Lev Tahor

Secta

Guatemala

Colombia

Niños

Adolescentes

Ultraortodoxo

A finales de noviembre, las autoridades colombianas rescataron a 17 niños y adolescentes que estaban bajo el control de la secta judía ultraortodoxa Lev Tahor. Los líderes de este grupo enfrentan acusaciones de trata de personas, embarazo forzado y secuestro en varios países de la región. Durante la última década, han intentado establecerse en distintos lugares del continente: Estados Unidos, Canadá, México, Guatemala y ahora Colombia. Esta semana hablamos con el periodista guatemalteco Bill Barreto, que investigó sobre el origen de Lev Tahor y su presencia de más de diez años en su país, para entender cómo se han radicado en América Latina y por qué a Colombia le preocupa que intenten establecer una nueva colonia en el país.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Mariana Zúñiga -

Edición

Silvia Viñas, Eliezer Budasoff -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción en redes sociales

Samantha Proaño, Franklin Villavicencio, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Elías González, Remy Lozano -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

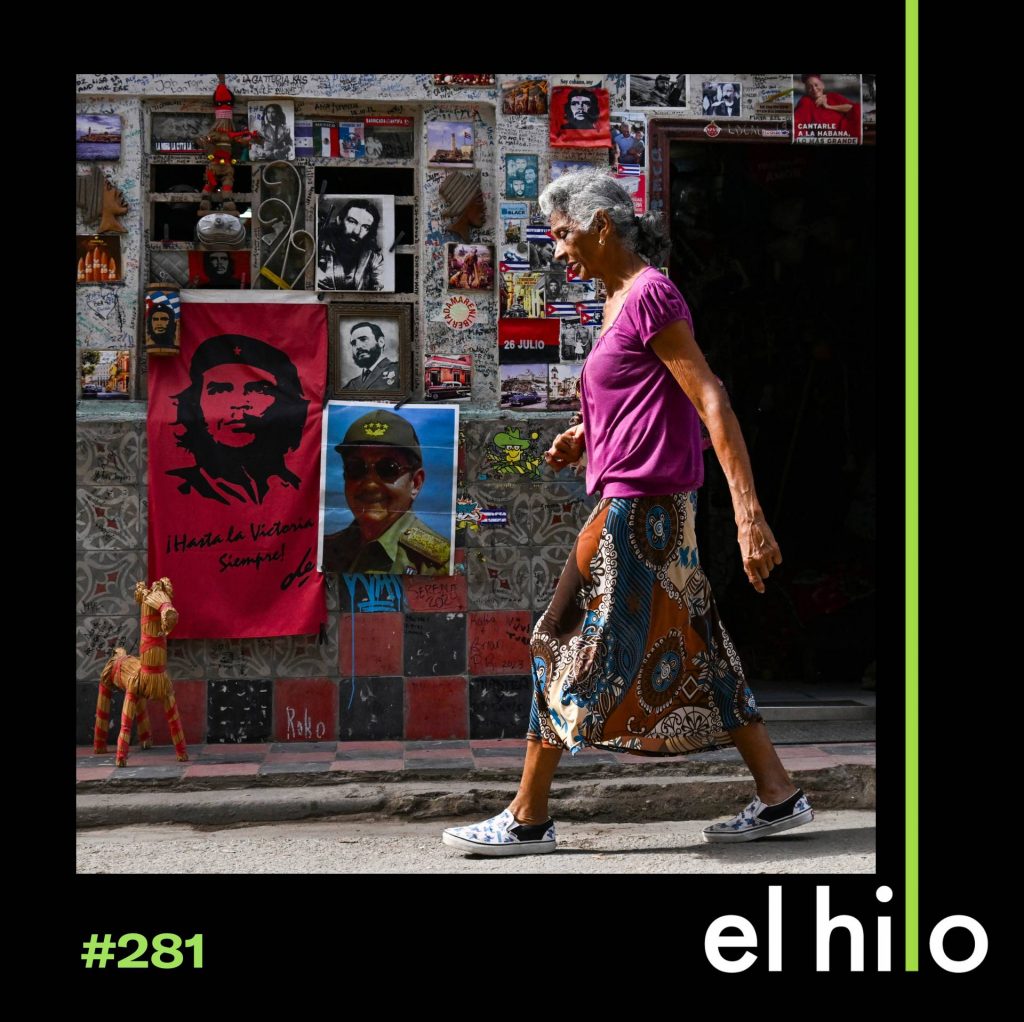

Fotografía

Getty Images / Johan Ordonez

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Silvia Viñas: Hola. Como te contamos la semana pasada, estamos en nuestra campaña de recaudación de fondos. Y es la más crítica del año. Son momentos difíciles en la región, pero en El hilo elegimos mirar el mundo tal como es, no mirar hacia otro lado. Lo hacemos porque sabemos que tú nos acompañas. Este periodismo existe porque personas como tú deciden que importa.

Eliezer Budasoff: Esta semana además, tenemos una gran noticia: NewsMatch va a duplicar las donaciones que recibamos. Si, por ejemplo, nos donas 15 dólares, vamos a recibir 30. Entonces, si valoras el periodismo que hacemos, este es el momento para ayudarnos. Entra a elhilo.audio/donar. Todo monto, por más pequeño que sea, cuenta. ¡Muchísimas gracias!

Silvia: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: Y yo soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Audio de archivo, presentador: Un operativo de las autoridades colombianas liderado por migración Colombia logró rescatar a 17 menores de edad que estaban secuestrados por la secta ortodoxa Lev Tahor.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: Entre esos menores de edad hay cinco que tienen circular amarilla, es decir, que están siendo buscados en otros países.

Eliezer: En los últimos diez años, esta secta judía llamada Lev Tahor, ha tratado de asentarse en diferentes países de América. Colombia es el sexto país por el que pasan, pero también han estado en Estados Unidos, Canadá, México y Guatemala. En todos, sus líderes enfrentan acusaciones de trata, embarazo forzoso, secuestro, entre otros delitos.

Silvia: Hoy vamos a Guatemala, donde estuvieron más de una década, para entender cómo se ha radicado Lev Tahor en América Latina y por qué a Colombia le preocupa que intenten instalar una nueva colonia en el país. Es 5 de diciembre de 2025.

Silvia: Las noticias recientes se suman a los titulares que aparecen cada tanto sobre este grupo en la región. En 2018, por ejemplo, dos líderes de Lev Tahor fueron detenidos en un pueblito de México. Habían raptado a dos menores en Nueva York para llevarlos de vuelta a Guatemala, donde estaban establecidos.

Eliezer: Bill, para alguien que nunca escuchó hablar de Lev Tahor, ¿cómo lo definirías?

Bill Barreto: Bueno, es un grupo ultraortodoxo surgido a finales de los años 80 en Israel que, alrededor de una figura carismática, comenzó a crear un verdadero grupo sectario. El cual, tras ser expulsado de Israel y asentarse primero en Estados Unidos y luego en Canadá, terminó operando como por más de diez años en Guatemala.

Silvia: Él es Bill Barreto, periodista de No Ficción, un medio guatemalteco. Hablamos con él porque investigó a este grupo y hace poco publicó una serie de podcast que explora quiénes son y cómo llegaron al país.

Bill: Y siendo todos conducidos por un líder carismático que los incitaba a tener una práctica del judaísmo originario, según ellos, que es prácticamente bastante restringido en cuanto a su contacto con el resto del mundo y que, bueno, durante aproximadamente una década en Guatemala operaron, crecieron, reclutaron a más personas y que finalmente bueno, el grupo en buena medida fue desarticulado el año pasado, cuando hubo una intervención de parte de las autoridades guatemaltecas por las denuncias previas de violaciones de derechos de menores.

Eliezer: Las autoridades guatemaltecas y los medios definen a Lev Tahor como una secta judía ultraortodoxa.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: Miembros de la secta Lev Tahor

Audio de archivo, presentadora: La secta judía ultraortodoxa Lev Tahor

Audio de archivo, presentadora [en inglés]: Una marginal secta judía fundamentalista, llamada Lev Tahor.

Eliezer: ¿Qué caracteriza a este grupo para llamarlo secta?

Bill: Una de las características, claro, es que sea un grupo que tiene prácticas coercitivas que lo separan del resto de la sociedad, que mira en el resto de la comunidad donde viven a un grupo que les puede ser hostil, que es dirigido por una figura carismática o por muy pocas personas que marcan las reglas de conducta de toda la comunidad y tienen medidas estrictas para las personas que no los cumplan, y de alguna manera los condicionan a segregarse, a apartarse de cualquier contacto.

Eliezer: Al comienzo contabas un poco de esto, pero ¿qué se sabe de los orígenes de Lev Tahor? Tú decías que fueron expulsados de Israel.

Bill: Sí, realmente bueno, en Israel hay diferentes grupos ultraortodoxos Y lo curioso es que algunos de estos grupos en particular son antisionistas, en el sentido de que no consideran que el Estado de Israel tiene que ser creado. Y dentro de esos grupos estaba el que creó Shlomo Helbrans, el fundador de este grupo a finales de los años 80, y el mismo Estado los consideró de alguna manera peligrosos al promover estas ideas y también al promover los matrimonios entre menores, que también choca con la legislación de allá.

En los 90 se van a Estados Unidos, ahí comienzan a crear un poco más la comunidad, hacerla más grande, siempre dentro de la comunidad, dentro de la comunidad ortodoxa, pero apelando a que no, nosotros somos más fieles al pie de la letra de nuestras escrituras y atrayendo a personas que ya eran de fe judía pero que buscaban una versión más estricta de esta fe. Y así van radicalizándose de alguna manera. Pasan de Estados Unidos a Canadá. En Canadá también, los servicios sociales advierten que hay riesgos para los menores y los intervienen. Y ahí es donde entre 2013 y 2014 comienzan a buscar opciones y miran Guatemala.

Incluso me comenta uno de sus líderes: nosotros fuimos a la embajada y ahí había alguien que nos dijo no, en Guatemala aceptamos a los judíos, nos encanta el Estado de Israel. Aquí pueden venir y claro, vieron una oportunidad. Dijeron bueno, vámonos. Encontremos ahí un lugar, un refugio. Y así es como se da este periplo, del grupo.

Eliezer: ¿Cuándo fue la primera vez que escuchaste hablar sobre este grupo y que pensaste en ese momento?

Bill: Sí, la primera vez que escuché hablar del grupo fue en el año 2014, cuando recién llegaron a Guatemala. Era algo bastante inusual porque aquí hay una comunidad judía convencional, pequeña, pero hay una comunidad judía. Pero ellos de alguna manera estaban llevando a cabo prácticas mucho más conservadoras en la vestimenta, en el contacto con el resto de la comunidad. Eligieron un municipio relativamente cercano en San Juan La Laguna, en Sololá, un departamento cercano, turístico. Y poco a poco, a lo largo de unos cuantos meses comenzaron a recibir más y más gente hasta que fueron alrededor de 200 personas más o menos. Y la comunidad, que es una comunidad maya tz’utujil, pues comenzó a sentir que estaban irrumpiendo de manera muy drástica en las tradiciones y costumbres locales y que eso comenzaba a generar tensiones.

Y en esta oportunidad, justamente una colega periodista ─que estaba haciendo un reportaje sobre la llegada de esta comunidad y el rechazo que había causado en algunos integrantes de este pueblo─ me pidió que la acompañara. Entonces la acompañé. Y pudimos hablar con una persona, un guatemalteco converso al judaísmo, a Lev Tahor, y que nos comenzó a contar bueno, ¿por qué me sentí atraído por este grupo? ¿Qué encontré ahí que me resultaba atractivo, diferente a mi fe anterior? Él era de una fe cristiana protestante y se había convertido al judaísmo. Y nos comenzó a explicar un poco de su fe y cómo creía que era volver a de alguna manera a sus raíces, por decirlo de alguna manera, a las raíces de su fe, el convertirse al judaísmo. Y ese fue mi primer contacto.

Y bueno, la comunidad no los estaba recibiendo. Entonces el Consejo de ancianos tz’utujil les pidió que se retiraran.

Audio de archivo, periodista: Son los Lev Tahor. 230 personas que han tenido que exiliarse por desavenencias con los habitantes indígenas locales. El consejo de ancianos de San Juan afirma que tomó la drástica decisión porque los ortodoxos rechazaban a los pobladores locales, negándose a saludar, mezclarse e incluso a hablarles.

Bill: Y se fueron a un departamento del oriente del país, a una finca que compraron. Y bueno, se fueron aislando.

Eliezer: Bill, durante tu investigación visitaste la finca donde Lev Tahor se estableció y estuvo una década. Descríbenos un poco el lugar: qué viste y qué impresión te dejó.

Bill: Si es una finca como a una hora y media de la ciudad capital dedicada sobre todo a la ganadería, algunos pequeños cultivos. Justo se encuentra sobre la carretera y uno puede pasar por ahí y tomarlo por cualquier granja que hay en la zona con sus grandes bodegas para almacenar, no sé, cualquier clase de insumo agrícola y demás. Puede pasar totalmente desapercibida. Pero, cuando uno entra ya en una de estas bodegas lo que se encuentra es muy peculiar.

Por ejemplo, una de esas bodegas es una especie de biblioteca-templo, donde la mitad está dedicada a una biblioteca de textos jasídicos y la otra mitad estaba utilizada para habitar. Y el área de vivienda. Simplemente es una serie de cubículos separados con plástico, donde muchas familias viven hacinadas. Luego hay otra bodega que era básicamente una panadería, una gran panadería. Luego, a su alrededor, estos campos para el ganado que, bueno, ahora ya se había limitado simplemente a cabras. Y bajo los árboles los maestros enseñaban a los niños, separando los niños de las niñas, inculcándoles su fe, hablándoles sobre sus tradiciones y bueno, también enseñándoles el idioma, ¿verdad? La práctica del yiddish. Aprendían por su cuenta un poco los niños, el español, cuando lo hablaban con algún trabajador cercano de la finca, porque también había algunos trabajadores guatemaltecos que apoyaban y ese era el día a día, el día a día de esta comunidad.

Silvia: Una pausa y volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Eliezer: ¿Cuándo empiezan las autoridades guatemaltecas a recibir denuncias sobre el grupo? ¿Y de qué tipo?

Bill: Hay diferentes momentos. Incluso en 2015, 2016 hay algunas primeras denuncias. Luego se intensifica en 2019, pero han sido constantes a lo largo de esos diez años. Ha habido denuncias sobre abusos, sobre forzar a los menores a contraer matrimonio con personas mayores o entre ellos mismos, entre menores, la promoción incluso de embarazos adolescentes. Personas que dejan la comunidad, que fueron integrantes y que, por ejemplo, tenían otra nacionalidad como canadiense o estadounidense, y al regresar a sus países venían y denunciaban en el exterior, que este grupo les había restringido sus libertades, que todavía tenían familiares ahí. Hermanos, hermanas, padres que vivían sometidos. Pero las autoridades guatemaltecas en ese período, y te hablo de 2014, 2019, hacían muy poco.

Y aquí hay que poner como un punto de contexto sobre por qué no, ¿verdad? Y es que también hay que pensar que las autoridades guatemaltecas, también en ese período, el Ejecutivo y demás, eran gobiernos muy conservadores que tenían esta dicotomía bien extraña de un gran respeto por Israel. Todo lo que era judío era bueno, aunque muchas veces ni siquiera se ponían a ver el detalle de: ah, pero en realidad ellos también son antisionistas. No están de acuerdo con el Estado de Israel.

Eliezer: Claro, tenían miedo de ser vistos como que estaban persiguiendo a judíos simplemente, digamos, ¿no? por ser diferentes.

Bill: Claro, que los calificaran como antisemitas. Hubiera hecho estallar ahí unas alertas importantes, porque si miraban, digamos, en esa comunidad y en ese país, en ese país en particular, un aliado, un aliado estratégico. Aquí eran percibidos como los judíos. Y cuando le preguntabas a alguien, a un alcalde, a una autoridad local, ¿quiénes son ellos? Ellos son los judíos. Estaba, digamos, en el imaginario, en el imaginario social, esa denominación, ¿verdad?

Luego en 2024…

Audio de archivo, presentadora: En noviembre cuatro menores escaparon de una granja amurallada en Guatemala. Eran de la secta Lev Tahor. Lograron llegar al Ministerio Público y denunciar los abusos que sufrían.

Bill: Hay una denuncia que hace este adolescente que se ha fugado, dice que fue obligado a casarse y que la menor todavía sigue en la comunidad. Alguien más sale y denuncia “No, pero mis hermanos todavía siguen estando adentro y los están cohibiendo”. Los están forzando a tener esta fe o a no poder salir del grupo. Entonces durante 2024 se dieron estas visitas recurrentes y cada vez fue escalando, hasta que finalmente llegan a un punto en el que dicen bueno: vamos a intervenir.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: Las autoridades guatemaltecas rescataron a 160 niños y adolescentes de la polémica secta judía de Lev Tahor.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: En el allanamiento fueron encontradas tumbas y se confiscaron numerosos dispositivos electrónicos.

Audio de archivo, fiscal: Se sospecha la posible comisión de delitos de trata de personas y algunos otros delitos. Específicamente en la modalidad de embarazo forzado…

Bill: En 2024, en diciembre de 2024, se produce un operativo bastante grande donde vienen con estos 600 policías y estos agentes a derrumbar el portón y extraer a los menores. Y en escenas que son bien dramáticas, los niños ahí llorando. Y ¿quiénes son estos hombres de negro que me vienen y me extraen, que me llevan? Además hay que considerar otra cosa. Durante años a esta comunidad, sus padres les han inculcado que el exterior es enemigo, el exterior no te quiere, te odia. Tú eres diferente, te van a perseguir.

Entonces, al darse esta intervención del Estado, para ellos fue como romperles la burbuja y fueron extraídos de ahí y expuestos a otro mundo, ¿verdad? Y claro, en el caso de Guatemala también hay que tenerle mucha atención al tema del resguardo de los menores, porque no hay garantías de que estén en buenas condiciones en los centros de acogida. Y creo que hay que tener atención sobre este tema.

Eliezer: Los fiscales dijeron que sacaron al menos 160 niños y adolescentes de esa finca, ¿no? Después del allanamiento, ¿Qué pasó con esos niños? ¿A dónde se los llevaron?

Bill: Después de sacarlos de la finca, del complejo, los llevaron a centros de acogida en Ciudad de Guatemala, a refugios infantiles, mientras comenzaban en cada caso una serie de procesos para decidir quién iba a tener la custodia de esos menores, si tenían otros familiares fuera de sus padres o sus madres del complejo que pudieran atenderlos. Y te hablo de más de 160 niños en ese primer momento, pero luego iban encontrando otros menores que a lo mejor estaban en otra casa paralela, cercana, y volvía a haber otra intervención y llegaban y estos niños y niñas llegaban a los centros de acogida. Al principio estaban casi todos reunidos en un solo centro y al final era bastante complejo atenderlos porque incluso el mismo Estado no tenía las capacidades para cubrir sus necesidades alimentarias.

Audio de archivo, presentador: Una de las madres denuncia que el Estado no alimenta a su hija con la dieta judía Kosher.

Audio de archivo, madre [en inglés]: Ella comía así, como si no hubiera comido en varias semanas.

Bill: Hubo un grupo de madres, más de 50 madres, que estuvieron durante semanas ahí preparándoles algunos alimentos. Luego las mismas autoridades las sacaron a la fuerza en un operativo, porque comenzó a filtrarse esta denuncia de que había un posible suicidio colectivo que las madres podrían organizar y que era un riesgo, que podían llegar a atentar contra la vida de los menores. Y redistribuyen a los niños a lo largo de diferentes centros a lo largo de la ciudad de Guatemala, como para evitar que estén todos concentrados en un solo sitio.

Y en paralelo, cada familia, cada grupo anda con su propio proceso para recuperar custodia. Algunos no lo consiguen. Entonces los menores van con familiares en Estados Unidos, en Israel. Otros, si lo consiguen, tienen que pasar por un proceso de meses de audiencias, de visitas, consultas con psicólogos y demás, para probar de alguna manera de que ya no están siendo coercitivos con los menores y que van a respetar las normas legales del país, siempre dentro de su fe, porque eso obviamente no lo puede perseguir el Estado, en Guatemala está garantizada la libertad religiosa. No los pueden perseguir por su fe. Y eso sería una flagrante violación de los derechos humanos. Pero lo que sí tienen que hacer es garantizar que dentro de sus prácticas culturales, no haya acciones que violenten sus derechos, que los expongan a riesgos. Y bueno, eso como te digo, más de 160 menores en diferentes procesos, esparcidos a lo largo de diferentes juzgados de familia.

Silvia: Esto también fue un disparador para que Bill decidiera investigar más en profundidad la presencia de Lev Tahor en Guatemala. Porque había algo más detrás de los titulares. Recordemos que el grupo estaba radicado en el país desde hacía una década.

Bill: Veía constantemente de que se estaba dando un seguimiento a los procesos de la custodia de los menores, del resguardo, pero mi impresión era que seguíamos estando únicamente en el hecho escandaloso o noticioso de estos menores están extraídos de esta comunidad, han sido llevados por el Estado, pero no nos preguntábamos qué significa esto, por qué esta gente llegó acá, qué condiciones incluso consideraron que Guatemala les hacía un lugar ideal para venir y asentar su comunidad. Y luego, cuando pude hablar con ellos, justo me encontré con algo que me parecía que era relevante, que es que me decían no, es que nosotros, nuestra idea era que en Guatemala se podía hacer esto, que había una buena recepción de judíos y ustedes igual también tienen esta situación, hay menores que se embarazan. Entonces, este era un lugar ideal para nosotros. Y de alguna manera eso me pareció chocante, ¿verdad? Dije bueno, es interesante comprenderlo.

Silvia: Hacemos una última pausa y volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta.

Eliezer: Tú hablaste con alguien que pertenece a esta organización.

Audio de archivo, Miriam Weingarten: Nosotros escuchamos que Guatemala es un buen país, libre para la religión, gente buena que le gustan judíos, les gusta Dios.

Eliezer: Cuéntanos sobre ella y qué te contó sobre las denuncias en contra de Lev Tahor. ¿Qué alegan ellos?

Bill: Si, yo hablé con Miriam Weingarten, que es esposa de uno de los líderes del grupo y que justo cuando hablé con ella acababa de recuperar, tenía menos de una semana de haber recuperado la protección, la custodia de sus hijos, de seis niños. Y justamente al preguntarle directamente si ellos consideraban que eran una secta y que podía poner en peligro a sus integrantes, lo niegan rotundamente. Dicen: no, no somos una secta, solo somos un grupo de judíos que trata de vivir según las reglas de la Torá. Son los demás, los que nos persiguen. Nosotros no, no violamos derechos.

Eliezer: ¿Y dónde están ahora los miembros Lev Tahor? Porque me cuentas toda esta odisea de los niños, 160 dispersos, niños y adolescentes. Pero ¿qué pasó con ellos? Con los adultos.

Bill: Los adultos están en su mayoría dispersos a lo largo de la ciudad de Guatemala y unos pocos todavía en la comunidad de Lev Tahor en Oratorio, Santa Rosa, en este pequeño pueblo donde se asentaron. Pero la mayoría están dispersos a lo largo de la ciudad de Guatemala, porque muchos siguen en procesos judiciales por la custodia de los menores. Los han ido recuperando. Entonces viven en casas, en apartamentos, algunos alquilan acá algunos lugares muy precarios, otros lugares ya con más recursos y en ocasiones, incluso caminando, te puedes encontrar algún integrante. Lo reconoces fácilmente porque usan la vestimenta estricta que es muy característica, en tonos, cafés y demás. Yo me los he encontrado a veces en las cortes, haciendo algún trámite judicial por el tema de la custodia de sus hijos, pero sí, los encuentras dispersos en diferentes lugares de la ciudad, algunos sí se han retirado, han regresado con sus familias en Estados Unidos, en Canadá o en Israel.

Eliezer: Pero ninguno de los responsables adultos de la comunidad tiene o ha tenido procesos judiciales. O sea, ¿no les han puesto cargos?

Bill: Hay algunos integrantes de la comunidad que sí están procesados. La última vez que pude actualizar había siete, si no estoy mal, con procesos judiciales activos. Incluso ha habido extradiciones de El Salvador a Guatemala de un caso. Y sí, hay procesos penales activos en Guatemala, ya sea por trata de personas, al trasladar incluso por las fronteras de los países a menores, o por abuso físico a menores, porque también se reportan castigos físicos y demás en algunos casos. Y también por abuso sexual, que hay al menos un caso que está avanzando en esa materia por abuso sexual, de un mayor, de un adulto hacia un menor. Entonces sí hay casos activos que todavía están en proceso.

Audio de archivo, reportera: Durante un mes las autoridades realizaron el seguimiento de esta secta aquí en Colombia.

Audio de archivo, reportera: En Yarumal, un pequeño pueblo campesino y ganadero de Antioquia de apenas 45.000 habitantes, nadie sospechaba nada.

Eliezer: A finales de noviembre las autoridades colombianas rescataron a 17 niños y adolescentes que estaban bajo el control del grupo.

Audio de archivo, reportero: Es la primera vez que un tipo de intervenciones de esta secta se realiza aquí en Colombia. Los menores de edad que están bajo custodia del ICBF están bien de salud. Es una noticia en desarrollo. Al momento las autoridades están investigando.

Eliezer: En Colombia, la presencia de la secta tiene preocupadas a las autoridades, porque claro, se cree que están tratando de reconstruir su comunidad y continuarla en ese país. ¿Crees que es posible lo que pasó en Guatemala, pero en Colombia?

Bill: Creo que se ve ahí cierto patrón, que es buscar, justamente, los márgenes dentro de los Estados o de sociedades que tampoco logran garantizar del todo los derechos de sus de sus mismas poblaciones. Y que sí, están buscando un espacio donde puedan recrear de alguna manera lo que tuvieron durante más de diez años en Guatemala. En cierta medida, cierta impunidad para algunas prácticas y por eso están buscando un Estado y justo, ciertos márgenes de la sociedad, donde puedan reconstruir sin llamar tanto la atención.

Y lleva a pensar también cómo pasan las fronteras y en algunos casos menores, con procesos abiertos, con órdenes de arraigo, de juez. Entonces aquí una vez más, lo que se ve es la vulnerabilidad de las instituciones acá, ¿verdad? Guatemala, Honduras, Colombia es donde se puede transitar muchas veces sin mayores controles. Y como claro, si vas de norte a sur no te miran de mayor cosa, aplican de otra forma los controles migratorios y claro, las instituciones de la región están plagadas de corrupción, eso hay que reconocerlo. Entonces, algo así es muy palpable y les puede dar en general las condiciones como para buscar su refugio en otro país, como en este caso Colombia.

Eliezer: ¿Tú crees que tienen posibilidades de desaparecer?

Bill: Lo veo muy difícil. O sea, mientras quede un par de personas con esta fe tan férrea, mientras sigan creyendo en su doctrina de esta manera y consigan atrayendo apoyos, pues van a seguir pudiendo reclutar gente. Y algo curioso es que por ejemplo, al preguntarles a algunos integrantes cómo se incorporaron, todos venían de familias judías tradicionales ortodoxas. Incluso en el caso de Miriam, tenía un abuelo que había sido rabino y todo, pero no tenía una práctica radicalizada. Y lo que me decían es que encontraban en esta fe lo que estaban buscando. Había algo ahí que los alimentaba, una necesidad de absoluto, por decirlo de alguna manera.

Bill: Y mientras exista esa necesidad y ese vacío existencial en diferentes comunidades, van a tener materia prima de donde atraer gente. Entonces creo que eso habla también un poco de esa necesidad que hay muchas veces en nuestras sociedades, de sentido y de comunidad. Y eso es lo que ofrecen grupos como Lev Tahor, ese sentido de comunidad.

Silvia: A principios de diciembre, el gobierno colombiano expulsó del país a nueve personas de la secta Lev Tahor y entregó a los 17 niños y adolescentes que iban con ellos a las autoridades de Estados Unidos.

Mariana: Este episodio fue producido por mí, Mariana Zúñiga. Lo editaron Silvia y Eliezer. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido es de Elías González con música suya y de Rémy Lozano.

Queremos agradecer a Bill Barreto por dejarnos usar un extracto de su podcast Lev Tahor: Guatemala, la tierra prometida. Lo pueden encontrar en el sitio web no-ficcion.com.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Samantha Proaño, Franklin Villavicencio, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Silvia Viñas: Hello. As we told you last week, we’re in our fundraising campaign, and it’s the most critical one of the year. These are difficult times in the region, but at El hilo we choose to look at the world as it is, not to look away. We do this because we know you’re with us. This journalism exists because people like you decide that it matters.

Eliezer Budasoff: This week, we also have great news: NewsMatch is going to double the donations we receive. If, for example, you donate 15 dollars, we’ll receive 30. So if you value the journalism we do, this is the time to help us. Go to elhilo.audio/donar. Every amount, no matter how small, counts. Thank you so much!

Silvia: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: And I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Archive audio, host: An operation by Colombian authorities led by Migración Colombia managed to rescue 17 minors who had been kidnapped by the Orthodox sect Lev Tahor.

Archive audio, host: Among those minors, there are five who have yellow notices, meaning they’re being sought in other countries.

Eliezer: Over the last ten years, this Jewish sect called Lev Tahor has tried to settle in different countries across the Americas. Colombia is the sixth country they’ve passed through, but they’ve also been in the United States, Canada, Mexico, and Guatemala. In all of them, their leaders face charges of trafficking, forced pregnancy, kidnapping, among other crimes.

Silvia: Today we’re going to Guatemala, where they spent more than a decade, to understand how Lev Tahor has established itself in Latin America and why Colombia is concerned that they may be trying to set up a new colony in the country. It’s December 5th, 2025.

Silvia: Recent news adds to the headlines that appear from time to time about this group in the region. In 2018, for example, two Lev Tahor leaders were arrested in a small town in Mexico. They had kidnapped two minors in New York to take them back to Guatemala, where they were based.

Eliezer: Bill, for someone who’s never heard of Lev Tahor, how would you define it?

Bill Barreto: Well, it’s an ultra-Orthodox group that emerged in the late 1980s in Israel which, around a charismatic figure, began to create a true sectarian group. After being expelled from Israel and settling first in the United States and then in Canada, it ended up operating in Guatemala for more than ten years.

Silvia: He is Bill Barreto, a journalist from No Ficción, a Guatemalan media outlet. We spoke with him because he investigated this group and recently published a podcast series that explores who they are and how they came to the country.

Bill: And all being led by a charismatic leader who urged them to practice original Judaism, according to them, which is quite restricted in terms of their contact with the rest of the world. And well, for approximately a decade in Guatemala, they operated, grew, recruited more people, and finally, the group was largely dismantled last year when there was an intervention by Guatemalan authorities due to previous complaints of violations of minors’ rights.

Eliezer: Guatemalan authorities and the media define Lev Tahor as an ultra-Orthodox Jewish sect.

Archive audio, host: Members of the Lev Tahor sect

Archive audio, host: The ultra-Orthodox Jewish sect Lev Tahor

Archive audio, host [in English]: A fringe fundamentalist Jewish sect called Lev Tahor.

Eliezer: What characterizes this group for it to be called a sect?

Bill: One of the characteristics, of course, is that it’s a group that has coercive practices that separate it from the rest of society, that views the rest of the community where they live as a group that can be hostile to them, that is led by a charismatic figure or by very few people who set the rules of conduct for the entire community and have strict measures for people who don’t comply with them, and that somehow conditions them to segregate themselves, to stay away from any contact.

Eliezer: At the beginning you were talking a bit about this, but what is known about the origins of Lev Tahor? You said they were expelled from Israel.

Bill: Yes, well, in Israel there are different ultra-Orthodox groups, and what’s curious is that some of these groups in particular are anti-Zionist, in the sense that they don’t consider that the State of Israel should have been created. And within those groups was the one created by Shlomo Helbrans, the founder of this group in the late 1980s, and the State itself considered them somehow dangerous for promoting these ideas and also for promoting marriages between minors, which also clashes with the legislation there.

In the 90s they moved to the United States, where they began to build up the community a bit more, make it bigger, always within the Orthodox community, but claiming that no, we are more faithful to the letter of our scriptures and attracting people who were already of the Jewish faith but who were looking for a stricter version of this faith. And so they became increasingly radicalized in a way. They went from the United States to Canada. In Canada as well, social services warned that there were risks for minors and intervened. And that’s when, between 2013 and 2014, they began to look for options and looked at Guatemala.

One of their leaders even told me: we went to the embassy and there was someone there who told us, no, in Guatemala we accept Jews, we love the State of Israel. You can come here, and of course, they saw an opportunity. They said, well, let’s go. Let’s find a place there, a refuge. And that’s how this journey of the group came about.

Eliezer: When was the first time you heard about this group and what did you think at that moment?

Bill: Yes, the first time I heard about the group was in 2014, when they had just arrived in Guatemala. It was something quite unusual because there is a conventional Jewish community here, small, but there is a Jewish community. But they were somehow carrying out much more conservative practices in dress, in contact with the rest of the community. They chose a relatively nearby municipality in San Juan La Laguna, in Sololá, a nearby, touristy department. And little by little, over the course of a few months, they began to receive more and more people until there were around 200 people or so. And the community, which is a Tz’utujil Maya community, began to feel that they were disrupting the local traditions and customs very drastically and that this was beginning to generate tensions.

And on this occasion, a fellow journalist—who was doing a report on the arrival of this community and the rejection it had caused among some members of this town—asked me to accompany her. So I accompanied her. And we were able to talk to a person, a Guatemalan convert to Judaism, to Lev Tahor, who began to tell us, well, why did I feel attracted to this group? What did I find there that I found attractive, different from my previous faith? He was from a Protestant Christian faith and had converted to Judaism. And he began to explain to us a bit about his faith and how he believed it was returning in some way to his roots, so to speak, to the roots of his faith, by converting to Judaism. And that was my first contact.

And well, the community wasn’t welcoming them. So the Tz’utujil Council of Elders asked them to leave.

Archive audio, journalist: They are the Lev Tahor. 230 people who have had to go into exile due to disagreements with the local indigenous inhabitants. The Council of Elders of San Juan says it made the drastic decision because the Orthodox rejected the local population, refusing to greet them, mingle with them, or even speak to them.

Silvia: A few months later they moved to another town.

Bill: Eventually they found a place in Oratorio, Santa Rosa, where the mayor, a local pastor, offered them some properties and they began to settle there. And they settled more permanently in that place. And they spent approximately ten years in that place where they flew somewhat under the radar. That is, there wasn’t much mention in the media. Very little was heard. And the group was growing. They continued to bring people in, recruiting people.

Eliezer: What was the community’s life like? What did they do?

Bill: Well, in their daily life they said: we live according to the Torah. That is, the first five books of the Bible, which is the book that guides and shapes our lives. And they spent the day studying the Torah. They had a rabbi who guided them, who gave them classes. Women were always segregated in their tasks and activities. Men also had their own spaces. And very little contact with the outside. That is, if they had to go out to do shopping, for example, if they had to go out to make some purchases in the town, the men went out, and they usually went out only to buy food and, well, basic things.

Eliezer: And in all that time they lived in Oratorio, was there no concern at the institutional level?

Bill: At the institutional level they passed rather unnoticed because they didn’t cause any tension with the community where they lived. The community accepted them. And on the part of the State, well, they paid their taxes, they acquired properties. That is, they operated legally and formally. So they didn’t raise any alarms. However, there were some concerns internationally because some organizations and institutions abroad warned that there were investigations and that people from Lev Tahor had already had run-ins with the justice system in the United States and Canada, due to complaints about child marriages, about child trafficking, about situations of child abuse. And some institutions like the United States embassy apparently did make some inquiries at the Guatemalan foreign ministry level, but no intervention was ever carried out at that time with them. In fact, some of the officials who worked on these cases told me that they couldn’t act because there were no local complaints. That is, for them to intervene, there needed to be a local complaint, a formal complaint. And there wasn’t one. So they didn’t act.

Silvia: We’ll take a break and be right back.

Archive audio, host: Two young men, brothers, managed to escape from the Lev Tahor community, because according to their testimony they were victims of abuse and mistreatment within that religious sect.

Silvia: We’re back on El hilo.

Eliezer: So what happened for them to finally receive complaints and for authorities to intervene?

Bill: Basically what happened was that in 2023 some former members who had managed to escape from the group began to make formal complaints before Guatemalan authorities. Among these former members there were three young people, including the case of Tzvi, who was a young man, an adolescent of about 17 years old, who managed to escape and went to the prosecutor’s office of the Public Ministry to say: look, I’m a victim of mistreatment by this group. I need your help.

And the prosecutor’s office attended to him and began to investigate and verify the information, and found that indeed there were complaints from abroad from other former members, from other countries.

Eliezer: And what did they say happened? What did they experience?

Bill: Well, in Tzvi’s case, for example, he said that since he was a child he had been mistreated, that there was physical punishment, that they forced him to study only the Torah and didn’t allow him access to any other type of educational content or to relate to other people outside the group. That the disciplinary regime was very rigid and very extreme. He said he had been beaten. And he said that, for example, some girls were forced to marry very young, at 12 or 13 years old, and to become pregnant.

And well, that alerted the authorities and they began to investigate more deeply. And it wasn’t only Tzvi’s testimony, but several former members, some from abroad, who also gave their testimonies. And what the authorities did was coordinate an intervention operation.

Archive audio, host: In a joint effort by different institutions, a raid was carried out at the facilities where members of the Lev Tahor sect operate. Members of the Public Ministry and the National Civil Police participated in this raid.

Bill: And this is where something very important happens. The Guatemalan State not only carried out a raid but also said: we’re going to remove all the minors, we’re going to place them under State protection because we consider that they are at risk. And that was where this massive separation of families occurred.

Archive audio, host: A total of 160 minors were taken from the Lev Tahor religious sect. These minors are now under state protection since they were living in a situation of risk.

Eliezer: 160 children and adolescents were separated from their parents. You talked with some people from Lev Tahor. What did they think about this action by the State?

Bill: Well, yes, I talked with one of the leaders and he told me: look, what happens is that the world doesn’t understand us. We practice our religion as we consider it should be practiced. And the people who complain are traitors who abandoned the faith and now want to harm us. So they deny that there are abuses, deny that there is mistreatment. They say everything is part of their religious practice and that the State has no right to intervene.

And regarding the minors, they claim that the separation has been traumatic for the children, that it has been an act of cruelty, because the children were taken from them, the families say, violently, traumatically, and placed in State shelters where they were treated poorly and where their religious practices weren’t respected.

Eliezer: And what has the process been like after the raid?

Bill: Well, after the raid what happened is that the 160 minors were placed in different shelters and institutions throughout the country. And the parents began a legal process to recover custody of their children. And what has happened over time is that the courts have been returning custody of some children to the parents, but always with conditions. That is, the judges say: okay, we’re going to return your children but you have to commit to sending them to school, to taking them to health check-ups, to allowing them to have contact with the outside world.

And in some cases the judges have said: we can’t return custody to you because we consider there’s still a risk. So there are still minors who are under State protection and there are families that haven’t been able to recover their children.

Silvia: And what drew them to Guatemala?

Bill: Well, what one of the leaders told me is that they looked for a place where they could practice their faith freely and where they wouldn’t be bothered. Guatemala seemed like an ideal place because there’s a certain tolerance for religious diversity, because there are many evangelical churches, many different religious groups. And also because the State has little presence in rural areas. That is, if you go to a rural community far from the capital, the State barely has a presence there. So for them it was an ideal place. They told me literally: look, here in Guatemala no one asks questions, here we can live our way and no one bothers us. And also because Guatemala is a country where child marriages are still common in some communities, where there are minors who become pregnant. So this was an ideal place for us. And somehow that struck me, right? I said, well, it’s interesting to understand it.

Silvia: We’ll take one last break and we’ll be back.

Silvia: We’re back.

Eliezer: You spoke with someone who belongs to this organization.

Archive audio, Miriam Weingarten: We heard that Guatemala is a good country, free for religion, good people who like Jews, they like God.

Eliezer: Tell us about her and what she told you about the accusations against Lev Tahor. What do they claim?

Bill: Yes, I spoke with Miriam Weingarten, who is the wife of one of the group’s leaders and who, just when I spoke with her, had less than a week earlier recovered protection, custody of her children, six children. And when I asked her directly if they considered themselves to be a sect and whether it could put its members at risk, they flatly denied it. They say: no, we’re not a sect, we’re just a group of Jews trying to live according to the rules of the Torah. It’s the others who persecute us. We don’t violate anyone’s rights.

Eliezer: And where are the Lev Tahor members now? Because you tell me this whole odyssey of the children, 160 scattered children and adolescents. But what happened to the adults?

Bill: The adults are mostly scattered throughout Guatemala City and a few still in the Lev Tahor community in Oratorio, Santa Rosa, in this small town where they settled. But the majority are scattered throughout Guatemala City, because many are still in legal proceedings for custody of the minors. They’ve been recovering. So they live in houses, in apartments, some rent very precarious places here, others places with more resources, and sometimes, even walking around, you can run into a member. You recognize them easily because they use the strict dress code that is very characteristic, in brown tones and such. I’ve run into them sometimes in the courts, doing some legal procedure regarding the custody of their children, but yes, you find them scattered in different places around the city. Some have indeed left, they’ve returned to their families in the United States, in Canada, or in Israel.

Eliezer: But none of the responsible adults in the community have or have had legal proceedings. In other words, they haven’t been charged?

Bill: There are some members of the community who are indeed being prosecuted. The last time I was able to get an update there were seven, if I’m not mistaken, with active legal proceedings. There have even been extraditions from El Salvador to Guatemala in one case. And yes, there are active criminal proceedings in Guatemala, whether for human trafficking, for transporting minors even across country borders, or for physical abuse of minors, because physical punishments and such are also reported in some cases. And also for sexual abuse—there’s at least one case that’s advancing in that area for sexual abuse by an adult toward a minor. So yes, there are active cases that are still ongoing.

Archive audio, reporter: For a month the authorities carried out surveillance of this sect here in Colombia.

Archive audio, reporter: In Yarumal, a small farming and ranching town in Antioquia with barely 45,000 inhabitants, no one suspected anything.

Eliezer: In late November, Colombian authorities rescued 17 children and adolescents who were under the group’s control.

Archive audio, reporter: It’s the first time that this type of intervention with this sect has been carried out here in Colombia. The minors who are under ICBF custody are in good health. It’s breaking news. At the moment the authorities are investigating.

Eliezer: In Colombia, the sect’s presence has authorities worried because, of course, it’s believed they’re trying to rebuild their community and continue it in that country. Do you think what happened in Guatemala could happen in Colombia?

Bill: I think there’s a certain pattern, which is to seek precisely the margins within states or societies that also don’t quite manage to guarantee the rights of their own populations. And yes, they’re looking for a space where they can somehow recreate what they had for more than ten years in Guatemala. To some extent, a certain impunity for some practices, and that’s why they’re looking for a state and precisely certain margins of society, where they can rebuild without drawing so much attention.

And it also makes you think about how they cross borders and in some cases with minors, with open proceedings, with court restraining orders. So here once again, what you see is the vulnerability of the institutions here, right? Guatemala, Honduras, Colombia—these are places where you can often move without major controls. And of course, if you’re going from north to south they don’t scrutinize you as much, they apply migration controls differently, and of course, the institutions in the region are plagued with corruption, that has to be acknowledged. So something like this is very tangible and can generally give them the conditions to seek refuge in another country, as in this case Colombia.

Eliezer: Do you think they have a chance of disappearing?

Bill: I see it as very difficult. I mean, as long as there are a couple of people with this fervent faith, as long as they keep believing in their doctrine this way and manage to attract support, well, they’ll keep being able to recruit people. And something curious is that, for example, when asking some members how they joined, they all came from traditional Orthodox Jewish families. Even in Miriam’s case, she had a grandfather who had been a rabbi and everything, but she didn’t have a radicalized practice. And what they told me is that they found in this faith what they were looking for. There was something there that nourished them, a need for the absolute, so to speak.

Bill: And as long as that need and that existential void exist in different communities, they’ll have raw material from which to attract people. So I think that also speaks a bit to that need that often exists in our societies, for meaning and community. And that’s what groups like Lev Tahor offer, that sense of community.

Silvia: In early December, the Colombian government expelled nine people from the Lev Tahor sect from the country and handed over the 17 children and adolescents who were with them to United States authorities.

Mariana: This episode was produced by me, Mariana Zúñiga. It was edited by Silvia and Eliezer. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design is by Elías González with his music and Rémy Lozano’s.

We want to thank Bill Barreto for letting us use an excerpt from his podcast Lev Tahor: Guatemala, the Promised Land. You can find it on the website no-ficcion.com.

The rest of El hilo’s team includes Daniela Cruzat, Samantha Proaño, Franklin Villavicencio, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask that you join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to delve deeper into today’s episode, subscribe to our newsletter by going to elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it every Friday.

You can also follow us on our social networks. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook, and Threads. You can find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share the episodes.

Thanks for listening.