Aborto

México

Abortos fortuitos

Emergencia obstétrica

Homicidio en razón de parentesco

Infanticidio

Despenalización del aborto

Luciana Wainer

En México el aborto está despenalizado a nivel federal, pero hay mujeres que enfrentan penas de hasta 60 años de cárcel después de tener una emergencia obstétrica. Algunas son juzgadas por delitos como homicidio en razón de parentesco, infanticidio y hasta por omisión de cuidados. En este episodio hablamos con la periodista Luciana Wainer, autora del libro ‘Fortuito: el otro lado de la criminalización del aborto en México’. Luciana investigó durante años estos casos, y su trabajo revela cómo en algunos lugares de México las autoridades locales usan distintas figuras penales para criminalizar, perseguir y encarcelar a las mujeres que tienen abortos involuntarios o emergencias obstétricas.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Silvia Viñas -

Edición

Eliezer Budasoff -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción digital

Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elias González -

Música

Elias González -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

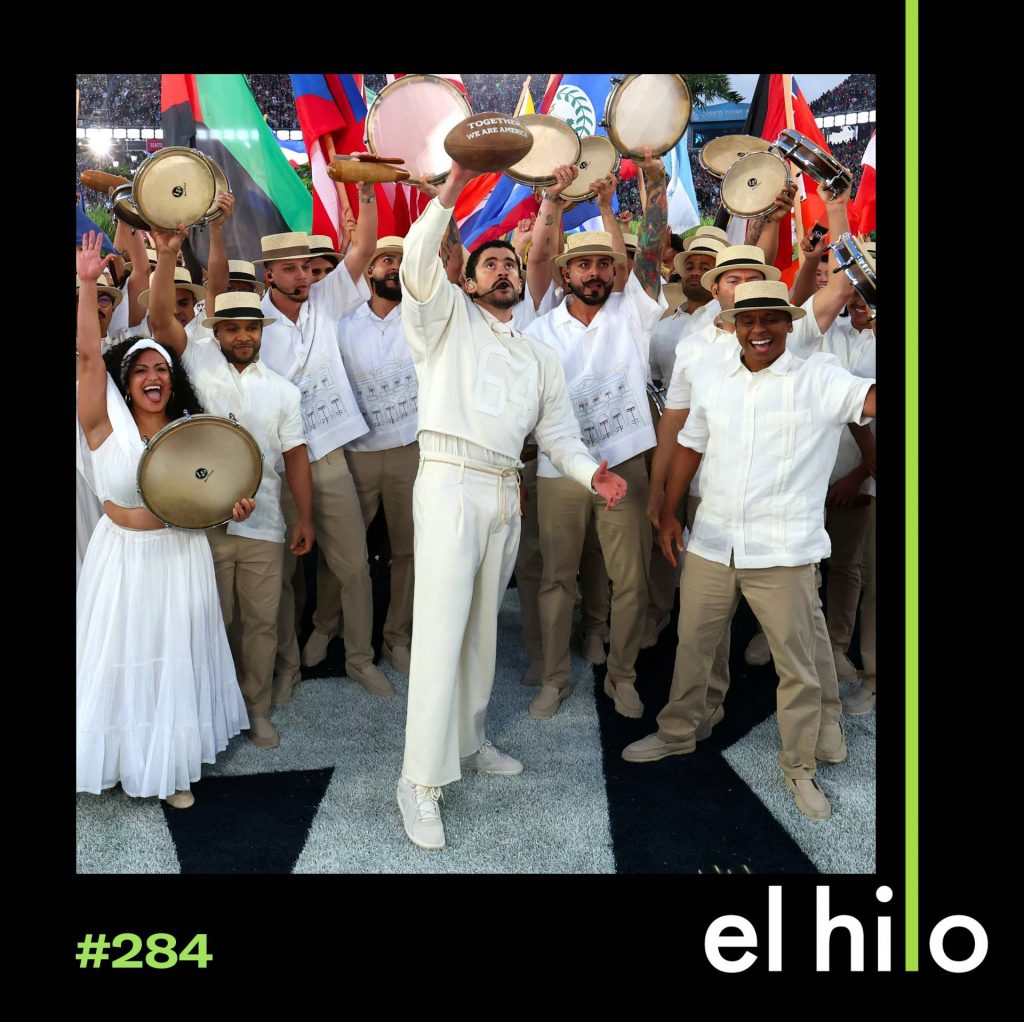

Fotografía

Getty Images / Alfredo Estrella

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Eliezer: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia Viñas: Y yo soy Silvia Viñas. En México, hay mujeres que enfrentan penas parecidas a las de criminales por abortar. Algunas, luego de tener abortos involuntarios.

Eliezer: Esto, en un país que hace unos años estableció un precedente importante en América Latina para los derechos reproductivos. Recordemos que la Suprema Corte de Justicia despenalizó el aborto a nivel federal en el 2021 y en 2023 declaró inconstitucional su prohibición. En otras palabras: declaró inconstitucional criminalizar la interrupción de un embarazo.

Silvia: Pero eso no significó que automáticamente el aborto sería legal en todo el país. La situación varía mucho de estado a estado. Más de 20 lo han despenalizado en sus constituciones, pero una docena aún lo tipifica como delito. Hoy, a pesar de la despenalización del aborto a nivel federal, en algunos lugares de México las autoridades locales usan distintas figuras penales para criminalizar, perseguir y encarcelar a mujeres que tienen abortos involuntarios o emergencias obstétricas.

Es 12 de septiembre de 2025.

Silvia: Luciana, hace unos años, con la decisión de la Suprema Corte, México se convirtió como en un ejemplo, digamos, en la región, ¿no? Y tú empezaste tu investigación sobre la criminalización del aborto antes de eso. Pero la publicaste después, en 2024. Me gustaría empezar con una pregunta, como, bastante general, pero. ¿Por qué te parece importante resaltar estos casos de criminalización del aborto en el México de ahora?

Luciana Wainer: Pues justo lo que suele ocurrir, digamos, en México pero en todos lados, es que finalmente el marco legal es solo el principio. Es solo lo primero que se transforma y que no necesariamente hace una transformación ni automática, ni completa, ni rápida en la vida de las personas, en la vida de las mujeres y personas gestantes, en este caso en particular.

Eliezer: Luciana Wainer es una periodista argentina que lleva más de una década en México. Hablamos con ella porque el año pasado publicó un libro que se llama Fortuito: el otro lado de la criminalización del aborto en México.

Luciana: Los cambios legales son solo una parte. Son solo un inicio para hacer una transformación real. El cambio cultural, la despenalización cultural, eso lleva muchísimo más tiempo, y creo que mientras eso no ocurra, los casos de criminalización o estigmatización o persecución van a seguir ocurriendo en nuestro país.

Silvia: Luciana empezó a investigar la criminalización del aborto desde un ámbito académico, mientras hacía una maestría.

Luciana: Cuando empiezo la investigación, mi objetivo era hablar de la criminalización del aborto per se. Es decir, quizás tener un número mucho más certero de las personas, de las mujeres que estaban encarceladas por el delito de aborto. Cómo estaba la situación en el país. Lo que me pasó fue que me empecé a dar cuenta que cuando empiezo a investigar sobre el delito de aborto en particular no encontraba casi nada. Le mandaba solicitudes de información y entonces me respondían de los estados, pues, que no había mujeres encarceladas, que había muy poquitas, que había hombres, por ejemplo, porque era personal de la salud, que había asistido abortos. Pero no encontraba yo… Había algo como que no me cerraba en ese sentido, porque yo sabía que la criminalización estaba ahí.

Eliezer: Una de las fuentes de Luciana durante esta investigación fue Verónica Cruz. Es activista, abogada, defensora de derechos humanos, y directora de Las Libres, una organización que promueve y defiende los derechos de las mujeres desde el estado de Guanajuato.

Luciana: Ella es la la primera que me dice oye, “pues mira, de aborto no, no tanto. Pero sí tengo casos de homicidio en razón de parentesco”. Y entonces ahí fue la primera vez que yo escuché eso y yo no entendía la relación que había. Yo decía. ¿Pero cómo? Y ella me dice, “bueno, sí, es que muchas mujeres con emergencias obstétricas, con partos prematuros, con abortos fortuitos, terminan encarceladas, pero no por el delito de aborto, sino por el delito de homicidio, homicidio en razón de parentesco”. Y entonces, cuando escucho eso, a mí me parece, la verdad, tan escandaloso, que pienso que tenía, que era un caso aislado, ¿no? Que era un caso que ella había acompañado de estas cosas que a veces ocurren. Y empiezo a tirar como de ese hilito, de esa información. Y hablando con colegas, de repente un colega periodista me dice, “yo cubrí un caso hace algunos años”, etcétera, etcétera. Y hablando con otro y otra organización… Y entonces empiezo a mandar solicitudes de información y me doy cuenta, digamos, que no es una situación generalizada, pero sí sistemática de criminalización del aborto, hacerlo a través de este tipo penal. Y claro, eso trae por supuesto, muchísimas, muchísimas complicaciones a la hora de rastrear los casos, a la hora de contabilizarlos, a la hora de mapearlos en el país. Y para las mujeres, sin lugar a dudas. Antes que nada, para ellas la diferencia de ser señalada o sentenciada por aborto a ser señalada o sentenciada por homicidio es una diferencia abismal.

Silvia: Sí, quiero desglosar un poquito varias cosas que has mencionado. Primero esta palabra, “fortuito”, ¿no? Se escucha “emergencia obstétrica”… Explícanos un poco para que quede claro qué es un aborto fortuito.

Luciana: Esa palabra cuando estaba eligiendo el título del libro fue una gran discusión con las editoras y demás, porque fue interesante. Fíjate que en realidad el concepto de parto fortuito desde el periodismo lo teníamos… Pues no lo usábamos para nada. Y se empieza a usar a raíz de uno de estos casos. Se empieza a usar a raíz del caso de Dafne McPherson

Audio de archivo, periodista: Tuvo un parto fortuito sin siquiera saber que estaba embarazada.

Luciana: Que tiene un parto fortuito en el baño de un centro comercial. Ella es criminalizada, ella es perseguida.

Audio de archivo, periodista 1: La joven fue acusada de homicidio agravado en contra de su hija recién nacida, y fue sentenciada a 16 años de cárcel.

Audio de archivo, periodista 2: Hablamos con ella y nos narró lo sucedido.

Audio de archivo, Dafne: Me quitaron mi vida. Me quitaron la oportunidad de estar con mi hija, de estar con mi familia.

Luciana: Y pasa tres años en un penal en Querétaro. Y ese concepto lo aprendimos ahí y eso me parecía muy, muy importante. El uso del lenguaje, en realidad en todos estos casos es muy importante y ocurre incluso en las búsquedas que hacemos en Internet. Lo primero que hacemos, nos metemos a ver cuántos casos hay o dónde. Y yo me encontraba con que, claro, los medios de comunicación habíamos hecho las coberturas nombrando estos casos de forma completamente errónea, desde decirle bebé al producto, madre a la mujer que estaba teniendo una emergencia obstétrica.

Eliezer: Hay una carga emocional detrás de “bebé” y “madre”. Y no son palabras precisas para usar en estos casos. Decir “producto”, como “producto de la gestación”, le quita esa carga. Es un término médico, científico.

Luciana: Y había justo estas, digamos, confusiones entre aborto, aborto fortuito, parto fortuito, emergencia obstétrica. A ver, el término fortuito implica que, digamos, no es buscado, no es doloso, es aleatorio. Y en ese sentido un parto fortuito tiene que ver con tener un parto en un lugar, o sea, primero, que no se estaba esperando. Y es un lugar fuera del hospital que no está preparado para eso, con todas las implicaciones que eso tiene. Y estas mujeres lo que ocurre normalmente es que el Estado falla dos veces muy rápido. La primera es no atender la emergencia de salud, que es una obligación que tiene el Estado y después de eso criminaliza a las mujeres. Lo toma desde el lado penal. Entonces fortuito, me parecía como que englobaba, ¿no? Un poco el alma y donde, de donde nacía toda esta situación.

Silvia: O sea, entonces, a ver, encontraste que las mujeres no estaban siendo encarceladas por el delito de aborto, sino por homicidio, como si fueran asesinas. ¿No? ¿Cómo es que pasa eso?

Luciana: Sí, justo. Porque además. Claro, para ese momento y ahora mucho más, el delito de aborto no alcanza prisión en nuestro país. Había solo una entidad cuando yo empecé la investigación que todavía alcanzaba prisión a raíz de los cambios que hubo en el sistema judicial. Pero claro, la primera diferencia entre el aborto y el homicidio son la cantidad de años de prisión. En el caso del aborto, aunque te encuentren culpable, no alcanzas prisión, no pisas la prisión. Y en el delito de homicidio estamos hablando de 10, 20, 30 hasta 50 años, pues. Entonces esa es la diferencia más brutal.

Eliezer: Esto significa que para poder llegar a una cifra de mujeres encarceladas por abortos fortuitos, o al menos tratar de entender la magnitud de estos casos, Luciana tenía que pedir datos sobre otros delitos. Esto es algo que le explicó Verónica, la abogada que mencionamos antes.

Luciana: Porque yo le decía bueno, estoy pidiendo los delitos de aborto. Ella me decía “pide los relacionados” y yo, ¿relacionados con qué? O sea, ¿cómo relacionados? Y ella usó ese término, de delitos relacionados, para pensar en todos estos otros tipos penales que las autoridades han usado para criminalizar a las mujeres hablando de abortos, pero nombrándolo de otras formas. Y esos son: homicidio doloso, homicidio en razón de parentesco, infanticidio, filicidio, incluso omisión de cuidados en algunos casos. Y por supuesto el tema es este, la diferencia brutal que hay en cuanto a la pena y además que las vuelve completamente invisibles. Porque yo lo que decía era bueno, ¿cómo pedimos un delito que no existe? ¿no? Porque están sentenciadas, están encarceladas como homicidas, como si fueran asesinas, como si hubieran, no sé, asesinado a una persona en la esquina de la casa con un arma. Y en realidad lo que ocurrió fue algo muy distinto. Pero como tú sabes, a la hora de las estadísticas, pues uno pide delitos, las cosas que son cuantificables. Entonces ese es el otro tema. No sabemos cuántas mujeres hay en esta situación. Esa es la verdad. Las Libres ha hecho un trabajo brutal, la verdad, de rastreo y de mapeo de esta situación. Habían llegado al número de 200. Yo hice otro trabajo, también insistente al menos. Había llegado al número 28. En fin. Lo cierto es que no sabemos porque está mal tipificado. Entonces no podemos decirle a las autoridades “oye, dame todas las personas que estén bajo este delito, pero que en realidad su crimen haya sido otro”. Es un embrollo legal que en realidad la verdadera consecuencia es que desconocemos completamente el tema y que no tenemos manera de saberlo a menos que recorramos todas las cárceles y le preguntemos a las mujeres, “oye, ¿cómo llegaste acá? ¿No? ¿Cuál es tu historia, pues?”

Eliezer: Después de la pausa, las historias que encontró Luciana. Ya volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Silvia: Me gustaría hablar ahora de justamente de esas historias ¿no? que tú encontraste. Pero primero, te quería preguntar en términos más generales, qué características en común encontraste que tienen las mujeres que están o que estuvieron en esta situación.

Luciana: Sí. Hay muchas características comunes y eso también fue revelador, ¿no? En la investigación. Digamos, lo primero es que estaban en situaciones vulnerables de alguna u otra manera. Digo, yo sé que no es el hilo negro, no, pero las violencias están completamente conectadas. O sea, yo encontraba este tipo de violencia del Estado, pero normalmente aparecía violencia física, violencia sexual, violencia intrafamiliar, es decir, era impresionante cómo se iban concatenando las violencias. Eso me impresionó. Mujeres que estaban en situaciones de vulnerabilidad de algún tipo, lo cual no siempre implica una situación de vulnerabilidad económica o socioeconómica, que es algo que también me sorprendió. O sea, sí hay casos de mujeres indígenas en la Sierra de Guerrero, pero también hay casos de mujeres de clase media en Querétaro, con un trabajo estable. Pero sí había una situación de vulnerabilidad de algún tipo. Después, la falta de debido proceso es otra de las características comunes, por supuesto. Violencia por parte de abogados, de abogadas, de jueces, de juezas, de todo el sistema en sí mismo. Cuando uno va revisando la carpeta de investigación, como poquito a poquito, se va encontrando con muchísimas deudas que tiene el sistema de injusticia penal de nuestro país con las mujeres, ¿no? No era solo que se abría la carpeta de investigación. Todo lo que ocurría después estaba mal: no se tomaban en cuenta sus declaraciones, no se les preguntaba a ellas qué había ocurrido, no se presentaban pruebas, se daban sentencias sin de verdad ninguna prueba.

Eliezer: Algo que encontró Luciana que se repite en estos casos es que la Fiscalía usa una prueba pseudocientífica, que se llama docimasia pulmonar. Lo que hacen, básicamente, es poner los pulmones del producto en un lugar con agua. Si flotan, las autoridades toman eso como prueba de que respiró al nacer. O sea, que no nació muerto. Y eso es una de las dos cosas que tienen que probar en estos casos de homicidio: que no nació muerto y que hubo intención.

Luciana: Es una prueba con un margen de error brutal y sin embargo era una de las pruebas como estrella de la Fiscalía. Y era donde decía no, no el producto respiró porque los pulmones flotaron y no hay indicios de ninguna infección. Entonces ese tipo de cosas a mí me llamaba mucho la atención.

Y claro, todas las historias empezaban normalmente en baños ¿no? Eran, o sea, justamente eran fortuitos y entonces ocurrían en lugares extrahospitalarios. Normalmente eran baños porque uno se siente mal y lo primero que hace es, pues ir al baño. Entonces ocurrían en las letrinas de las casas, en los baños. Y las detenciones se daban en muchas ocasiones adentro de los hospitales. Cuando estas mujeres eran atendidas, se las llevaba al hospital o a la clínica, y en ese lugar llegaban las autoridades y hacían directamente la aprehensión. En muchos casos se la llevaban directamente, en otras pasaban algunos días. Pero esa era otra de las características comunes, porque en esos lugares venían las denuncias y eso también era muy particular y, digamos, era común que el personal de la salud hiciera la denuncia. Y ahí pues es muy raro porque yo en algún momento, claro, da enojo ver este tipo de cosas. Pero lo que encontré también hablando con el personal de la salud es que tenían mucho miedo. O sea, hay mucho desconocimiento, hay mucha falta de información y entonces tenían miedo de estar ellos mismos, ellas mismas, cometiendo un delito, siendo cómplices de algún tipo de delito. Y entonces normalmente las denuncias se daban en ese contexto, ¿no? En un contexto de desinformación absoluta. Creo que esas son, un poco, las características comunes que había dentro de estos casos.

Silvia: ¿Y qué te contaron sobre las condiciones dentro de las cárceles?

Luciana: Bueno, ese es otro de los grandes temas, ¿no? Y uno se iba anclando con el otro. Claro. Los periodos de reclusión de estas mujeres pues también eran muy rudos. Primero porque normalmente me contaban que llegaban a estos lugares y las demás ya sabían lo que había ocurrido. Ya sabían, digamos, la versión fatídica de lo que había ocurrido de mataste a tu hijo, ¿no? Y entonces eso implicaba de por sí un una situación de mucha desamparo dentro de las prisiones y que les costaba al principio, como generar relaciones porque justo, ya se había corrido el rumor de lo que había ocurrido, de la versión que las autoridades habían querido correr.

Eliezer: Y claro, las cárceles de México, y en general en América Latina, no están pensadas para mujeres. El sistema penitenciario no tiene en cuenta sus necesidades.

Luciana: Me encontré con algunas cárceles que estaban hechas, digamos, en, no sé, en azoteas de las cárceles varoniles. Con una sobrepoblación brutal. Las mujeres recibimos castigos más terribles por cometer los mismos delitos que los hombres. Las mujeres somos más abandonadas adentro de las prisiones que los hombres. Y eso está como muy medido. La forma en la cual las familias abandonan mucho más rápido a una mujer que a un hombre cuando está en prisión. Y esto es fundamental porque las redes, a la hora de estar en una situación carcelaria, las redes de apoyo se vuelven fundamentales. De hecho, las mujeres que fueron tan generosas de compartirme su historia para este libro tienen redes muy fuertes y creo que esa es una de las grandes cualidades por las cuales primero obtuvieron en algún momento algo cercano a la justicia, es decir, fueron excarceladas, y tuvieron la valentía de contar su historia y de llevarlo a medios de comunicación y de tener un acompañamiento de una, de una colectiva, de una organización. Justo por estas redes tan fuertes. Porque la verdad es que la realidad del encarcelamiento de mujeres es muy distinto. Entonces sí, la verdad es que la historia dentro de la prisión y sobre todo hay muchas que son madres, que se vieron obligadas a estar separadas de sus hijos e hijas, durante todo ese periodo, es realmente brutal. Y me acuerdo una de ellas que me decía como, “yo tengo una hija, o sea, el juez me estaba diciendo que yo era mala madre por no haberme enterado que estaba embarazada y por no haber podido reaccionar bien ante una emergencia obstétrica. Y entonces decidió separarme tres años de mi hija, ¿no? A la que yo tengo que cuidar”. O sea, de ese estilo son este tipo de absurdos jurídicos.

Silvia: Hablemos de un caso. En tu libro tocas cinco. Pero hablemos del caso de Aurelia. Esta mujer de Guerrero que ella sufre un crimen, es víctima de violencia sexual. Cuéntanos sobre su caso.

Luciana: Sí. Aurelia es una mujer indígena que vive en la Sierra de Guerrero. Venía siendo víctima de violencia sexual y de un cúmulo de violencias, ¿no? Ahí es donde decimos, evidentemente la violencia sexual siempre va acompañada, o no siempre, pero en muchas ocasiones de violencia económica, violencia psicológica. Y es justo el caso de Aurelia, que vive además en una comunidad que se rige bajo usos y costumbres. Y esto le da, digamos, un tinte muy específico a su caso.

Lo que ocurre es que ella es violada por un policía de esa comunidad. A raíz de estas violaciones ella queda embarazada y lo que siente es profundo miedo, porque en esa comunidad, las mujeres que quedan embarazadas sin tener una pareja son violentadas por la comunidad entera. Es jovencita. Esto ocurrió en 2019. Ella decide salirse e irse con una tía hasta Iguala. Ella le pide ayuda a una tía, se va a la casa de su tía, y en ese ínterin, tiene algún tipo de sangrado y ella piensa que ya, que le bajó la regla y que todo estaba bien y que ya no había embarazo. Entonces continúa su vida hasta que una tarde, estando sola en la casa de su tía, tiene una emergencia obstétrica, un parto fortuito. Y ella agarra un cuchillo para cortar el cordón umbilical. Ahí, evidentemente tiene mucha pérdida de sangre. Cuando la encuentra la tía horas después está realmente al borde de la muerte. Tiene una pérdida de sangre brutal. Termina en el hospital, es llevada a los servicios de emergencia, y ahí se da una vez más la denuncia, de parte del personal de la salud. Cuando llegan las autoridades, llegan ahí mismo al hospital. Ella en ese momento no hablaba español, ella hablaba náhuatl y pues, llegan las autoridades la acusan en español. Ella no entiende absolutamente nada, está en una situación además de crisis de salud absoluta. Y en ese momento inicia, digamos, el proceso de criminalización contra Aurelia.

Eliezer: Luciana se enteró sobre la historia de Aurelia en 2021. Aurelia ya estaba encarcelada. Y en ese momento, su defensa legal no quería llevar el caso a los medios. Habían acordado lo que en México se llama “juicio o procedimiento abreviado”. Es aceptar la culpabilidad para obtener una condena menor. Así que la pena de Aurelia era de 13 años, en vez de 25, que es lo que podría haber sido.

Silvia: Un tiempo después, abogadas del Instituto Mexicano de Derechos Humanos y Democráticos lograron que la justicia le permitiera a Aurelia defenderse en un juicio oral, porque en el primer juicio habían violado sus derechos. Esto implicaba un riesgo, dice Luciana, porque podrían darle una pena más larga de la que tenía. Entonces, para este segundo proceso, la defensa legal sí quería tener la atención de los medios.

Luciana: Se necesitaba un poco de presión, ¿no? Para que las autoridades finalmente actúen como deberían. Y es un caso en el que pasan unas cosas de verdad que son surrealistas y brutales. La primera es que la Comisión de Atención a Víctimas es parte de quien la acusa. O sea, la CEAV, está sentada, digamos, de parte de la Fiscalía, porque dicen que están representando al bebé, al producto. Lo otro que pasa, muy terrible, es que durante las audiencias están los padres de Aurelia, que también, con muy poquito conocimiento del español –Aurelia dentro de prisión, empieza a aprender español, eso es muy interesante, para ese momento ya hablaba español muy bien–. Los padres no tenían mucho conocimiento del español y están obviamente presentes en el juicio y la Fiscalía los está utilizando a su favor. Los estaba poniendo de víctimas indirectas por ser los “abuelos”, y estoy haciendo comillas, los abuelos del producto de la víctima y ellos no sabían. Ellos venían declarando, pensando que estaban ayudando a salir de la cárcel a su hija. Entonces en alguna de las audiencias dicen las abogadas defensoras: “Oigan, ¿ustedes les han preguntado a ellos si saben lo que está ocurriendo?” Y cuando la jueza pregunta pues se da cuenta que no.

Otra cosa terrible que ocurre en ese caso es que en algún momento piden el cambio de la medida cautelar. Dicen bueno, a ver si está. Si estamos llevando este juicio, ella puede estar en en libertad mientras se lleva el juicio. Y la jueza se lo niega porque dice que es una mujer pobre que quizás no tenga los medios económicos para llegar a las audiencias. De ese nivel es lo surrealista del caso. Bueno, finalmente, yo acompaño todo este proceso y me toca como un poco en tiempo real, ¿no? Mientras yo estaba escribiendo el libro, estaba acompañando el proceso. Lo que ocurre finalmente, al terminar este segundo juicio, es que ella es absuelta. Finalmente a ella la absuelven. Pero la verdad es que se da en un contexto de muchísima presión mediática, muchísima, de muchísimas… Cuando empieza, la jueza en esa última audiencia, a hablar, la verdad que todas pensaron que no iba a salir libre, ¿no? Todas pensaron que que la sentencia iba a ser condenatoria, porque ella empieza a hablar y dice que las pruebas ahí están y que demás y solo se ha agarrado de una pequeña cosita para absolver la situación. Lo que dice la jueza es como, Aurelia estaba sola en ese momento, no se puede comprobar qué fue lo que pasó. Y entonces, por eso, duda razonable. La vamos a absolver. Pero toda la argumentación jurídica va en contra. Y eso nos contaban las abogadas, es muy brutal, ¿no? Porque finalmente impide que haya una como un precedente claro sobre otros casos del mismo tipo.

Silvia: Aurelia quedó libre en diciembre de 2022.

Eliezer: Vamos a hacer una última pausa y a la vuelta hablamos con Luciana sobre la situación de las mujeres que siguen encarceladas por abortos fortuitos. Ya volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta.

Silvia: ¿Qué está pasando con los casos de las mujeres que siguen encarceladas? ¿Pueden usar como argumento esta decisión de la Suprema Corte de que ahora está despenalizado el aborto? ¿O en realidad no, porque están encarceladas por homicidio?

Luciana: Pues sí, técnicamente no, digamos. Yo sí creo que finalmente todo el marco legal que tenemos ahora, que no teníamos hace cinco o 10 o 15 años, evidentemente mejora la situación para que las mujeres puedan enfrentarse a la justicia. Jurídicamente y directamente no, no pueden decir bueno, desde el 2021 la Suprema Corte de Justicia dijo que es inconstitucional la prohibición absoluta del aborto, porque en realidad… Justo ¿no? Están sentenciadas por otros delitos. Claro que ese contexto les permite a las mujeres tener muchas más herramientas de defensa, en las organizaciones, en el acompañamiento, incluso en la opinión pública, que no es para nada menor. Pero no es que haya una relación completamente directa, y de hecho hablaba con una activista que se llama Ninde MolRe, que está acompañando un caso en Yucatán, que es de verdad algo que yo no vi en todo este tiempo y que es una locura y es interesante. Es una madre y su hija. Rocío es la mamá, tiene una hija de 13 años, la hija queda embarazada, pide apoyo para que la ayuden a abortar y ella dice, y esto me parece como muy importante, ella dice “yo había leído que el aborto ya era legal, entonces yo pues la ayudé a abortar a mi hija porque yo ya había leído que ya no se podía criminalizar el aborto”. Y entonces la ayuda. Ella a los dos días se siente mal. Entonces la abuela la lleva a un centro médico y cuando llegan a este centro médico le hacen preguntas, de más, se enteran de lo que ocurrió. Ella queda en tutoría del Estado, la niña, y a la mamá le abren una carpeta por intento de feminicidio. Entonces, digamos, todas estas cosas siguen ocurriendo. Hay un mejor entorno, hay un mejor marco jurídico, hay un mejor, hay un entorno mucho menos punitivo. Sí, lo hay. Faltaría, y para mí eso es muy importante, la legalización del aborto en todas las entidades federativas, porque finalmente el aborto es algo que se aborda desde lo local. Entonces, tanto la inconstitucionalidad de la prohibición absoluta como lo que vino después, que fue como la legalización federal del Código Penal Federal, son muy importantes, pero digamos, lo necesario es que todos los códigos penales locales de las entidades federativas homologuen su Código Penal y lo saquen. Saquen al aborto del Código Penal, ¿no? O sea, básicamente eso es lo que debería venir en términos legales. Ahora bien, estos otros casos lamentablemente siguen ocurriendo y hemos tenido un par de ejemplos incluso en el último tiempo.

Eliezer: Un caso reciente que recibió mucha cobertura en los medios es el de Esmeralda, una niña del estado de Querétaro, de 14 años. Un familiar la violó y ella puso una denuncia. Pero la investigación se cerró porque según la justicia no había suficientes pruebas para castigar al violador.

Luciana: Y además dicen que ella, una niña de 14 años, había incurrido en algunas contradicciones a la hora de dar su testimonio. Por esta violencia sexual ella queda embarazada y lo que ocurre es que tiene una emergencia obstétrica. Tiene un tema de salud, tiene un parto fortuito, el embarazo se pierde, el producto se pierde. Y otra vez abren una carpeta por homicidio. En su caso fue homicidio doloso. Y además estaban pidiendo 500.000 pesos de reparación del daño para el violador porque era el progenitor, digamos, del producto en gestación. Y eso es algo que ocurre en muchas ocasiones. Además de la pena de cárcel. Se pide una reparación del daño para el hombre progenitor del producto ¿no? Y si hay algo que está ausente en todas estas historias, la verdad, son los progenitores, no aparecen en ningún momento. O aparecen solo para decir no, quién sabe si sea mío, adiós. No volvimos a hablar. Esto aparece en las carpetas de investigación.

Por suerte este caso se hace mediático. Y lo toman las organizaciones y llega a oídos de de la nueva Secretaría de las Mujeres, de Citlalli Hernández, porque además sabemos que Querétaro es un Estado particularmente conservador, en ese sentido. Entonces, bueno, a través del diálogo, Citlalli Hernández consigue que se cierre la carpeta de investigación. Yo en ese momento hablé con las abogadas de Adax Digitales, que era quien estaba acompañando el caso, y después hablé con la secretaria, con Citlalli Hernández y bueno, yo le preguntaba qué pasa con este otro caso, ¿no? ¿Qué pasa con el caso de violación? Y ella me dijo que bueno, tenían que esperar a los tiempos de la víctima si la víctima quería volver a iniciar el proceso legal, porque sabemos que eso pues requiere de un desgaste emocional muy, muy terrible, ¿no? Entonces. Bueno, en este caso, digamos, se resuelve, por decirlo de alguna manera, pero solamente por la mediatización que tuvo, porque la secretaria lo tomó de forma individual, porque no lo sacaron por una cuestión jurídica, no hubo una resolución jurídica. Una resolución política, bienvenida sea pues. Pero digamos, esto puede seguir ocurriendo una y otra vez.

Silvia: Luciana trabaja en noticieros, cubriendo noticias diarias, así que le llegan casos con titulares tipo: “Madre asesina a su bebé recién nacido en Tijuana y lo guarda en el refrigerador”.

Luciana: Y entonces, cuando empiezo a leer, todo parece indicar que fue una emergencia obstétrica en una bañera, que ella no sabía que estaba embarazada. Que pues agarra un cuchillo para cortar el cordón umbilical que obviamente está en un estado absoluto de shock. Imagínate si una no sabe que está embarazada, tiene una emergencia obstétrica mientras te estás bañando y no sabe qué hacer con el producto y entonces lo guarda, digamos. Y ella se va a entregar además, a las autoridades. Eso es lo que ocurre. Ella va a entregarse. La mujer ya fue vinculada a proceso. Pero son esos casos –claro, yo no tengo más contexto que ese– Pero son esos casos donde yo siempre digo oigan, espérense, madre asesina, espérense. Hay que ver qué está pasando con esa mujer. ¿Cuál es su contexto? ¿Cómo llegó hasta ahí? ¿Qué está ocurriendo? ¿Nació vivo o no nació vivo? ¿Cómo puedes asegurar que nació vivo? En fin, digamos. La verdad es que siguen ocurriendo estos casos.

Silvia: Y ahora México tiene una presidenta. Es de izquierda. En el caso de Esmeralda, ella dijo: no se debería criminalizar a una niña de 14 años. Ella dijo que no estaba de acuerdo con la Fiscalía. ¿Pero es suficiente? O sea, ¿qué necesita pasar en México para que no se repitan casos como el de Esmeralda y los de tu investigación?

Luciana: Pues tendría que cambiar el mundo, Silvia. No, no sé, digamos. Creo que no hay una respuesta definitiva. Creo que son pequeños pasos que uno va haciendo. Yo diría lo primero es conquistar la despenalización del aborto en las 32 entidades federativas. Eso creo que es muy importante. A partir de ahí, todo el trabajo que se debería hacer en materia de educación. Justamente para combatir eso que hablábamos hace un rato: el miedo del personal de la salud a estar cometiendo un delito si no se informa de un posible aborto. Y hay otra contraparte que tiene que ver también con el fortalecimiento o el cambio en el sistema de justicia penal. Lo cierto es que en México no solo tenemos un problema de esta naturaleza, sino un problema de impunidad, sino un problema de desigualdades. Sí tendría que cambiar todo el entramado para podernos asegurar de que ya no existan estos casos.

Después tendría que venir todo un cambio cultural. Porque además, digamos, todo esto ocurre porque hay personas que pertenecen a ese sistema de justicia que creen realmente en lo que están diciendo. Los policías que llegan a atender el delito, la denuncia. Ellos creen realmente que hay una mujer que es asesina, y que entonces hay que actuar en su contra. Y leyendo además las cosas brutales que se dicen en esos lugares… Me acuerdo del cierre de una de las audiencias donde la Fiscalía empieza su alegato diciendo, “Mamá, no me mates. Eso podría haber dicho el bebé a la hora de…” Entonces, digamos, todas esas personas realmente creen en lo que están diciendo. No es solo una saña en contra de las mujeres. Hay una creencia profunda de que esas mujeres cometieron un delito. Y cometieron un delito contra una persona indefensa, además. Y toda esta idea romantizada de la maternidad y demás. Pero ese cambio cultural es fundamental para que las personas que participan en los procesos no vean la situación desde esa óptica tan retorcida y surrealista. Lo mismo el personal de la salud, lo mismo el personal que llega a atender la emergencia. Es decir, es toda una cadena donde solo se llega hasta las últimas instancias adentro de una prisión, cuando cada eslabón falla, por decirlo de alguna manera, ¿no?

Yo creo que cuanto más lo hablemos y más lo socialicemos, más vamos a afinar esa mirada de la que te comentaba, ¿no? Y creo que todos podremos estar mucho más pilas a tratar de diferenciar de cuando estamos hablando, no sé, de una madre que se levantó y asesinó a su hijo de cinco años, a una mujer que tuvo una emergencia obstétrica y el producto se perdió en ese proceso, ¿no? Pero digamos, yo creería que es una solución mucho más estructural y de muchas variables.

Silvia: Bueno, Luciana, muchas gracias.

Luciana: Gracias a ti, Silvia. Qué gusto.

Silvia: Este episodio fue producido por mí. Lo editó Eliezer. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido y la música es de Elías González.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Soy Silvia Viñas. Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Eliezer: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia Viñas: And I’m Silvia Viñas. In Mexico, there are women who face penalties similar to those of criminals for having abortions. Some, after having involuntary abortions.

Eliezer: This, in a country that a few years ago established an important precedent in Latin America for reproductive rights. Let’s remember that the Supreme Court of Justice decriminalized abortion at the federal level in 2021 and in 2023 declared its prohibition unconstitutional. In other words: it declared criminalizing the termination of a pregnancy unconstitutional.

Silvia: But that didn’t mean that abortion would automatically be legal throughout the country. The situation varies greatly from state to state. More than 20 have decriminalized it in their constitutions, but a dozen still classify it as a crime. Today, despite the decriminalization of abortion at the federal level, in some places in Mexico local authorities use different criminal categories to criminalize, persecute and imprison women who have involuntary abortions or obstetric emergencies.

It’s September 12th, 2025.

Silvia: Luciana, a few years ago, with the Supreme Court’s decision, Mexico became something like an example, let’s say, in the region, right? And you started your research on the criminalization of abortion before that. But you published it later, in 2024. I’d like to start with a question that’s quite general, but. Why do you think it’s important to highlight these cases of abortion criminalization in today’s Mexico?

Luciana Wainer: Well, exactly what usually happens, let’s say, in Mexico but everywhere, is that ultimately the legal framework is just the beginning. It’s just the first thing that transforms and that doesn’t necessarily make an automatic, complete, or rapid transformation in people’s lives, in the lives of women and pregnant people, in this particular case.

Eliezer: Luciana Wainer is an Argentine journalist who has been in Mexico for more than a decade. We spoke with her because last year she published a book called Fortuito: el otro lado de la criminalización del aborto en México [Fortuitous: the other side of abortion criminalization in Mexico].

Luciana: Legal changes are just one part. They’re just a start to making a real transformation. Cultural change, cultural decriminalization, that takes much, much longer, and I think until that happens, cases of criminalization or stigmatization or persecution will continue happening in our country.

Silvia: Luciana began investigating the criminalization of abortion from an academic sphere, while doing a master’s degree.

Luciana: When I started the research, my objective was to talk about the criminalization of abortion per se. That is, perhaps to have a much more accurate number of the people, of the women who were imprisoned for the crime of abortion. How the situation was in the country. What happened to me was that I began to realize that when I started investigating the crime of abortion in particular, I found almost nothing. I would send information requests and then the states would respond to me, well, that there were no imprisoned women, that there were very few, that there were men, for example, because they were health personnel, who had assisted abortions. But I couldn’t find it… There was something like that didn’t add up for me in that sense, because I knew that criminalization was there.

Eliezer: One of Luciana’s sources during this research was Verónica Cruz. She’s an activist, lawyer, human rights defender, and director of Las Libres, an organization that promotes and defends women’s rights from the state of Guanajuato.

Luciana: She’s the first one who tells me hey, “well look, for abortion, not so much. But I do have cases of homicide by reason of kinship.” And then that was the first time I heard that and I didn’t understand the relationship there was. I said. But how? And she tells me, “well, yes, it’s that many women with obstetric emergencies, with premature births, with fortuitous abortions, end up imprisoned, but not for the crime of abortion, but for the crime of homicide, homicide by reason of kinship.” And then, when I hear that, it seems to me, honestly, so scandalous, that I think it was an isolated case, right? That it was a case she had accompanied, one of these things that sometimes happen. And I start pulling that thread, that information. And talking with colleagues, suddenly a journalist colleague tells me, “I covered a case some years ago,” etc., etc. And talking with another and another organization… And then I start sending information requests and I realize, let’s say, that it’s not a generalized situation, but it is a systematic criminalization of abortion, doing it through this criminal type. And of course, that brings, of course, many, many complications when it comes to tracking cases, counting them, mapping them in the country. And for women, without a doubt. First of all, for them the difference between being pointed out or sentenced for abortion to being pointed out or sentenced for homicide is an abysmal difference.

Silvia: Yes, I want to break down several things you’ve mentioned. First this word, “fortuitous,” right? You hear “obstetric emergency”… Explain to us a bit so it’s clear what a fortuitous abortion is.

Luciana: That word when I was choosing the book’s title was a big discussion with the editors and others, because it was interesting. Notice that actually the concept of fortuitous birth from journalism we had… Well, we didn’t use it at all. And it starts being used because of one of these cases. It starts being used because of the case of Dafne McPherson

Archive audio, journalist: She had a fortuitous birth without even knowing she was pregnant.

Luciana: Who has a fortuitous birth in the bathroom of a shopping center. She is criminalized, she is persecuted.

Archive audio, journalist 1: The young woman was accused of aggravated homicide against her newborn daughter, and was sentenced to 16 years in prison.

Archive audio, journalist 2: We spoke with her and she told us what happened.

Archive audio, Dafne: They took my life away from me. They took away the opportunity to be with my daughter, to be with my family.

Luciana: And she spends three years in a prison in Querétaro. And we learned that concept there and that seemed very, very important to me. The use of language, actually in all these cases is very important and it happens even in the searches we do on the Internet. The first thing we do, we go in to see how many cases there are or where. And I found that, of course, the media had done the coverage naming these cases completely erroneously, from calling the product a baby, mother to the woman who was having an obstetric emergency.

Eliezer: There’s an emotional charge behind “baby” and “mother.” And they’re not precise words to use in these cases. Saying “product,” like “product of gestation,” removes that charge. It’s a medical, scientific term.

Luciana: And there were exactly these, let’s say, confusions between abortion, fortuitous abortion, fortuitous birth, obstetric emergency. Let’s see, the term fortuitous implies that, let’s say, it’s not sought, it’s not intentional, it’s random. And in that sense a fortuitous birth has to do with having a birth in a place, that is, first, that wasn’t expected. And it’s a place outside the hospital that isn’t prepared for that, with all the implications that has. And what normally happens to these women is that the State fails twice very quickly. The first is not attending to the health emergency, which is an obligation the State has and after that it criminalizes the women. It takes it from the criminal side. So fortuitous, it seemed to me like it encompassed, right? A bit the soul and where, where all this situation was born from.

Silvia: So then, let’s see, you found that women weren’t being imprisoned for the crime of abortion, but for homicide, as if they were murderers. Right? How does that happen?

Luciana: Yes, exactly. Because also. Of course, by that time and now much more, the crime of abortion doesn’t reach prison in our country. There was only one entity when I started the research that still reached prison as a result of the changes there were in the judicial system. But of course, the first difference between abortion and homicide is the number of years in prison. In the case of abortion, even if they find you guilty, you don’t reach prison, you don’t step foot in prison. And in the crime of homicide we’re talking about 10, 20, 30 up to 50 years, well. So that’s the most brutal difference.

Eliezer: This means that to be able to arrive at a figure of women imprisoned for fortuitous abortions, or at least try to understand the magnitude of these cases, Luciana had to ask for data on other crimes. This is something that Verónica, the lawyer we mentioned before, explained to her.

Luciana: Because I would tell her well, I’m asking for abortion crimes. She would tell me “ask for the related ones” and I, related to what? I mean, how related? And she used that term, related crimes, to think about all these other criminal types that authorities have used to criminalize women talking about abortions, but naming it in other ways. And those are: intentional homicide, homicide by reason of kinship, infanticide, filicide, even omission of care in some cases. And of course the issue is this, the brutal difference there is in terms of the penalty and also that makes them completely invisible. Because what I was saying was well, how do we ask for a crime that doesn’t exist? right? Because they’re sentenced, they’re imprisoned as murderers, as if they were assassins, as if they had, I don’t know, murdered a person on the corner of the house with a weapon. And actually what happened was something very different. But as you know, when it comes to statistics, well one asks for crimes, things that are quantifiable. So that’s the other issue. We don’t know how many women are in this situation. That’s the truth. Las Libres has done brutal work, truly, of tracking and mapping this situation. They had reached the number of 200. I did other work, also insistent at least. I had reached the number 28. Anyway, What’s certain is that we don’t know because it’s badly classified. So we can’t tell the authorities “hey, give me all the people who are under this crime, but whose crime was actually another.” It’s a legal mess that actually the real consequence is that we completely don’t know the issue and that we have no way of knowing unless we go through all the prisons and ask the women, “hey, how did you get here? Right? What’s your story, well?”

Eliezer: After the break, the stories that Luciana found. We’ll be right back.

Eliezer: We’re back on El hilo.

Silvia: I’d like to talk now about exactly those stories, right? that you found. But first, I wanted to ask you in more general terms, what common characteristics you found that the women who are or were in this situation have.

Luciana: Yes. There are many common characteristics and that was also revealing, right? In the research. Let’s say, the first thing is that they were in vulnerable situations in one way or another. I mean, I know it’s not groundbreaking, no, but the violence is completely connected. That is, I found this type of violence from the State, but normally physical violence, sexual violence, intrafamilial violence appeared, that is, it was impressive how the violences were concatenating. That impressed me. Women who were in situations of vulnerability of some type, which doesn’t always imply a situation of economic or socioeconomic vulnerability, which is something that also surprised me. I mean, yes there are cases of indigenous women in the Sierra of Guerrero, but there are also cases of middle-class women in Querétaro, with a stable job. But yes there was a situation of vulnerability of some type. Then, the lack of due process is another of the common characteristics, of course. Violence by lawyers, by judges, by the entire system itself. When one goes reviewing the investigation file, like little by little, one finds many, many debts that our country’s criminal injustice system has with women, right? It wasn’t just that the investigation file was opened. Everything that happened after was wrong: their statements weren’t taken into account, they weren’t asked what had happened, evidence wasn’t presented, sentences were given without really any evidence.

Eliezer: Something that Luciana found that repeats in these cases is that the Prosecutor’s Office uses a pseudoscientific test, called pulmonary docimasia. What they basically do is put the product’s lungs in a place with water. If they float, the authorities take that as proof that it breathed when born. That is, that it wasn’t born dead. And that’s one of the two things they have to prove in these homicide cases: that it wasn’t born dead and that there was intention.

Luciana: It’s a test with a brutal margin of error and yet it was one of the Prosecutor’s Office’s star pieces of evidence. And it was where they said no, no the product breathed because the lungs floated and there were no signs of any infection. So that type of thing really caught my attention.

And of course, all the stories normally started in bathrooms, right? They were, that is, exactly they were fortuitous and so they happened in extra-hospital places. Normally they were bathrooms because one feels bad and the first thing one does is, well go to the bathroom. So they happened in house latrines, in bathrooms. And the arrests happened on many occasions inside hospitals. When these women were attended to, they were taken to the hospital or clinic, and in that place the authorities arrived and made the arrest directly. In many cases they took them directly, in others some days passed. But that was another of the common characteristics, because in those places the complaints came and that was also very particular and, let’s say, it was common for health personnel to make the complaint. And there well it’s very strange because at some point, of course, it makes you angry to see this type of thing. But what I also found talking with health personnel is that they were very afraid. I mean, there’s a lot of ignorance, there’s a lot of lack of information and so they were afraid of themselves, themselves, committing a crime, being accomplices to some type of crime. And so normally the complaints happened in that context, right? In a context of absolute misinformation. I think those are, a bit, the common characteristics there were within these cases.

Silvia: And what did they tell you about the conditions inside the prisons?

Luciana: Well, that’s another of the big issues, right? And one was anchoring with the other. Of course. The periods of confinement of these women were also very rough. First because normally they told me that they arrived at these places and the others already knew what had happened. They already knew, let’s say, the fateful version of what had happened that you killed your child, right? And so that implied in itself a situation of great helplessness within the prisons and that it was hard for them at first, like generating relationships because exactly, the rumor had already spread of what had happened, of the version that the authorities had wanted to spread.

Eliezer: And of course, Mexico’s prisons, and generally in Latin America, aren’t designed for women. The penitentiary system doesn’t take their needs into account.

Luciana: I found some prisons that were made, let’s say, in, I don’t know, on rooftops of male prisons. With brutal overpopulation. Women receive more terrible punishments for committing the same crimes as men. Women are more abandoned inside prisons than men. And that’s well measured. The way in which families abandon a woman much faster than a man when in prison. And this is fundamental because networks, when it comes to being in a prison situation, support networks become fundamental. In fact, the women who were so generous to share their story for this book have very strong networks and I think that’s one of the great qualities for which first they obtained at some point something close to justice, that is, they were released from prison, and they had the courage to tell their story and take it to the media and to have accompaniment from a collective, from an organization. Exactly because of these very strong networks. Because the truth is that the reality of women’s imprisonment is very different. So yes, the truth is that the story inside prison and especially there are many who are mothers, who were forced to be separated from their sons and daughters, during all that period, is really brutal. And I remember one of them who told me, “I have a daughter, I mean, the judge was telling me that I was a bad mother for not having realized I was pregnant and for not having been able to react well to an obstetric emergency. And so he decided to separate me three years from my daughter, right? Who do I have to take care of?” I mean, that style is these types of legal absurdities.

Silvia: Let’s talk about a case. In your book you touch on five. But let’s talk about the case of Aurelia. This woman from Guerrero who suffers a crime, is a victim of sexual violence. Tell us about her case.

Luciana: Yes. Aurelia is an indigenous woman who lives in the Sierra of Guerrero. She had been a victim of sexual violence and an accumulation of violences, right? That’s where we say, evidently sexual violence always goes accompanied, or not always, but on many occasions by economic violence, psychological violence. And it’s exactly Aurelia’s case, who also lives in a community that is governed under uses and customs. And this gives, let’s say, a very specific tinge to her case.

What happens is that she is raped by a policeman from that community. As a result of these rapes she becomes pregnant and what she feels is profound fear, because in that community, women who become pregnant without having a partner are violated by the entire community. She’s young. This happened in 2019. She decides to leave and go with an aunt to Iguala. She asks an aunt for help, goes to her aunt’s house, and in that interim, she has some type of bleeding and she thinks that’s it, that her period came and that everything was fine and that there was no longer a pregnancy. So she continues her life until one afternoon, being alone at her aunt’s house, she has an obstetric emergency, a fortuitous birth. And she grabs a knife to cut the umbilical cord. There, evidently she has a lot of blood loss. When the aunt finds her hours later she’s really on the verge of death. She has a brutal blood loss. She ends up in the hospital, is taken to emergency services, and there the complaint is made once again, by health personnel. When the authorities arrive, they arrive right there at the hospital. She at that moment didn’t speak Spanish, she spoke Nahuatl and well, the authorities arrived and accused her in Spanish. She understands absolutely nothing, she’s also in a situation of absolute health crisis. And at that moment begins, let’s say, the criminalization process against Aurelia.

Eliezer: Luciana found out about Aurelia’s story in 2021. Aurelia was already imprisoned. And at that moment, her legal defense didn’t want to take the case to the media. They had agreed to what in Mexico is called an “abbreviated trial or procedure.” It’s accepting guilt to obtain a lesser sentence. So Aurelia’s sentence was 13 years, instead of 25, which is what it could have been.

Silvia: Some time later, lawyers from the Mexican Institute of Human Rights and Democrats managed to get justice to allow Aurelia to defend herself in an oral trial, because in the first trial they had violated her rights. This implied a risk, says Luciana, because they could give her a longer sentence than she had. So, for this second process, the legal defense did want to have media attention.

Luciana: A bit of pressure was needed, right? For the authorities to finally act as they should. And it’s a case in which some things happen that are truly surreal and brutal. The first is that the Victims’ Attention Commission is part of who accuses her. I mean, the CEAV, is sitting, let’s say, on the Prosecutor’s Office’s side, because they say they’re representing the baby, the product. The other thing that happens, very terrible, is that during the hearings Aurelia’s parents are there, who also, with very little knowledge of Spanish –Aurelia inside prison, starts learning Spanish. That’s very interesting, by that time she already spoke Spanish very well–. The parents didn’t have much knowledge of Spanish and are obviously present at the trial and the Prosecutor’s Office is using them in their favor. They were putting them as indirect victims for being the “grandparents,” and I’m making quotation marks, the grandparents of the victim’s product and they didn’t know. They came declaring, thinking they were helping to get their daughter out of jail. So in one of the hearings the defense lawyers say: “Hey, have you asked them if they know what’s happening?” And when the judge asks well she realizes that no.

Another terrible thing that happens in that case is that at some point they ask for a change in the precautionary measure. They say well, let’s see if it is. If we’re carrying out this trial, she can be free while the trial is carried out. And the judge denies it because she says she’s a poor woman who perhaps doesn’t have the economic means to get to the hearings. That’s the level of how surreal the case is. Well, finally, I accompany this whole process and it touches me a bit in real time, right? While I was writing the book, I was accompanying the process. What finally happens, at the end of this second trial, is that she is acquitted. Finally they acquit her. But the truth is that it happens in a context of a lot of media pressure, a lot, from many… When it starts, the judge in that last hearing, to speak, the truth is that everyone thought she wasn’t going to go free, right? Everyone thought that the sentence was going to be condemnatory, because she starts to speak and says that the evidence is there and that and others and she’s only grabbed onto a small thing to absolve the situation. What the judge says is like, Aurelia was alone at that moment, it can’t be proven what happened. And so, for that reason, reasonable doubt. We’re going to acquit her. But all the legal argumentation goes against. And that the lawyers told us, is very brutal, right? Because finally it prevents there being like a clear precedent on other cases of the same type.

Silvia: Aurelia was freed in December 2022.

Eliezer: We’re going to take one last break and when we return we’ll talk with Luciana about the situation of women who continue to be imprisoned for fortuitous abortions. We’ll be right back.

Eliezer: We’re back.

Silvia: What’s happening with the cases of women who continue to be imprisoned? Can they use as an argument this Supreme Court decision that now abortion is decriminalized? Or actually not, because they’re imprisoned for homicide?

Luciana: Well yes, technically no, let’s say. I do think that finally all the legal framework we have now, that we didn’t have five or 10 or 15 years ago, evidently improves the situation so that women can face justice. Legally and directly no, they can’t say well, since 2021 the Supreme Court of Justice said that the absolute prohibition of abortion is unconstitutional, because actually… Exactly right? They’re sentenced for other crimes. Of course that context allows women to have many more defense tools, in the organizations, in the accompaniment, even in public opinion, which is not at all minor. But it’s not that there’s a completely direct relationship, and in fact I was talking with an activist called Ninde MolRe, who is accompanying a case in Yucatán, which is truly something I didn’t see in all this time and which is crazy and interesting. It’s a mother and her daughter. Rocío is the mom, she has a 13-year-old daughter, the daughter becomes pregnant, asks for support to help her have an abortion and she says, and this seems very important to me, she says “I had read that abortion was already legal, so I well I helped my daughter have an abortion because I had already read that abortion could no longer be criminalized.” And so she helps her. She feels bad two days later. So the grandmother takes her to a medical center and when they arrive at this medical center they ask her too many questions, they find out what happened. She is placed under State guardianship, the girl, and they open a file against the mom for attempted femicide. So, let’s say, all these things continue happening. There’s a better environment, there’s a better legal framework, there’s a better, there’s a much less punitive environment. Yes, there is. What would be missing, and for me this is very important, is the legalization of abortion in all the federal entities, because finally abortion is something that’s addressed from the local level. So, both the unconstitutionality of the absolute prohibition and what came after, which was like the federal legalization of the Federal Penal Code, are very important, but let’s say, what’s necessary is that all the local penal codes of the federal entities homologate their Penal Code and take it out. Take abortion out of the Penal Code, right? I mean, basically that’s what should come in legal terms. Now, these other cases unfortunately continue happening and we’ve had a couple of examples even recently.

Eliezer: A recent case that received a lot of media coverage is that of Esmeralda, a girl from the state of Querétaro, 14 years old. A relative raped her and she filed a complaint. But the investigation was closed because according to justice there wasn’t enough evidence to punish the rapist.

Luciana: And they also say that she, a 14-year-old girl, had incurred some contradictions when giving her testimony. Because of this sexual violence she becomes pregnant and what happens is that she has an obstetric emergency. She has a health issue, has a fortuitous birth, the pregnancy is lost, the product is lost. And again they open a file for homicide. In her case it was intentional homicide. And they were also asking for 500,000 pesos in damage reparation for the rapist because he was the progenitor, let’s say, of the product in gestation. And that’s something that happens on many occasions. In addition to the prison sentence. Damage reparation is requested for the male progenitor of the product, right? And if there’s something that’s absent in all these stories, the truth, it’s the progenitors, they don’t appear at any moment. Or they appear only to say no, who knows if it’s mine, goodbye. We didn’t talk again. This appears in the investigation files.

Luckily this case becomes mediatic. And the organizations take it and it reaches the ears of the new Secretary of Women, Citlalli Hernández, because we also know that Querétaro is a particularly conservative State, in that sense. So, well, through dialogue, Citlalli Hernández manages to get the investigation file closed. At that moment I spoke with the lawyers from Adax Digitales, who were accompanying the case, and then I spoke with the secretary, with Citlalli Hernández and well, I asked her what happens with this other case, right? What happens with the rape case? And she told me that well, they had to wait for the victim’s timing if the victim wanted to restart the legal process, because we know that requires a very, very terrible emotional drain, right? So. Well, in this case, let’s say, it’s resolved, so to speak, but only because of the mediatization it had, because the secretary took it individually, because they didn’t take it out for a legal issue, there wasn’t a legal resolution. A political resolution, welcome it may be well. But let’s say, this can continue happening again and again.

Silvia: Luciana works in newscasts, covering daily news, so she gets cases with headlines like: “Mother murders her newborn baby in Tijuana and keeps it in the refrigerator.”

Luciana: And so, when I start reading, everything seems to indicate that it was an obstetric emergency in a bathtub, that she didn’t know she was pregnant. She grabs a knife to cut the umbilical cord that obviously she’s in an absolute state of shock. Imagine if one doesn’t know one is pregnant, has an obstetric emergency while bathing and doesn’t know what to do with the product and so keeps it, let’s say. And she goes to turn herself in also, to the authorities. That’s what happens. She goes to turn herself in. The woman was already linked to the process. But they are those cases –of course, I don’t have more context than that– But they are those cases where I always say hey, wait, murderous mother, wait. We have to see what’s happening with that woman. What’s her context? How did she get there? What’s happening? Was it born alive or wasn’t it born alive? How can you assure it was born alive? Anyway, let’s say. The truth is that these cases continue happening.

Silvia: And now Mexico has a female president. She’s left-wing. In Esmeralda’s case, she said: a 14-year-old girl shouldn’t be criminalized. She said she didn’t agree with the Prosecutor’s Office. But is it enough? I mean, what needs to happen in Mexico so that cases like Esmeralda’s and those from your research aren’t repeated?

Luciana: Well the world would have to change, Silvia. No, I don’t know, let’s say. I think there’s no definitive answer. I think they’re small steps that one takes. I would say the first thing is to conquer the decriminalization of abortion in the 32 federal entities. That I think is very important. From there, all the work that should be done in education. Exactly to combat what we were talking about a while ago: the fear of health personnel of committing a crime if they don’t report a possible abortion. And there’s another counterpart that also has to do with strengthening or changing the criminal justice system. What’s certain is that in Mexico we don’t only have a problem of this nature, but a problem of impunity, but a problem of inequalities. Yes the whole framework would have to change for us to be able to assure ourselves that these cases no longer exist.

Then a whole cultural change would have to come. Because also, let’s say, all this happens because there are people who belong to that justice system who really believe in what they’re saying. The police who arrive to attend to the crime, the complaint. They really believe that there’s a woman who is a murderer, and that therefore one must act against her. And reading also the brutal things that are said in those places… I remember the closing of one of the hearings where the Prosecutor’s Office starts its argument saying, “Mama, don’t kill me. That could have been what the baby said at the time of…” So, let’s say, all those people really believe in what they’re saying. It’s not just cruelty against women. There’s a deep belief that those women committed a crime. And they committed a crime against a defenseless person, moreover. And all this romanticized idea of motherhood and so on. But that cultural change is fundamental so that the people who participate in the processes don’t see the situation from that twisted and surreal perspective. The same with health personnel, the same with personnel who arrive to attend to the emergency. That is, it’s a whole chain where one only reaches the last instances inside a prison, when each link fails, so to speak, right?

I think the more we talk about it and the more we socialize it, the more we’re going to refine that gaze I was commenting on, right? And I think we can all be much more alert to try to differentiate when we’re talking about, I don’t know, a mother who got up and murdered her five-year-old son, from a woman who had an obstetric emergency and the product was lost in that process, right? But let’s say, I would think it’s a much more structural solution with many variables.

Silvia: Well, Luciana, thank you very much.

Luciana: Thank you, Silvia. What a pleasure.

Silvia: This episode was produced by me. Eliezer edited it. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design and music by Elías González.

The rest of El hilo’s team includes Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask you to join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to go deeper on today’s episode, subscribe to our email newsletter by going to elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it every Friday.

You can also follow us on our social networks. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook and Threads. You can find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share episodes.

I’m Silvia Viñas. Thanks for listening.