Perú

Amazonas

Minería ilegal de oro

Narcotráfico

Locus Map

Monitores

Napo

Nanay

Alto Nanay

Pitunyacu

CINCIA

Mercurio

Esta serie fue producida con el apoyo de Movilizatorio y Alianza Potencia Energética Latam

Las amenazas que enfrentan las comunidades indígenas se van tornando más violentas al cruzar desde la Amazonía ecuatoriana a la peruana. A medida que el río se va haciendo más grande, también aumentan los problemas y la ausencia del Estado. En este episodio de ‘Amazonas adentro’, el periodista Joseph Zárate nos lleva a una zona de la selva peruana donde grupos armados se disputan corredores de narcotráfico y territorios de minería ilegal de oro. Joseph visitó varias comunidades de las cuencas de los ríos Napo, Nanay y Pintuyacu. Allí vio cómo monitores indígenas usan tecnología GPS para vigilar y defender sus territorios de invasiones, plantaciones ilegales, y oportunistas que prometen dinero rápido sin advertir sobre la contaminación y los graves daños a la salud, el medioambiente y el tejido social que causa la minería ilegal.

Créditos:

-

Reportería

Joseph Zárate -

Producción

Silvia Viñas -

Edición

Eliezer Budasoff -

Investigación

Rosa Chávez Yacila -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción digital

Natalia Sánchez Loayza, Helena Sarda, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

Música

Remy Lozano -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

Ilustración

Maira Reina

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Silvia: Hola. Hoy quiero pedirte un favor muy especial. En Radio Ambulante Studios acabamos de lanzar nuestra encuesta anual para aprender sobre ustedes, nuestros oyentes. Con tus respuestas aprendemos sobre tus preferencias, qué funciona y qué no tanto, y cómo podemos servirte mejor. De una encuesta anterior surgió la idea de crear El hilo, por ejemplo. Así que si tienes unos minutos, nos ayudaría un montón conocer tu opinión. Puedes contestar en español o en inglés. Y si nos descubriste hace poco, anímate. Queremos saber de todas las personas que nos escuchan. Visita radioambulante.org/encuesta. Muchas gracias desde ya. De nuevo: radioambulante.org/encuesta .

Esta serie fue producida con el apoyo de Movilizatorio y Alianza Potencia Energética Latam.

Eliezer Budasoff: Para llegar desde la Amazonía ecuatoriana a la peruana, el periodista Joseph Zárate tuvo que viajar en total unas 6 horas en bote. Primero, dentro de Ecuador, desde el Yasuní.

Joseph Zárate: Me fui con la familia de Holmer, este guardaparques que vive en esta comunidad llamada Llanchama, una comunidad kichwa. Fuimos en bote hacia Nuevo Rocafuerte, que es como un centro poblado que está en la frontera entre Ecuador y Perú.

Silvia Viñas: Está a orillas del río Napo, un río que va a ser muy importante en este episodio, uno de los protagonistas, podríamos decir.

Joseph: El Napo nace en la Amazonía del Ecuador y va viajando cientos de kilómetros hasta llegar al Amazonas. Más o menos donde está ubicado Iquitos, que es la capital de la Amazonía peruana. El río Napo es un río histórico para los kichwas. De hecho me contaban algunos dirigentes que en la antigüedad los hombres quichua viajaban en sus pequeños botes a remo a veces hasta un año en busca de la sal, en una zona de la selva peruana donde ahora está ubicado el valle del río Marañón,. Y luego regresaban a su comunidad y bajaban muchos meses río arriba. Así que el Napo es un espacio muy importante para el pueblo kichwa.

Eliezer: De Nuevo Rocafuerte, Joseph viajó otras tres horas en bote hasta llegar al lado peruano. Grabó esta nota de voz.

Joseph, nota de voz: Bueno, son casi las cuatro de la tarde y estoy en Cabo Pantoja. Es el primer centro poblado desde que uno cruza la frontera entre Ecuador y Perú. Hoy en día llegué temprano…

Joseph: Bueno, Cabo Pantoja es una comunidad caracterizada porque tiene ahí una base militar que protege la frontera.

Joseph, nota de voz: Lo que se puede escuchar es el helicóptero, que va volando en círculos, básicamente.

Joseph: Van sobrevolando helicópteros de los militares porque en esa zona hay una presencia muy fuerte de cultivos de hoja de coca. Cultivo ilegal de hoja de coca. Ya han salido varios informes. Por ejemplo, hay un informe de Amazon Watch que ya señala que hay grupos armados presentes en esa zona, ¿no? Y que se disputan los corredores de narcotráfico y territorios de minería ilegal de oro.

Eliezer: En este episodio vamos a explorar lo que encontraste durante tu recorrido por la Amazonía peruana. Pero ¿cuál dirías, en principio, que es la mayor diferencia entre lo que vimos en Ecuador y la situación en Perú?

Joseph: Yo diría que la mayor diferencia que uno puede ver cuando uno pasa de un país a otro, tiene que ver sobre todo con cómo se van agudizando las amenazas que tienen que enfrentar las comunidades indígenas. Uno puede ver, por un lado, el daño terrible de la deforestación. Y por otro lado, se puede ver el impacto de las dragas de minería ilegal de oro. Y también el de las plataformas petroleras. Por ejemplo, cuando hay un derrame de petróleo en la parte del Ecuador, como el río es el mismo, aunque el país sea diferente, todo ese combustible va cayendo hacia el Perú y va contaminando también. Entonces, ciertamente en Ecuador y en Perú las comunidades enfrentan los mismos problemas, pero por lo que yo he podido ver recorriendo estas selvas, conforme el río se va haciendo más grande, los problemas también. Entonces uno puede ver como la defensa del territorio también va sufriendo una degradación.

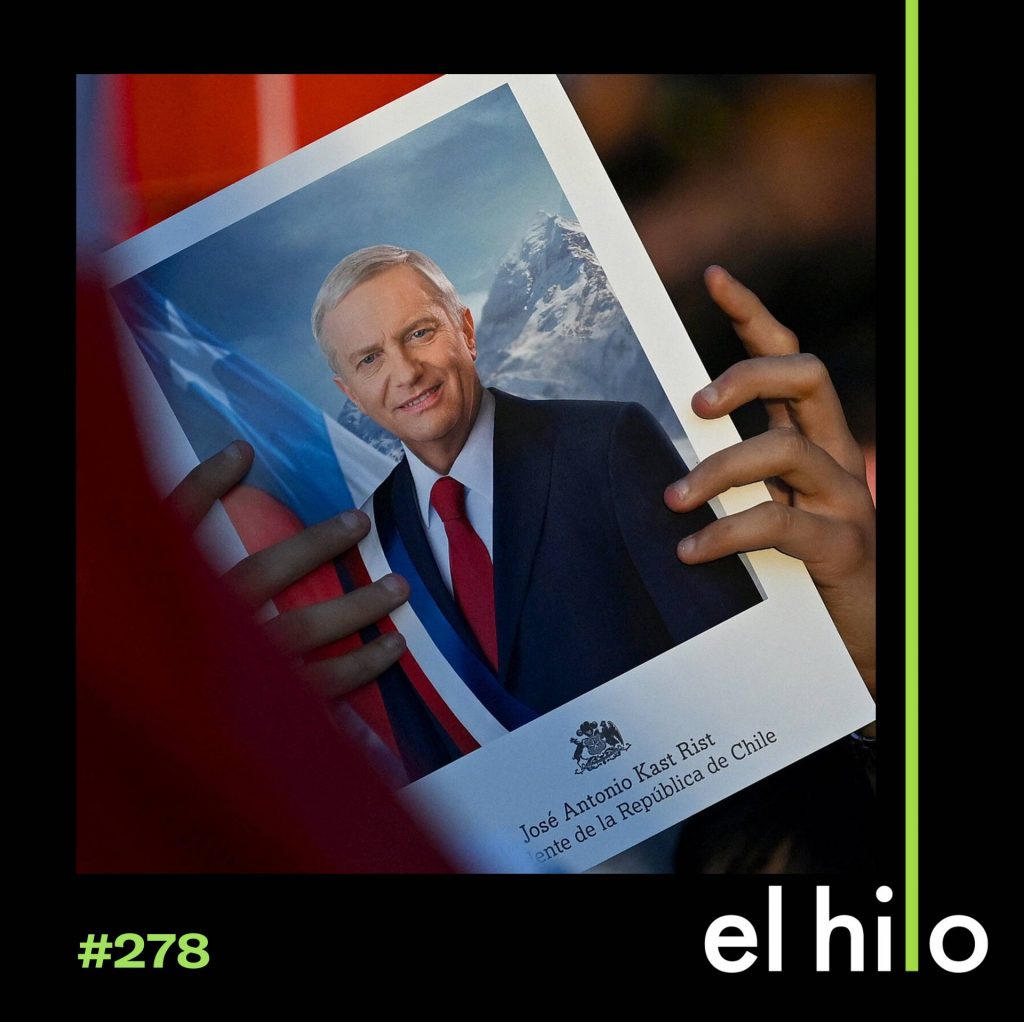

Silvia: Esto es Amazonas adentro, una serie de El hilo, de Radio Ambulante Studios. Episodio 3: Los vigilantes, el río y los oportunistas.

Joseph: Casi al frente de Cabo Pantoja, a unos minutos, está una comunidad que se llama Dos fronteras. Creo que la razón del nombre es evidente. Estamos ahí en la zona fronteriza.

Maricruz Canelos: Nos encontramos en la comunidad nativa Dos Fronteras caminando con los compañeros monitores.

Joseph: Y allí conocí a una joven de 33 años que se llama Maricruz Canelos, que es monitora ambiental de la comunidad Dos Fronteras. Y también conocí a Humberto Ramos, que es el presidente de la comunidad.

Humberto Ramos: Nosotros hacemos el trabajo de conservar nuestro territorio como peruanos que somos.

Joseph: Y también vicepresidente de Orkiwan. Orkiwan es la organización Kichwaruna Wangurina del Alto Napo. Es la organización que reúne a las dirigencias de las comunidades que están entre Cabo Pantoja y más o menos Santa Clotilde, que es otra comunidad que está a varias horas río abajo. Y cuando llegué, pues, lo primero que yo vi fue una inundación.

Humberto: La naturaleza nos está inundando y esta creciente viene y perjudica nuestros sembríos, porque nuestro territorio es, toda la mayoría es terreno bajo y la creciente nos inunda.

Maricruz: Acá todos los años el mes de julio crece y nos deja este inundado feo el campo, ¿no?

Joseph: Todos los años hay inundación, todos los años crece el río. Pero ellos me decían que nunca había crecido tanto, ¿no? Eso es lo que más les preocupaba.

Joseph: ¿Y a qué cree usted que se deba que ocurren estas cosas? ¿Por qué ocurren estas cosas?

Humberto: Por el cambio climático que hay por el fenómeno del niño y todo eso que se viene sabiendo y son las cosas que manda la naturaleza y no tenemos cómo controlarla de verdad.

Joseph: En la última década, la Amazonía peruana, sobre todo esa parte del Perú, viene enfrentando un incremento de estos cambios climáticos. Entonces claro, antes en la época de sequía o de vaciante, que le llaman, y en la época de lluvias éramos como muy marcado ¿no? En cada año. Pero ahora esto ya no se puede definir. O sea, ya la gente no sabe muy bien cuándo va a empezar la sequía, cuándo va a empezar la época de lluvias y cuánto va a durar.

Joseph: Una cosa que me comentaba es que cuando el agua viene del Ecuador también hay mucha contaminación.

Humberto: Sí, exactamente. Y eso es lo que más le daña al plátano.

Joseph: Si ocurre un derrame de petróleo, ¿verdad? En las plataformas que están cerca del Yasuní, por supuesto que como el río siempre está bajando hacia el Perú, esta contaminación afecta inmediatamente a la comunidad de Dos Fronteras y a las demás.

Humberto: Contamina todo y lo mata y ya no se puede consumir porque le sacamos la yuca y ya sale contaminada con el petróleo. Ya no se puede comer y eso es preocupante.

Joseph: Claro, el agua también.

Humberto: El agua no se puede tomar porque está contaminada. Nuestros niños sufren con la anemia y todo eso, es bien preocupante. Y como a veces la autoridad competente no viene por acá y piensa que estamos viviendo feliz, tranquilo, cuando no es así.

Joseph: Sí hay minería ilegal, también. El uso del mercurio, como vamos a ver más adelante, esa contaminación, también afecta a la comunidad de Dos Fronteras. Ciertamente, también ha habido una serie de impactos causados por la invasión de terrenos, por ejemplo. Comunidades que están del lado ecuatoriano y que invaden el territorio de la comunidad de Dos Fronteras. Entonces, por más que los militares ejerzan la seguridad, vigilen el territorio, si hay una afectación de un lado, va a afectar el otro. El agua fluye y corre y es imparable. Entonces creo que lo que vi en Dos Fronteras es un ejemplo de eso. De esa causa-efecto inmediata en lo que ocurre en esa zona de la Amazonía.

Eliezer: En un momento nos mandaste una nota de voz…

Joseph, nota de voz: Acabamos de llegar a la comunidad de Santa María de Angoteros. Hemos más o menos navegado unas tres horas para llegar hasta esta comunidad…

Eliezer: Donde decías que iban a ver el monitoreo de personas que usan GPS para vigilar puntos de riesgo.

Joseph, nota de voz: De ciertas amenazas, utilizando pues, tecnología GPS, utilizando aplicaciones para poder vigilar algunos puntos de riesgo.

Eliezer: ¿A qué te referías con eso?

Joseph: Es bien interesante, ¿no? Yo conocí a Jaime Cárdenas, él es coordinador regional de los programas de la Fundación Rainforest US.

Jaime Cárdenas: Ya llevo trabajando con ellos cerca de ocho años. Soy ingeniero en Ecología de Bosques Tropicales. Tengo 33 años de edad.

Joseph: Muy, muy capo, por la experiencia que él tiene recorriendo, digamos, esa zona.

Jaime: El monitoreo consiste en que las comunidades hoy en día puedan adaptar herramientas tecnológicas, porque ancestralmente ellos siguen cuidando sus territorios, pero adicionalmente, pues hoy en día se suma el tema de la tecnología.

Joseph: Me contaba Jaime que ellos adaptaron una aplicación que normalmente la utilizan, pues, las personas que escalan montañas, que hacen trekking ¿no? Que se llama Locus Map. Entonces la adaptaron para que estos monitores ambientales indígenas puedan utilizarlas sin necesidad, digamos, de saber demasiado de tecnología, ¿no? Entonces, de una manera más intuitiva. Y por supuesto, también pueden usar esta aplicación sin necesidad de estar conectados a internet. ¿Entonces, qué hacen con esta aplicación?

Jaime: Se pueden ubicar en tiempo real por donde ellos están caminando. hacer una vigilancia, una caminata, un patrullaje por el territorio y pues, está la alerta de las amenazas que puedan existir dentro de estas comunidades.

Joseph: Ellos pueden identificar a través de GPS los puntos de riesgo. ¿A qué llaman puntos de riesgo? Puede ser, por ejemplo, desde un árbol que se ha caído sobre el camino. O de repente una plantación ilegal, ¿verdad? De coca. O podría ser también la presencia de una draga de minería ilegal. Entonces, a través de esta aplicación en el mapa satelital, ellos pueden identificar a qué distancia está de la comunidad. Pueden dibujar sobre el mapa el recorrido que hacen y de esa manera pueden ir vigilando, ¿no? Y después los que capacitan en Rainforest van a la comunidad y recogen esa información para sistematizarla y poder, de alguna manera, hacer como una especie de monitoreo mucho más sofisticado, ¿no? del territorio.

Silvia: Si están usando tecnología, me imagino que muchos son jóvenes.

Joseph: Sí, la mayoría son jóvenes. Yo te contaba hace un momento, Maricruz, por ejemplo, que tiene 33 años. Y es bien interesante por la figura de ella, ¿no? Porque…

Jaime: Antes eran… Todos eran hombres. Todos eran hombres. Todos. Y poco a poco se ha ido viendo, diciendo que… Nosotros también en las asambleas les motivamos, les incentivamos de que esto no solo es un trabajo que pueden desarrollar los hombres, sino que también las mujeres tienen las capacidades para que puedan desarrollar.

Joseph: No las dejaban.

Jaime: No les dejaban. O sea, muchas veces el machismo es muy fuerte en esta zona.

Joseph: Entonces, que haya una monitora y que hayan, digamos, la presencia de las mujeres liderando ese trabajo, me parece que es muy importante, ¿no? De hecho, yo cuando hablaba con los compañeros de Rainforest, ellos me contaban que este programa de monitoreo forestal que ellos tienen ¿no? me contaban que desde el lanzamiento de este programa, el número de mujeres Kichwas, Ticuna, Matsés ¿no? Que son otros pueblos originarios, ha crecido de… Empezaron con tres y ahora hay 34. Hay monitoras, capacitadoras, coordinadoras de proyecto.

Maricruz: También soy mujer líder, tesorera del apu y tengo más cargos.

Joseph: ¿Cómo cuáles? Por ejemplo

Maricruz: Promotora de salud, también.

Joseph: Eso es una señal, ¿verdad? Del empoderamiento de estas monitoras.

Joseph, nota de voz: Bueno, son las seis de la mañana del 16 de julio. Ahora estamos en Santa Clotilde. Es un centro poblado que está cada vez más cerca de Iquitos.

Joseph: Una vez que nosotros hicimos este primer recorrido, por esta parte, la parte alta del Napo peruano, digamos, llegamos a Santa Clotilde que también está a orillas del río Napo. Que en Santa Clotilde es donde termina la jurisdicción, digamos, de Orkiwan. Que han podido ir sedimentando, ir consolidando la unión entre ellos, la organización, para impedir que, por ejemplo, las dragas de minería ilegal de oro sigan afectando su territorio. A partir de Santa Clotilde, hasta más o menos Mazán o Iquitos, que es la zona más urbanizada, ya le pertenece a otra federación, que tiene otras comunidades. Entonces esta otra federación, las comunidades también son kichwas, pero por lo que me contaban los pobladores la organización es un poquito más débil, ¿no? ¿Por qué? Porque ya no hay solamente kichwas allá, sino que hay gente mestiza, hay gente de otros lados, entonces es un poco más complicada ahí la organización.

Joseph, nota de voz: El día de hoy vamos a recorrer la última comunidad que se llama Vista Hermosa, que está a orillas del río Tambor Yacu, que está como a tres horas…

Joseph, nota de voz: Hay que caminar con cuidado…

Joseph: Entonces Vista Hermosa es una comunidad kichwa.

Joseph: Y allí pude conocer también a una monitora que era la presidenta de la comunidad de Vista Hermosa que se llama Silda.

Silda Dahua: Mi nombre es Silda Dahua Sandoval Depapa. Tengo 49 años. Soy apu de la comunidad nativa de Vista Hermosa.

Joseph: Ella, junto con otras dos compañeras, van recorriendo el territorio, ¿verdad? De acuerdo a como le va señalando la aplicación.

Silda: Aquí vamos a referenciar este muro, que estamos haciendo el trabajo.

Joseph: Abren la aplicación, van apareciendo ciertos puntos rojos. Cada punto rojo es un punto de riesgo, ¿no? Entonces ellas tienen que ir hasta el punto rojo a averiguar qué tipo de riesgo es. Fuimos recorriendo una zona de su comunidad para poder mirar uno de esos puntos.

Silda: Vamos a describir aquí.

Joseph: Entonces ahí marcas el punto que has venido a vigilar. Le pones una descripción, ¿verdad?

Silda: Haciendo…

Joseph: Monitoreo. ¿no?

Silda: ¿Cómo te pongo? ¿Cómo te digo?

Joseph: Con el periodista.

Silda: Ya, con el….

Joseph: Periodista.

Joseph: Estuvimos caminando como 40 minutos. Me estuvo contando la serie de problemáticas que hay en su comunidad. Una de las más graves, es que hace algunos años estaban en la necesidad de obtener el título legal de su territorio.

En el Perú, desgraciadamente, hay muchas comunidades que no tienen el título legal de su territorio, o sea, viven ahí desde hace mucho tiempo, pero no tienen el papel legal. Y para poder sacar el título de propiedad de la comunidad necesitas dinero, un dinero que muchas veces ellos no tienen. Entonces, lo que me contaba Silda era de que llegó un habilitador, un empresario maderero, digamos.

Silda: Hizo la reunión diciendo que él va a trabajar sacando la madera y él quiere sacar el título de la comunidad.

Joseph: Ofreciéndoles ayudarles a sacar el título de su propiedad a cambio de sacar madera de su propia comunidad. Es decir, les decía: tú me das permiso a poder sacar madera de tu comunidad, de tu territorio, y yo pago los gastos para poder titular la comunidad. Entonces ellos dijeron, bueno, perfecto. Es una con otra, ¿no? Un win-win, digamos, como se dice. ¿Pero qué pasó? Se fue el habilitador, pasó el tiempo y ellos se preguntaban: ¿oye, pero no ha venido a sacar madera?

Silda: Solamente quería hacer como dicen, hay una palabra que se dice: hacer la lavada de madera. Dicen que está sacando de aquí del territorio de Vista Hermosa, pero no ha sacado ni una vez de aquí.

Joseph: Entonces, en un momento las autoridades forestales fueron a la comunidad a verificar si este empresario había sacado o no madera. Y resulta que no había sacado madera de ahí, sino de otro lado. Pero el habilitador había usado el permiso firmado de la comunidad, diciendo que habían sacado madera de su comunidad. Entonces, claro, a quien multaron fue a la comunidad y no al habilitador.

Entonces, cuando la comunidad de Vista Hermosa se dio cuenta de todo esto, más o menos por el año 2018, Vista Hermosa debía a la autoridad forestal un monto que superaba los dos millones de soles. Y dos millones de soles, en multas, es poco más de medio millón de dólares. Es muchísimo dinero. Básicamente habían sido estafados.

Lo más preocupante de eso es que esta estafa ocurrió durante tres gestiones de apus diferentes, de la comunidad. Por supuesto, después de esta experiencia los han expulsado, o sea ya no dejan entrar a estas personas. Porque claro, ok, sufrieron esta estafa, este problema que ahora están resolviendo a través de la conservación. Pero ya no van a ser engañadas de nuevo. Conocen las leyes, pueden transmitir el conocimiento del cuidado del territorio, tienen el apoyo de estas organizaciones. Pero lo que no veo es el apoyo del Estado peruano. Eso es lo que no veo. Muchas veces la responsabilidad del cuidado del territorio recae, o suele recaer, en las comunidades indígenas. Ah, las comunidades indígenas son los defensores de la Amazonía, y eso a veces hace olvidar que quienes deben defender esos territorios, sobre todo, son los Estados, que para eso fueron creados. Pero qué pasa, que los Estados los dejan indefensos.

Silvia: Hacemos una pausa y volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta.

Plinio: ¿Cómo estás, Roque? ¿Cómo están los monitores?

Joseph: Después de estar con Silda. dejamos la cuenca del río Tambo Yaku. Seguimos bajando, ¿verdad? Y en la última comunidad que visitamos ese día, ya por la tarde, llegamos a Nuevo San Roque.

Plinio: ¿Los monitores?

Monitor: Aquí estamos.

Plinio: Necesito los celulares para revisar la data para poder pagar.

Monitor: Sí.

Joseph: Fue bien interesante y también preocupante lo que encontramos, ¿no? Nosotros estábamos yendo a dejar donaciones, a dejar unas herramientas, y pues fuimos a buscar al apu de la comunidad. Y el apu pues salió de una casa con la música a todo volumen, y salió así como tambaleándose, y al toque nos dimos cuenta que se encontraba, digamos, en un seguro estado de ebriedad, ¿no? Por toda la chicha que había tomado.

Plinio: ¿Les ha ofrecido algo el minero o no?

Apu: No.

Joseph: Me acuerdo mucho que uno de los compañeros de Rainforest US, Plinio Pizango, jefe de transferencia tecnológica de la fundación, y que también lidera los programas de capacitación a los monitores en ese territorio, le dijo al apu, medio en broma, medio enserio: Oye, y me han contado que ahora te has vuelto minero. Y el apu le dijo: No, no, inge, ¡no! Nosotros hemos expulsado a los mineros. Así le dijo primero, pero luego ya el apu comenzó a sincerarse.

Apu: Mira, nosotros por necesidad estaba un barquito, estaba acá.

Plinio: Ya, ya.

Apu: Que yo quisiera decir en la realidad, Ingeniero.

Plinio: Claro, o sea, por eso, por eso he venido a conversar con ustedes, porque habían visto un barquito aquí estacionado.

Joseph: Y nos contó una historia bien inquietante. Él nos contó…

Apu: Era para festejar nuestro aniversario.

Plinio. Ya…

Joseph: De que el aniversario de la comunidad había ocurrido hace algunas semanas y que ellos no tenían dinero para poder comprar unos chanchos para poder hacer la comida de la comunidad ¿no? Invitar… Porque siempre en la cultura kichwa, pues, cuando hay un aniversario de una comunidad, pues vienen todas las otras comunidades a tu casa, a tu territorio para celebrar, con chicha y con carne y con muchas cosas. Entonces cuando llegó una draga de minería ilegal de oro le dijo bueno, yo les doy 500 soles y ustedes me dejan estar acá unas semanitas, digamos, ¿no? Y bueno, aceptaron el dinero.

Plinio: Ustedes siempre han trabajado muy bien, protegiendo el territorio, no dejando entrar a los madereros, no dejando entrar a los mineros ilegales. Ustedes saben que ese señor comete un delito, ¿no? Sí. Y mañana más tarde, cuando a él lo chapan, él va a decir: no he sido yo. Va a decir Estoy acá con el permiso del apu. ¿Y cómo vas a quedar tú?

Joseph: Y dejaron estar ahí la draga durante casi un mes. Hasta que ellos dijeron: bueno, ya van a venir los ingenieros de Rainforest, entonces es buena hora de expulsarlo, ¿no? Y los expulsaron. Pero bueno, o sea, cuando yo los escuché y explicaban todo esto, intentaba yo entender también la circunstancia en la que viven. Es ciertamente, nuevo San Roque, como muchas de las otras comunidades que visité, que viven pues en un estado claramente de pobreza, ¿no? de pobreza muy, muy honda también.

Me contaban que no había ahí tampoco como una posta médica, no había servicios básicos y el trabajo en la chacra se había afectado por las inundaciones también. Me quedé pensando en verdad cómo la propia necesidad empuja o te empuja en ciertas circunstancias de tu vida a hacer cosas que tal vez no quieres hacer. Hacer cosas que tal vez van en contra de tu propia integridad, de tu propia salud, ¿no? Y tal vez cuando ya tú las comienzas a hacer y sostienes muchos años esa actividad, de pronto te das cuenta que ya es muy tarde para ir hacia atrás. Esto que estaba pasando en Nuevo San Roque fue el inicio también de lo que viene ocurriendo en otras zonas de la Amazonía peruana, ¿no? Solamente que ahora en esas zonas ya la minería ilegal de oro, pues lo ha tomado casi todo, ¿no? Empezaron así como Nuevo San Roque, dejando entrar una, dos dragas un tiempo, pero ahora ya les cuesta mucho poder recuperar su propio territorio.

Hoy en día, pues, estamos hablando ya de mafias en un área de conservación regional del Alto Nanay. El Alto Nanay es un distrito, es un distrito que está atravesado por tres ríos: el río Nanay, el río Pintuyacu y el río Chambira. Entonces, el río que está más tomado por la minería ilegal de oro es el río Nanay. Entonces, yo viajé hasta la parte alta del río.

Joseph: Para que ustedes tengan una idea y puedan hacerse la imagen en la mente, ¿no? En la parte baja del río Nanay, que es la que está más cercana a la ciudad de Iquitos, hay una zona de playas, que por lo menos unos cuatro meses al año, cuando hay vaciante, cuando hay, cuando el río baja, digamos, se forman unas playas hermosas de arena blanca, ¿no? Yo fui de hecho a una de ellas que se llama Playa Muyuna, donde se hacen conciertos, exposiciones de cine, etcétera. Parece, pues, una playa así como del Caribe, básicamente. Con una música muy alta, cumbias, etcétera La gente divirtiéndose, comiendo.

Y yo pensaba cuando estaba ahí, que la gente no tiene ni idea de lo que está ocurriendo en la parte alta de ese mismo río. Están estas mafias, están estas dragas, que son unas pequeñas embarcaciones hechas de madera, muchas veces, que, digamos succionan a través de unas mangueras el lecho del río van extrayendo la tierra y van filtrándola para poder capturar las partículas de oro. Y con el mercurio, que es un metal tóxico, un metal líquido, lo que hacen es esas partículas, pequeñas partículas de oro, las van amalgamando, las van juntando, y una vez que ya la juntan, hierven esa mezcla, esa amalgama para que el mercurio se evapore y solamente quede el oro junto, el oro amalgamado.

Claudia Vega: Todos los mineros llegan así como: el Estado no te da nada, eso te va a dar dinero rápido. Lo que no explican los mineros es que después que terminen de sacar el oro, el bosque está contaminado, el agua está contaminada y el costo en la salud de la población es bien alto.

Joseph: Para poder entender mejor esto, esta afectación, yo entrevisté a Claudia Vega, que es coordinadora del programa de mercurio de CINCIA, que es una ONG. CINCIA significa Centro de Innovación Científica Amazónica. Ella es una Científica salvadoreña

Claudia: Tengo 47 años y tengo más o menos un poco más de 15 años de estar estudiando el mercurio en la Amazonia. Comencé en la brasileña y ahorita desde 2017 estoy aquí en la Amazonía peruana.

Joseph: Entonces, los científicos de CINCIA, en colaboración con la Sociedad Zoológica de Frankfurt Perú, realizaron un estudio en seis comunidades indígenas en las cuencas de los ríos Nanay y Pintuyacu, que son las cuencas donde yo estuve haciendo trabajo de campo. Y este estudio se concentró en documentar y evaluar el nivel de contaminación por mercurio que hay en las personas y también los peces, digamos, que son la base de la dieta de estas comunidades.

Claudia Vega: La principal vía de exposición de mercurio en el ser humano es la ingestión de pescado contaminado. Si la madre come peces contaminados o peces con niveles altos, el feto está recibiendo eso, y aunque la madre no muestre ningún síntoma, el feto puede, el bebé puede nacer con síntomas visibles y síntomas que son irreversibles.

Joseph: ¿Como cuáles?

Claudia: Pueden tener síntomas silenciosos, como dificultad de aprendizaje, dificultad de habla, dificultad de memoria.

Joseph: Los resultados del estudio de CINCIA, por supuesto son preocupantes. De las 273 muestras de cabello que se tomaron de personas que viven en estas seis comunidades del Alto Nanay, estamos hablando de Diamante Azul, Santa María de Nanay, entre otras, el 79% de estas muestras, es decir 215 personas, presentaban niveles de mercurio por encima de los límites máximos que establece la Organización Mundial de la Salud. Y por otro lado, cuando hablamos de la evaluación de los peces, los resultados también son preocupantes. Los investigadores de CINCIA recolectaron unos 284 individuos, peces, de 43 especies, en cochas y en zonas distintas del río Nanay. De esta muestra, el 14% superó el valor recomendado para consumo humano de mercurio según la OMS. Entonces estamos frente a una clara contaminación por este metal tóxico.

Claudia: ¿Qué es lo que pasa en la región amazónica? Es donde la actividad minera se da sin control y no solo se da en Perú, se da en Brasil, se da en Colombia, se da en Ecuador. Siento que el Nanay como es… Bueno, tiene uno, que la minería está está aumentando. Entonces de nuevo nos da una señal de alarma antes que el desastre pase. Y es algo que se puede evitar.

Joseph: ¿Si no se hace nada?

Claudia: Podemos tener un desastre.

Joseph: ¿Como qué, por ejemplo?

Claudia: Las poblaciones van a seguir consumiendo peces y si yo contamino esos peces, las poblaciones van a verse expuestos a niveles altos de mercurio. ¿Y eso a quién afecta? Principalmente a los niños. Estamos comprometiendo a las nuevas generaciones.

Edgar Isuriza: La minería ilegal nos afecta bastante a nuestra salud, como por ejemplo, aquí tenemos un niño ya, una niña que ha nacido ya disforme, sin manitos y sin bracitos, sin sus piernitas.

Joseph: Edgar Insuriza es expresidente comunal de Santa María del Nanay, una comunidad campesina.

Edgar: Retrocediendo años atrás, nosotros teníamos el pescado en abundancia. Pero cuando ya ha entrado esta minería, uno, que los peces están contaminados y cuando están contaminados no nos compran, no nos consumen.

Joseph: Él también fue analizado junto con su familia, y pues el resultado de ese estudio arrojó que ellos también tienen altos índices de mercurio en sus cuerpos. Y me hablaba de la preocupación permanente que él tiene sobre eso. Me hablaba también de cómo cuando él era autoridad, ¿no? Presidente comunal de Santa María, fue muy frontal frente a la amenaza de la minería, organizó a los dirigentes, a las comunidades, para cerrar en un momento el río e impedir que sigan llegando lanchas que traen, pues, combustible para poder sostener las dragas ilegales en el Alto Nanay. Y que por ese trabajo, ese trabajo frontal, él, pues, ha sido amenazado, ha sido vigilado por estos mafiosos.

Edgar: Ahí en ese lugar de áreas de conservación, ahí está cimentado las… Hablábamos de 75 dragas, hoy ya tenemos información que son 120 dragas.

Joseph: Edgar me comentó también. Bueno, en realidad, todos, ¿no?. Y uno decía algo que ya se sabe, cuando tú vas hablando, por ejemplo, con, no solamente con los dirigentes del Alto Nanay, sino que hablas, por ejemplo, con gente de la Fiscalía, hablas con gente de las ONGs que trabajan en esa zona. Cuando revisas las notas periodísticas sobre lo que viene pasando en ese lugar, todas mencionan a Alvarenga.

Edgar: Es una comunidad nativa que así, siendo exacto unas aproximadamente de 12 familias, oriundos de ahí. Pero ya que se han ido a meterse por el tema de minería, pues se hablaba de 30 familias. Colombianos, brasileros, venezolanos.

Joseph: En Alvarenga, pues, según lo que me cuentan, hay una serie de grupos que muchas veces han entrado hasta esa zona del alto Nanay diciendo que son turistas, ¿no? Pero en verdad, turistas no son, sino son personas que trabajan en minería ilegal y que, pues no hay, no se ha podido ejercer un control en ese territorio, porque muchos de estos grupos están armados.

Me hablaban también de la presencia de algunos integrantes de disidencias de las FARC, por ejemplo, hay una especie como de territorio tomado por la minería ilegal. Y lo que me decían los dirigentes es que no me recomendaban ir hasta ahí, porque a veces ni las ONGs llegan, ni siquiera se atreve a llegar ahí la Fiscalía. Han ido hasta ahí, pero tampoco es que vayan muy seguido precisamente por esto, ¿no? Por esta cuestión de indefensión.

Edgar: La Policía, la Marina, la fiscalía. Se han ido a hacer los operativos. Revientan 5, 6, 7 dragas mucho. Hace un mes que han reventado 20 dragas, pero ahorita hay 40.

Joseph: Es una zona ciertamente muy peligrosa. Yo pude ir hasta cierto punto ¿no? Yo llegué hasta una comunidad que se llama Puca Urco. Y yo vi, hice fotos y demás de un par de dragas que estaban trabajando ahí frente a Puca Urco. Y lo que más me sorprendió es que estaban haciendo su trabajo a plena luz del día y sin ningún tipo de problema. O sea, como si estuvieran seguros de que no va a venir nadie a reventarles la draga. Ningún militar. Ningún policía.

Joseph: Pude ver también… Nos metimos a algunos bares, a hablar con la gente. ¿No? Vimos ahí mucha presencia también de jovencitas colombianas, venezolanas, que según lo que me cuentan los pobladores se dedican a la prostitución. Muchos de los jóvenes que trabajan en la minería ilegal de oro gastan su dinero en eso. Por lo que me contaban, por ejemplo, para pasar una noche con una de ellas, uno puede gastar entre uno y dos gramos de oro.

Joseph: Pude evidenciar eso, obviamente tratando de mantener un perfil bajo. Dormimos, pasamos la noche en Puca Urco, pero en la lancha. Entonces al día siguiente, cuando yo me levanté y fui a buscar algo de comer, al bajar de la lancha se me acercó uno de los dragueros, y me preguntó de una manera muy, muy agresiva, que qué hacía ahí, que si yo era periodista, qué cosa estaba haciendo ahí, que no esté preguntando, que no me metiera en problemas. De una manera muy amenazante. Me estaba amenazando, ciertamente. Entonces, nos tuvimos que ir unas horas después de ese lugar, porque, pues, era muy peligroso. Entonces, cuando ya llegamos a Santa María del Nanay, ya bajando en lancha pública, pude hablar con uno de los dirigentes que entrevisté.

Joseph: No he estado solo yo.

Dirigente: No te digo que son bien…

Joseph: Son… es que sí hubo uno que me amenazó.

Joseph: Uno de los dirigentes que era amenazado me dijo que habían recibido la noticia, una llamada desde Iquitos de un personaje llamado Papillón, que es un capo de la minería de oro, que había dado el aviso que había un periodista…

Que tiene gafas negras, que siempre está vestido de negro, que tiene la descripción de mi persona, básicamente, que que estaba haciendo preguntas y que estaba viajando hacia las comunidades y que apenas llegar a una de ellas, pues me detuvieran y me quitaran mis cosas. Para que impidieran que yo hiciera el trabajo,

Joseph: Te agradezco por avisarme igual. Pero ellos piensan que yo recién estoy yendo…

Dirigente: Ahorita ya saben todo….

Joseph: Pero bueno, afortunadamente yo pude salir de ese lugar antes de que eso ocurriera. Y eso pues te da una idea, ¿no? De lo peligroso, de lo inquietante que es ese lugar. Cuando yo tuve la oportunidad también de hablar con fuentes de la Fiscalía, de la Fiscalía Medioambiental de Loreto, ahí en Iquitos, me hablaban también del casi nulo presupuesto que tienen para hacer su trabajo. Me acuerdo muy bien que uno de ellos me mostraba el chaleco antibalas que tiene y me decía o sea, ese chaleco es una donación. O sea, ni siquiera es que les compran el chaleco, ¿no? Que para poder utilizar el helicóptero de la Marina, por ejemplo, le tienen que pedir de favor a la marina un par de horas para usar el helicóptero. O sea, no tienen dinero. Y luego también pude ver algunos videos que ellos han grabado de sus intervenciones.

Agentes fiscalía: ¡¿Para qué vienen carajo?!

Joseph: Y uno cuando ve los videos y escucha los audios. Cómo se enfrentan, con armas, con disparos.

Agentes fiscalía: ¡Retírate!

Joseph: Es muy inquietante, muy preocupante, ¿no? Lo que viene pasando ahí y todo lo que los dirigentes tienen que pasar, además de la contaminación que hemos hablado.

Agentes fiscalía: ¡Estás cometiendo un delito!

Eliezer: Hacemos una última pausa y volvemos.

Joseph: O sea, acá han hecho minería.

Mercelina Angulo: Sí, aquí han hecho minería, hasta allá era la playa, pero como hicieron minería, esto se huequeó, o sea…

Joseph: Se ha destruido.

Marcelina: Se ha destruido todo y se quedó así como está.

Silvia: Antes de llegar a la Triple Frontera, donde convergen Perú, Colombia y Brasil, Joseph visitó una última zona del Alto Nanay.

Joseph: Que es la zona donde está el río Pintuyacu. Una zona muy cercana, porque el río Pintuyacu es un río cuyas aguas desembocan en el río Nanay. Son ríos que están unidos.

Marcelina: Nosotros en la realidad tenemos bastantes minerales. ¿Pero de qué sirve trabajar un mineral si realmente nos afecta directamente como humano?

Joseph: Nos encontramos con Marcelina, que fue a recogernos en su bote a motor.

Marcelina: Mi nombre es Marcelina Angulo Chota. Soy la vicepresidenta del Comité de Gestión del Área de Conservación Regional.

Joseph: Una mujer muy admirable, sobre todo por las historias que me contó. Es una mujer, también, una dirigente que vive amenazada.

Marcelina: “Oye ─me dice─, así como me cagaste te voy a cagar yo. Me quitaste todo, que sé dónde vives. Voy a comenzar donde más te duela. Te va a doler bastante porque los hijos son los que valen, pero si no, tú no sigues haciendo esto. Seguiré desde el más chico hasta el último que eres tú”.

Joseph: Marcelina tiene 41 años y es madre también. Tiene 4 hijos.

Joseph: ¿Cuánta gente más o menos vive acá en Saboya?

Marcelina: Aquí en Saboya están 35 familias.

Joseph: Y esa es la comunidad más grande, me dicen.

Marcelina: Esta es la comunidad más grandecita que hay a nivel de los seis hermanos.

Joseph: Vive en una comunidad que se llama Seis hermanos. Se llama Seis hermanos porque está compuesta de seis anexos, que cada una tiene su nombre. Y el anexo principal de la comunidad Seis hermanos es una que se llama Saboya, donde, pues, Marcelina pasó su niñez, y mientras caminábamos me iba contando el trabajo que vienen haciendo de vigilancia. Ella me contaba que hace algún tiempo en esa zona del Pintuyacu había dragas de minería ilegal.

Marcelina: Lo que hicimos es organizarnos. Hemos sacado, fueron en botes a sacar cada uno. Algunos han llevado sus armas y algunos se fueron preparados también con palos, si pudiera pasar algo. A conversar con ellos directamente y les hemos dado solamente unas horas para que ellos se retiren, y verdad, se han retirado.

Joseph: Gracias a la organización de las de los anexos de Seis hermanos, ¿no? Los seis hermanos se juntaron, digamos, para poder expulsar estas dragas, haciendo grupos de vigilancia.

Marcelina: No teníamos contacto ni con la policía, ni con la Marina, ni con el fiscal. Así hemos hecho nuestro trabajo, solos, organizados, como comunidad.

Joseph: El gobierno regional o las autoridades, pues, no las apoyan. Me mostraba en un momento un bote todo oxidado, malogrado y que no tenía el motor funcionando, pues, porque no tenían dinero para mandarlo a arreglar. hay una necesidad de recursos para poder, digamos, hacer esa defensa.

Marcelina: ¿Sabes qué es lo que tienen miedo los dragueros? A que nosotros nos organicemos como comunidad. La comunidad tiene más fuerza que usted venga de otro lugar y quiera sacarles porque no conoce la realidad. Por qué ha aumentado y por qué sigue como está, ees porque las autoridades mismas se han cohibido tanto del centro, del medio y distrital.

Joseph: Me decía Marcelina con preocupación era pues, que claro, ellos se han organizado, han hecho lo posible para expulsar estas dragas. Pero pues la necesidad es tan grande que ya algunos dirigentes, según me comentaba Marcelina, han comenzado a pensar si acaso no sería buena idea para ellos dejar entrar a las dragas. Y ciertamente, eso de nuevo nos pone en una situación complicada, ¿no? Que uno en términos humanos puede comprenderlo también. Es decir, una cosa que me decía Marcelina es, claro, nosotros venimos defendiendo este territorio sin dinero, con nuestros propios recursos, con nuestra propia energía, poniendo en riesgo nuestra vida y a nuestras familias. Pero por otro lado está esta oferta ¿no? Esta oferta de poder tener un ingreso, de poder tener una economía. Entonces nosotros no sabemos cuánto tiempo más vamos a resistir. Ella está convencida, por supuesto, que va a seguir adelante a pesar de las amenazas. Pero, pues, no sabe qué puede ocurrir después.

Marcelina: A pesar de todas esas cosas, sigo ahí o no me voy a rendir me voy a retirar tal vez cuando me maten, peor si no hacen nada por mí. Disculpa, es que tengo, tengo una impotencia grande, porque este reclamo que venimos haciendo no es de ahora. Este reclamo es de mucho tiempo. No hay uno más que tú vas a entrevistar en la zona del Pintuyacu, no hay uno más que le vas a escuchar como yo hablo, como yo lucho en mi comunidad. Lo hago de todo corazón por todos los niños que tenemos, por todas nuestras poblaciones que tenemos acá y por, también, salvar esas vidas que están más allá que la ciudad de Iquitos.

Eliezer: En el próximo episodio…

María Fernanda: No podemos hacernos los de la vista gorda frente a una realidad que está llegando a todos los territorios indígenas.

Andrés: Es muy irónico que un proyecto que se está realizando, que está totalmente activo en el mercado ni siquiera es conocido por la gran mayoría de los habitantes de ese resguardo que lo albergan.

Reinaldo: 100 años. Imagínate. Diez décadas íbamos a estar nosotros garantizando ese bono de carbono a esas empresas.

Eliezer: Este episodio lo produjo Silvia con la reportería de Joseph y la investigación de Rosa Chávez Yacila. Lo edité yo. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido es de Elías González con música de Remy Lozano.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Soy Eliezer Budasoff. Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Silvia: Hello. Today I want to ask you for a very special favor. At Radio Ambulante Studios, we’ve just launched our annual survey to learn about you, our listeners. With your responses, we learn about your preferences, what works and what doesn’t, and how we can serve you better. A previous survey, for example, led to the creation of El Hilo. So if you have a few minutes, it would help us tremendously to know your opinion. You can answer in Spanish or English. And if you’ve just discovered us, please go ahead. We want to hear from everyone who listens to us. Visit radioambulante.org/encuesta. Thank you very much in advance. Again: radioambulante.org/encuesta.

This series was produced with the support of Movilizatorio and Alianza Potencia Energética Latam.

Eliezer Budasoff: To get from the Ecuadorian Amazon to the Peruvian one, journalist Joseph Zárate had to travel a total of about 6 hours by boat. First, within Ecuador, from Yasuní.

Joseph Zárate: I left with Holmer’s family, this park ranger who lives in this community called Llanchama, a Kichwa community. We went by boat to Nuevo Rocafuerte, which is like a town center on the border between Ecuador and Peru.

Silvia Viñas: It’s on the banks of the Napo River, a river that will be very important in this episode, one of the protagonists, we could say.

Joseph: It originates, let’s say, in the Ecuadorian Amazon and travels hundreds of kilometers until it reaches the Amazon. More or less where Iquitos is located. The Napo River is a historic river for the Kichwa people. Some leaders told me that in ancient times, Kichwa men traveled in their small rowboats, right? Sometimes for up to a year, going to look for salt, in that area where Iquitos is now, where the Marañón River is now, around there. And then they would return to their community, and they would spend many months, right? It’s a very important river.

Eliezer: From Nuevo Rocafuerte, Joseph traveled another three hours by boat until he reached the Peruvian side. He recorded this voice note.

Joseph, voice note: Well, it’s almost four in the afternoon and I’m in Cabo Pantoja. It’s the first town center after you cross the border between Ecuador and Peru. I arrived early today…

Joseph: Well, Cabo Pantoja is a community characterized by having a military base there that protects the border.

Joseph, voice note: What you can hear is the helicopter, flying in circles, basically.

Joseph: Military helicopters keep flying overhead because in that area there’s a very strong presence of coca leaf cultivation. Illegal coca leaf cultivation. Several reports have already been published. For example, there’s a report from Amazon Watch that indicates there are armed groups present in that area, right? And they’re fighting over drug trafficking corridors and illegal gold mining territories.

Eliezer: In this episode we’re going to explore what you found during your journey through the Peruvian Amazon. But what would you say, in principle, is the biggest difference between what we saw in Ecuador and the situation in Peru?

Joseph: I would say that the biggest difference you can see when you go from one country to another has to do above all with how the threats that indigenous communities face become more acute.

You can also see an impact from deforestation. Illegal gold mining dredges have also been seen. And certainly, also on the Ecuadorian side, where there are oil platforms, when there are oil spills, since the river is the same, even though the country is different, if there’s an oil spill in the Ecuador part, well, all that fuel keeps flowing down to Peru and contaminates there too, right? So, certainly in Ecuador and in Peru they face the same problems, but from what I’ve been able to see traveling these rivers, as the river gets bigger, so do the problems. You can also see how the defense of the territory is suffering degradation.

Silvia: This is Amazonas Adentro, a series from El Hilo, from Radio Ambulante Studios. Episode 3: The Watchmen, the River, and the Opportunists.

Joseph: Almost across from Cabo Pantoja, a few minutes away, there’s a community called Dos Fronteras. I think the reason for the name is obvious. We’re there in the border zone.

Maricruz Canelos: We’re in the native community of Dos Fronteras walking with our fellow monitors.

Joseph: And there I met a 33-year-old young woman named Maricruz Canelos, who is an environmental monitor for the Dos Fronteras community. And I also met Humberto Ramos, who is the community president.

Humberto Ramos: We do the work of conserving our territory as the Peruvians that we are.

Joseph: And also vice president of Orkiwan. Orkiwan is the Kichwaruna Wangurina organization of Upper Napo. It’s the organization that brings together the leadership of the communities between Cabo Pantoja and roughly Santa Clotilde, which is another community several hours downriver. And when I arrived, well, the first thing I saw was a flood.

Humberto: Nature is flooding us and this flood comes and damages our crops, because our territory—the majority of it—is lowland and the flood inundates us.

Maricruz: Here every year in July it rises and leaves the field badly flooded, right?

Joseph: Every year there’s flooding, every year the river rises. But they told me it had never risen so much, right? That’s what worried them most.

Joseph: And what do you think causes these things to happen? Why do these things happen?

Humberto: Because of climate change from El Niño and all that that’s being known and these are the things that nature sends and we really have no way to control it.

Joseph: In the last decade, the Peruvian Amazon, especially that part of Peru, has been facing an increase in climate changes. So of course, before, during the dry season or low water period, as they call it, and during the rainy season, it was very marked, right? Each year. But now this can no longer be defined clearly. That is, people no longer know very well when the dry season will start, when the rainy season will start, and how long it will last.

Joseph: One thing he mentioned to me is that when the water comes from Ecuador there’s also a lot of contamination.

Humberto: Yes, exactly. And that’s what damages the plantain the most.

Joseph: If an oil spill occurs, right? On the platforms near Yasuní, of course, since the river is always flowing down to Peru, this contamination immediately affects the community of Dos Fronteras and the others.

Humberto: It contaminates everything and kills it and you can no longer consume it because we pull out the yucca and it comes out contaminated with oil. You can no longer eat it and that’s concerning.

Joseph: Of course, the water too.

Humberto: The water can’t be drunk because it’s contaminated. Our children suffer from anemia and all that, it’s very concerning. And sometimes the competent authority doesn’t come around here and thinks we’re living happy, calm, when it’s not like that.

Joseph: There is illegal mining, too. The use of mercury, as we’ll see later, that contamination also affects the Dos Fronteras community. Certainly, there has also been a series of impacts caused by land invasion, for example. Communities that are on the Ecuadorian side invade the territory of the Dos Fronteras community. So, even though the military provides security and watches over the territory, if there’s an impact on one side, it will affect the other. Water flows and runs and is unstoppable. So I think what I saw in Dos Fronteras is an example of that—of that immediate cause-and-effect of what occurs in that area of the Amazon.

Eliezer: At one point you sent us a voice note…

Joseph, voice note: We’ve just arrived at the community of Santa María de Angoteros. We’ve sailed for about three hours to get to this community…

Eliezer: Where you said you were going to see the monitoring done by people who use GPS to watch risk points.

Joseph, voice note: Of certain threats, using, well, GPS technology, using applications to be able to watch some risk points.

Eliezer: What were you referring to with that?

Joseph: It’s very interesting, right? I met Jaime Cárdenas, he’s the regional coordinator of the Rainforest US Foundation programs.

Jaime Cárdenas: I’ve been working with them for about eight years now. I’m an engineer specializing in Tropical Forest Ecology. I’m 33 years old.

Joseph: Very, very skilled, because of the experience he has traveling through that area.

Jaime: The monitoring consists of communities today being able to adopt technological tools, because ancestrally they continue caring for their territories, but additionally, well, today the element of technology is added.

Joseph: Jaime told me that they adapted an application that’s normally used by people who climb mountains, who do trekking, right? It’s called Locus Map. So they adapted it so that these indigenous environmental monitors can use it without needing to know too much about technology, right? So, in a more intuitive way. And of course, they can also use this application without needing to be connected to the internet. So, what do they do with this application?

Jaime: They can locate themselves in real time as they’re walking. They do surveillance, a walk, a patrol through the territory and, well, there’s the alert about threats that may exist within these communities.

Joseph: They can identify risk points through GPS. What do they call risk points? It could be, for example, a tree that has fallen across the path. Or suddenly an illegal plantation, right? Of coca. Or it could also be the presence of an illegal mining dredge. So, through this application on the satellite map, they can identify how far it is from the community. They can draw on the map the route they take and that way they can keep watch, right? And later, those who provide training at Rainforest go to the community and collect that information to systematize it and be able to somehow do a much more sophisticated type of monitoring, right? of the territory.

Silvia: If they’re using technology, I imagine many are young.

Joseph: Yes, the majority are young. I was telling you a moment ago, Maricruz, for example, who is 33 years old. And it’s very interesting in her case, right? Because…

Jaime: Before they were… All men. All men. All. And little by little it’s been seen, saying that… We also in the assemblies motivate them, we encourage them that this is not only a job that men can do, but that women also have the capabilities to do it.

Joseph: They wouldn’t let them.

Jaime: They wouldn’t let them. That is, many times machismo is very strong in this area.

Joseph: So, having a female monitor and having, let’s say, the presence of women leading that work, I think is very important, right? In fact, when I was talking with the folks from Rainforest, they told me that since the launch of this forest monitoring program they have, right? the number of Kichwa, Ticuna, Matsés women—which are other indigenous peoples—has grown from… They started with three and now there are 34. There are monitors, trainers, project coordinators.

Maricruz: I’m also a women’s leader, treasurer of the apu and I have more positions.

Joseph: Like what? For example

Maricruz: Health promoter, too.

Joseph: That’s a sign, right? Of the empowerment of these monitors.

Joseph, voice note: Well, it’s six in the morning on July 16th. Now we’re in Santa Clotilde. It’s a town center that’s getting closer and closer to Iquitos.

Joseph: Once we made this first journey through this part, the upper part of the Peruvian Napo, let’s say, we arrived at Santa Clotilde, which is also on the banks of the Napo River. Santa Clotilde is where the jurisdiction of Orkiwan ends—which they’ve been able to settle, to consolidate the union among them, the organization, to prevent, for example, illegal gold mining dredges from continuing to affect their territory. From Santa Clotilde to roughly Mazán or Iquitos, which is the more urbanized area, it already belongs to another federation, which has other communities. So this other federation—the communities are also Kichwa—but from what the residents told me, the organization is a little weaker, right? Why? Because there aren’t only Kichwa people there, but there are mestizo people, there are people from other places, so the organization is a bit more complicated there.

Joseph, voice note: Today we’re going to visit the last community called Vista Hermosa, which is on the banks of the Tambor Yacu River, which is about three hours away…

Joseph, voice note: You have to walk carefully…

Joseph: So Vista Hermosa is a Kichwa community.

Joseph: And there I was also able to meet a monitor who was the president of the Vista Hermosa community named Silda.

Silda Dahua: My name is Silda Dahua Sandoval Depapa. I’m 49 years old. I’m apu of the native community of Vista Hermosa.

Joseph: She, together with two other companions, go walking through the territory, right? According to how the application indicates to them.

Silda: Here we’re going to reference this wall, we’re doing the work.

Joseph: They open the application, certain red points start appearing. Each red point is a risk point, right? So they have to go to the red point to find out what type of risk it is. We went through an area of their community to be able to look at one of those points.

Silda: We’re going to describe it here.

Joseph: So there you mark the point you’ve come to watch. You put a description, right?

Silda: Doing…

Joseph: Monitoring. right?

Silda: How do I write to you? How do I tell you?

Joseph: With the journalist.

Silda: Okay, with the…

Joseph: Journalist.

Joseph: We walked for about 40 minutes. She was telling me about the series of problems there are in her community. One of the most serious is that some years ago they were in need of obtaining the legal title to their territory.

In Peru, unfortunately, there are many communities that don’t have legal title to their territory, that is, they’ve lived there for a long time, but they don’t have the legal document. And to be able to get the community’s property title you need money, money that they often don’t have. So, what Silda told me was that an habilitador(middleman) arrived, a timber businessman, let’s say.

Silda: He held a meeting saying that he’s going to work extracting timber and he wants to get the community’s title.

Joseph: Offering to help them get their property title in exchange for extracting timber from their own community. That is, he told them: you give me permission to extract timber from your community, from your territory, and I’ll pay the expenses to be able to title the community. So they said, well, perfect. One thing for another, right? A win-win, let’s say, as they say. But what happened? The middleman (habilitador) left, time passed and they wondered: hey, but hasn’t he come to extract timber?

Silda: He only wanted to do what they call, there’s a word that’s used: timber laundering. They say he’s extracting from here, from the Vista Hermosa territory, but he hasn’t extracted even once from here.

Joseph: So, at one point the forestry authorities went to the community to verify whether or not this businessman had extracted timber. And it turned out he hadn’t extracted timber from there, but from somewhere else. But the middleman had used the signed permit from the community, claiming they had extracted timber from their community. So, of course, the ones who got fined were the community and not the middleman.

So, when the Vista Hermosa community realized all this, around 2018, Vista Hermosa owed the forestry authority an amount exceeding two million soles. And two million soles, in fines, is just over half a million dollars. It’s a lot of money. Basically they had been scammed.

The most concerning thing about that is that this scam occurred during three different apu administrations of the community. Of course, after this experience they expelled them, that is, they no longer let these people enter. Because of course, okay, they suffered this scam, this problem they’re now resolving through conservation. But they’re not going to be fooled again. They know the laws, they can transmit knowledge about caring for the territory, they have the support of these organizations. But what I don’t see is the support of the Peruvian State. That’s what I don’t see. Many times the responsibility for caring for the territory falls, or tends to fall, on indigenous communities. Ah, indigenous communities are the defenders of the Amazon, and that sometimes makes people forget that those who must defend those territories, above all, are the States—that’s what they were created for. But what happens is that the States leave them defenseless.

Silvia: We’ll take a break and come back.

Eliezer: We’re back.

Plinio: How are you, Roque? How are the monitors?

Joseph: After being with Silda, we left the Tambo Yaku river basin. We kept going down, right? And in the last community we visited that day, already in the afternoon, we arrived at Nuevo San Roque.

Plinio: The monitors?

Monitor: Here we are.

Plinio: I need the cell phones to check the data in order to pay.

Monitor: Yes.

Joseph: It was very interesting and very disturbing, too, what we found, right? Again, we were going to drop off donations. And there we went to look for the apu of the community. And the apu, well, came out and was in a certain state of inebriation, right? From the chicha he had drunk.

Plinio: Has the miner offered you anything or not?

Apu: No.

Joseph: I remember very well that one of the colleagues from Rainforest US, Plinio Pizango, head of technology transfer for the foundation, and who also leads the training programs for monitors in that territory, told the apu, half-jokingly, half-seriously: Hey, and they’ve told me that now you’ve become a miner. And the apu told him: No, no, engineer, no! We’ve expelled the miners. That’s what he said first, but then the apu began to tell the truth.

Apu: Look, out of necessity there was a little boat, it was here.

Plinio: Yes, yes.

Apu: Which I would like to say in reality, Engineer.

Plinio: Of course, that is, that’s why I came to talk with you, because they had seen a small boat stationed here.

Joseph: And he told us a very disturbing story. He told us…

Apu: It was to celebrate our anniversary.

Plinio. Yes…

Joseph: That the community’s anniversary had occurred a few weeks ago and that they didn’t have money to be able to buy some pigs to make food for the community, right? To invite people… Because always in Kichwa culture, well, when there’s a community anniversary, all the other communities come to your house, to your territory to celebrate, with chicha and with meat and with many things. So when an illegal gold mining dredge arrived, it told them: well, I’ll give you 500 soles and you let me stay here a few weeks, let’s say, right? And well, they accepted the money.

Plinio: You’ve always worked very well, protecting the territory, not letting loggers in, not letting illegal miners in. You know that this man commits a crime, right? Yes. And tomorrow or later, when they catch him, he’s going to say: it wasn’t me. He’s going to say I’m here with the apu’s permission. And how will you look then?

Joseph: And they let the dredge stay there for almost a month. Until they said: well, the engineers from Rainforest are going to come, so it’s a good time to expel him, right? And they expelled him. But well, that is, when I heard them and they explained all this, I also tried to understand the circumstances in which they live. Certainly, Nuevo San Roque, like many of the other communities I visited, lives in a state clearly of poverty, right? of very, very deep poverty.

They told me that there was no medical post there either, there were no basic services and work in the chacra had been affected by floods too. I kept thinking really about how necessity itself pushes—or pushes you in certain circumstances of your life—to do things you maybe don’t want to do. To do things that maybe go against your own integrity, your own health, right? And maybe when you begin to do them and sustain that activity for many years, suddenly you realize it’s too late to go back. What was happening in Nuevo San Roque was also the beginning of what’s been occurring in other areas of the Peruvian Amazon, right? Only now in those areas, illegal gold mining has taken over almost everything, right? They started like Nuevo San Roque, letting in one, two dredges for a time, but now it’s very hard for them to recover their own territory.

Today, well, we’re talking about mafias in a regional conservation area of Alto Nanay. Alto Nanay is a district that’s crossed by three rivers: the Nanay River, the Pintuyacu River and the Chambira River. So, the river that’s most taken over by illegal gold mining is the Nanay River. So, I traveled to the upper part of the river.

Joseph: So that you have an idea and can picture it in your mind, right? In the lower part of the Nanay River, which is the part closest to the city of Iquitos, there’s an area of beaches that, at least four months a year, when there’s low water, when the river drops, let’s say, some beautiful beaches of white sand form, right? I actually went to one of them called Playa Muyuna, where concerts are held, film exhibitions, etcetera. It looks like a beach from the Caribbean, basically. With very loud music, cumbias, etcetera. People having fun, eating.

And I was thinking when I was there, that people have no idea what’s happening in the upper part of that same river. There are these mafias, there are these dredges, which are small boats made of wood, many times, that suck through hoses from the riverbed, extracting the earth and filtering it to be able to capture the gold particles. And with mercury, which is a toxic metal, a liquid metal, what they do with those particles, those small gold particles, is amalgamate them, join them together, and once they join them, they boil that mixture, that amalgam so the mercury evaporates and only the gold remains together, the amalgamated gold.

Claudia Vega: All the miners arrive like: the State doesn’t give you anything, that’s going to give you quick money. What the miners don’t explain is that after they finish extracting the gold, the forest is contaminated, the water is contaminated and the cost to the population’s health is very high.

Joseph: To be able to better understand this impact, I interviewed Claudia Vega, who is coordinator of the mercury program at CINCIA, which is an NGO. CINCIA means Amazon Scientific Innovation Center. She’s a Salvadoran scientist

Claudia: I’m 47 years old and I’ve been studying mercury in the Amazon for a little over 15 years. I started in the Brazilian one and right now since 2017 I’ve been here in the Peruvian Amazon.

Joseph: So, CINCIA scientists, in collaboration with the Frankfurt Zoological Society Peru, conducted a study in six indigenous communities in the basins of the Nanay and Pintuyacu rivers, which are the basins where I was doing fieldwork. And this study focused on documenting and evaluating the level of mercury contamination in people and also the fish that are the basis of these communities’ diet.

Claudia Vega: The main route of mercury exposure in humans is the ingestion of contaminated fish. If the mother eats contaminated fish or fish with high levels, the fetus receives that, and although the mother doesn’t show any symptoms, the fetus—the baby—can be born with visible symptoms and symptoms that are irreversible.

Joseph: Like what?

Claudia: They can have silent symptoms, like learning difficulties, speech difficulties, memory difficulties.

Joseph: The results of CINCIA’s study are, of course, concerning. Of the 273 hair samples taken from people living in these six Alto Nanay communities—we’re talking about Diamante Azul, Santa María de Nanay, among others—79% of these samples, that is 215 people, presented mercury levels above the maximum limits established by the World Health Organization. And on the other hand, when we talk about the fish evaluation, the results are also concerning. CINCIA researchers collected about 284 individual fish of 43 species in cochas (oxbow lakes) and in different areas of the Nanay River. Of this sample, 14% exceeded the WHO recommended value for human consumption of mercury. So we’re facing clear contamination by this toxic metal.

Claudia: What happens in the Amazon region? Mining activity occurs without control and it doesn’t only occur in Peru, it occurs in Brazil, it occurs in Colombia, it occurs in Ecuador. I feel that the Nanay—since it has one thing, that mining is increasing—gives us again an alarm signal before the disaster happens. And it’s something that can be prevented.

Joseph: If nothing is done?

Claudia: We can have a disaster.

Joseph: Like what, for example?

Claudia: Populations will continue consuming fish and if I contaminate those fish, populations will be exposed to high mercury levels. And who does that affect? Mainly children. We’re compromising the new generations.

Edgar Isuriza: Illegal mining affects our health a lot. For example, here we have a child now, a girl who was born deformed, without little hands and without little arms, without little legs.

Joseph: Edgar Insuriza is former communal president of Santa María del Nanay, a peasant community.

Edgar: Going back years, we had fish in abundance. But when this mining comes in, the fish are contaminated and when they’re contaminated they don’t buy from us, they don’t consume from us.

Joseph: He was also analyzed along with his family, and well, the result of that study showed that they also have high mercury levels in their bodies. And he talked to me about the permanent concern he has about that. He also talked to me about how when he was an authority, right? Communal president of Santa María, he was very confrontational in facing the threat of mining. He organized the leaders, the communities, to close the river at one point and prevent boats that bring fuel to sustain the illegal dredges in Alto Nanay from continuing to arrive. And for that work, that confrontational work, he has been threatened, has been watched by these mobsters.

Edgar: There in that conservation area, that’s where the… We were talking about 75 dredges, today we already have information that there are 120 dredges.

Joseph: Edgar also mentioned this to me. Well, really, everyone, right? And one person said something that’s already known: when you’re talking, for example, not only with the Alto Nanay leaders, but you talk with people from the Prosecutor’s Office, you talk with people from NGOs working in that area. When you review news articles about what’s been happening in that place, they all mention Alvarenga.

Edgar: It’s a native community of about 12 families, natives from there. But since they’ve gotten involved in the mining issue, well, we were talking about 30 families. Colombians, Brazilians, Venezuelans.

Joseph: In Alvarenga, well, according to what they tell me, there are various groups that many times have entered that Alto Nanay area saying they’re tourists, right? But in truth, they’re not tourists; rather, they’re people who work in illegal mining and, well, control hasn’t been able to be exercised in that territory because many of these groups are armed.

They also talked to me about the presence of some members of FARC dissidents. For example, there’s a kind of territory taken over by illegal mining. And what the leaders told me is that they didn’t recommend I go there, because sometimes not even NGOs arrive, not even the Prosecutor’s Office dares to go there. They’ve gone there, but it’s not like they go very often precisely because of this, right? Because of this defenselessness.

Edgar: The Police, the Navy, the prosecutor’s office—they’ve gone to carry out operations. They blow up 5, 6, 7 dredges at most. A month ago they blew up 20 dredges, but right now there are 40.

Joseph: It’s certainly a very dangerous area. I was able to go to a certain point, right? I got to a community called Puca Urco. And I saw—I took photos and such—of a couple of dredges that were working there in front of Puca Urco. And what surprised me most is that they were doing their work in broad daylight and without any problem. That is, as if they were sure that no one’s going to come and blow up their dredge. No military. No police.

Joseph: I was also able to see… We went into some bars to talk with people, right? We saw there also a large presence of young Colombian and Venezuelan women who, according to what the residents tell me, are engaged in prostitution. Many of the young men working in illegal gold mining spend their money on that. From what they told me, for example, to spend a night with one of them, one can spend between one and two grams of gold.

Joseph: I was able to document that, obviously trying to maintain a low profile. We slept, spent the night in Puca Urco, but in the boat. So the next day, when I woke up and went to look for something to eat, when I got off the boat, one of the dredge operators approached me and asked me in a very, very aggressive way what I was doing there, if I was a journalist, what I was doing there, not to be asking questions, not to get into trouble. In a very threatening way. He was threatening me, certainly. So we had to leave a few hours later from that place because, well, it was very dangerous. So, when we arrived at Santa María del Nanay, already traveling down by public boat, I was able to talk with one of the leaders I interviewed.

Joseph: I haven’t been alone.

Leader: I’m not telling you they’re very…

Joseph: They’re… it’s that yes, there was one who threatened me.

Joseph: One of the leaders who was being threatened told me they had received news, a call from Iquitos from a character called Papillón, who’s a gold mining kingpin, who had given notice that there was a journalist…

Who wears black glasses, who’s always dressed in black, who has the description of my person, basically, who was asking questions and was traveling to the communities and that as soon as I arrived at one of them, well, they should stop me and take my things—to prevent me from doing the work,

Joseph: I thank you for letting me know anyway. But they think I’m just going now…

Leader: Right now they already know everything…

Joseph: But well, fortunately I was able to leave that place before that happened. And that gives you an idea, right? Of how dangerous, how disturbing that place is. When I also had the opportunity to talk with sources from the Prosecutor’s Office, from the Environmental Prosecutor’s Office of Loreto, there in Iquitos, they also talked to me about the almost non-existent budget they have to do their work. I remember very well that one of them showed me the bulletproof vest he has and told me: that vest is a donation. That is, they don’t even buy them the vest, right? To be able to use the Navy’s helicopter, for example, they have to ask the navy as a favor for a couple of hours to use the helicopter. That is, they don’t have money. And then I was also able to see some videos they’ve recorded of their interventions.

Prosecutor agents: Why the hell are you coming?!

Joseph: And when you see the videos and hear the audios—how they confront each other, with weapons, with gunfire.

Prosecutor agents: Get back!

Joseph: It’s very disturbing, very concerning, right? What’s happening there and everything the leaders have to go through, in addition to the contamination we’ve talked about.

Prosecutor agents: You’re committing a crime!

Eliezer: We’ll take one last break and come back.

Joseph: That is, here they’ve done mining.

Mercelina Angulo: Yes, here they’ve done mining. Up to there was the beach, but since they did mining, this got hollowed out, that is…

Joseph: It’s been destroyed.

Marcelina: Everything’s been destroyed and it remains as it is.

Silvia: Before reaching the Triple Frontier, where Peru, Colombia and Brazil converge, Joseph visited one last area of Alto Nanay.

Joseph: Which is the area where the Pintuyacu River is. A very close area, because the Pintuyacu River is a river whose waters flow into the Nanay River. They’re connected rivers.

Marcelina: We really have a lot of minerals. But what good is it to work a mineral if it directly affects us as human beings?

Joseph: We met Marcelina, who came to pick us up in her motorboat.

Marcelina: My name is Marcelina Angulo Chota. I’m the vice president of the Management Committee of the Regional Conservation Area.

Joseph: A very admirable woman, especially for the stories she told me. She’s also a leader who lives under threat.

Marcelina: ‘Hey ─he tells me─, just like you screwed me, I’m going to screw you. You took everything from me, I know where you live. I’m going to start where it hurts you most. It’s going to hurt you a lot because children are what matter, but if not, you don’t keep doing this. I’ll continue from the youngest to the last, which is you.’

Joseph: Marcelina is 41 years old and is also a mother. She has 4 children.

Joseph: How many people roughly live here in Saboya?

Marcelina: Here in Saboya there are 35 families.

Joseph: And that’s the biggest community, they tell me.

Marcelina: This is the largest community there is among the six siblings.

Joseph: She lives in a community called Seis Hermanos. It’s called Seis Hermanos because it’s composed of six annexes, each with its own name. And the main annex of the Seis Hermanos community is one called Saboya, where Marcelina spent her childhood. And while we walked she was telling me about the surveillance work they’ve been doing. She told me that some time ago in that Pintuyacu area there were illegal mining dredges.

Marcelina: What we did is organize ourselves. We removed them; they went in boats to remove each one. Some took their weapons and some went prepared also with sticks, in case something could happen. To talk with them directly, and we gave them only a few hours to leave, and truly, they left.

Joseph: Thanks to the organization of the annexes of Seis Hermanos, right? The six siblings came together, let’s say, to be able to expel these dredges, making surveillance groups.

Marcelina: We had no contact with the police, or with the Navy, or with the prosecutor. That’s how we’ve done our work, alone, organized, as a community.

Joseph: The regional government or the authorities don’t support them. At one point she showed me a completely rusted, broken boat that didn’t have a working engine because they didn’t have money to send it for repair. There’s a need for resources to be able to make that defense.

Marcelina: You know what the dredge operators are afraid of? That we organize as a community. The community has more strength than if you come from another place and want to remove them because you don’t know the reality. Why it’s increased and why it continues as it is—it’s because the authorities themselves have held back at the central, middle and district levels.

Joseph: What Marcelina told me with concern was that, of course, they’ve organized, they’ve done what’s possible to expel these dredges. But the necessity is so great that some leaders, according to what Marcelina told me, have started to think whether it might not be a good idea for them to let the dredges in. And certainly, that again puts us in a complicated situation, right? That one in human terms can also be understood. That is, one thing Marcelina told me is: of course, we’ve been defending this territory without money, with our own resources, with our own energy, putting our life and our families at risk. But on the other hand there’s this offer, right? This offer of being able to have an income, of being able to have an economy. So we don’t know how much longer we’re going to resist. She’s convinced, of course, that she’ll continue forward despite the threats. But she doesn’t know what can happen later.