CECOT

252 venezolanos

Jhoanna Sanguino

Widmer Josneyder Agelviz Sanguino

Venezuela

Estados Unidos

El Salvador

Donald Trump

Nayib Bukele

Nicolás Maduro

Marco Rubio

El sobrino de Jhoanna Sanguino es el primero que sale en la lista de los 252 venezolanos que Estados Unidos deportó ilegalmente a El Salvador. Se llama Widmer Josneyder Agelviz Sanguino y acaba de cumplir 25 años. Jhoanna dice que ver su nombre en esa lista le causó un dolor enorme, pero también la llevó a actuar. Una vez que supo dónde estaba –en la megacárcel de máxima seguridad de Nayib Bukele– hizo lo posible para sacarlo. Hablamos con ella el día después de que Widmer regresara a casa como parte de un canje de prisioneros entre Estados Unidos y Venezuela. Jhoanna es una de las decenas de familiares que durante meses defendieron la inocencia de los venezolanos deportados ilegalmente al Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo, el CECOT. Ahora que están libres, piden justicia a gobiernos que han convertido sus sistemas penales en herramientas de criminalización y operación política.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Silvia Viñas, Mariana Zúñiga -

Edición

Eliezer Budasoff -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción digital

Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo -

Tema musical, música, diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elías González -

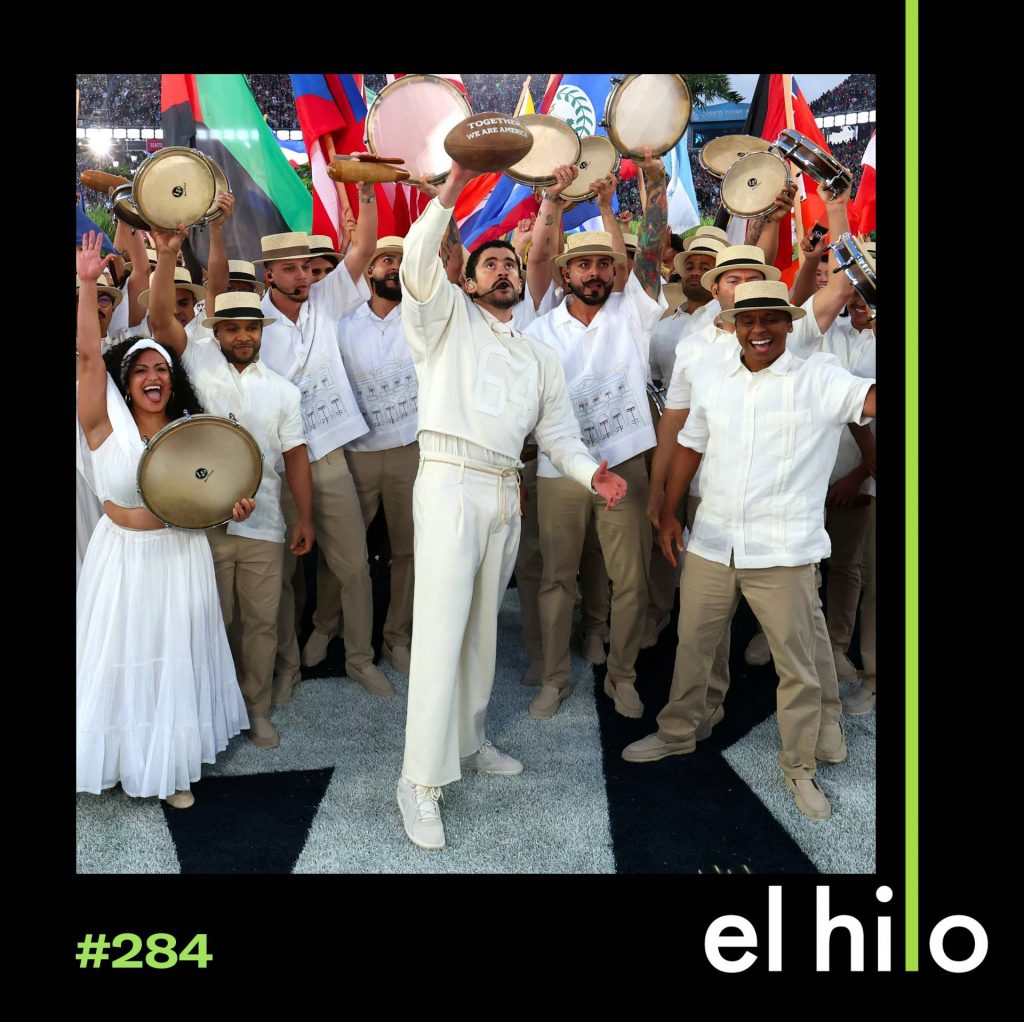

Fotografía

Getty Images / Marvin Recinos

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Silvia Viñas: Lo primero que quería preguntarte es. ¿Cómo estás? ¿Cómo han sido estos días?

Jhoanna Sanguino: Ay, estos días. Bueno, a partir de ayer sentí una emoción que nunca había tenido la oportunidad de experimentar. Es la alegría más feliz y el sentimiento más hermoso que he sentido desde que nací. Es algo inexplicable, Silvia.

Mi nombre es Jhoanna Sanguino. Soy la tía de Widmer. Widmer Josneyder Agelviz Sanguino, uno de los jóvenes deportados injustamente a El Salvador. Y bueno, ya lo tengo conmigo, ya puedo decir misión cumplida y agradecerle primeramente a Dios.

Mi objetivo siempre fue claro y fue demostrar la inocencia de Widmer, porque sabía que lo que se había hecho con él desde un principio fue una injusticia. Él ingresó a los Estados Unidos protegido. Él ingresó a los Estados Unidos refugiado por reasentamiento, y aún así lo deportaron. Entonces, ese fue siempre mi objetivo: buscar su liberación y demostrarle al mundo entero de quién era mi niño, de cuál era la injusticia que habían cometido con él.

Silvia: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer Budasoff: Y yo soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Widmer, el sobrino de Jhoanna, acaba de cumplir 25 años. Es uno de los 252 venezolanos que Estados Unidos deportó a El Salvador en marzo. Pasaron cuatro meses encarcelados en el Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo, el CECOT, la megacárcel de máxima seguridad que construyó el gobierno de Nayib Bukele.

Silvia: Se suponía que El Salvador sólo iba a recibir a los que Bukele llamó “delincuentes convictos”. Pero la gran mayoría –entre ellos Widmer– no tiene antecedentes penales. En julio regresaron a su país como parte de un intercambio por presos políticos y estadounidenses que estaban detenidos en Venezuela.

Eliezer: Hoy, la historia de los familiares que defendieron la inocencia de los venezolanos deportados al CECOT y las consecuencias de caer en manos de sistemas penales que operan fuera de la ley, al servicio del poder político.

Es 15 de agosto de 2025

Jhoanna: Nosotros somos de un pueblo andino hermoso llamado el estado Táchira. Nosotros estamos ubicados exactamente en la colina. Somos una comunidad de personas humildes, soñadoras, inteligentes, emprendedoras. Y allí nació Widmer también. Widmer también es de acá, del estado Táchira. Un pequeñín hermoso, lleno de sueños, inteligente, soñador, colaborador, hermoso.

Eliezer: Widmer fue el primer sobrino de Jhoanna. Ella tenía 10 años cuando nació.

Jhoanna: Yo cambié mis muñecas de trapo por un bebé de verdad. Es la luz de nuestros ojos. Sus primos lo aman, lo adoran. Para sus hermanos es un héroe. Le gusta mucho la mecánica, la electrónica. Desde que era niño desarmaba los equipos de sonido, los carros y conectaba una corneta del equipo de sonido que estaba en la sala y le hacía conexiones de cables para que la corneta le llegara hasta su cuarto y poder escuchar música.

Eliezer: Jhoanna se emociona mucho al hablar de Widmer. Se nota que es su protegido. Lo está cuidando de los medios, de la sobreexposición. Hablamos con ella el día después del regreso de Widmer, y quería darle espacio y tiempo para sanar, para descansar y pasar tiempo con su familia. Dice que tenemos que manejar este momento con cordura, con respeto. Así que ella nos contó la historia de Widmer.

Silvia: ¿Cuándo y por qué decide irse de Venezuela?

Jhoanna: Él se va de Venezuela en el año 2023. Él presentó un caso de asilo. Él se fue de Venezuela hacia Ecuador, allá estaba su mamita. Y en Ecuador es donde reciben el refugio por ACNUR. El caso de asilo también por seguridad de Widmer lo mantenemos también en completa reserva, por situaciones ajenas al país, sí, por supuesto. Pero, fue una situación de asilo pues delicada. Entonces, decide irse a Ecuador. De Ecuador ellos reciben el apoyo de ACNUR y de Ecuador sale a Estados Unidos en el año 2024, el 19 de septiembre del 2024.

Eliezer: Esto es importante. Widmer tenía permiso para entrar a Estados Unidos. Le habían aprobado el estatus de refugiado bajo un programa de reasentamiento de las Naciones Unidas. Es un proceso que puede demorar meses, o hasta años. Lo investigaron y verificaron sus antecedentes para garantizar que no era una amenaza a la seguridad pública de Estados Unidos.

Silvia: Pero Widmer nunca llegó a empezar su nueva vida allá…

Jhoanna: Él desde el primer momento que ingresa al aeropuerto, fue detenido.

Él ingresa al aeropuerto de Houston, llega como núcleo familiar en compañía de su mamá y sus dos hermanos. Su mamita es mi hermana mayor. Y ahí es donde lo detienen, argumentando que lo iban a detener por sus tatuajes, porque efectivamente lo relacionaron de inmediato los tatuajes que él tenía con el Tren de Aragua.

Silvia: ¿Pero entonces lo detienen antes de que empieza la administración de Trump?

Jhoanna: Exactamente. Fue antes. Sí.

Eliezer: En septiembre de 2024. Su tatuaje, en el antebrazo, tiene un reloj, un búho y una rosa. El agente que lo detuvo escribió en su reporte que eran imágenes asociadas a la banda criminal venezolana Tren de Aragua. Recordemos que Widmer no tenía antecedentes penales. No había ninguna otra evidencia que lo vinculara con el grupo. A Widmer lo movieron varias veces de centros de detención.

Silvia: Y mientras él está detenido, ¿se puede comunicar con ustedes, con la mamá?

Jhoanna: Sí, mi hermana le consignaba a él dinero para que se pudiera comunicar con ella y con su novia que estaba en Ecuador. Él habló con mi hermana por última vez el 13 de marzo, donde le manifestaba que iba a ser trasladado, no deportado, sino trasladado de centro de detención.

Eliezer: Dos días después, el 15 de marzo, Estados Unidos deportó a los 252 venezolanos a El Salvador. Los acusaban, sin pruebas, de pertenecer al Tren de Aragua.

Audio de archivo, periodista: La deportación se llevó a cabo el mismo día que un juez estadounidense bloqueó al gobierno de Trump usar la ley de Enemigos Extranjeros de 1798, que se utilizaba en tiempos de guerra.

Audio de archivo, noticiero: En un video difundido por el presidente Bukele puede verse cómo llegan en un vuelo esposados, y son trasladados inmediatamente hasta la mayor cárcel de América Latina, conocida como el Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo.

Jhoanna: Y ahí ya nos alarmamos, nos alarmamos porque él nunca duraba tantos días sin comunicarse. Y entonces dijimos: algo pasa.

Silvia: Me imagino que habían escuchado sobre el CECOT. ¿Tenían quizás una idea?

Jhoanna: Yo ya había escuchado antes de Guantánamo. Yo ya había escuchado Guantánamo, yo ya había tenido una conversación antes con mi hermana y le había dicho: “Caro, ¿cómo va la situación con el niño? Estoy muy preocupada porque están enviando a venezolanos a Guantánamo”. Incluso la esposa de mi hermana, un hijo de su compañera de trabajo, lo tuvieron en Guantánamo y es venezolano. Entonces yo le digo, “Caro, esto no está muy lejano a nosotros, tenemos que estar, o sea, muy pendientes y hablar con el abogado a ver qué se puede hacer, porque sí está sucediendo”. Y mi hermana me mencionaba: “No, tranquila, Jhoanna, no se preocupe, el niño está en un proceso de asilo y cuando ellos están en un proceso de asilo es imposible que los deporten. No se preocupe”. Entonces yo le dije, “ah, bueno, perfecto, está muy bien”. Y ella me decía, “no se preocupe, porque ya el niño tiene la última audiencia el 1 de abril y pues todo en su proceso ha salido bien, y tenemos fe de que su caso de asilo sea favorable”. Entonces yo le dije, “bueno, perfecto”. Eso fue antes.

Eliezer: Antes de que Estados Unidos deportara ilegalmente a cientos de venezolanos a El Salvador. Antes de no escuchar por varios días de Widmer, sabiendo que lo habían trasladado.

Jhoanna: Y es allí donde mi hermana desespera. Empieza a llamar a varios centros de detención porque él todavía salía en sistema. Mi hermana ingresaba al sistema y él todavía salía que se encontraba en el centro penitenciario de Hidalgo. Y fue hasta el día 20 de marzo, en horas de la mañana, que mi hermana logra comunicarse con este número hacia migración y a ellos le confirman de que sí, de que Widmer el 15 de marzo fue deportado a El Salvador. Y en horas de la tarde es cuando sale la lista y vemos que Widmer es el primero de la lista.

Silvia: Jhoanna se refiere a una lista que obtuvo la cadena CBS de los nombres de los venezolanos deportados al CECOT. El primero que sale es Widmer.

Jhoanna: Y ahí el dolor fue impresionante. Fue algo terrible, pero me llené de fuerzas. Apenas yo vi el nombre de Widmer ahí en la lista fue como si Dios me hubiera enviado un mensaje y me hubiera dicho: “Ya, te lo encontré. Es el primero de la lista y es el primero que vamos a sacar”.

Jhoanna: No sé cómo explicarte, pero ver su nombre ahí me permitió a mí accionar. Porque yo estaba de manos atadas, porque lo estaba buscando y no lo encontraba. ¿A quién demandaba, a quién le pedía ayuda? Si no sabía dónde estaba, o sea, no podía accionar. Pero, fíjese que ni siquiera el abogado tenía conocimiento de esto, porque el abogado habla conmigo y me dice, “pero es que Johana es primera vez en la historia de los Estados Unidos que yo veo una violación de los derechos de tal manera”. Me decía, “Johanna, me disculpas, pero no sé qué hacer. No sé qué hacer, porque en los más de 15 años de carrera jamás en mi vida me había encontrado con esto”, me decía el abogado. “Te quiero ayudar”, me decía el abogado, “pero no sé cómo, Johanna”. Me decía, “no sé cómo”.

Eliezer: Después de la pausa, Jhoanna va a El Salvador a buscar a su sobrino. Ya volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Jhoanna: Lo único que sabíamos de Widmer era que estaba en ese lugar porque lideraba la lista. Más nunca lo habíamos visto en ningún video, en ninguna foto. Yo no tenía certeza de que el niño estuviera allí. Empezamos a contactar a organizaciones, empezamos a trabajar en conjunto con su abogado, y se empezaron a hacer todas las acciones, para que se demostrara su inocencia. Al principio pareciera que fuéramos invisibles, pero sin embargo nunca, nunca, nunca perdimos la fe y accionamos. En cuanto a las acciones, fueron muchas.

Eliezer: Por ejemplo, a principios de mayo, presentaron una denuncia donde argumentaban que se había violado el derecho de Widmer al debido proceso. Un juez en Texas a mediados de ese mes le ordenó al gobierno de Trump que confirmara dónde estaba Widmer y le garantizara acceso a su abogado. Fue la primera orden judicial de ese tipo.

Jhoanna: Se le dio un lapso de 24 horas al gobierno americano de que nos diera respuesta y hasta la fecha el gobierno americano desoyó por completo esta orden.

Silvia: Los familiares de otros venezolanos deportados al CECOT también se movieron en esos meses para intentar sacarlos. Pusieron demandas ante la Sala de lo Constitucional en El Salvador, ante la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. Crearon un comité en Caracas para organizarse.

Jhoanna: Ese comité está formado por varias familias, pero a nosotros los del Táchira nos quedaba muy retirado. No podíamos asistir a reuniones, no podíamos estar como tan de lleno en todo esto. Se escapaba mucha información, pues, por lo que estábamos tan lejos. Entonces, nos vimos en la necesidad y en la obligación de crear otro comité, pero solamente con los del estado Táchira y con la ayuda del doctor Walter Márquez. Él es un ex embajador de Venezuela y también es el presidente de la organización El Amparo.

Eliezer: La Fundación El Amparo defiende los derechos humanos. Walter Márquez es historiador y fue diputado de la Asamblea Nacional. Los ayudó a crear el Comité de Familias de Venezolanos Tachirenses Deportados Arbitrariamente a El Salvador.

Jhoanna: Y es allí donde llegamos a la conclusión de que la próxima acción sería viajar a El Salvador. Viajar a El Salvador a introducir las demandas, a solicitar una visita. Porque cabe mencionar que así como yo, estaban muchas familias de que lo único que tenían de sus jóvenes era que su nombre estaba en esas listas, más nada. Entonces decidimos empezar a trabajar en base a eso, a recaudar fondos.

Silvia: Hicieron rifas, vendieron comida, amigos que viven fuera del país mandaron donaciones. La novia de Widmer en Ecuador hizo una rifa con sus compañeros de trabajo.

Eliezer: Consiguieron recaudar lo que necesitaban y viajaron del 10 al 13 de junio. Fueron pocos días, pero muy intensos.

Jhoanna: En El Salvador se hizo una solicitud de manera formal a la Dirección de Centros Penales, solicitando de que se nos permitiera visitarlo. Yo viajé por Widmer, pero también viajé en representación de seis familias tachirenses, de acá, de donde somos. Pero la lucha era por los 252 venezolanos, solamente que por circunstancias de la vida, por cuestiones ajenas, solo pudimos llevar un poder conformado por seis personas. Y era que se nos permitiera tener una visita y que se nos diera una fe de vida. Hasta la fecha no recibimos respuesta. También se hizo una demanda, también de manera formal a la Procuraduría de los Derechos Humanos, manifestando todos los derechos que se les habían violado a ellos. Hasta el momento tampoco recibimos información.

Silvia: También visitaron el Comité de la Cruz Roja, porque les preocupaba mucho el estado de salud de los detenidos. Y le pidieron ayuda a la Iglesia Católica.

Jhoanna: Yo había enviado también, desde mucho antes de contactar organizaciones y todo esto, había enviado yo un correo a una dirección del Comité de los Derechos Humanos de la Procuraduría, y ellos me respondieron de que me iban a contactar con los canales regulares para que se me diera información. Eso fue lo único que me respondieron, como que ellos no eran como que ellos no era el canal al que yo debía intervenir. Entonces yo le dije, “¿pero si no son ustedes quienes?”. Y hasta la fecha también me quedé esperando el correo de que ellos me iban a poner en contacto con los organismos ideales para eso. Hasta la fecha tampoco recibí respuesta. Entonces, como ya se habían agotado todas las vías nacionales, entonces, bueno, empezamos a accionar ya hacia las vías internacionales para la denuncia internacional ante La Haya. ¿Bien? Demandando a toda la cadena de mando del presidente de El Salvador: desde el que abre la puerta de ese lugar, hasta el que la cierra. Toda su cadena de mando. Porque efectivamente nadie respondía a nuestro llamado.

Eliezer: Las autoridades salvadoreñas tampoco han respondido a unos 70 habeas corpus que presentaron abogados en estos meses. El habeas corpus es un procedimiento legal que garantiza que las personas detenidas puedan ir ante un juez.

Silvia: La organización salvadoreña Cristosal estuvo acompañando a las familias desde el comienzo, con ayuda psicológica y legal. Crearon una plataforma para que los familiares pudieran agregar datos sobre los detenidos. Esto sirvió para documentar los casos. Cristosal trabajó con los parientes para dejar un registro que desmiente mucha de la narrativa falsa, como que eran miembros del Tren de Aragua. Cristosal también pidió información oficial, que les negaron cada vez.

Eliezer: También pusieron a los familiares en contacto con organizaciones de víctimas salvadoreñas del régimen de excepción. Estos grupos apoyaron públicamente a los venezolanos y a sus parientes. Encontraron una causa común: liberar a los que han sido detenidos de manera arbitraria e ilegal en El Salvador.

Jhoanna: Nos apoyó mucho Cristosal. No solamente a mi, a muchos salvadoreños, y en este momento se llena mi corazón de tristeza al leer públicamente el comunicado que ellos hicieron que les tocó abandonar El Salvador.

Eliezer: Cristosal tuvo que dejar el país luego de 25 años de trabajo en defensa de los derechos humanos. Esta es una organización que ha investigado y documentado corrupción en el gobierno de Bukele. También violaciones como torturas, abusos y muertes en las cárceles bajo el régimen de excepción que ya lleva más de 3 años.

Silvia: La policía detuvo a la directora anticorrupción de Cristosal, Ruth López, en mayo. Ruth era la abogada a cargo del equipo que acompañaba a los familiares de los venezolanos deportados al CECOT para preparar y presentar los habeas corpus. Trabajó muy de cerca con ellos. El comité de Jhoanna publicó una carta condenando su secuestro y detención.

Eliezer: Luego, en junio, entró en vigencia la Ley de Agentes Extranjeros, que prohibe que organizaciones que reciben fondos del exterior hagan actividades políticas, y exige que paguen un impuesto del 30% . En su cuenta de X Cristosal explicó que suspendían sus operaciones en El Salvador ante, cito, “la escalada de criminalización”. Siguen trabajando desde Honduras y Guatemala.

Silvia: El director de Cristosal, Noah Bullock, me contó que construyeron relaciones de mucha confianza con más de 160 familias. Ahora están ayudando a documentar los testimonios de torturas y malos tratos que recibieron los venezolanos en el CECOT: aislamiento, golpizas, abuso psicológico. Noah dice que lo que han escuchado hasta ahora muestra prácticas sistemáticas. El ejemplo más claro es escuchar a los venezolanos decir que el director del CECOT les advirtió que habían entrado al infierno, que no iban a salir. Porque eso revela la intención de deshumanizar, de castigar. Muestra que no es un sistema penitenciario que obedece al Estado de derecho, dice Noah.

Eliezer: Noah también nos dijo que la falta de respuesta a los habeas corpus por parte de la Sala de lo Constitucional de El Salvador muestra que el sistema de justicia operó en función de la impunidad y al servicio del régimen, en vez de proteger a las personas, como debería y enfatizó que el hecho de que cientos de venezolanos hayan estado desaparecidos en un centro penal de máxima seguridad, sin juicio, sin defensa, fue posible porque Bukele ha desmantelado el sistema democrático del país. Los venezolanos deportados al CECOT no eran “detenidos”, dice Noah, fueron rehenes.

Silvia: ¿Y tú cómo te sentías? No sé si te acuerdas cómo te sentías regresando después de esa visita al Salvador. Sentías como: OK, esto se está moviendo, hay una esperanza.

Jhoanna: Sí, yo, yo me vine llena de mucha esperanza. Yo viajé con la ilusión de verlo, por supuesto, pero en el fondo de mi corazón también estaba como que existe la posibilidad que no me lo dejen ver. Pero, las acciones que estoy haciendo tienen mucho poder, tienen mucho peso y sé que van a ser de muchísimo precedente para futuras acciones.

Eliezer: El Amparo, la fundación con la que han estado trabajando las familias del Táchira, está preparando una demanda ante la Corte Penal Internacional contra Bukele y otros miembros de su cadena de mando. Otras organizaciones empezaron el proceso para demandar a Estados Unidos en nombre de uno de los venezolanos deportados al CECOT.

Jhoanna: Los tres días que estuve allá no dormí, redactando cada uno de los documentos que se introdujeron, leyendo la Constitución salvadoreña, viendo a ver en qué artículos me podía apoyar, pero me vine satisfecha porque yo sabía Silvia, que cada una de mis acciones y cada una de las acciones que hacía cada familia iban a tener resultados. De pronto no de inmediato, Silvia. Pero yo sabía que cada acción tenía un fabuloso resultado y todo iba sumando. Y ayer, teniendo a mi niño conmigo, me doy cuenta de que sí, de que todo sumó.

Silvia: Ya volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Silvia: ¿Cómo te enteraste que lo iban a regresar a Venezuela? Cuéntame sobre ese momento.

Jhoanna: Ay, me enteré el viernes a las 07:00 de la mañana. Recibo una llamada de mi amiga Elizabeth. Ella es del comité. Nos hemos hecho muy, muy buenas amigas. Y me decía, “¿Johanna vio la noticia?” “No. ¿Qué pasó?” “Revisa, revisa el celular”, ella gritaba. Y yo: “Ya va, ya va. No entiendo nada”. Y veo todas estas noticias de que se había hecho el canje, de que había una negociación. Pero como ya antes nos habíamos ilusionado con algo parecido, yo soy, como decimos acá, muy arrebatada. Entonces, yo dije ya va Jhoanna, cálmate, vamos a esperar.

Eliezer: Le mandó un mensaje a Gris Vogt, una mujer méxico-americana que estuvo ayudando a las familias.

Jhoanna: Y a las 11:00 de la mañana Gris me responde el mensaje y me dice, “Jhoanna, es real”. Me volvió el alma al cuerpo. Empecé a llamar feliz a mi familia, a decirles: “El niño viene, se hizo el canje”. Mi hermano me decía: “¿Johanna, estás segura?” Yo le dije, “Sí, sí, estoy segura. Gris me dijo que sí”. Cuando llamo a mi hermana y le digo: “Es real, Carito, es real”. No, fue realmente maravilloso. Nunca, nunca, Silvia. Nunca mi corazón había experimentado esa emoción.

Silvia: Jhoanna quería ir a Caracas a recibir a Widmer. Pero los del Comité general de familiares, el que está en la capital, le dijeron a los que viven lejos que no viajen, que las autoridades entregarían a cada uno de los repatriados a la puerta de su casa.

Jhoanna: Entonces yo dije bueno, lo voy a esperar. Yo vivo en Colombia, me vine de inmediato para Venezuela, y esperar a pensar: la comida, qué comida le vamos a preparar, qué va a querer comer. Los vecinos: “¿A qué hora llega? Queremos recibirlo”. Y entonces empezamos desde el viernes: no, llega hoy; no, mañana; no, pasado, porque estaban siempre retirados. Nosotros vivimos siempre lejos del centro del país y llegó el gran día. Los agentes que los traían, de la Guardia Nacional de Venezuela, se comunican con mi cuñada y le dicen que ya viene, que los esperemos en la puerta de la casa, que tengamos las banderas de Venezuela, las pancartas, que lo recibamos como nosotros ya lo tuviéramos planificado, pero que ya vienen. Como ya estaba toda la comunidad acá nos organizamos y entonces, a donde nosotros vivimos hay dos vías para llegar. Estábamos en la incertidumbre: ¿Llegará por cuál de las dos vías? Los motorizados los estaban esperando.

Se fueron a esperarlo en toda la vía principal. Todas las motos tenían bombas. Su papá fue a recibirlo allá. Esos carros se conocen, porque como ya habíamos visto los videos de las otras familias, ya sabíamos cuál era el carro. Y cuando vienen subiendo, el niño me comenta que él ve todo eso y que el compañero le decía, “¿pero usted quién es? ¿Usted quién es? ¿Por qué está toda esa gente?” Y él decía, “No, yo no sé, no sé qué está pasando. Ellos son los de mi comunidad”.

Se vinieron todos en caravana y lo escoltaron. Lo acompañaron hasta la llegada. El protocolo formal era que ellos debían bajarlo, entregarlo en las puertas de la casa y en las manos de su familiar, pero las personas que lo traían no se imaginaban que iba a haber tanta gente. Y le decían a Widmer, “Pero ya va por donde nos bajamos. Hay mucha, mucha gente. ¿Cómo hacemos?” Entonces, él le dijo, imagínate yo que estoy gordita un poquito, y el niño le dijo, “esa gordita que viene ahí es mi tía, ella es mi tía”.

Cuando abrieron la puerta, yo estaba ahí esperándolo. Mi niño también estaba ansioso de que abriera la puerta de ese carro y apenas abren la puerta, lo primero que veo son sus brazos extendidos. Sus ojitos brillantes, su sonrisa hermosa. Y me extiende los brazos y me abraza y me dice, “Tía, tranquila, ya estoy acá. Estoy bien, estoy bien. Te amo”, me decía.

¡Mi chiquitín!

Widmer: Todo bien, Gracias a Dios ya llegué… Todo bien, ya pasó todo. Gracias a Dios.

Silvia: Después de que Jhoanna nos contara sobre este momento, la llamada se cortó. Hubo un apagón. “Bienvenida a Venezuela!” me dijo una hora después. Ya se le había cortado la luz más temprano. Por Whatsapp, unos días antes de cerrar este episodio, me contó que Widmer está disfrutando de las cosas más sencillas: cada bocado de comida, ver una película, salir y sentir el sol. Dice que quiere concentrarse en la barbería como un nuevo capítulo para canalizar su energía y creatividad. Tiene todo el apoyo de su familia. Y Johanna dice que verlo feliz y realizado es la mayor recompensa.

Eliezer: Después del canje y la liberación, los gobiernos de los tres países han tratando de sacar ventajas políticas. El ministro del Interior de Venezuela, Diosdado Cabello, dijo que los habían sacado del infierno a cambio de la liberación de “asesinos”. Como les contamos hace dos semanas, en Venezuela hay más de 800 presos políticos. Torturan en las cárceles del país y hay personas que han muerto por esos malos tratos.

Silvia: El intercambio también le ha servido a Bukele para continuar con su narrativa. Repitió que muchos de los venezolanos liberados enfrentan delitos graves, aunque ya sabemos que la mayoría no tenía antecedentes penales. Tal vez recuerden que Bukele había propuesto un canje de los 252 por el mismo número de presos políticos en Venezuela. El mes siguiente, detuvieron a Ruth Lopez, la abogada de Cristosal qué había denunciado múltiples casos de corrupción en el gobierno de Bukele. En El Salvador también hay presos políticos. Hasta marzo de este año, el Comité de Familiares de Presos y Perseguidos Políticos había registrado 28 casos.

Eliezer: Y en un comunicado, el secretario de Estado de Estados Unidos, Marco Rubio, celebró que, cito, “cada estadounidense detenido injustamente en Venezuela ahora está libre y de regreso en nuestra patria”. A la vez, su gobierno sigue deteniendo a migrantes sin antecedentes, a turistas que están de paso, a estudiantes extranjeros que participan en protestas, y a personas que cumplen con el requisito de ir a una corte de inmigración para regularizar su situación en el país.

Silvia: Este episodio fue producido por mí, con la ayuda de Mariana Zúñiga y Gabriel Labrador. Lo editó Eliezer. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido y la música son de Elías González.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Soy Silvia Viñas. Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Silvia Viñas: The first thing I wanted to ask you is. How are you? How have these days been?

Jhoanna Sanguino: Oh, these days. Well, starting yesterday I felt an emotion I’d never had the opportunity to experience before. It’s the happiest joy and the most beautiful feeling I’ve felt since I was born. It’s something inexplicable, Silvia.

My name is Jhoanna Sanguino. I’m Widmer’s aunt. Widmer Josneyder Agelviz Sanguino, one of the young people unjustly deported to El Salvador. And well, I have him with me now, I can finally say mission accomplished and thank God first and foremost.

My objective was always clear and it was to prove Widmer’s innocence, because I knew that what had been done to him from the beginning was an injustice. He entered the United States under protection. He entered the United States as a resettled refugee, and even so they deported him. So, that was always my objective: to seek his liberation and show the entire world who my boy was, what the injustice was that they had committed against him.

Silvia: Welcome to El Hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer Budasoff: And I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Widmer, Jhoanna’s nephew, just turned 25. He’s one of the 252 Venezuelans that the United States deported to El Salvador in March. They spent four months imprisoned in the Terrorism Confinement Center, CECOT, the maximum-security megaprison built by Nayib Bukele’s government.

Silvia: El Salvador was supposedly only going to receive those whom Bukele called “convicted criminals.” But the vast majority—including Widmer—have no criminal record. In July they returned to their country as part of an exchange for political prisoners and Americans who were detained in Venezuela.

Eliezer: Today, the story of the family members who defended the innocence of the Venezuelans deported to CECOT and the consequences of falling into the hands of penal systems that operate outside the law, in service of political power.

It’s August 15, 2025

Jhoanna: We’re from a beautiful Andean town called Táchira state. We’re located exactly on the hillside. We’re a community of humble, dreamy, intelligent, enterprising people. And that’s where Widmer was born too. Widmer is also from Táchira state. A beautiful little one, full of dreams, intelligent, a dreamer, collaborative, beautiful.

Eliezer: Widmer was Jhoanna’s first nephew. She was 10 years old when he was born.

Jhoanna: I traded my rag dolls for a real baby. He’s the light of our eyes. His cousins love him, adore him. For his siblings he’s a hero. He really likes mechanics, electronics. Since he was a child he would take apart sound systems, cars and connect a speaker from the sound system that was in the living room and make cable connections so the speaker would reach his room and he could listen to music.

Eliezer: Jhoanna gets very emotional talking about Widmer. You can tell he’s her protégé. She’s protecting him from the media, from overexposure. We spoke with her the day after Widmer’s return, and she wanted to give him space and time to heal, to rest and spend time with his family. She says we have to handle this moment with wisdom, with respect. So she told us Widmer’s story.

Silvia: When and why does he decide to leave Venezuela?

Jhoanna: He leaves Venezuela in 2023. He filed an asylum case. He went from Venezuela to Ecuador, where his mom was. And in Ecuador is where they receive refugee status from UNHCR. The asylum case, also for Widmer’s security, we’re keeping it completely confidential too, due to situations beyond the country’s control, yes, of course. But it was a delicate asylum situation. So, he decides to go to Ecuador. From Ecuador they receive UNHCR support and from Ecuador he travels to the United States in 2024, September 19, 2024.

Eliezer: This is important. Widmer had permission to enter the United States. He had been approved for refugee status under a United Nations resettlement program. It’s a process that can take months, or even years. They investigated and verified his background to guarantee he wasn’t a threat to U.S. public security.

Silvia: But Widmer never got to start his new life there…

Jhoanna: From the first moment he enters the airport, he was detained.

He enters Houston airport, arrives as a family unit accompanied by his mom and his two siblings. His mom is my older sister. And that’s where they detain him, arguing they were going to detain him because of his tattoos, because they immediately related the tattoos he had to the Tren de Aragua.

Silvia: But do they detain him before Trump’s administration begins?

Jhoanna: Exactly. It was before. Yes.

Eliezer: In September 2024. His tattoo, on his forearm, has a clock, an owl and a rose. The agent who detained him wrote in his report that they were images associated with the Venezuelan criminal gang Tren de Aragua. Remember that Widmer had no criminal record. There was no other evidence linking him to the group. They moved Widmer several times between detention centers.

Silvia: And while he’s detained, can he communicate with you all, with his mom?

Jhoanna: Yes, my sister would deposit money for him so he could communicate with her and with his girlfriend who was in Ecuador. He spoke with my sister for the last time on March 13, when he told her he was going to be transferred, not deported, but transferred to another detention center.

Eliezer: Two days later, on March 15, the United States deported the 252 Venezuelans to El Salvador. They accused them, without proof, of belonging to the Tren de Aragua.

Archive audio, journalist: The deportation was carried out the same day that a U.S. judge blocked the Trump government from using the 1798 Alien Enemies Act, which was used in wartime.

Archive audio, newscast: In a video released by President Bukele you can see how they arrive on a flight in handcuffs, and are immediately transferred to Latin America’s largest prison, known as the Terrorism Confinement Center.

Jhoanna: And there we got alarmed, we got alarmed because he never went so many days without communicating. And so we said: something’s happening.

Silvia: I imagine you had heard about CECOT. Did you perhaps have an idea?

Jhoanna: I had already heard about Guantanamo before. I had already heard of Guantanamo, I had already had a conversation before with my sister and I had told her: “Caro, how’s the situation with the boy going? I’m very worried because they’re sending Venezuelans to Guantanamo.” Even my sister’s wife, a son of her coworker, they had him in Guantanamo and he’s Venezuelan. So I tell her, “Caro, this isn’t very far from us, we have to be, I mean, very aware and talk to the lawyer to see what can be done, because it is happening.” And my sister would tell me: “No, relax, Jhoanna, don’t worry, the boy is in an asylum process and when they’re in an asylum process it’s impossible for them to deport them. Don’t worry.” So I told her, “ah, well, perfect, that’s very good.” And she would tell me, “don’t worry, because the boy already has his final hearing on April 1 and well, everything in his process has gone well, and we have faith that his asylum case will be favorable.” So I told her, “well, perfect.” That was before.

Eliezer: Before the United States illegally deported hundreds of Venezuelans to El Salvador. Before not hearing from Widmer for several days, knowing they had transferred him.

Jhoanna: And that’s where my sister despairs. She starts calling various detention centers because he still appeared in the system. My sister would log into the system and he still showed up as being in the Hidalgo penitentiary center. And it wasn’t until March 20, in the morning hours, that my sister managed to communicate with this number to immigration and they confirmed to her that yes, that Widmer on March 15 was deported to El Salvador. And in the afternoon is when the list comes out and we see that Widmer is first on the list.

Silvia: Jhoanna is referring to a list that CBS obtained of the names of the Venezuelans deported to CECOT. The first one that appears is Widmer.

Jhoanna: And there the pain was tremendous. It was something terrible, but I filled myself with strength. As soon as I saw Widmer’s name there on the list it was as if God had sent me a message and had told me: “There, I found him for you. He’s first on the list and he’s the first one we’re going to get out.”

Jhoanna: I don’t know how to explain it, but seeing his name there allowed me to take action. Because I was with my hands tied, because I was looking for him and couldn’t find him. Who could I sue, who could I ask for help? If I didn’t know where he was, I mean, I couldn’t take action. But, notice that not even the lawyer knew about this, because the lawyer talks to me and tells me, “but Jhoanna, it’s the first time in U.S. history that I’ve seen such a violation of rights.” He would tell me, “Jhoanna, excuse me, but I don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to do, because in more than 15 years of my career I had never in my life encountered this,” the lawyer would tell me. “I want to help you,” the lawyer would tell me, “but I don’t know how, Jhoanna.” He would tell me, “I don’t know how.”

Eliezer: After the break, Jhoanna goes to El Salvador to look for her nephew. We’ll be right back.

Silvia: We’re back on El Hilo.

Jhoanna: The only thing we knew about Widmer was that he was in that place because he led the list. We had never seen him again in any video, in any photo. I wasn’t certain that the boy was there. We started contacting organizations, we started working together with his lawyer, and all actions began to be taken, so that his innocence would be proven. At first it seemed like we were invisible, but nevertheless we never, never, never lost faith and we took action. As for the actions, there were many.

Eliezer: For example, in early May, they filed a complaint arguing that Widmer’s right to due process had been violated. A judge in Texas in mid-May ordered the Trump government to confirm where Widmer was and guarantee access to his lawyer. It was the first judicial order of that type.

Jhoanna: The American government was given a 24-hour period to give us an answer and to this date the American government completely ignored this order.

Silvia: The relatives of other Venezuelans deported to CECOT also mobilized during those months to try to get them out. They filed lawsuits before the Constitutional Chamber in El Salvador, before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. They created a committee in Caracas to organize themselves.

Jhoanna: That committee was formed by various families, but for us from Táchira it was very far away. We couldn’t attend meetings, we couldn’t be so fully involved in all this. A lot of information was getting away from us, well, because we were so far away. So, we found ourselves in the need and obligation to create another committee, but only with those from Táchira state and with the help of Dr. Walter Márquez. He’s a former Venezuelan ambassador and also the president of the El Amparo organization.

Eliezer: The El Amparo Foundation defends human rights. Walter Márquez is a historian and was a deputy in the National Assembly. He helped them create the Committee of Families of Tachiran Venezuelans Arbitrarily Deported to El Salvador.

Jhoanna: And that’s where we came to the conclusion that the next action would be to travel to El Salvador. Travel to El Salvador to file the lawsuits, to request a visit. Because it’s worth mentioning that just like me, there were many families who all they had of their young people was that their name was on those lists, nothing more. So we decided to start working based on that, to raise funds.

Silvia: They held raffles, sold food, and friends living outside the country sent donations. Widmer’s girlfriend in Ecuador held a raffle with her coworkers.

Eliezer: They managed to raise what they needed and traveled from June 10-13. It was a few days, but very intense.

Jhoanna: In El Salvador a formal request was made to the Penitentiary Centers Directorate, requesting that we be allowed to visit him. I traveled for Widmer, but I also traveled representing six Tachiran families, from here, where we’re from. But the struggle was for the 252 Venezuelans, only that due to life circumstances, due to external issues, we could only carry a power of attorney made up of six people. And it was that we be allowed to have a visit and that we be given proof of life. To this date we haven’t received a response. A lawsuit was also filed, also formally with the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office, stating all the rights that had been violated for them. So far we haven’t received information either.

Silvia: They also visited the Red Cross Committee, because they were very concerned about the health status of the detainees. And they asked the Catholic Church for help.

Jhoanna: I had also sent, long before contacting organizations and all this, I had sent an email to an address of the Human Rights Committee of the Ombudsman’s Office, and they responded that they were going to put me in contact with the regular channels so I could be given information. That was the only thing they responded, like they weren’t like they weren’t the channel I should approach. So I told them, “but if it’s not you all, then who?” And to this date I was also left waiting for the email that they were going to put me in contact with the ideal organizations for that. To this date I didn’t receive a response either. So, since all national avenues had been exhausted, well, we started taking action toward international avenues for the international complaint before The Hague. Right? Suing the entire chain of command of El Salvador’s president: from whoever opens the door of that place, to whoever closes it. His entire chain of command. Because indeed no one was responding to our call.

Eliezer: Salvadoran authorities also haven’t responded to about 70 habeas corpus petitions that lawyers filed during these months. Habeas corpus is a legal procedure that guarantees that detained persons can appear before a judge.

Silvia: The Salvadoran organization Cristosal was accompanying the families from the beginning, with psychological and legal help. They created a platform so relatives could add data about the detainees. This served to document the cases. Cristosal worked with the relatives to leave a record that refutes much of the false narrative, like that they were members of the Tren de Aragua. Cristosal also requested official information, which was denied each time.

Eliezer: They also put the relatives in contact with organizations of Salvadoran victims of the state of exception regime. These groups publicly supported the Venezuelans and their relatives. They found a common cause: freeing those who have been detained arbitrarily and illegally in El Salvador.

Jhoanna: Cristosal supported us a lot. Not only me, many Salvadorans, and at this moment my heart fills with sadness reading publicly the statement they made that they had to abandon El Salvador.

Eliezer: Cristosal had to leave the country after 25 years of human rights defense work. This is an organization that has investigated and documented corruption in Bukele’s government. Also violations like torture, abuse and deaths in prisons under the state of exception regime that has now lasted more than 3 years.

Silvia: Police detained Cristosal’s anti-corruption director, Ruth López, in May. Ruth was the lawyer in charge of the team that accompanied the families of the Venezuelans deported to CECOT to prepare and file the habeas corpus petitions. She worked very closely with them. Jhoanna’s committee published a letter condemning her kidnapping and detention.

Eliezer: Then, in June, the Foreign Agents Law went into effect, which prohibits organizations that receive funding from abroad from doing political activities, and requires them to pay a 30% tax. On their X account Cristosal explained they were suspending their operations in El Salvador given, I quote, “the escalation of criminalization.” They continue working from Honduras and Guatemala.

Silvia: Cristosal’s director, Noah Bullock, told me they built relationships of great trust with more than 160 families. Now they’re helping to document testimonies of torture and mistreatment that the Venezuelans received in CECOT: isolation, beatings, psychological abuse. Noah says what they’ve heard so far shows systematic practices. The clearest example is hearing the Venezuelans say that CECOT’s director warned them they had entered hell, that they weren’t going to get out. Because that reveals the intention to dehumanize, to punish. It shows it’s not a penitentiary system that obeys the rule of law, Noah says.

Eliezer: Noah also told us that the lack of response to the habeas corpus petitions by El Salvador’s Constitutional Chamber shows that the justice system operated for impunity and in service of the regime, instead of protecting people, as it should, and he emphasized that the fact that hundreds of Venezuelans were disappeared in a maximum security penal center, without trial, without defense, was possible because Bukele has dismantled the country’s democratic system. The Venezuelans deported to CECOT weren’t “detainees,” Noah says, they were hostages.

Silvia: And how did you feel? I don’t know if you remember how you felt returning after that visit to El Salvador. Did you feel like: OK, this is moving, there’s hope.

Jhoanna: Yes, I, I came back full of great hope. I traveled with the hope of seeing him, of course, but deep in my heart I was also like there’s the possibility they won’t let me see him. But, the actions I’m taking have a lot of power, they have a lot of weight and I know they’re going to set a lot of precedent for future actions.

Eliezer: El Amparo, the foundation the Táchira families have been working with, is preparing a lawsuit before the International Criminal Court against Bukele and other members of his chain of command. Other organizations started the process to sue the United States on behalf of one of the Venezuelans deported to CECOT.

Jhoanna: The three days I was there I didn’t sleep, drafting each one of the documents that were filed, reading the Salvadoran Constitution, seeing which articles I could rely on, but I came back satisfied because I knew, Silvia, that each one of my actions and each one of the actions each family took were going to have results. Maybe not immediately, Silvia. But I knew that each action had a fabulous result and everything was adding up. And yesterday, having my boy with me, I realised that yes, that everything added up.

Silvia: We’ll be right back.

Eliezer: We’re back on El Hilo.

Silvia: How did you find out they were going to return him to Venezuela? Tell me about that moment.

Jhoanna: Oh, I found out on Friday at 7:00 in the morning. I got a call from my friend Elizabeth. She’s from the committee. We’ve become very, very good friends. And she was telling me, “Jhoanna, did you see the news?” “No. What happened?” “Check, check your phone,” she was shouting. And I: “Hold on, hold on. I don’t understand anything.” And I see all these news stories that an exchange had been made, that there was a negotiation. But since we had gotten our hopes up before with something similar, I’m, as we say here, very impulsive. So, I said hold on Jhoanna, calm down, let’s wait.

Eliezer: She sent a message to Gris Vogt, a Mexican-American woman who had been helping the families.

Jhoanna: And at 11:00 in the morning Gris responds to my message and tells me, “Jhoanna, it’s real.” My soul returned to my body. I started calling my family happily, telling them: “The boy is coming, the exchange was made.” My brother was telling me: “Jhoanna, are you sure?” I told him, “Yes, yes, I’m sure. Gris told me yes.” When I call my sister and tell her: “It’s real, Carito, it’s real.” No, it was really wonderful. Never, never, Silvia. Never had my heart experienced that emotion.

Silvia: Jhoanna wanted to go to Caracas to receive Widmer. But those from the general Committee of relatives, the one in the capital, told those who live far away not to travel, that the authorities would deliver each of the repatriated to their house door.

Jhoanna: So I said well, I’m going to wait for him. I live in Colombia, I came immediately to Venezuela, and waited thinking: the food, what food are we going to prepare for him, what will he want to eat. The neighbors: “What time does he arrive? We want to receive him.” And so we started from Friday: no, he arrives today; no, tomorrow; no, the day after, because they were always delayed. We always live far from the center of the country and the great day arrived. The agents who were bringing them, from Venezuela’s National Guard, communicate with my sister-in-law and tell her they’re coming, to wait for them at the house door, to have Venezuela’s flags, the banners, to receive him as we had already planned it, but that they’re coming. Since the whole community was already here we organized and then, where we live there are two ways to arrive. We were uncertain: Which of the two ways will he arrive? The motorcycle riders were waiting for him.

They went to wait for him on the main road. All the motorcycles had horns. His dad went to receive him there. Those cars are recognizable, because since we had already seen the videos of the other families, we already knew which car it was. And when they come up, the boy tells me that he sees all that and that his companion was telling him, “but who are you? Who are you? Why are all those people there?” And he was saying, “No, I don’t know, I don’t know what’s happening. They’re from my community.”

They all came in a caravan and escorted him. They accompanied him until arrival. The formal protocol was that they should get him out, deliver him at the house doors and into his relative’s hands, but the people bringing him didn’t imagine there were going to be so many people. And they were telling Widmer, “But hold on, where do we get out. There are a lot, a lot of people. What do we do?” So, he told them, imagine me being a little chubby, and the boy told them, “that chubby lady coming there is my aunt, she’s my aunt.”

When they opened the door, I was there waiting for him. My boy was also anxious for them to open that car door and as soon as they opened the door, the first thing I saw were his extended arms. His bright little eyes, his beautiful smile. And he extends his arms to me and hugs me and tells me, “Aunt, relax, I’m here now. I’m fine, I’m fine. I love you,” he was telling me.

My little one!

Widmer: Everything’s fine, thank God I arrived… Everything’s fine, everything’s over now. Thank God.

Silvia: After Jhoanna told us about this moment, the call cut out. There was a blackout. “Welcome to Venezuela!” she told me an hour later. The power had already gone out earlier. Through WhatsApp, a few days before closing this episode, she told me that Widmer is enjoying the simplest things: every bite of food, watching a movie, going out and feeling the sun. She says he wants to focus on barbering as a new chapter to channel his energy and creativity. He has all his family’s support. And Jhoanna says that seeing him happy and fulfilled is the greatest reward.

Eliezer: After the exchange and liberation, the governments of the three countries have been trying to gain political advantages. Venezuela’s Interior Minister, Diosdado Cabello, said they had gotten them out of hell in exchange for the liberation of “murderers.” As we told you two weeks ago, in Venezuela there are more than 800 political prisoners. They torture in the country’s prisons and there are people who have died from that mistreatment.

Silvia: The exchange has also served Bukele to continue with his narrative. He repeated that many of the liberated Venezuelans face serious crimes, although we already know that the majority had no criminal record. You might remember that Bukele had proposed an exchange of the 252 for the same number of political prisoners in Venezuela. The following month, they detained Ruth López, the Cristosal lawyer who had denounced multiple corruption cases in Bukele’s government. In El Salvador there are also political prisoners. Until March of this year, the Committee of Families of Political Prisoners and Persecuted had registered 28 cases.

Eliezer: And in a statement, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio celebrated that, I quote, “every American unjustly detained in Venezuela is now free and back in our homeland.” At the same time, his government continues detaining migrants without records, tourists who are passing through, foreign students who participate in protests, and people who comply with the requirement to go to an immigration court to regularize their situation in the country.

Silvia: This episode was produced by me, with help from Mariana Zúñiga and Gabriel Labrador. Eliezer edited it. Bruno Scelza did fact-checking. Sound design and music are by Elías González.

The rest of El Hilo’s team includes Daniela Cruzat, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El Hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask you to join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to go deeper into today’s episode, subscribe to our email newsletter by going to elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it every Friday.

You can also follow us on our social media. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook and Threads. You can find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share the episodes.

I’m Silvia Viñas. Thanks for listening.