incluso, según diferentes investigaciones, para hacer posible estas adopciones, funcionarios de organismos de adopción de muchos de esos países se coludieron con agentes del Estado chileno o personas que no son funcionarios públicos, como los médicos y curas que estuvieron involucrados.

Muchas familias adoptivas pensaban que estaban ayudando a niños que habían sido abandonados… o salvándolos de la pobreza extrema.

Eliezer: Pasaron décadas para que en Chile se supiera que esto pasaba. De hecho, la verdad se empezó a revelar recién en el 2014, luego de un reportaje del medio CIPER, que detallaba cómo un cura y un doctor y exdiputado bastante conocidos en el país, eran parte de una red que engañaba a madres, diciéndole que sus hijos estaban muertos, para darlos en adopción.

Silvia: Ese es el mismo año que Constanza fundó Nos Buscamos. Y no ha sido fácil hacer este trabajo, porque lo que han revelado a algunos les incomoda.

Constanza: Lo que nosotros defendemos, esta fundación Nos Buscamos, es el derecho a la identidad, el derecho a saber. A saber todo: lo bueno y lo malo. Porque la gran mayoría de la sociedad, cuando un adoptado legal o un traficado ilegalmente comienza su búsqueda siendo un adulto grande, la gente les da, nos da su opinión que no solicitamos, que nos dicen pero para qué buscas si padre es el que cría y no el que pare, ¿para que buscas? Déjalo así vas a sufrir. Esto tiene que ver con un derecho, no con un capricho. Capricho de saber quién es mi madre biológica, qué fue lo que pasó, si pertenezco o no pertenezco a una etnia de mi país o etcétera. Esto es un derecho. Uno de los derechos de los niños es el derecho a la identidad y a la historia personal.

Eliezer: Por eso cuando Jimmy supo la verdad, él y su esposa vendieron su camioneta para poder pagar un viaje a Chile. Llegaron a Santiago en agosto del 2023 con sus hijas.

Silvia: Recuerda ver con ellas por primera vez la cordillera de Los Andes desde el avión. Aterrizar en Santiago…

Jimmy: Cuando el avión está en la tierra, por primera vez de toda mi vida, yo sentí: estoy en mi país, en mi casa.

Silvia: Al día siguiente iba a viajar con su familia a Valdivia, en el sur, donde vive María Angélica. Pero antes, ese día que llegaron, Constanza los acompañó a su hotel en Santiago.

Constanza: No habían pasado ni 40 minutos y llegaron dos hermanos de Jimmy que se pegaron el pique. O sea, se tomaron un bus porque ya no se pudieron aguantar la ansiedad, la angustia, la espera. Y yo me acuerdo que estábamos tomando un café, alcancé a sacar el teléfono, pero de suerte.

Constanza: Y se le tiró un hermano y a los 20 minutos se le tira a la hermana encima y son extremadamente parecidos.

Jimmy: Abrazamos. Besamos. Y nuestros niños, hijos, están cerca y son iguales. Son iguales. Es increíble.

Eliezer: Un día después, Jimmy por fin conoció a María Angélica.

Hay un video de ese momento.

Eliezer: Se ve a Jimmy sosteniendo a una de sus hijas con una mano y con la otra un ramo de flores. Va vestido con un traje azul y corbata.

Jimmy: Cuando estamos en la calle, en frente de la casa de ella, cuando ella está afuera, solo pienso que ella es tan pequeña. Y para mi es un duele grande. ¿Cómo puede hacer eso a ella? Una mujer tan, tan pequeña, tan amable. ¿Por qué? ¿Y quién puede hacerlo? Es tan difícil para mí.

Silvia: En el video se ve a María Angélica caminando hacia Jimmy con las dos manos sobre su cara. Cuando están suficientemente cerca, Jimmy le dice:

Audio de archivo, Jimmy Lippert-Thyden González: Hola Mamá.

Jimmy: Hola, mamá. nada más y abrazarle y ahh. La primera vez, 42 años. Perdimos 42 años. Y mi otro hermanos están acá. Y cuando entremos a la casa. Mi mamá tiene globos. 42 globos para para todos los años perdidos. Y toda la familia está acá, como un cumple.

Eliezer: Tus 42 cumpleaños.

Jimmy: Sí, sí.

María Angélica: Fue hermoso, hermoso. Abrazarlo, sentir que era mi mi, la parte del puzzle que faltaba. Nos amamos. No hay día que yo no le diga que lo amo con toda el alma y él también me llama. Mis nietas nos amamos mucho, mucho. Es una relación muy linda. Constantemente nos estamos haciendo llamadas video.

Silvia: La ONG de Constanza ha logrado más de 400 de estos encuentros desde el 2014. Después de la pausa, lo que ha hecho el Estado chileno luego de décadas de corrupción y la decisión que tomó Jimmy después de visitar Chile. Ya volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Constanza: Mira, a mí se me llena el alma de alegría cada vez que logramos hacer un reencuentro. A una persona decirle mira, tienes hermanos, pasó esto, no eres abandonado, fuiste robado. Porque es muy distinto saberse botado, abandonado que robado. ¿Se entiende? Te cambia completamente el piso. Te da vuelta la vida. Haces cambios de vida.

Silvia: A ella misma le pasó. A los 39 años, Constanza se enteró que había sido adoptada ilegalmente. En su caso, pasó poco antes de que empezara la dictadura y todo lo que vivió tratando de descubrir la verdad la llevó a crear Nos Buscamos.

Constanza: Fue tan impactante encontrar a mi familia biológica que hoy día yo renuncié a mi trabajo formal, que ganaba mucho dinero y me dedico 100% a esto y no tengo sueldo y aquí me las estoy arreglando como puedo pa eso, pa eso tengo herramientas y ahí vamos como lo hacemos. Pero el reencuentro es tan importante y además son tan pocas las personas que están trabajando en esto y el Estado no lo está haciendo. Por lo tanto, se necesitan muchas manos. Y hay mucha gente necesitando nuestro apoyo. Esa es la razón por la cual no solamente yo, sino que todos los voluntarios de Nos Buscamos y las otras organizaciones Connecting Roots, Hijos y Madres, todos trabajan por lo mismo por el derecho a la identidad y el derecho a darle voz a miles de mujeres de escasos recursos chilenas que no, que no, todavía no les creen que les robaron un bebé.

Eliezer: ¿A 35 años del retorno a la democracia, cuál crees que es la principal deuda del Estado chileno con los bebés robados que ahora son adultos, como tú dices, ya no son niños?

Constanza: El reconocimiento formal de los hechos como una verdad histórica. O sea, que el Estado de Chile, el presidente de Chile, reconozca esto, que el presidente Gabriel Boric reconozca formalmente esto como delitos de lesa humanidad con un decreto ley y que se levante una Comisión para que al menos censemos, contemos a las personas que sufrieron esto, porque ni siquiera tenemos el número real.

Silvia: El Estado chileno empezó a investigar las adopciones ilegales en el 2018. El juez asignado al caso, Jaime Balmaceda, pasó cinco años investigando más de mil denuncias… Hasta que en el 2024 salió en la prensa diciendo que no había encontrado ni un solo delito.

Constanza: O sea, para él que a una madre, como la mamá de Jimmy, le digan que su guagua, su bebé, murió en el parto y que aparezca vivo 42 años después, para él no es delito. Entonces uno se da cuenta ahí que no hay ninguna voluntad.

Eliezer: Balmaceda fue tan criticado por estas declaraciones, que terminó siendo reemplazado por otro juez a mediados del 2024.

El mismo año, el gobierno creó una mesa de trabajo para apoyar la investigación judicial. Pero la prensa ha revelado que los funcionarios asignados son pocos y no trabajan exclusivamente para la investigación. También se anunció un acuerdo con Suecia para compartir información sobre los casos.

Silvia: Aun así, a siete años del comienzo de la investigación, no hay un solo condenado.

Eliezer: Constanza, hablamos de esto ahora porque es una de las grandes deudas de la dictadura, ¿no? Pero tal como tú me cuentas, estamos hablando de un aparato muy grande que incluso empezó desde antes, ¿no? ¿Se ha seguido viendo casos de adopciones ilegales en democracia?

Constanza: Sí, lamentablemente sí. Cuando cae el la dictadura comienza el primer gobierno democrático que fue con don Patricio Aylwin. Y se establecen, obviamente, entidades estatales que habían desaparecido, por ejemplo el Congreso.

Silvia: Además crearon entidades estatales para apoyar y proteger a las familias. Pero también siguió operando un organismo que en dictadura había sido acusado de facilitar las adopciones ilegales: el Servicio Nacional del Menor, más conocido como Sename.

Constanza: Y Sename venía con la misma gente que trabajaba antes con niños. Por lo tanto, el tráfico de niños continuó, continuó durante mucho tiempo hasta el 2014, que fue cuando nosotros nacemos como organización y empezamos a reunirnos con entidades públicas y les empezamos a poner ojo y empezamos a hablar en La Haya y viajábamos y qué sé yo. Y en 2014 recién paran las adopciones internacionales en forma desmedida.

Silvia: Constanza dice “desmedida” porque saben que esto sigue pasando. No son miles de niños al año, como antes, pero sí decenas.

Silvia: La visita que hizo Jimmy a Chile en 2023 fue la culminación de una búsqueda de años. Pero también fue el comienzo de algo más. Mientras estuvo en el país, Jimmy fue a la Policía de Investigaciones a denunciar lo que había pasado.

Jimmy: Después de todas las citas con los oficiales de gobierno. Yo sé, no hay nadie va a ayudar a las madres, las mamás y los hijos, nadie. Y el gobierno no hace nada para reparar eso. Y pienso que necesito hacer una cosa.

Eliezer: Jimmy volvió a estudiar. Ya era abogado, pero quiso sacar un certificado de derechos humanos internacionales. También fundó una organización para ayudar en los reencuentros de otros chilenos que como él fueron dados en adopción a familias en Estados Unidos.

Silvia: En julio de 2024, Jimmy volvió a Chile para demandar al Estado chileno por secuestro. Y ahora se hace llamar Jimmy Lippert-Thyden González.

Daniela Cruzat: Este episodio fue producido por mí, Daniela Cruzat. Lo editaron Silvia y Eliezer. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido y la música son de Elías González.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Mariana Zúñiga, Nausícaa Palomeque, Samantha Proaño, Natalia Ramírez, Juan David Naranjo Navarro, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Desirée Yépez y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres abrir el hilo para informarte en profundidad sobre los temas de cada episodio, puedes suscribirte a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

*This English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and subsequently reviewed and edited by our editorial team for accuracy and clarity.

Silvia Viñas: Jimmy’s parents never hid from him that he was adopted. They knew they couldn’t have children… and decided to adopt him to give a baby a good life.

Jimmy: It’s a dream for them. But for me, it’s a bit different because I know I’m in a family full of love and with many opportunities, but the truth is… I’m not American.

Eliezer: Jimmy grew up in Virginia, USA. He bore the last name Lippert-Thyden, but from a young age, he knew his roots weren’t in the United States. He was born in Chile. And he felt different. First, because he felt no one looked like him.

Jimmy: I’m in a neighborhood without Latinos. There are no Latinos in my community, in my school.

Silvia: He learned Spanish because he took a course for a year…

Jimmy: All my life, when people say, ‘Where are you from?’ I never said, ‘I’m from the United States. I’m always from Chile.

Eliezer: Even though he had never been there. Jimmy told us his adoptive parents said his biological mother had given him up for adoption because she wanted a better life for him.

Jimmy: And for this reason, with all love, you are adopted to another country. But for me, it’s not that simple.

Silvia: He felt that something didn’t fit in that story.

Jimmy: I always felt that… where is the evidence of that?

Silvia: Jimmy wondered: if his biological mother had wanted the best for him, why hadn’t she left a letter or something explaining her decision?

Jimmy: For evidence of love. For evidence of the story. But I have nothing.

Eliezer: It took a long time before Jimmy confirmed his hunch. When he was 31 years old, his adoptive mother showed him his adoption papers.

Silvia: There, in a folder with different documents, he found several versions of why he had been given up. But they were contradictory. For example, one said that it was unknown who his mother was, but another stated he had no living relatives. And one mentioned that his mother had given him up for adoption when he was two years old.

Jimmy: And for this reason, I think there is something more. I don’t know what it is. And for me, it is so difficult to visit another country, and it’s a lot of money to do it.

Eliezer: Also, at that time, in 2011, Jimmy was in the navy and he says it wasn’t easy to get permission to travel.

Silvia: But he continued with the doubt. More than a decade later, in April 2023, when Jimmy was 42 years old, his wife stumbled upon a story in the press…

Jimmy: My wife says you need to read this. It’s incredible.

Jimmy: And in that news, a man, Scott Lieberman…

Archive audio, host: Scott Lieberman says he always knew he was adopted and that he was born in Chile. What he didn’t know was the whole truth about how the adoption occurred. A few months ago, he found out that in the seventies and eighties, there were many cases of babies stolen in Chile and sold to adoption agencies.

Eliezer: Media outlets around the world shared Scott Lieberman’s story because he managed to reunite with part of his family in Chile and prove that he had been stolen and given up for illegal adoption.

Jimmy: I remember when I read that, I just think that, oh, how horrible. But I think, if that’s my story, it’s simpler.

Silvia: Simpler, says Jimmy, because it would explain why there were so many different versions in his adoption papers.

Eliezer: He thought those contradictions were meant to hide the truth: that he had been stolen during the military dictatorship, like over 20,000 other children. He was not wrong.

Eliezer: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: And I’m Silvia Viñas.

This week marks 35 years since the return to democracy in Chile, and the State reaches this anniversary with several historical debts. Among them, the theft and delivery of babies to foreign families: a system of complicity that managed the illegal adoption of tens of thousands of Chilean children for more than four decades, and was legitimized and shielded by the dictatorship.

Victims’ organizations denounce that, since the return to democracy, no government has taken charge of formally recognizing these events, nor has sought a form of justice and reparation. Moreover, many cases demonstrate that the trafficking networks continued operating after the Pinochet regime.

Today, a story of impunity and the right to identity that puts Chile in front of the mirror.

It’s March 14, 2025.

Eliezer: When Jimmy read the news about Scott Lieberman, the man who had reunited with his Chilean family, he saw information that might help him clarify his story.

Silvia: Lieberman had worked with a Chilean NGO called Nos Buscamos. They help families separated by child trafficking reunite. Jimmy went to their website and filled out a form.

Jimmy: With all my story and with photos of all my documents. And I think maybe they will call me maybe in six months, maybe they will work on my case, I don’t know, but it’s possible.

Constanza del Río: We, immediately, like 20 minutes later, sent him an email telling him to download WhatsApp so we could talk.

Eliezer: She is Constanza del Río, the creator and director of the NGO Nos Buscamos.

Jimmy: Constanza is just like me. She can’t wait for anything. I love that about her.

Constanza: And half an hour to an hour later, we were already talking and the first thing he tells me is I want to rule out, I want you to confirm that I was not trafficked, because it’s very frightening to realize that it’s not the story you were told all your life.

Constanza: Jimmy. It’s case 5,482 in our database. Today we already have more than 7,000.

Silvia: The Investigative Police of Chile estimate that between the 1950s and the 90s, more than 20,000 babies and children were separated from their families and given up for illegal adoption. A good part was given to foreign families. Yes, that number includes more than 20 years before the Pinochet dictatorship, which was between 1973 and 1990.

Eliezer: But during the dictatorship, these illegal adoptions intensified.

Constanza: It was important to remove as many children from Chile as possible, one to get rid of them and two to better control the people. It was a form of repression, a way to manage and a way to avoid a burden also for the State.

Eliezer: According to researchers, the adoption of Chilean children from abroad allowed the regime to save public spending and control population growth. But in addition, Constanza says that the dictatorship offered an ideological justification and made it impossible for a young, resourceless mother to claim against the State or the institutions involved.

Silvia: Children were trafficked under a network of public and private institutions that operated under deception. They were doctors, midwives, social workers, priests, public officials, judges, and lawyers who orchestrated everything. According to the organization Nos Buscamos and other research, they charged up to tens of thousands of dollars per child.

Constanza: It was always, always, always the same target: women of scarce resources. Minors in many cases. Illiterate, etc. And the traffickers of babies, the social workers from Chile’s public hospitals would target all the women who entered, the one who came with the husband, with the mom, with the mother-in-law, with a sister. Not her. The one who was very empowered, the one who was very loud and very bossy, neither. The one who was shy, the one who was scared, the one who was anguished. That was the target. And there they swooped down like crows.

Eliezer: In this context, Jimmy was adopted. And he was about to find out.

Silvia: Constanza’s team at Nos Buscamos started investigating his case the same day Jimmy filled out the form with the information he had about his adoption.

Constanza: What is normally done with adoptees is: they are registered in our database, we look for their background to see if they have the RUT number.

Silvia: RUT. That’s what they call the identity number in Chile. The DNI in other countries. They give it to babies when they are registered at the Civil Registry.

Eliezer: And Jimmy had this number among his papers. That was very useful for the Nos Buscamos team because that way, they could quickly verify if he had been trafficked.

Constanza: Why? Because for legal adoptees, what should happen is that their original name and original RUT are erased from the Civil Registry to make way for the new identity in Italy or here in Chile or in the United States, or wherever.

Silvia: When they entered Jimmy’s identity number into public databases, it was still there… But it didn’t have the same name.

Constanza: A few minutes later, because we are a big team of researchers, we got in touch with Jimmy and told him straight away. Unfortunately, I have to confirm that yes, you are part of those trafficked.

Eliezer: Wow! I mean, they told him the same day, a few minutes after the call.

Constanza: The same day.

Eliezer: The next step was for someone from Nos Buscamos to go to the Civil Registry to request Jimmy’s original birth documents.

Constanza: And neither mother nor father appeared. Nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing. Everything like that. Everything hidden. When that happens, it’s because it’s trafficking.

Silvia: But in the papers that Jimmy had passed on, there was useful data, such as his date of birth, October 31, 1980. There was also the address of an orphanage in Santiago, although it’s not clear where he spent his first years of life, because he was supposedly adopted when he was two years old.

Constanza: From all the documents that we had managed to interpret. We had a clue that the mother was named María González.

Constanza: If Jimmy hadn’t done a DNA test, he had to do it now.

Jimmy: And I think I don’t want to do it because I’m a criminal defense lawyer. And I know all the things the government can do with my DNA. But she says yes. But his mom has a very common name.

Constanza: In Chile, there must be about 7,000 María González. They all have María something. My name is María. María Teresa, María Fernanda, etc.

Jimmy: It’s the same as John Smith in the States. And for that reason, if you want to meet your mom, you need to do it.

And for me, I think how horrible it would be if she thinks I’m deceased. But I’m alive.

Eliezer: So, Jimmy took the DNA test in 2023.

Constanza: So that one understands when it comes out that you share 50% with someone, that someone is your mother or your father. If I get 25 with someone, it’s a sibling on the mother’s or father’s side or a sibling of your parents. But we continue to be very close. After that, it goes half, 12: first cousins, six: second cousins, you know.

Silvia: Jimmy’s test yielded a match. It was a distant relative, but Jimmy didn’t hesitate to write to her:

Jimmy: Hello, my name is Jimmy, and I am looking for María Angélica González.

Silvia: She replied that they have a María Angélica González in the family…

Jimmy: And when she says that we have her, it’s in the present, not in the past. Sure, I thought. People live. For me, it was my first time to breathe. Oh, I have it. I have a truth. And only 42 years of lies. In less than 42 days, I have the truth.

Eliezer: We’ll be right back.

Silvia: We’re back on El Hilo. Before the break, Jimmy had discovered that his biological mother was alive.

Eliezer: Finally, he felt that the pieces fit. But while for him, in the United States, it was the confirmation of an intuition of years, for María Angélica, in the south of Chile, it meant the collapse of the story she had believed for more than four decades.

María Angélica González: In the year 2023, May, which I remember very well, it was May 21, a cousin called me. I was finishing lunch.

Silvia: She is María Angélica González, Jimmy’s biological mother. The cousin who called her is the distant relative who had appeared to Jimmy in the DNA test.

María Angélica: And she asks me if I had had a son in 1980, on October 31, and I was frozen. Frozen. Because of the date, the year, and the day of birth, I said: Why is my cousin asking me this? What does she know about me? What does she know about what I have lived? And immediately I remember my son, my baby. And she tells me because a young man is looking for you who says he was trafficked. I didn’t pay much attention. I said she’s crazy, I cut off communication because I said no, this can’t be.

Eliezer: The cousin was in contact with Constanza del Río, so she let her know that María Angélica hadn’t believed her. Constanza decided to call her herself.

Constanza: And there, Angélica tells me this is impossible, I haven’t given anyone up for adoption.

María Angélica: I told her, I had a son, but my son died.

María Angélica: I got angry with Constanza. I said this is not a game, this… what are you doing? And she tells me, look, listen to me, listen, don’t think you’re the only person who nowadays knows they have a son and that he’s alive, that they gave him up for dead. I wanted to die.

Constanza: We are always very cautious to go step by step. We tell the truth to everyone, but we go step by step. I tell María Angélica, we have to do DNA just in case, just in case, just in case.

Silvia: The DNA test proved that María Angélica was Jimmy’s mom. They had deceived her in the hospital where she had him, in the same way they did with thousands of women.

Eliezer: That year, in the 80s, María Angélica lived in Santiago and worked at a friend’s store. She was there when she started her labor, and the friend took her to the nearest hospital.

María Angélica: My son was born alive. I felt him cry. I heard the doctor say, he’s underweight, we need to put him in an incubator.

Silvia: María Angélica says they took her to the resting room, alone, without her son.

María Angélica: Then they discharged me, on the second day, and they tell me that the baby would remain hospitalized because he had turned a little yellow and that within 48 hours I could pick him up.

Eliezer: The baby supposedly had jaundice, a condition that is quite common in newborns.

Silvia: Two days later, María Angélica went to pick him up.

María Angélica: They tell me: We are sorry, your baby has died. And I had no words. I went crazy crying. Cry, cry. I went with my friend, and my friend asked them how? Why did he die?. They said, because the baby turned yellow and I don’t know, he died. And she asked if they released him for burial, and they told her no, when newborns died they were discarded. I remember I went to the social worker who was inside the hospital, which was like a labyrinth. I don’t remember much because I really didn’t, I didn’t hear what she was telling me. I just signed the document that my son had died. I didn’t bring any documents because they didn’t give me anything, they just made me sign some papers that I signed and that’s it.

María Angélica: I didn’t hold him in my arms, not even. I didn’t name him. Yes, I had several names but couldn’t choose his name.

María Angélica: Time passed. I healed, but I never stopped suffering, crying for my son. I always wondered why it happened. Why? Why did he die?

Eliezer: Constanza told us that the story of the baby with jaundice who then died was common among these child trafficking networks. They also anesthetized the mothers and then told them that their children had died during childbirth.

Constanza: Then they would say, take your things and leave, because your baby died with such coldness, without any support, being very violent so that the mother would be in shock and generally the mother would leave.

Silvia: There are cases of women who say they were treated badly, insulted…

Constanza: They would say but how, second child you have without a father. We are talking about the ’70s and ’80s, having a child without a father was a mortal sin. Chile is a traditional country where the Church and politics go hand in hand. So, they started criticizing her that she was a bad mother, that if the first one was already starving, this one was going to die of hunger too and that she should give him up, that she should give him up, but they pushed her to give him up or threatened her. If she didn’t give up the baby, they took the baby and the other child.

Eliezer: On the other side were the adoptive parents, who often didn’t know the adoptions were illegal. As the deception involved doctors, judges, public officials, and also religious authorities and orphanages, the processes seemed legitimate and with apparently proper documentation. Moreover, since 1965, in Chile, there was a law that allowed private adoptions. That is, adoptive families could agree on the adoption directly with the biological families or with intermediaries, such as private adoption agencies, priests, doctors, or lawyers. They didn’t even need to go through a judicial process, they could formalize the adoption before a notary and that’s it.

This law opened the door to many irregularities. And although it was repealed in 1988, the law that replaced it still had legal loopholes that allowed illegal adoptions to continue. Only in 1999 did a law come into effect that regulates the process much more.

Silvia: At the same time, countries like the United States, Sweden, France, Italy, and Germany promoted the adoption of children abroad. Even, according to different investigations, to make these adoptions possible, officials from adoption agencies of many of those countries colluded with agents of the Chilean State or people who are not public officials, such as doctors and priests who were involved.

Many adoptive families thought they were helping children who had been abandoned… or saving them from extreme poverty.

Eliezer: It took decades for it to be known in Chile that this was happening. In fact, the truth began to be revealed only in 2014, after a report by the media outlet CIPER, which detailed how a priest and a doctor and former congressman quite well-known in the country, were part of a network that deceived mothers, telling them that their children were dead, to give them up for adoption.

Silvia: That’s the same year that Constanza founded Nos Buscamos. And it has not been easy to do this work, because what they have revealed makes some people uncomfortable.

Constanza: What we defend, this foundation Nos Buscamos, is the right to identity, the right to know. To know everything: the good and the bad. Because the vast majority of society, when a legally adopted or illegally trafficked person begins their search being an adult, people give us, give us their unsolicited opinion, they tell us but why do you search if a father is the one who raises and not the one who gives birth, why do you search? Leave it like that you’re going to suffer. This has to do with a right, not with a whim. Whim of knowing who my biological mother is, what happened, whether I belong or do not belong to an ethnicity of my country or etc. This is a right. One of the rights of children is the right to identity and to personal history.

Eliezer: That’s why when Jimmy knew the truth, he and his wife sold their truck to be able to pay for a trip to Chile. They arrived in Santiago in August 2023 with their daughters.

Silvia: Remember seeing with them for the first time the Andes mountain range from the plane. Landing in Santiago…

Jimmy: When the plane is on the ground, for the first time in my whole life, I felt: I’m in my country, at home.

Silvia: The next day he was going to travel with his family to Valdivia, in the south, where María Angélica lives. But before, the day they arrived, Constanza accompanied them to their hotel in Santiago.

Constanza: It hadn’t been 40 minutes and two brothers of Jimmy’s had shown up. I mean, they took a bus because they couldn’t stand the anxiety, the anguish, the wait anymore. And I remember we were having a coffee, I luckily managed to get out the phone.

Constanza: And one brother threw himself at him and 20 minutes later his sister threw herself on top of him and they are extremely similar.

Jimmy: We hugged. We kissed. And our children are close and look alike. It’s incredible.

Eliezer: A day later, Jimmy finally met María Angélica.

There’s a video of that moment.

Eliezer: You see Jimmy holding one of his daughters with one hand and with the other a bouquet of flowers. He’s dressed in a blue suit and tie.

Jimmy: When we are on the street, in front of her house, when she’s outside, I just think that she’s so small. And for me, it’s a big pain. How can they do that to her? A woman so so small, so kind. Why? And who can do it? It’s so hard for me.

Silvia: In the video, you see María Angélica walking towards Jimmy with both hands on her face. When they are close enough, Jimmy tells her:

Archive audio, Jimmy Lippert-Thyden González: Hello Mom.

Jimmy: Hello, mom. just nothing more than hugging her and ahh. The first time, 42 years. We lost 42 years. And my other brothers are here. And when we enter the house. My mom has balloons. 42 balloons for all the lost years. And the whole family is here, like a birthday.

Eliezer: Your 42 birthday.

Jimmy: Yes, yes.

María Angélica: It was beautiful, beautiful. To hug him, to feel that he was my my, the missing piece of the puzzle. We love each other. There isn’t a day that I don’t tell him that I love him with all my soul and he also calls me. My granddaughters and I love each other very much, very much. It’s a very nice relationship. We are constantly making video calls.

Silvia: Constanza’s NGO has achieved more than 400 of these reunions since 2014. After the break, what the Chilean State has done after decades of corruption and the decision that Jimmy made after visiting Chile. We’ll be back.

Eliezer: We’re back on El Hilo.

Constanza: Look, my soul fills with joy every time we manage to make a reunion. To tell a person look, you have siblings, this happened, you were not abandoned, you were stolen. Because it’s very different to know yourself thrown away, abandoned than stolen. Do you understand? It completely changes the ground. It turns your life around. You make life changes.

Silvia: It happened to her herself. At 39 years old, Constanza found out she had been illegally adopted. In her case, it happened just before the dictatorship started and everything she went through trying to discover the truth led her to create Nos Buscamos.

Constanza: It was so shocking to find my biological family that today I quit my formal job, which paid a lot of money, and I dedicate myself 100% to this and I have no salary and here I am managing as I can for that, for that I have tools and there we go as we do it. But the reunion is so important and besides there are so few people working on this and the State is not doing it. Therefore, many hands are needed. And there are many people needing our support. That’s the reason why not only me, but all the volunteers from Nos Buscamos and other organizations Connecting Roots, Sons and Mothers, all work for the same for the right to identity and the right to give voice to thousands of Chilean women of scarce resources who still don’t believe that a baby was stolen from them.

Eliezer: 35 years after the return to democracy, what do you think is the main debt of the Chilean State with the stolen babies who are now adults, as you say, no longer children?

Constanza: The formal recognition of the facts as a historical truth. That is, that the State of Chile, the president of Chile, recognizes this, that President Gabriel Boric formally recognizes this as crimes against humanity with a decree law and that a Commission is set up so that at least we can census, count the people who suffered this, because we don’t even have the real number.

Silvia: The Chilean State began investigating illegal adoptions in 2018. The judge assigned to the case, Jaime Balmaceda, spent five years investigating more than a thousand complaints… Until in 2024 he came out in the press saying that he had not found a single crime.

Constanza: I mean, for him that a mother, like Jimmy’s mom, is told that her baby, her baby, died in childbirth and that he appears alive 42 years later, for him it’s not a crime. So one realizes there that there is no will.

Eliezer: Balmaceda was so criticized for these statements, that he ended up being replaced by another judge in the middle of 2024.

That same year, the government created a working table to support the judicial investigation. But the press has revealed that the officials assigned are few and do not work exclusively for the investigation. An agreement was also announced with Sweden to share information about the cases.

Silvia: Even so, seven years after the start of the investigation, there is not a single convict.

Eliezer: Constanza, we talk about this now because it is one of the great debts of the dictatorship, right? But as you tell me, we are talking about a very large apparatus that even started before, right? Have there continued to be cases of illegal adoptions in democracy?

Constanza: Yes, unfortunately yes. When the dictatorship fell, the first democratic government began with Mr. Patricio Aylwin. And obviously, state entities that had disappeared were established, for example, the Congress.

Silvia: They also created state entities to support and protect families. But an organism that had been accused of facilitating illegal adoptions during the dictatorship also continued to operate: the National Service for Minors, better known as Sename.

Constanza: And Sename came with the same people who worked before with children. Therefore, child trafficking continued, continued for a long time until 2014, which was when we were born as an organization and we started to meet with public entities and we started to keep an eye on them and we started to talk in The Hague and we traveled. And in 2014, international adoptions finally stopped in an excessive way.

Silvia: Constanza says “excessive” because they know that this still happens. Not thousands of children a year, like before, but yes, dozens.

Silvia: Jimmy’s visit to Chile in 2023 was the culmination of a years-long search. But it was also the beginning of something more. While he was in the country, Jimmy went to the Investigative Police to report what had happened.

Jimmy: After all the appointments with government officials. I know, no one is going to help the mothers, the moms and the children, no one. And the government does nothing to repair that. And I think I need to do something.

Eliezer: Jimmy went back to school. He was already a lawyer, but he wanted to get a certificate in international human rights. He also founded an organization to help in the reunions of other Chileans who, like him, were given up for adoption to families in the United States.

Silvia: In July 2024, Jimmy returned to Chile to sue the Chilean state for kidnapping. And now he goes by Jimmy Lippert-Thyden González.

Daniela Cruzat: This episode was produced by me, Daniela Cruzat. It was edited by Silvia and Eliezer. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. The sound design and music are by Elías González.

The rest of the El Hilo team includes Mariana Zúñiga, Nausícaa Palomeque, Samantha Proaño, Natalia Ramírez, Juan David Naranjo Navarro, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Desirée Yépez, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El Hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask you to join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donate and help us with a donation.

If you want to understand in depth about the topics of each episode, you can subscribe to our newsletter at elhilo.audio/boletin

We send it every Friday.

You can also follow us on our social media. We are on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook, and Threads. You can find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share the episodes.

Thank you for listening.