Cuba

Parole humanitario

Migración

Donald Trump

Deportación

Ley de ajuste cubano

Lazaro Yuri Valle Roca

El Gobierno de Donald Trump está cerrando los caminos legales para migrar a Estados Unidos. El más reciente es el parole humanitario. A finales de mayo, la Corte Suprema dio luz verde para cancelar esta protección temporal a más de 500 mil haitianos, cubanos, nicaragüenses y venezolanos. En este episodio nos enfocamos en el caso de los cubanos, que enfrentan un desamparo drástico. Laura Rojas Aponte, productora de Radio Ambulante Studios, nos cuenta sobre Lazaro Yuri Valle y Eralidis Frómeta, una pareja de periodistas perseguidos que migraron con parole. Luego, la periodista cubana Carla Gloria Colomé nos explica la situación de más de medio millón de personas que no pueden acceder a la vía legal que, durante décadas, permitió a los cubanos radicarse en Estados Unidos. Y, para poner este panorama en perspectiva dentro de la política migratoria de Trump hablamos con María José Espinosa, directora ejecutiva del Centro para la Colaboración y la Incidencia en las Américas (CEDA).

Inscríbete aquí a nuestro Club de Escucha Virtual en alianza con CEDA.

Este episodio fue realizado gracias al apoyo de CEDA, una organización que reúne a gobiernos, sociedad civil y comunidades de las Américas para promover políticas que mejoran el bienestar y respetan la dignidad y los derechos de las personas en todo el hemisferio.

Créditos:

-

Reportería

Laura Rojas Aponte -

Producción

Silvia Viñas, Laura Rojas Aponte -

Edición

Eliezer Budasoff, Daniel Alarcón -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción en redes sociales

Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elias González -

Música

Elias González, Remy Lozano -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

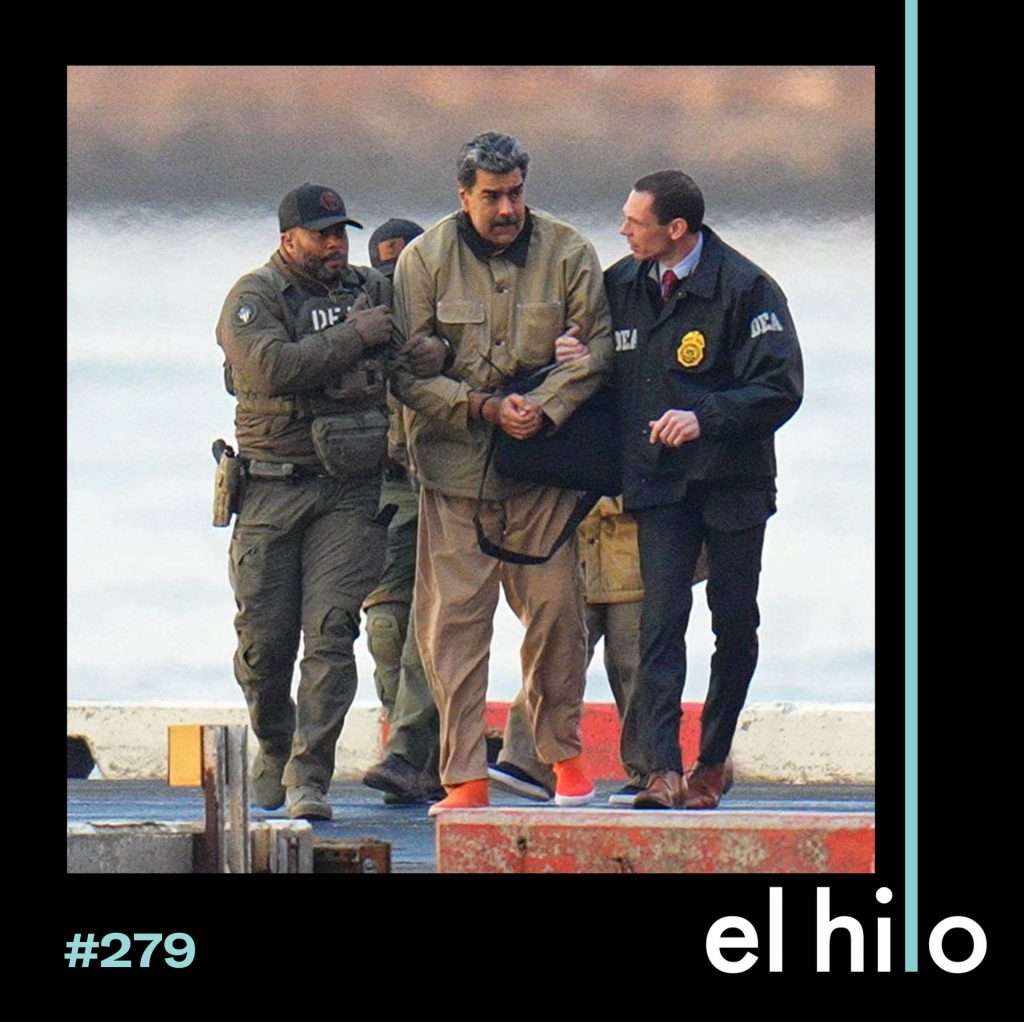

Fotografía

Getty Images / John Lamparski

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Eliezer Budasoff: Este episodio fue realizado gracias al apoyo de CEDA, una organización que reúne a gobiernos, sociedad civil y comunidades de las Américas para promover políticas que mejoran el bienestar y respetan la dignidad y los derechos de las personas en todo el hemisferio.

Silvia Viñas: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un pódcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: Y yo soy Eliezer Budasoff.

En su primer día de vuelta en la Casa Blanca, Donald Trump firmó una orden ejecutiva que terminaba con el parole humanitario.

Silvia: Es una figura legal que diferentes gobiernos han usado durante décadas, y más recientemente la implementó Joe Biden. Le daba un permiso de permanencia temporal a personas que no cumplían con los requisitos para tener una visa, pero podían entrar a Estados Unidos por razones humanitarias.

Eliezer: Más de 500 mil haitianos, nicaragüenses, venezolanos y cubanos llegaron a Estados Unidos con este permiso.

Silvia: En enero también salió a luz un memorándum del Departamento de Seguridad Nacional que decía que autorizaba las deportaciones expeditas de personas con parole. Y aunque una jueza bloqueó la orden de Trump en abril, a finales de mayo.

Audio de archivo, presentador: La Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos ha decidido poner fin al programa de parole humanitario.

Audio de archivo, periodista: Y lo que escribió la magistrada Jackson es contundente. Dijo que la corte no tomó en cuenta las consecuencias devastadoras que esta decisión podría tener en las vidas de miles de migrantes que tienen casos pendientes.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: El Departamento de Seguridad Nacional notificará a cientos de miles de inmigrantes que su permiso para vivir y trabajar en Estados Unidos ha sido revocado y que deben abandonar el país.

Eliezer: Hoy, qué pasa cuando la promesa de migrar con un camino legal se disuelve, en qué situación quedan las personas que huyeron de países en crisis. Y qué nos dice este cambio sobre la definición del gobierno de EE. UU. de quién merece protección y quién no.

Es 20 de junio de 2025.

Silvia: Laura, tú has estado reportando para El hilo sobre los migrantes cubanos y su situación, que es particular, pero tampoco es única. Hace unas semanas la Corte Suprema le dio luz verde a la administración de Trump para terminar con el parole humanitario, y sabemos que había miles de cubanos que llegaron a Estados Unidos con este parole. Entonces, para empezar, nos gustaría que nos cuentes en términos generales cuál es la situación de estos migrantes ahora.

Laura: Pues lo que yo encontré es que estamos hablando de una orden ejecutiva, que deja a más de 100.000 cubanos en una situación de incertidumbre.

Eliezer: Ella es Laura Rojas Aponte. Es colombiana pero ahora vive en Nueva York, y es productora para Radio Ambulante Studios.

Silvia: Los cubanos a los que se refiere llegaron a Estados Unidos escapando de una profunda crisis en la isla.

Laura: Migran a Estados Unidos con una medida que se llama parole humanitario, pensando en atender a gente en situaciones urgentes y extremas, y llegan a Estados Unidos con este documento. Y con la orden ejecutiva y la cancelación les están diciendo “ya no tienes ese documento”. Entonces estos cubanos quedan en situación de indocumentados, su estatus legal cambia y ahora son personas que también son deportables.

Silvia: Tú hablaste con personas que están, con cubanos que están como en este limbo ahora mismo. ¿Cuéntanos a quién conociste?

Laura: Claro, porque estoy tratando de entender qué está ocurriendo con estos miles de cubanos en Estados Unidos. Y me encuentro con un colega, con Lázaro Yuri.

Lázaro Yuri: Me llamo Lázaro Yuri Valle Roca. Soy periodista independiente. También he sido activista de derechos humanos.

Laura: Y veo que su caso me permite entender muchas de estas políticas que son tan abstractas. Encuentro que Lázaro vino a Estados Unidos hace un poco menos de un año y un día, que es un número importante en esta historia. Encuentro que él ha sido un perseguido. Realmente está urgido de salir de Cuba. Él, independientemente, publicaba historias de —comillas— “opresión” en un medio que se llama Delibera, y migró a Estados Unidos con su esposa.

Eralidis: Soy Eralidis Frómeta, periodista independiente.

Laura: Quien desde los 90 ha sido una activista en Cuba.

Eralidis: Es decir, dondequiera que había una actividad de la oposición cubana, ahí estábamos nosotros. Igual, además de tomar evidencia, también sacábamos un cartelito, gritábamos. Y esas fueron las consecuencias que ha traído para nuestra familia el activismo político nuestro.

Laura: Primero leo sobre su caso en la prensa. Debo decir que su nombre y su cara es familiar para varios dentro de la comunidad. Y entonces terminó viajando de Nueva York a Pensilvania.

Eralidis: Hace 11 meses estamos acá. Viviendo acá en Lancaster.

Laura: A esta ciudad que es pequeña, radicalmente distinto a llegar a La Habana.

Eralidis: Esto está más grande que lo que teníamos en Cuba. Pero este espacio.

Lázaro Yuri: Este espacio aquí está más grande. Eres un poco más chiquito. Vaya. Más o menos como de aquí allá.

Laura: Un espacio que es básicamente un rectángulo donde queda la sala, el comedor y la cocina, y un pasillo que te lleva a un baño y una habitación. Y Lázaro y Eralidis dicen que eso es un espacio mucho más grande que donde ellos vivían en Cuba, porque básicamente en Cuba ellos vivían en una habitación que tenía un espacio adyacente de cocina y social. Y además ellos recuerdan que todo el tiempo estaban vigilados por la policía especial. Cuando yo les pregunto cómo saben que es la policía especial, se burlan de mí. Obvio que ellos saben.

Eliezer: ¿Por qué tenían ambos la urgencia de salir de Cuba?

Laura: Ellos han sido víctimas de la represión desde la manera como se casaron. Yo llego a la casa y rápidamente les pregunto: ¿desde hace cuánto son pareja?

Lázaro Yuri: Nos casamos estando yo en prisión.

Laura: Pero Eralidis corrige: pero llevamos 15 años juntos.

Eralidis: Pero, bueno, realmente llevamos 15 años de matrimonio, pero bueno, legalmente, lo legalizamos estando él en prisión.

Laura: También, hace más o menos 11 o 13 años Eralidis quedó embarazada de Lázaro.

Eralidis: Tuviéramos un hijo ya de unos 11, 12 años. Pero en una represión, la policía política me dio una golpiza hasta perder el bebé.

Laura: Y dice: “No le he podido dar hijos a mi esposo”. Pero Lázaro le corrige: “Bueno, pero tus hijos de tu matrimonio anterior es como si fueran míos”.

Lázaro Yuri: Y los nietos son preciosos y me quieren y me dicen abuelo y los quiero igual.

Laura: Eso es como un principio. Pero por otro lado, Lázaro llega acá directamente, básicamente directamente de la cárcel.

Hay una protesta. Esto se puede ver en YouTube.

Audio de archivo, protesta octavillas: 2021, conmemorando un aniversario más del natalicio de nuestro Titán de Bronce, un grupo de activistas.

Laura: En el que Lázaro sube al último piso de un edificio en La Habana, de esos edificios que son coloniales, que están caídos, y empieza a lanzar papeles contra el régimen.

Audio de archivo, protesta octavillas: tenía pensamientos de José Martí.

Laura: Y eso no le gusta a la policía especial.

Audio de archivo, protesta octavillas: recogían los mensajes, pero la policía con perros obligaban a los transeúntes a botarlas.

Laura: Más adelante, Lázaro va a una protesta donde la policía especial lo captura y lo amenaza.

Lázaro Yuri: Y entonces ahí me dicen que yo tengo que renunciar a mis ideales y a seguir haciendo periodismo, y de renunciar a mi organización y todo ese tipo de cosas. Yo les digo que no.

Laura: Y le dicen: “Usted tiene que comprometerse a dejar de hacer periodismo o va a sufrir las graves consecuencias”. Dice que no, y las graves consecuencias es que lo capturan y lo envían a la cárcel.

Lo sentencian a cinco años por propaganda. Pero cuando tú miras su caso, no es claro si eran cinco años, seis años. Lo envían a una cárcel de máxima seguridad donde él dice que había asesinos, que había personas con crímenes graves, como violaciones. Entonces tampoco es muy transparente cuál fue su proceso legal. Lo cierto es que termina en la cárcel y él narra la hipervigilancia típica de un preso.

Lázaro Yuri: Desde que entras a la prisión no puedes dormir, no puedes aceptar nada de nadie. Tienes que estar pendiente de que te están mirando, de lo que te están haciendo, porque están pendientes mucha gente, entonces.

Laura: Es como: no puedes dormir, estás rodeado de gente que no conoces, pero que sospechas que no son buena compañía. Ir al baño es difícil, no puedes comunicarte.

Lázaro Yuri: Date cuenta que no podía ni hablar por teléfono, porque estaban grabando y estaban escuchando. Esconderme para poder escribir.

Laura: Él igual es periodista, tiene la pulsión de comunicar lo que está pasando. Entonces escabulle notas y escritos para su esposa. Y de vez en cuando su esposa lo visita, sus hijos lo visitan, sus nietos lo visitan. De vez en cuando sí come, empieza a enfermarse, le dan forúnculos en la nuca, tiene problemas estomacales, tiene problemas en la piel. En una cárcel vivió una experiencia espeluznante en donde lo amarran acostado, lo acuestan en una camilla y lo meten horizontalmente.

Lázaro Yuri: ¿Tú has visto una morgue? Bueno, que te pongan a ti, que tú no eres muerto, en una bandeja así. Y entonces tú no puedes moverte. Entonces tú, acostado ahí, te meten hacia adentro como si fuera una gaveta así de una morgue. Y entonces una gota de agua que te va cayendo en la frente. Constante. Constante. Constante. Constante.

Laura: Y cuando te sacan, es para ponerte aire acondicionado en la cara. Y luego te vuelven a meter ahí.

Lázaro Yuri: Torturas psicológicas y físicas y degradantes, porque te están degradando moral y espiritualmente.

Laura: En esa situación, él decide no recibir comida y no recibir agua.

Lázaro Yuri: Entonces todas esas cosas, imagínate tú, y que yo empiece a convulsionar ahí adentro de la cosa esa, porque yo estuve cinco días sin tomar agua.

Laura: Su hija los convence: “ustedes tienen que irse de Cuba porque esto ya es un tema de vida o muerte.”

Lázaro Yuri: Sí, es verdad. Y además, yo no quería venir. Quien me convence a mí es la niña, que llorando me dice: “Papá, tú tienes que irte porque yo no te quiero muerto”.

Eliezer: Después de la pausa, Lázaro y Eralidis logran salir de Cuba. Ya volvemos.

Silvia: ¿Alguna vez has escuchado un episodio de El hilo y has sentido que quieres conversarlo con alguien?

Te invitamos a unirte a un Club de escucha para charlar sobre el tema del episodio de hoy con nuestro equipo el próximo miércoles 25 de junio.

Nos acompañarán la productora de este episodio, Laura Rojas Aponte, María José Espinosa, directora ejecutiva del CEDA, y Daniel Alarcón, director editorial de El hilo y presentador de Radio Ambulante.

En la descripción de este episodio puedes encontrar el enlace para inscribirte. También está en nuestra página: elhilo.audio.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo. Eralidis se enteró sobre el parole humanitario por uno de sus hermanos, que ya estaba en Estados Unidos. Él, de hecho, fue su patrocinador, o sponsor, que es un requisito para conseguirlo.

Eliezer: Diplomáticos y ONGs también los ayudaron. Eralidis dice que hicieron la solicitud de parole en febrero de 2023. Y se lo aprobaron bastante rápido. Dejaban que Lázaro saliera de la cárcel para hacer los trámites. Siempre custodiado. Lo que se demoró más fue el permiso para irse de Cuba.

Laura: Eralidis, en un acto de desesperación, va a la embajada de Estados Unidos y los funcionarios le dicen: “Bueno, te vamos a ayudar a gestionar el permiso”. Ella no sabe qué ocurre, pero una semana después tiene su permiso de salida. Entonces, lo que ella me está narrando es unos funcionarios estadounidenses intercediendo ahí. Pero básicamente es un año de espera.

Eralidis: El día 4 de junio lo sacaron a él de la prisión. A mí me fueron a buscar a mi casa, custodiada, como serían las dos de la tarde. Llega el de la policía política, me dice: “Eralidis, recoge la ropa del viaje de Lázaro”.

Laura: Desde la perspectiva de Lázaro, él está enfermo. Está en la cárcel. Un día lo llevan a una clínica, lo esposan a una camilla de una clínica.

Eralidis: Esposado como un criminal, como un criminal. De pies, manos, cintura.

Laura: Él dice que le ponen una sonda. Lo repitió varias veces. Y le permiten hablar con su esposa. Y ahí se entera de que se va a Estados Unidos.

Lázaro Yuri: Al otro día por la mañana me levantaron y me dijeron: “Dale, que te vas, rampampam”.

Laura: Cuando yo te cuento lo que él vivió, suena como una noticia positiva, pero también, como alguien que emigró a este país, yo lo veo como algo extraño. Porque cuando tú estás migrando te preguntas: ¿qué echo en la maleta, no? ¿Qué fotos llevo, de mi familia? ¿Mi libreta de apuntes? Yo qué sé. Entonces, esas preguntas típicas que uno se hace cuando sabe que su vida va a estar en otro país, para él no existió. Su esposa empaca maletas por dos personas y luego, una noche en la clínica, al otro día en el aeropuerto.

Lázaro Yuri: Me llevaron hasta el aeropuerto, me dejaron ahí y fui caminando hasta allá, hasta donde estaba Lily, y ya había otros oficiales y otros militares ahí, vestidos de civil.

Laura: Los custodian hasta el aeropuerto, hasta el avión. Ellos describen que un agente de la policía especial abordó con ellos y solo hasta que estaban en el aire le permiten levantarse del asiento.

Silvia: ¿Y cómo están? ¿Cómo les va en Estados Unidos?

Laura: Inicialmente llegan a vivir con su hermano, con su familia, y luego dicen que necesitan independizarse. Entonces se van a este apartamento donde yo los conocí. Parte de la —comillas— “humanidad del parole humanitario” es que te da un permiso de trabajo. Entonces tú llegas a un lugar y puedes empezar a ganarte tu sustento. Y también esa es la tragedia de cancelar el parole humanitario: que entonces le estás quitando también la posibilidad a las personas de ganar dinero y subsistir. Encontraron trabajo en una fábrica de sopas unos meses. Eso se acabó. Eralidis, por medio de un grupo de Facebook de cubanos en su ciudad, logra esta chamba en un hotel. Y Lázaro no, está desempleado. Y ha estado recuperándose.

Lázaro Yuri: Yo entré con 50 libras. Imagínate tú, 50 libras de peso. Era hueso y pellejo nada más, como decimos nosotros.

Eralidis: Si él no hubiera salido de Cuba, él a esta hora probablemente ya no estuviera ni vivo, no estuviera ni sentado ahí contando la historia, porque él estaba más muerto que vivo. Ya él llegó aquí a los Estados Unidos muy, muy desgastado, muy débil.

Laura: Lázaro aún es una persona delgada. Lázaro ha estado yendo a citas médicas sistemáticamente. Entonces yo entiendo que el trabajo es crucial para la subsistencia. Y también estoy frente a una persona que también está, como, en otros procesos de salud.

Silvia: ¿Y cómo se enteran del fin del parole humanitario?

Laura: Eralidis recibe una notificación en su teléfono, lo abre y, para toda mi sorpresa, le causa gracia.

Eralidis: Inmediatamente le digo: “Valle, mira esto. Oh, estamos en Cuba”. Y la reacción de él inmediatamente fue: “Si nos deportan, nos tiramos del avión en Cuba gritando ‘¡Abajo la dictadura!’”.

Lázaro Yuri: “¡Abajo la dictadura!” Y vamos de frente para ellos. Y que me, y ahí que me maten pal diablo ya y ya. Y ya salí de eso porque ya me quitó toda esta.

Eralidis: Yo dije: “Ya nos van a mandar para Cuba. Imagínate tú”.

Laura: La notificación dice, está suspendido el parole humanitario.

Lázaro Yuri: Esta es la mía: Parole Termination.

Laura: Ellos reciben la notificación y se enteran de que su documentación para estar legal en este país se va a terminar. Y eso claro que es un golpe, pero es un golpe doble, porque ellos están procurando que otras personas muy importantes para ellos también vengan a Estados Unidos con el mismo parole humanitario.

Eralidis: En ese momento mi hermano ya se estaba preparando para ponerle el parole a mi hija con mis nietos, y fue una desilusión tan grande que me creó, que en un momento la decisión fue de regresarme a Cuba al lado de ella. Lo que ella misma me decía: “Mamá, no, no puedes regresar, te van a matar. No pueden”.

Laura: Y es una niña que creció en represión. Es una niña a la que la policía especial le hackeó el teléfono y le envió fotos sexuales cuando tenía 12 años para martirizar a sus padres. Es una niña que también, bueno, una niña que creció a ser adulta y que luego su hijito va a ir a visitar a su abuelo a la cárcel, consciente de que está creciendo en una isla con profundas injusticias.

Entonces ellos quieren reunificarse, por como la pura necesidad humana de estar cerca de los tuyos. Pero también esa es otra generación, y otra generación que necesita salir de la crisis, y el parole humanitario les trunca el camino.

Eralidis: Desafortunadamente, no podemos tener la familia completa aquí. No pudimos.

Laura: Y esto se pone más agudo aún, porque entonces vemos que la primera semana de junio, Donald Trump anuncia una prohibición de viajes, el travel ban, a 19 países distintos, incluido Cuba. Y entonces ellos ahora ni siquiera van a poder tramitar una visa de turismo. El parole humanitario era uno de varios caminos que tenían Eralidis y Lázaro para reunificarse con su familia, que se cerró, pero todos se van cayendo uno a uno.

Entonces la pregunta para ellos es: ¿hasta cuándo, no? ¿Cuándo voy a poder abrazar a mi nieto?

Eralidis: De la forma que nosotros fuimos, que nos sacaron de Cuba, ¿no? A pesar de haber venido con un parole, yo no tengo la seguridad de que me van a dejar volver a Cuba a ver a mis dos hijos, a mis nietos. Mi madre, que también está allá.

Laura: Los deja, como a tantos migrantes, con la pregunta de: ¿ahora qué voy a hacer? Entonces ellos, pues igual, tienen que resolver su situación. Ya hablaron con su abogado y están solicitando asilo político.

Cuando definitivamente cancelaron el parole humanitario, cuando la Corte Suprema les dijo: “Sí, vamos a aprobar esta cancelación”, Lázaro me envió una nota de voz.

Lázaro Yuri: Bueno, Laurita, imagínate tú. Tú sabes que, es una incertidumbre tremenda la que tenemos nosotros y estamos esperando, por lo menos en el caso…

Laura: Y luego, frente a las noticias de las prohibiciones de viaje, yo le pregunté qué opinaba y me decía: “Seguimos esperando”. Y esta mañana, antes de conversar con ustedes, yo le volví a escribir a ver cómo estaba, y me dice: “Seguimos esperando”. Entonces yo siento que estamos con unos cubanos que están esperando su parole humanitario, esperando su permiso de salida, esperando a ver qué hace el gobierno de Trump cuando quita opciones, esperando a ver cómo se resuelve la situación, esperando la demanda, esperando, esperando, esperando. Y mientras tanto, es como que no puedes echar raíces en esta nueva tierra a la que llegaste.

Entonces yo me despido de ellos y quedo con esta sensación de: qué situación tan imposible, qué decisión tan difícil. No puedes regresar a la isla, claramente. Y las maneras de establecerte acá no se sienten concretas.

Silvia: Pero esta no es la única vía legal que se está cerrando para los cubanos, ¿cierto?

Laura: Y ese contexto más grande es lo que a mí me ha consumido semanas de reportería. Porque entonces, si tú te paras en la perspectiva de un cubano que quiere emigrar a los Estados Unidos, se abren distintas opciones para hacerlo. Tantas opciones como el sistema migratorio de Estados Unidos, que es complejo y lleno de caminos. Entonces un camino es el parole humanitario. También puedes pedir una visa regular, digamos, una visa de turismo. Te toca hacerlo en otro país. Pero también, y creo que esto es lo que más tenemos presente de las noticias, puedes cruzar fronteras. Ellos le dicen “brincar fronteras”. Entonces brincas fronteras de un país a otro, ta ta ta, llegas a México para cruzar a Estados Unidos. Ahí te encuentras con un agente migratorio y te puede dar dos formularios que son los míticos I-220A, I-220B.

Y esto solo le agrega complejidad al asunto, porque estos dos formularios son, –comillas– muy grandes, documentos de deportación. Uno que te pueden entregar mientras tu proceso de deportación está en curso y el otro cuando ya tienes una orden de deportación. El formulario I-220A lo tienen aproximadamente medio millón de cubanos. No es claro ni para los grupos de activistas, ni para los abogados, ni para los mismos cubanos, por qué unas personas reciben un formulario u otro. Nadie sabe. Lo que sí sabemos es que, dentro de una misma familia cubana, una persona puede tener el parole humanitario, otra persona puede tener un formulario I-220A, otra persona puede recibir un formulario I-220B. Otra persona puede haber tenido una visa de reunificación o de turismo o de estudiante.

Carla Gloria Colomé Santiago: Quizás por primera vez tú estás viendo en una misma familia a personas ciudadanas conviviendo con personas que pueden estar a punto de ser deportadas.

Laura: Para entender mejor esto hablé con Carla Gloria Colomé Santiago, una periodista cubana también establecida en Nueva York. Carla cubre las historias de cubanos y otras comunidades hispanas dentro y fuera de la isla.

Carla Gloria Colomé Santiago: Y eso está creando grandes conflictos familiares, grandes conflictos como comunidad. Una comunidad que, los sociólogos lo han dicho, los historiadores lo han dicho, no está ni preparada para lidiar con esto.

Laura: Las personas que tienen este formulario también están en una situación de incertidumbre, igual a quienes quedan con un parole humanitario interrumpido. Entonces, lo que yo veo es que estamos hablando de aproximadamente 600.000 personas que vienen de Cuba buscando su futuro en Estados Unidos, reciben distintos caminos legales. La administración de Trump cierra estos caminos y ellos, de nuevo, quedan como suspendidos en el aire, a merced de lo que ocurra con las políticas públicas acá.

Carla: En un limbo legal que no se sabe, básicamente, lo que va a pasar. Tienen diferentes categorías migratorias, pero que les impide el camino a acceder a este privilegio de la Ley de Ajuste Cubano. En 1966 nace una ley que es la llamada Ley de Ajuste Cubano, que es la ley con la que por años, decenas y decenas de generaciones de cubanos han llegado a los Estados Unidos y han podido regularizar su estatus migratorio.

Laura: En una frase: es una ley que permite eventualmente obtener tu ciudadanía estadounidense. Nació algunos años después de la Revolución cubana, justamente para ofrecer un camino especial, más directo, a las personas que huían del régimen comunista.

Carla: Básicamente te garantizaba una protección. Si tú tienes una visa, una visa de turismo, una visa de estudiante y demás, llegas al país de manera legal, tú puedes al año y un día aplicar a la Ley de Ajuste cubano y aplicar a tu residencia. Tú entrabas al país, tú podías beneficiarte con bonos, con los food stamps, con seguros médicos y demás, y vivías todo un año con este tipo de ayudas y podías acceder a permiso de trabajo, en algún sentido, protegido. Y luego, al año y un día, cuando tú permanecías en Estados Unidos un año y un día, tú podías entonces aplicar a la llamada Ley de Ajuste Cubano. Por eso la comunidad cubana, en su mayor medida, es una comunidad legalizada. Ese es el llamado “privilegio cubano” con respecto a otras comunidades que no lo tienen.

Ahora, por primera vez, lo que está pasando es que ese llamado privilegio podría estar peligrando. ¿Por qué? Porque nunca en la historia de la emigración cubana hacia Estados Unidos ha habido tantas personas a la vez en una completa ilegalidad, en un limbo legal, viviendo con tanta incertidumbre como ahora.

Hay muchísima gente viviendo con miedo. En Miami, que es una ciudad donde el accidente está a la orden del día, muchísima gente con miedo a tener un accidente. Con miedo a veces… o sea, como: “Dale, vamos, yo voy al trabajo porque tengo que trabajar, pero rápido viro”. No todo el mundo ya te digo, es una comunidad con mucha gente legalizada, pero las personas tienen miedo. Estamos viendo casos y estamos viendo cada vez más que esto que pensábamos que no nos iba a pasar a nosotros es cada vez más una realidad. O sea, ¿quién iba a imaginarse una madre cubana deportada a la isla y dejando detrás a su hija de apenas dos años, o casi dos años, con el padre?

Laura: Carla me habla de Heidy Sánchez. Cruzó fronteras, llegó acá, recibió un formulario I-220B.

Carla: En algún punto estaba tratando de regularizar su estancia acá porque su esposo es ciudadano americano, y en algún momento iba a pasar. ¿Qué pasa ahora? Que bueno, nada: es un estatus que básicamente es casi una orden de deportación expedita, y te tienes que ir del país.

Laura: En su cita de la corte la deportan. Termina en Cuba, y ella le dice a la prensa: “Miren, tengo el alimento de mi bebé aquí en mis pechos, y mi bebé está en Estados Unidos con mi esposo”. Este caso, por supuesto, despierta todo tipo de visceralidad en la comunidad y se vuelve un poco icónico de la crueldad de estas políticas. Y cómo: ¿hasta dónde vamos a llegar para cumplir con nuestra cuota de deportación, no?

¿De verdad estamos dejando a un bebé sin alimento, a una persona que estaba yendo a la cita, como le dice la ley que haga? Ella logró la aprobación de una orden de reunificación familiar. Esto es apenas la aprobación. Le falta presentar documentos y le falta una entrevista en la embajada. Y todavía hay unos pasos. O sea, que lo que dice su abogada es que, más o menos en un año, puede quizás regresar a unirse con su familia.

Carla, reportando estas historias, va aprendiendo de los casos, pero también de la reacción dentro de la comunidad cubana. Y es algo que los deja alterados, porque es una comunidad que principalmente ha migrado legalizada. Y es una comunidad que sabe lo que es la situación difícil, pero no este nivel de dificultad. Y les aterra.

Carla: Porque el cubano, por primera vez, está viviendo esto. Siempre el camino, el camino fue muy fácil. El camino fue: “Bueno, nada, mi familia o el que pueda me acoge un año y un día. Yo mientras tanto trabajo, pero al año y un día yo tengo residencia. Ya yo puedo volver a Cuba a visitar a mi familia. A los cinco años voy a ser ciudadano. Todo bien, todo perfecto”. Y por primera vez no. Eso no es lo que está pasando. Por primera vez nos estamos pareciendo a los migrantes de todo el mundo.

Laura: Les aterra leer las historias que periodistas como Carla están publicando, porque no es algo que ellos crean que es justo o digno. Y para aquellos cubanos que, justamente por estar legalizados, pueden votar, pues los deja confrontándose con a quién apoyaron: 58 % votó por Trump.

Eliezer: Hacemos una última pausa, y a la vuelta vemos cómo cabe todo esto dentro de las políticas migratorias de Trump. Y cuál es el impacto de terminar con las vías legales para migrar. Ya volvemos.

Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Silvia: Nos gustaría poner esto en perspectiva, ¿no? Dentro de la política migratoria de la administración de Donald Trump, ¿qué argumentos tiene el gobierno para cancelar el parole humanitario y otras vías de entrada legal?

María José: El argumento fundamental es que esto ha sido un abuso del sistema de migración y de las leyes migratorias estadounidenses, cuando en realidad fue una respuesta, en el caso específico del parole humanitario a un incremento de la llegada de ciudadanos de Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua y Haití a la frontera de los Estados Unidos por diversas causas.

Eliezer: María José Espinosa es la directora ejecutiva del Centro para la Colaboración y la Incidencia en las Américas, CEDA.

María José: Un sistema que además ha funcionado. Este parole humanitario, algo que yo creo que es bastante importante es que necesitas tener a alguien que te patrocine desde los Estados Unidos, con lo cual se implica a la ciudadanía en recibir a estas personas, en asegurarse de que estas personas se integren en las comunidades, que tengan trabajo, que tengan sus papeles y que aporten a las comunidades.Entonces se movilizó, de una manera muy humana, a una ciudadanía estadounidense que decidió recibir a ciudadanos de estos cuatro países y de Ucrania. O sea, el parole humanitario comenzó con las personas de Ucrania que estaban sufriendo, o que sufren la guerra con Rusia.

Entonces, en realidad, es un sistema muy organizado que te permite saber quién entra, cuándo entra, con permisos muy específicos. El ataque yo creo que también, tiene que ver con la vilificación de la migración, con el incremento de la xenofobia, con crear un miedo al otro. Entonces creo que tiene que ver también con algo mucho más generalizado de esta política xenofóbica y de esta política racista.

Silvia: ¿Y también puede ser una manera de cumplir con su promesa de deportar de manera masiva? Porque si le cancela este estatus legal a las personas que tenían parole, significa, bueno, ahora son deportables, digamos. Y sabemos que no ha podido deportar quizás a tanta gente como él quería. Entonces, ¿nos preguntamos si también esta es una manera de hacerlo?

María José: Yo creo que eso es un buen punto. Efectivamente, hay una promesa de deportaciones masivas. Ahora, la manera práctica en la que se implementa y en la que se puede llevar a cabo una deportación es mucho más complicada.

Entonces, lo que hemos visto es que, efectivamente, como estas personas entraron a través de un programa del gobierno estadounidense, están registradas en sistemas y son como dices, deportables. Quiere decir que te puedo encontrar. Sé dónde estás. Sé tu dirección. Tengo todos tus datos porque entraste regular y legalmente. Y entonces puedo decir: “Hay más de 500.000 personas ahora que son los beneficiarios de este programa, deportables, y se tienen que ir”.

Silvia: Te queremos preguntar un poco sobre las consecuencias de la cancelación de estos programas, ¿no? ¿Cuál es el impacto emocional para las personas que están afectadas por esto?

María José: Esto es un momento completamente único en la historia para los cubanos dentro y fuera de Cuba.

O sea, estamos hablando de que los Estados Unidos siempre ha sido un país de esperanza para las personas cubanas, por las leyes y los beneficios que estábamos hablando. Es difícil exagerar cuán desastrosa es la situación ahora mismo en Cuba, la situación socioeconómica, la situación política. Entonces, esto impacta de una manera muy directa el sentido de esperanza de las personas dentro y fuera de Cuba.

Además de eso, impacta a las familias. Tenemos familias que van a ser separadas. Hay muchas personas,que entraron juntas como familia y que recibieron diferente trato, y por lo tanto una parte de la familia está ahora mismo en peligro de deportación o encarcelamiento, cuando la otra no lo está. Además de eso, tiene un impacto en las comunidades, ¿no? Tiene un impacto en las economías locales, tiene un impacto en los sistemas de asilo.

Eliezer: Como veíamos en el caso de Lázaro, el asilo es una vía para las personas que pierden el parole. Pero hay muchos retrasos en estos casos, y la administración de Trump también está atacando este proceso. En marzo hubo un récord de peticiones rechazadas.

Silvia: Los cubanos ya llevan muchos años pidiendo asilo. Se estima que hay más de 80.000 casos pendientes de personas cubanas.

María José: Hay un impacto más directo. Yo creo que en eso muchas veces los políticos no han pensado. Digamos que una persona que está con la I-220A o cualquier otra forma que no sea el parole muchas veces, en dependencia del tipo de forma con la cual fueron admitidas, a veces no tienen permiso de trabajo.

Sin permiso de trabajo, no pueden aportar a sus familias y no pueden aportar a las comunidades. Terminan los gobiernos locales asumiendo muchas veces estas responsabilidades. Se ha visto, y yo creo que esto es único, yo nunca había visto, personas en situación de calle, migrantes latinas en Miami. Y esto se está viendo ahora. O sea, estamos viendo a personas cubanas en situación de calle, en una comunidad que históricamente había recibido, de alguna manera, a la migración de Cuba.

Eliezer: María José resaltó que, como se trata de un número tan grande de personas, los perfiles demográficos de los cubanos que llegan a Estados Unidos han cambiado. La migración cubana ha tenido diferentes épocas.

María José: En los años 60, sobre todo clase media alta, personas blancas. Después vimos cambios en los 80 y en los 90. Pero sin lugar a dudas, 500.000 personas vienen de todo tipos digamos de situaciones. En Cuba tenemos muchas más personas LGBT, muchas más personas de la tercera edad que no era común en la migración cubana. O sea, la migración cubana empezaba con mujeres y hombres jóvenes, pero estamos viendo abuelas en migración, estamos viendo niños en migración, estamos viendo comunidades negras en migración.

Y muchas de estas comunidades y de estos grupos no tienen conexiones en los Estados Unidos, como solía pasar hace 30 años, donde había una conexión familiar, una amistad. Entonces, llegas a Estados Unidos, no tienes esa conexión, necesitas trabajo para poder tener una casa, etcétera. No la tienes, y te quedas en la calle. Y eso es un impacto nuevo en la comunidad que yo creo que se está sintiendo mucho. También, generaciones de políticos han construido sus carreras apoyando, digamos, el embargo de Estados Unidos contra Cuba y dando la bienvenida a los cubanos en los Estados Unidos. Siempre ha sido un poco esa la dinámica, sobre todo los políticos en el sur de la Florida, los políticos cubanoamericanos.

La situación actual, yo creo, tiene el potencial de transformar profundamente la política en el sur de la Florida en el futuro cercano. No sé si las personas responsables, los políticos en ambos partidos, están prestando atención a estos cambios. Vamos a tener una población que se va a ver más directamente impactada, y eso yo creo, va a impactar la manera en que los votos se reflejen en dos, cuatro y seis años. Hay mucho miedo en la comunidad, hay mucha tristeza en la comunidad y mucho sentido de desesperación y de falta de guía por parte del gobierno, lo cual no había sido el caso anteriormente.

Silvia: Decías que, claro, en este grupo tan grande hay de todo, ¿no? Hay ancianos, hay niños, también hay disidentes del régimen cubano. ¿Qué mensaje envía esto a ellos?

María José: Yo creo que es un mensaje muy claro de que esa promesa, hay una desconexión entre el discurso y la práctica, ¿no? Por una parte, la política actual del gobierno de los Estados Unidos dice: “Nuestro objetivo es apoyar al pueblo de Cuba. Nuestro objetivo es promover los derechos humanos”. La práctica es lo contrario. La práctica es que, si eres disidente y llegaste aquí y aplicaste con todo tu derecho al refugio, ahora vas a ser enviado a Cuba. Entonces, es un mensaje claro de que el actual gobierno de Estados Unidos en realidad no está interesado en apoyar a aquellas personas que defienden los derechos en Cuba, desde Cuba.

Silvia: O sea, ¿estamos ante un cambio profundo? ¿De que se acabó esa promesa de que Estados Unidos los va a ayudar, los va a cuidar?

María José: Sí, obviamente se acabó esa promesa. O sea, no podemos decir algo diferente. Pero esto no es nuevo. O sea, yo creo que hay que poner la política en perspectiva, ¿no? Osea, empezamos a ver este tipo de medidas en el 2017, con la eliminación de pies secos, pies mojados.

Eliezer: María José se refiere a una política que beneficiaba a los cubanos. Básicamente decía que, una vez que pisaban suelo estadounidense ya sea por mar o por tierra, podían quedarse legalmente en el país y acogerse a la Ley de Ajuste Cubano. Obama terminó con esta política de pies secos, pies mojados como un paso para normalizar las relaciones con Cuba.

María José: Y, obviamente, en ese momento habían relaciones diplomáticas y otro tipo de objetivos de política exterior de Estados Unidos hacia Cuba, que estaban pensando un poco en el crecimiento de la sociedad civil, en el empoderamiento del sector privado en Cuba.

Silvia: Pero el fin de la política de “pies secos, pies mojados” limitó el número de cubanos que podían ajustar su estatus migratorio bajo la Ley de Ajuste, porque al llegar a Estados Unidos ya no recibían automáticamente, sólo por su nacionalidad, el beneficio de quedarse legalmente de manera temporal. Por eso, los que llegaron desde 2017 tienen diferentes estatus migratorios, como nos explicaba antes Laura. El fin de pies secos pies mojados no redujo el número de migrantes cubanos. Siguieron llegando a Estados Unidos, y en cifras récord. Recordemos, más de medio millón están en un limbo legal, sin poder acceder a la ley de ajuste y regular su situación.A esto hay que sumarle la primera administración de Trump, que acabó con el breve deshielo que logró Obama entre los dos países. Trump terminó muchos de los acuerdos y, entre otras medidas, canceló gran parte de los servicios consulares en La Habana.

Eliezer: Con el parole, durante el gobierno de Biden, María José dice que hubo una especie de reorientación de las políticas hacia soluciones humanitarias.

María José: El caso del parole, yo creo que fue un mensaje: “Estamos escuchando, entendemos la necesidad. Estas son las opciones que tienen para llegar a los Estados Unidos de manera regular”. Al mismo tiempo, la administración de Biden implementó otras medidas que limitaban el acceso al asilo, no sólo para las personas cubanas. O sea, esto fue, es un tema que ha, yo creo, dibujado la política migratoria de Estados Unidos en los últimos diez años. Un poco: te ofrezco soluciones, y por otro lado, reduzco las soluciones legales que tienes.

Ahora, en el caso de los cubanos, sí es evidente que hay un abandono de esta tradición de apoyo y de esta tradición de bienvenida en los Estados Unidos, que está pasando también, digamos, con la población venezolana. O sea, estamos hablando de un gobierno de Estados Unidos que dice que en Venezuela hay una dictadura, y que en Cuba hay una dictadura, y al mismo tiempo estamos planificando deportaciones masivas a Venezuela y a Cuba. O sea, es una política totalmente hipócrita.

Silvia: ¿Cuál para ti sería una política migratoria justa y realista para esta comunidad?

María José: Yo diría que debemos mirar lo que ha funcionado de lo que era antes. La migración va a continuar. Los cubanos y otras poblaciones siguen viniendo a Estados Unidos. O sea, eso queda claro. Entonces, en vez de eliminar lo que funciona dentro de un marco legal y ordenado, la idea en realidad sería: ¿cómo se puede expandir a otras poblaciones?

O sea, el caso cubano siempre se ha usado como este ejemplo de privilegios que no deberían existir para los cubanos porque no existen para otras poblaciones, cuando en realidad es un modelo que se ha estudiado, que funciona. O sea, las personas se ajustan, se regularizan, se insertan en la sociedad sin crear ningún tipo de crisis digamos en las economías locales o en los gobiernos locales. Entonces, ¿por qué no pensamos en una Ley de Ajuste para otras poblaciones? ¿Por qué no pensamos en modelos de regularización para otras poblaciones?

Laura: Este episodio fue reportado por mí. Lo producimos con Silvia Viñas. Lo editaron Eliezer Budasoff y Daniel Alarcón. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido y la música son de Elías González.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Suazo, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un pódcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja, y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú para cubrirla. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Soy Laura Rojas Aponte. Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

Eliezer Budasoff: This episode was made possible thanks to the support of CEDA, an organization that brings together governments, civil society, and communities across the Americas to promote policies that improve well-being and respect the dignity and rights of people throughout the hemisphere.

Silvia Viñas: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: And I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

On his first day back at the White House, Donald Trump signed an executive order ending humanitarian parole.

Silvia: It’s a legal provision that different administrations have used for decades, and most recently was implemented by Joe Biden. It granted temporary permission to remain in the U.S. to people who didn’t meet the requirements for a visa but could enter the country for humanitarian reasons.

Eliezer: More than 500,000 Haitians, Nicaraguans, Venezuelans, and Cubans entered the United States with this permit.

Silvia: In January, a memorandum from the Department of Homeland Security also surfaced, stating it authorized expedited deportations of people under parole. And although a judge blocked Trump’s order in April, by the end of May…

Archival audio, anchor: The Supreme Court of the United States has decided to end the humanitarian parole program.

Archival audio, reporter: And what Justice Jackson wrote is blunt. She said the court did not consider the devastating consequences this decision could have on the lives of thousands of migrants with pending cases.

Archival audio, presenter: The Department of Homeland Security will notify hundreds of thousands of immigrants that their permit to live and work in the United States has been revoked, and that they must leave the country.

Eliezer: Today, what happens when the promise of a legal path to migrate dissolves, what is the situation of people who fled countries in crisis, and what does this shift tell us about the U.S. government’s definition of who deserves protection and who doesn’t.

It’s June 20, 2025.

Silvia: Laura, you’ve been reporting for El hilo on Cuban migrants and their particular, though not unique, situation. A few weeks ago, the Supreme Court gave the green light to the Trump administration to end humanitarian parole, and we know there were thousands of Cubans who arrived in the U.S. under this parole. So, to start, can you tell us in general terms what the situation is now for these migrants?

Laura: Well, what I found is that we’re talking about an executive order that leaves more than 100,000 Cubans in a state of uncertainty.

Eliezer: That’s Laura Rojas Aponte. She’s Colombian, but now lives in New York, and she’s a producer for Radio Ambulante Studios.

Silvia: The Cubans she’s referring to arrived in the U.S. fleeing a deep crisis on the island.

Laura: They migrate to the United States under a measure called humanitarian parole, meant to assist people in urgent and extreme situations, and they arrive with this document. And with the executive order and its cancellation, they’re being told, “you no longer have that document.” So, these Cubans are now undocumented, their legal status changes, and they are now deportable. Perfecto, aquí va la segunda sección traducida, continuando con el mismo estilo y formato:

Silvia: You spoke with people, with Cubans who are currently stuck in this kind of limbo. Can you tell us who you met?

Laura: Of course, because I’m trying to understand what’s happening to these thousands of Cubans in the U.S. And I came across a colleague, Lázaro Yuri.

Lázaro Yuri: My name is Lázaro Yuri Valle Roca. I’m an independent journalist. I’ve also been a human rights activist.

Laura: And I realize that his case helps me understand many of these policies that feel so abstract. I find out that Lázaro came to the U.S. a little less than a year and a day ago, which is an important number in this story. I find out he was persecuted. He was urgently trying to leave Cuba. On his own, he published stories about —quote— “oppression” in an outlet called Delibera, and he migrated to the U.S. with his wife.

Eralidis: I’m Eralidis Frómeta, independent journalist.

Laura: Who has been an activist in Cuba since the 1990s.

Eralidis: Wherever there was activity from the Cuban opposition, we were there. And besides documenting things, we also held up little signs, we shouted. And that’s what our political activism has cost our family.

Laura: I first read about their case in the press. I should say his name and face are familiar to many in the community. And so I ended up traveling from New York to Pennsylvania.

Eralidis: We’ve been living here in Lancaster for 11 months.

Laura: A small town, radically different from Havana.

Eralidis: This place is bigger than what we had in Cuba. But this space…

Lázaro Yuri: This space here is bigger. You’re a bit smaller. I mean, maybe from here to there.

Laura: A space that’s basically a rectangle where you find the living room, dining area, and kitchen, and a hallway that leads to a bathroom and a bedroom. And Lázaro and Eralidis say that this is much bigger than what they had in Cuba, where they basically lived in one room with an adjoining kitchen and a little social area. They also remember being constantly watched by the secret police. When I ask them how they knew it was the secret police, they laugh at me. Of course they knew.

Eliezer: Why were both of them so desperate to leave Cuba?

Laura: They’ve been victims of repression since the way they got married. I get to their house and quickly ask, “How long have you been together?”

Lázaro Yuri: We got married while I was in prison.

Laura: But Eralidis corrects him, “We’ve been together 15 years.”

Eralidis: We’ve been married for 15 years, but we legalized it while he was in prison.

Laura: Also, about 11 or 13 years ago, Eralidis became pregnant by Lázaro.

Eralidis: By now we would have had a child who’s 11 or 12 years old. But during a raid, the political police beat me so badly that I lost the baby.

Laura: And she says, “I haven’t been able to give my husband children.” But Lázaro replies, “Well, your kids from your previous marriage are like my own.”

Lázaro Yuri: And the grandkids are lovely, and they love me, and they call me grandpa, and I love them too.

Laura: That’s one starting point. But on the other hand, Lázaro came here directly, basically straight from prison. There was a protest. You can see this on YouTube.

Archival audio, flyer protest: In 2021, marking another anniversary of the birth of our Bronze Titan, a group of activists…

Laura: Lázaro climbed to the top floor of a colonial-era building in Havana, one of those crumbling buildings, and started throwing papers against the regime.

Archival audio, flyer protest: They had quotes from José Martí.

Laura: And that didn’t sit well with the secret police.

Archival audio, flyer protest: People were picking up the flyers, but the police, with dogs, forced passersby to throw them away.

Laura: Later on, Lázaro went to another protest, where the secret police captured and threatened him.

Lázaro Yuri: They told me I had to give up my ideals, to stop doing journalism, to leave my organization and all that. I told them no.

Laura: They said, “You need to stop your journalism or you’ll suffer the consequences.” He said no, and the consequences were that he was arrested and sent to prison. He was sentenced to five years for propaganda. But when you look at his case, it’s not clear if it was five years, or six. They sent him to a maximum security prison where, according to him, there were murderers, people convicted of serious crimes like rape. So his legal process wasn’t very transparent. What’s clear is that he ended up in prison, and he describes the constant surveillance typical for an inmate.

Lázaro Yuri: As soon as you enter prison, you can’t sleep, you can’t accept anything from anyone. You have to watch out, because people are watching you.

Laura: It’s like, you can’t sleep, you’re surrounded by strangers, and you suspect they’re not safe to be around. Going to the bathroom is hard, you can’t communicate.

Lázaro Yuri: I couldn’t even talk on the phone, because everything was being recorded and listened to. I had to hide just to write.

Laura: He’s a journalist at heart, driven to tell what’s happening. So he smuggled out notes and writings to his wife. Every now and then she’d visit, as would his kids, his grandkids. Sometimes he ate, but he started to get sick, developed boils on the back of his neck, stomach issues, skin problems. In one prison, he experienced something horrifying. They strapped him to a stretcher and slid him horizontally.

Lázaro Yuri: Have you seen a morgue? Imagine them putting you, alive, on a tray like that. You can’t move. They push you inside like you’re a corpse. And then a drop of water keeps falling on your forehead. Constant. Constant. Constant.

Laura: And when they pull you out, it’s just to blow freezing air in your face. Then they shove you back in.

Lázaro Yuri: Psychological and physical torture, degrading, meant to break you morally and spiritually.

Laura: In that situation, he decided to stop eating and drinking.

Lázaro Yuri: So imagine all that, and I start convulsing inside that thing, because I went five days without drinking water.

Laura: Their daughter convinced them, “You have to leave Cuba. This is life or death.”

Lázaro Yuri: It’s true. And I didn’t want to go. But she, crying, told me, “Dad, you have to leave, I don’t want you to die.”

Eliezer: After the break, Lázaro and Eralidis manage to leave Cuba. We’ll be right back.

Silvia: Have you ever listened to an episode of El hilo and felt like you wanted to talk about it with someone? We invite you to join a Listening Club to chat about today’s episode with our team next Wednesday, June 25.

Joining us will be the producer of this episode, Laura Rojas Aponte, María José Espinosa, executive director of CEDA, and Daniel Alarcón, editorial director of El hilo and host of Radio Ambulante. You can find the registration link in the description of this episode. It’s also on our website: elhilo.audio.

Silvia: We’re back on El hilo. Eralidis learned about humanitarian parole through one of her brothers, who was already in the United States. He was actually her sponsor, which is a requirement for getting it.

Eliezer: Diplomats and NGOs also helped them. Eralidis says they applied for parole in February 2023, and it was approved fairly quickly. They let Lázaro leave prison to complete the paperwork, always under guard. The part that took the longest was the permit to leave Cuba.

Laura: Out of desperation, Eralidis went to the U.S. embassy, and the officials told her, “Alright, we’re going to help you get the exit permit.” She doesn’t know what happened, but a week later, she had it. So what she’s telling me is that U.S. officials stepped in. But basically, it was a year of waiting.

Eralidis: On June 4, they took him out of prison. They came to my house, under guard, maybe around two in the afternoon. The political police officer arrives and tells me, “Eralidis, pack Lázaro’s travel clothes.”

Laura: From Lázaro’s perspective, he was sick. He was in prison. One day, they took him to a clinic and handcuffed him to a stretcher.

Eralidis: Handcuffed like a criminal, like a criminal. Hands, feet, waist.

Laura: He says they put in a catheter. He repeated this several times. And they let him talk to his wife. That’s when he finds out he’s going to the United States.

Lázaro Yuri: The next morning they woke me up and said, “Come on, you’re leaving, rampampam.”

Laura: When I tell you what he went through, it sounds like good news, but also, as someone who migrated to this country, it feels strange. Because when you migrate, you ask yourself, what do I pack? Right? What photos of my family do I bring? My notebook? Who knows. All those questions you ask yourself when you know your life is about to change, he didn’t have that. His wife packed for both of them. One night at the clinic, and the next day, the airport.

Lázaro Yuri: They took me to the airport, dropped me off, and I walked over to where Lily was, and there were other officers and military personnel there, in civilian clothes.

Laura: They were escorted to the airport, to the plane. They describe how a secret police agent boarded with them, and it wasn’t until they were in the air that he was allowed to get up from his seat.

Silvia: And how are they doing? How is life in the U.S.?

Laura: At first they lived with her brother and his family, but later decided they needed to be independent. So they moved to the apartment where I met them. Part of the —quote— “humanity of humanitarian parole” is that it gives you a work permit. So you arrive somewhere and can begin to support yourself. And that’s also the tragedy of canceling humanitarian parole, because it takes away people’s ability to earn a living and survive. They found work in a soup factory for a few months. That ended. Eralidis, through a Facebook group for Cubans in her city, found a job at a hotel. Lázaro, no, he’s unemployed and has been recovering.

Lázaro Yuri: I arrived weighing 110 pounds. Can you imagine? 110 pounds. I was skin and bones, as we say.

Eralidis: If he hadn’t left Cuba, he probably wouldn’t even be alive right now, he wouldn’t be sitting here telling his story, because he was more dead than alive. He arrived in the U.S. totally worn out, very weak.

Laura: Lázaro is still a thin man. He’s been going to medical appointments regularly. So I understand that work is crucial to survival, but I’m also looking at someone who’s going through major health processes.

Silvia: And how did they find out about the end of humanitarian parole?

Laura: Eralidis got a notification on her phone, opened it, and, to my surprise, found it funny.

Eralidis: I immediately said, “Valle, look at this. Oh, we’re back in Cuba.” And his immediate reaction was, “If they deport us, we’ll jump off the plane in Cuba shouting, ‘Down with the dictatorship!’”

Lázaro Yuri: “Down with the dictatorship!” And we’ll go straight for them. And let them, let them kill me already, and that’s it. I’ll be done with all this.

Eralidis: I said, “They’re going to send us back to Cuba. Can you imagine?”

Laura: The notification said, “Parole Termination.”

Lázaro Yuri: That’s what it says here, look, “Parole Termination.”

Laura: They got the notice and realized their documentation allowing them to stay legally in this country would soon expire. And that, of course, is a blow, but it’s a double blow, because they’re also trying to bring people they love here through the same parole program.

Eralidis: At that moment, my brother was getting ready to file parole paperwork for my daughter and grandkids, and the disappointment was so big that for a moment I even thought about going back to Cuba to be with her. But she told me, “Mom, no, you can’t come back, they’ll kill you. You just can’t.”

Laura: And this is a girl who grew up under repression. A girl whose phone was hacked by the secret police, who sent her sexual images when she was 12 to torment her parents. A girl who became a woman, whose son went to visit his grandfather in prison, knowing he was growing up on an island full of injustice.

So they want to be reunited, just the basic human need to be close to your people. But that’s also another generation, a generation that needs to escape the crisis, and the cancellation of humanitarian parole has blocked that path.

Eralidis: Unfortunately, we can’t have the whole family here. We just couldn’t.

Laura: And it gets even worse, because in the first week of June, Donald Trump announced a travel ban to 19 different countries, including Cuba. So now they won’t even be able to apply for a tourist visa. Humanitarian parole was one of several ways Eralidis and Lázaro could reunite with their family, and that path is now gone. But all the others are falling away too.

So the question for them is, how long, right? When will I be able to hug my grandson again?

Eralidis: The way we left Cuba, right? Even though we came through parole, I have no guarantee that I’ll be allowed to return to Cuba to see my two children, my grandchildren. My mother, who’s still there.

Laura: Like so many migrants, they’re left asking, what do we do now? So they have to figure it out. They’ve already talked to their lawyer and are applying for political asylum.

When the Supreme Court officially approved the end of humanitarian parole, Lázaro sent me a voice message.

Lázaro Yuri: Well, Laurita, imagine. You know this is a huge uncertainty we’re living with, and we’re just waiting, at least in our case.

Laura: And then, after the news about the travel ban, I asked him how he felt, and he said, “We’re still waiting.” And this morning, before talking to you, I wrote to him again to ask how he was doing, and he told me, “We’re still waiting.”

So I feel like we’re looking at Cubans who are constantly waiting, waiting for their humanitarian parole, waiting for an exit permit, waiting to see what the Trump administration will do after taking away legal options, waiting for the lawsuit, waiting, waiting, waiting. And in the meantime, it’s like you can’t put down roots in this new country you’ve arrived in.

So I said goodbye to them with this feeling of, what an impossible situation, what a hard decision. You can’t go back to the island, that’s clear. And the paths to settle here don’t feel solid either.

Silvia: But this isn’t the only legal pathway that’s closing for Cubans, right?

Laura: And that broader context is what’s consumed weeks of reporting for me. Because if you look at it from the perspective of a Cuban who wants to migrate to the U.S., there are several options. As many as there are pathways in the U.S. immigration system, which is complex and full of turns. One way is humanitarian parole. You can also apply for a regular visa, say a tourist visa. You’d have to apply from another country. But also, and I think this is what we see most often in the news, you can cross borders. They call it “brincar fronteras” jumping borders. You go from one country to another, and so on, until you get to Mexico to cross into the U.S. There, you might encounter a border agent who gives you two forms, the infamous I-220A and I-220B.

And this only makes things more complicated, because these two forms are —quote— major deportation documents. One you can receive while your deportation case is ongoing, and the other after you already have a removal order. Around half a million Cubans have the I-220A. Not even activists, lawyers, or Cubans themselves understand why some people get one form or the other. Nobody knows. What we do know is that within the same Cuban family, one person might have humanitarian parole, another might have an I-220A, someone else might get an I-220B, another could have a visa for family reunification or tourism or be a student.

Carla Gloria Colomé Santiago: Maybe for the first time, you’re seeing people in the same family where some are U.S. citizens and others are on the verge of being deported.

Laura: To understand this better, I spoke with Carla Gloria Colomé Santiago, a Cuban journalist also based in New York. Carla covers the stories of Cubans and other Hispanic communities inside and outside the island.

Carla: And that’s causing huge family conflicts, major tensions within the community. A community that, as sociologists and historians have said, is not prepared to deal with this.

Laura: People who have these forms are also living in a state of limbo, just like those whose humanitarian parole was cut short. So what I see is that we’re talking about roughly 600,000 people from Cuba looking to build a future in the U.S., each entering through different legal paths. And the Trump administration is shutting those paths down, leaving them all, again, suspended in midair, at the mercy of U.S. policy.

Carla: In a legal limbo where, basically, no one knows what’s going to happen. They fall into different immigration categories, but those categories prevent them from accessing the privilege of the Cuban Adjustment Act. In 1966, a law was passed, the so-called Cuban Adjustment Act that, for decades, allowed generations of Cubans to come to the U.S. and regularize their immigration status.

Laura: In a nutshell, it’s a law that eventually allows you to obtain U.S. citizenship. It was created a few years after the Cuban Revolution, specifically to offer a special, more direct path for people fleeing the communist regime.

Carla: Basically, it guaranteed you protection. If you have a visa, a tourist visa, a student visa, etc., and you arrive in the country legally, within a year and a day you can apply for the Cuban Adjustment Act and apply for residency. You entered the country, you could get assistance, food stamps, medical insurance, and so on, and you lived for a year with that support, with a work permit, somewhat protected. And then, after a year and a day in the U.S., you could apply under the Cuban Adjustment Act. That’s why most of the Cuban community is documented. That’s what people refer to as the “Cuban privilege” compared to other communities that don’t have that.

Now, for the first time, what’s happening is that this so-called privilege may be at risk. Why? Because never in the history of Cuban migration to the United States have so many people been in complete illegality, in legal limbo, living with so much uncertainty. There are so many people living in fear. In Miami, a city where accidents happen every day, there are many people afraid of being in a car crash. Afraid sometimes… like, “Okay, I’m going to work because I have to, but I’ll come right back.” Not everyone, of course, it’s still a community with a lot of documented people, but there’s fear. And we’re increasingly seeing cases where something we thought would never happen to us is now a reality. I mean, who would have imagined a Cuban mother being deported to the island and leaving behind her almost two-year-old daughter with the father in the U.S.?

Laura: Carla told me about Heidy Sánchez. She crossed borders, arrived here, and received an I-220B form.

Carla: At one point, she was trying to regularize her status because her husband is a U.S. citizen, and eventually that was going to happen. But now? Well, nothing: that status is basically an expedited deportation order, and she has to leave the country.

Laura: At her court date, she’s deported. She ends up back in Cuba and tells the press, “Look, I have my baby’s food in my breasts, and my baby is in the U.S. with my husband.” This case, of course, stirred all kinds of visceral reactions in the community and became somewhat iconic of how cruel these policies can be. And how far are we willing to go to meet deportation quotas? Are we really leaving a baby without food, deporting someone who was simply attending their hearing, just like the law says? She was approved for a family reunification order, just the approval. She still had to submit documents and go through an embassy interview. There were steps left. So, what her lawyer says is that maybe in about a year, she could return and reunite with her family.

Carla, while reporting these stories, is learning not just about the individual cases, but also about how the Cuban community is reacting. And it’s something that has them shaken, because it’s a community that, for the most part, has migrated legally. It’s a community that knows hardship, but not this level of difficulty. And they’re scared.

Carla: Because for the first time, Cubans are experiencing this. Before, the path was easy. The path was: “My family or someone else will host me for a year and a day. Meanwhile, I’ll work, and then I’ll get my residency. Then I can go back to Cuba to visit my family. In five years I’ll be a citizen. Everything’s fine, everything’s perfect.” And for the first time, no. That’s not what’s happening. For the first time, we’re starting to look like migrants from the rest of the world.

Laura: They’re terrified to read the stories that journalists like Carla are publishing, because they don’t think this is just or dignified. And for those Cubans who, by virtue of having legal status, are able to vote, this is forcing them to confront who they supported: 58 percent voted for Trump.

Eliezer: We’ll take one last break, and when we come back, we’ll look at how all of this fits into Trump’s immigration policy, and what the consequences are of ending legal migration pathways. We’ll be right back.

We’re back on El hilo.

Silvia: We’d like to put this into perspective, right? Within the immigration policy of Donald Trump’s administration, what arguments is the government using to cancel humanitarian parole and other legal pathways?

María José: The main argument is that this has been an abuse of the U.S. immigration system and laws, when in fact it was a response, in the specific case of humanitarian parole to a rise in arrivals from Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Haiti to the U.S. border for various reasons.

Eliezer: María José Espinosa is the executive director of the Center for Collaboration and Advocacy in the Americas, CEDA.

María José: A system that, by the way, has worked. Something I think is important to highlight about humanitarian parole is that you need to have a sponsor in the U.S., which involves citizens in receiving these people, in making sure they integrate into communities, that they have jobs, that they have documents, and that they contribute.

So, it mobilized U.S. citizens in a very human way, citizens who decided to welcome people from these four countries, and from Ukraine. Humanitarian parole actually began with people from Ukraine suffering because of the war with Russia.

So, in reality, it’s a very organized system. You know who’s coming, when they’re coming, with very specific permissions. I think the attack is also about the vilification of migration, the rise in xenophobia, creating fear of the other. I think it’s tied to a broader xenophobic and racist political agenda.

Silvia: Could this also be a way to fulfill his promise of mass deportations? Because if you cancel the legal status of those who had parole, that means, well, now they’re deportable. And we know he hasn’t been able to deport as many people as he wanted. So we’re wondering if this is also a tactic.

María José: I think that’s a good point. There is, in fact, a promise of mass deportations. Now, the practical way deportation is implemented is much more complex.

So what we’ve seen is that, since these people entered through a U.S. government program, they’re registered in the system. And as you said, they’re deportable. That means I can find you. I know where you are. I have your address. I have all your information because you entered legally. So now, I can say: “There are over 500,000 people, beneficiaries of this program, who are deportable, and they must go.”

Silvia: We also want to ask about the consequences of canceling these programs. What is the emotional toll on the people affected by all this?

María José: This is a completely unique moment in history for Cubans, both inside and outside the island.

The U.S. has always been a country of hope for Cuban people, because of the laws and benefits we’ve been talking about. It’s hard to overstate how disastrous the current situation is in Cuba socially, economically, and politically. So this change hits hope directly, for those inside and outside of Cuba.

It also affects families. We have families that will be separated. Many entered together as families and received different treatment, and now part of the family faces deportation or detention, while the other part does not.

It also affects communities, right? It affects local economies, it affects asylum systems.

Eliezer: As we saw in Lázaro’s case, asylum is a path for those who lose parole. But there are huge delays, and the Trump administration is also targeting that process. In March, there was a record number of asylum rejections.

Silvia: Cubans have been requesting asylum for many years. There are an estimated 80,000 pending Cuban cases.

María José: There’s another direct impact, and I think politicians don’t consider it often. Let’s say a person is here with an I-220A or another status besides parole. Often, depending on the specific status, they don’t have a work permit.

Without a work permit, they can’t support their families, can’t contribute to their communities. And so local governments end up taking on those responsibilities.

We’ve seen something I think is unprecedented, I’ve never seen it before, which is homeless Latino migrants in Miami. We’re now seeing Cubans living on the street, in a community that historically welcomed Cuban migration.

Eliezer: María José also emphasized that, because this group is so large, the demographics of Cuban migration to the U.S. have shifted. Cuban migration has gone through different phases.

María José: In the 1960s, it was mostly upper-middle-class white people. Later we saw changes in the ’80s and ’90s. But now, without a doubt, 500,000 people are coming from all kinds of situations.

We’re seeing more LGBTQ people, more elderly migrants, which wasn’t common in Cuban migration. It used to be young men and women. Now we’re seeing grandmothers, children, Black communities migrating.

And many of these people don’t have connections in the U.S., unlike 30 years ago when families or friends could host you. So you arrive, you need work, housing, support. And if you don’t have that, you end up on the street. That’s a new reality for the community that I think is being deeply felt.

Also, generations of politicians have built careers supporting the U.S. embargo on Cuba and welcoming Cubans. That’s been the dynamic, especially with Cuban-American politicians in South Florida.

This moment, I think, has the potential to profoundly shift Florida politics in the near future. I’m not sure politicians from either party are paying attention to these changes.

We’re going to have a population that will feel these impacts directly, and that’s going to affect how they vote in two, four, six years. There’s a lot of fear in the community, a lot of sadness, and a sense that the government has abandoned them, which hasn’t always been the case.

Silvia: You mentioned that this group includes everyone, seniors, children, dissidents. What message does this send to them?

María José: I think it’s a very clear message, that the promise has been broken, that there’s a disconnect between rhetoric and reality.

On one hand, the U.S. government says, “We support the Cuban people. We promote human rights.” But in practice, it’s the opposite. In practice, if you’re a dissident and you arrived and applied for asylum, you’re now being sent back to Cuba.

It’s a clear message that the U.S. government is not truly interested in supporting those who defend rights in Cuba.

Silvia: So, are we witnessing a fundamental shift? The end of that promise that the U.S. will help and protect them?

María José: Yes, obviously that promise is over. We can’t say otherwise.

But this isn’t new. We have to put policy in perspective. We started seeing these kinds of measures in 2017, with the elimination of the “pies secos, pies mojados” (wet foot, dry foot) policy.

Eliezer: María José is referring to a policy that benefited Cubans. It basically stated that, once they stepped onto U.S. soil, by land or sea, they could stay legally and qualify under the Cuban Adjustment Act.

Obama ended the “pies secos, pies mojados” (wet foot, dry foot) policy as part of an effort to normalize relations with Cuba.

María José: At the time, there were diplomatic relations and other foreign policy goals aimed at strengthening Cuban civil society and empowering the private sector.

Silvia: But ending the “pies secos, pies mojados” (wet foot, dry foot) policy limited how many Cubans could adjust their status under the Adjustment Act, because once they arrived in the U.S., they no longer automatically, just by nationality, got the temporary legal benefit. So those who came after 2017 have different immigration statuses, as Laura explained earlier. Ending that policy didn’t reduce the number of Cuban migrants. They kept coming to the U.S., in record numbers. Remember, more than half a million are now in legal limbo, unable to access the Adjustment Act and regularize their status. To that, we add Trump’s first administration, which ended the brief thaw that Obama had achieved between the two countries. Trump scrapped many agreements and, among other measures, canceled most consular services in Havana.

Eliezer: With parole under Biden, María José says there was a kind of shift toward humanitarian solutions.

María José: The parole program, I think, was a message: “We hear you. We understand the need. These are the options you have to come to the U.S. legally.”

At the same time, the Biden administration also implemented other measures that limited access to asylum, not just for Cubans. This has defined U.S. immigration policy for the past ten years. On one hand, offering solutions, and on the other, reducing the legal options. Now, in the case of Cubans, it’s very clear that the tradition of support and welcome in the U.S. is being abandoned. This is also happening with Venezuelans.

We’re talking about a U.S. government that says there’s a dictatorship in Venezuela and a dictatorship in Cuba, and yet it’s planning mass deportations to both countries. That’s a completely hypocritical policy.

Silvia: What would a fair and realistic immigration policy look like for this community?

María José: I would say we should look at what worked in the past. Migration will continue. Cubans and other populations will keep coming to the U.S. That’s clear. So instead of eliminating what works within a legal and orderly framework, the real idea should be, how do we expand it to other groups?

The Cuban case is often used as an example of privileges that others don’t have. But in reality, it’s a model that has been studied and proven to work. People adjust, regularize, integrate into society without creating a crisis for local governments or economies. So why not think about an Adjustment Act for other groups? Why not think about regularization models for others?

Laura: This episode was reported by me. I produced it with Silvia Viñas. It was edited by Eliezer Budasoff and Daniel Alarcón. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design and music by Elías González.

The rest of El hilo’s team includes Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Samantha Suazo, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, please consider joining our membership program. Latin America is a complex region, and our journalism needs listeners like you to keep covering it. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and support us with a donation.

If you want to learn more about today’s episode, subscribe to our newsletter at elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it out every Friday.

You can also follow us on social media. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook, and Threads. Find us @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments and tag us when you share episodes.

I’m Laura Rojas Aponte. Thanks for listening.