Caribe

Donald Trump

Nicolás Maduro

Narcotráfico

Despliegue militar

Estados Unidos

Venezuela

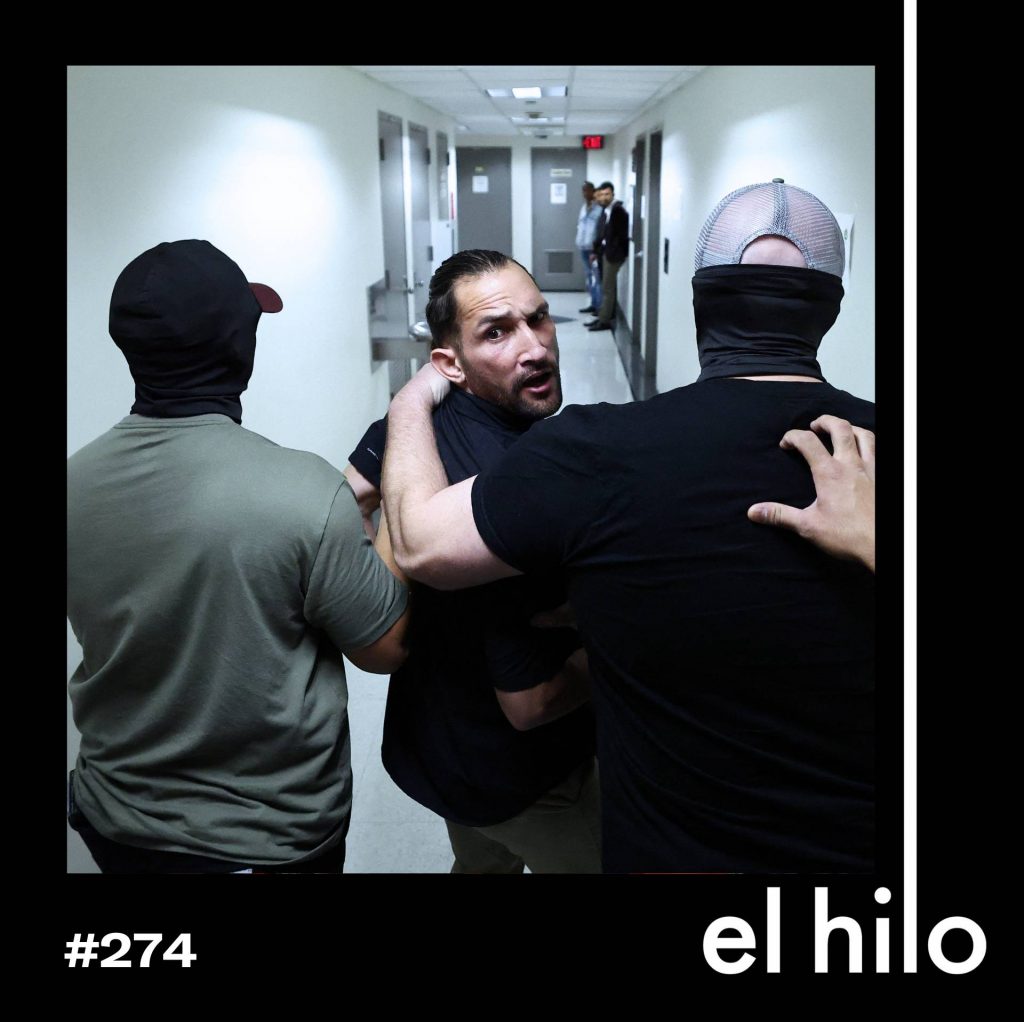

Estados Unidos ha desplegado fuerzas aéreas y navales en el Caribe, y en el último mes ha atacado cinco embarcaciones provenientes de Venezuela, presuntamente cargadas con drogas. El saldo ha sido de al menos 21 personas muertas y una inquietud creciente en la cúpula del chavismo, que empieza a mostrar discrepancias sobre cómo enfrentar esta situación. El gobierno de Donald Trump justifica su ofensiva como parte de su estrategia contra el narco, y a la vez acusa a Nicolás Maduro de encabezar una de las mayores redes de tráfico del mundo. Esta semana, Phil Gunson, analista senior para la región andina del International Crisis Group, nos explica qué hay detrás de esta escalada militar estadounidense, cuál es el escenario real en Venezuela, y por qué las amenazas bélicas de Trump contra Maduro han dejado de ser mera retórica.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Mariana Zúñiga -

Edición

Silvia Viñas, Eliezer Budasoff -

Verificación de datos

Bruno Scelza -

Producción digital

Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elias González -

Música

Elias González -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

Fotografía

The White House

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Eliezer Budasoff: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia Viñas: Y yo soy Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: En agosto, la fiscal general de Estados Unidos duplicó la recompensa por información que lleve al arresto de Nicolás Maduro, a quien acusa de liderar una de las redes de tráfico de cocaína más grande del mundo.

Audio archivo, Pam Bondi: 50 million dollar reward for information leading to the arrest of Nicolás Maduro.

Silvia: La recompensa pasó de 25 a 50 millones de dólares.

Audio archivo, Pam Bondi: Maduro uses foreign terrorist organizations like TDA, Sinaloa and Cartel of the Suns…

Eliezer: También dijo que Maduro colaboraba con organizaciones criminales como El Tren de Aragua, el cartel de Sinaloa y el cartel de Los Soles, para enviar drogas y violencia hacia Estados Unidos.

Silvia: Una semana después, Estados Unidos empezó a mandar a fuerzas aéreas y navales al sur del Caribe.

Eliezer: Y el 2 de septiembre, atacó una lancha.

Audio archivo, noticiero: Un barco que supuestamente transportaba droga procedente de Venezuela y que 11 personas murieron.

Silvia: Al cierre de este episodio, han muerto al menos 21 personas entre ese y otros 4 ataques más. El último fue el viernes 3 de octubre.

Audio archivo, Donald Trump: Bueno, ya no vienen por mar así que ahora tendremos que empezar a buscar por tierra, porque se verán obligados a ir por tierra. Y déjame decirte ahora mismo que eso tampoco les va a salir bien.

Audio archivo, Nicolás Maduro: El imperio se volvió loco y ha renovado como un refrito podrido sus amenazas a la paz y a la tranquilidad de Venezuela. Así que: a avanzar y prepararnos para ganar.

Eliezer: Hoy, qué hay detrás de la escalada militar de Estados Unidos en el Caribe, cuál es el escenario real en Venezuela, y cómo el discurso de guerra contra el narco puede justificar una amenaza bélica real contra Maduro.

Es 10 de octubre de 2025

Silvia: Bueno, la versión de Estados Unidos es que con estos ataques a barcos venezolanos y en general con su despliegue militar en el Caribe, están combatiendo el narcotráfico. Y acusan a Maduro de liderar un cartel, el cartel de los Soles, que Estados Unidos designó como una organización terrorista. Entonces, empecemos por ahí. ¿Quiénes son y qué se sabe sobre la conexión con Maduro, si es que la hay?

Phil Gunson: Mira, el cartel de los Soles como tal no existe. O sea, el cartel de los Soles es una etiqueta que se ha aplicado ya desde hace mucho tiempo para referirse al fenómeno de los militares de alto rango involucrados en el narcotráfico.

Eliezer: Él es Phil Gunson, analista senior para la región andina del International Crisis Group, una organización que se especializa en la prevención de conflictos. Es britanico y lleva 26 años viviendo en Venezuela.

Phil: El gobierno desde hace mucho tiempo ya ha propiciado un ambiente de impunidad. No persiguen, generalmente, a los militares que se involucran en eso. Y con el tiempo eso se ha vuelto una cosa, una práctica muy común. Se ha extendido, evidentemente las conexiones entre militares y no solo el narcotráfico, sino el contrabando de diferentes tipos. Y la razón principal por la que este sistema persiste, esta impunidad persiste, es porque el Gobierno depende cada vez más de los militares para mantenerse en el poder. Es un gobierno ya, evidentemente muy poco popular, y no tiene tampoco mucho dinero ahora para pagar a los militares. Los sueldos, incluso de los altos oficiales, son muy bajos. Entonces este ambiente de impunidad, de permisividad, permite a los militares ganar dinero por fuera, digamos, de los canales regulares, por decirlo así.

Silvia: ¿Entonces, por qué Trump hace esa acusación?

Phil: Si, esa pregunta es muy importante. Yo creo que tiene diferentes razones. La política norteamericana hacia Venezuela tiene diferentes corrientes, con diversos objetivos. En su primer gobierno, Donald Trump pretendía sacar a Maduro del poder abiertamente y aplicó una política de lo que llamaba máxima presión. Que fracasó. Cuando Trump vuelve al poder a principios de este año, Trump empieza en su relación con el gobierno de Venezuela, con una política muy diferente, una política de acercamiento, de negociación a cargo de un señor que se llama Richard Grenell, que fue nombrado enviado especial para Venezuela y algunos otros conflictos en el mundo, pero principalmente Venezuela. Empezó por aquí y logró la liberación de algunos presos norteamericanos.

Audio de archivo, periodista: Venezuela libera a seis estadounidenses tras una reunión diplomática de alto nivel.

Audio de archivo, periodista: Ciudadanos estadounidenses y de otros países acusándolos de participar en presuntos planes contra Maduro impulsados por Washington.

Audio archivo, presos liberados: This is incredible. I’m walking on a cloud. We love you Trump.

Phil: Maduro empezó a aceptar vuelos con deportados venezolanos desde Estados Unidos.

Audio archivo, Maduro: Si por allá no los quieren, nosotros sí los queremos.

Audio de archivo, periodista: El ministro Cabello planteó que estos retornos seguirán ocurriendo mientras exista un diálogo directo.

Diosdado Cabello: Eso es conversado, acá nada es obligado.

Eliezer: Hasta la fecha, Estados Unidos ha repatriado a más de 13 mil venezolanos. Estamos hablando de más de 70 vuelos que han llegado, y siguen llegando, a pesar de las tensiones entre ambos países.

Phil: Y en general se percibía un ambiente de distensión. La idea era que, bueno, no hace falta que saquemos a Maduro del poder si podemos conseguir a través de la negociación todo lo que queremos. Ahora, esa línea no le gustaba mucho al secretario de Estado, Marco Rubio. Rubio, un exsenador de la Florida, hijo de inmigrantes cubanos, siempre ha estado muy dedicado a la idea, no solo de sacar a Maduro del poder, sino de acabar con el régimen en La Habana. También a Daniel Ortega en Nicaragua. Y la política de Trump dio un giro importante cuando necesitaba los votos de los republicanos del sur de la Florida, el grupo que realmente acompaña a Marco Rubio en esto desde el Congreso, necesitaba sus votos para su legislación presupuestaria.

Phil: Entonces Rubio, yo creo que ha podido un poco fusionar, si se puede decir así, las distintas corrientes, porque él obviamente está empujando para sacar a Maduro y su combo del poder. Hay otros que tienen más interés en golpear a los cárteles de la droga y lo han dicho desde mucho antes de que Trump volviera al poder. Otros, digamos, el lobby petrolero, los tenedores de bonos que están muy enfocados en que la economía venezolana mejore y las sanciones se levanten, ¿no? para que las compañías petroleras norteamericanas puedan regresar plenamente a Venezuela. Entonces hay diferentes elementos y Rubio más o menos ha podido unificar todo esto en esta política que involucra ahora a la Marina norteamericana, los militares norteamericanos en un despliegue enorme en el Caribe Sur, que supuestamente tiene que ver con acabar con la droga. Pero no solo eso, sino que como dicen que Maduro es el jefe del cártel de los Soles, entonces se supone que lo que van a hacer es llevarlo a juicio. Pero al margen de todo esto…

Audio archivo, Donald Trump: They continue to send people that we rebuff to our border, they continue to send drugs into our country. Venezuela, they have been very nasty…

Phil: Hay otra cosa muy importante que no se puede dejar de nombrar, que es la política de Trump en cuanto a los inmigrantes en Estados Unidos. Los venezolanos se han convertido, o los han convertido, en blanco predilecto de Trump.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: Por segunda ocasión la Corte Suprema permite, le permite al gobierno de Donald Trump, seguir adelante con la cancelación del estatus de Protección Temporal para los venezolanos.

Audio de archivo, presentador: La administración del presidente Trump había presentado una solicitud de emergencia a principios de este mes pidiéndole a los jueces que le permitieran retirar las protecciones que habían sido extendidas a unos 300 mil venezolanos.

Audio de archivo, presentadora: La Corte no explicó sus razones, lo cual es común en casos de emergencia, pero el mensaje es claro: están dejando la puerta abierta para que la Casa Blanca tenga amplia discreción sobre la continuidad o eliminación del TPS.

Phil: Y esta idea de que los migrantes venezolanos en Estados Unidos son infiltrados, son enviados por Maduro, no solo para llevar drogas, sino también para sembrar la violencia y el caos y causarle problemas al gobierno de Estados Unidos. Eso ha hecho que los venezolanos en particular sean un blanco de esto. Y entonces hemos visto muchas deportaciones, incluso un grupo que fue enviado sin beneficio de juicio, al CECOT en El Salvador. Entonces todas esas cosas están como mezcladas, es muy difícil decir hay un solo objetivo.

Silvia: Claro, pero ¿cuál es el papel que juega Venezuela en la cadena de narcotráfico? O sea, entiendo que no es un país que produzca fentanilo, por ejemplo, ¿no?

Phil: No, el fentanilo, que es de lejos, el problema de drogas más importante que tiene Estados Unidos en este momento si uno lo mide por la cantidad de muertes por sobredosis. El fentanilo se produce en México y se trafica a través, principalmente, a través de la frontera México-Estados Unidos. Pero Venezuela, en particular Venezuela, entra en este cuadro porque Venezuela está al lado del país, Colombia, que produce la mayor cantidad de cocaína del mundo, y por supuesto, como Colombia y Venezuela comparten una frontera de más de 2.000 kilómetros, una parte de esa droga se desvía por acá. La realidad es que la mayor parte de la droga, de la cocaína, que entra a Estados Unidos va directo al norte, va vía el Pacífico, Y muy poca cocaína está entrando a Estados Unidos a través de Venezuela. Y es lógico porque, si primero tiene que entrar por Venezuela, está yendo hacia el este, no hacia el norte. Buena parte de la droga que pasa por aquí termina en Europa, no en Estados Unidos. Entonces en realidad, aunque Venezuela sí es un eslabón importante en la cadena del narcotráfico, está muy lejos de ser el más, la más importante.

Silvia: ¿Y es legal que Estados Unidos meta a su ejército, a su marina, a hundir este tipo de lanchas?

Phil: Bueno, es común, relativamente común, que la Marina norteamericana haga patrullas en el Caribe para detener embarcaciones con drogas. Pero eso es una cosa. Es decir, una cosa es ejercer esa función policial, investigar, y otra cosa es hundir sin siquiera preguntar o entrar en conversación con los que están a bordo y matar a los que están a bordo.

Phil: Eso es una violación de las leyes internacionales, es una violación incluso del código militar de los propios Estados Unidos. Y es un asesinato. De hecho, lo que nos dicen las fuentes legales y militares en Estados Unidos es que ni siquiera con lo que Trump acaba de hacer…

Audio archivo, noticiero: El presidente Donald Trump declaró hace muy poco que los carteles de la droga del Caribe son combatientes ilegales y afirmó que Estados Unidos se encuentra ahora en un conflicto armado no internacional.

Phil: Y con eso pretende justificar estas acciones. Pero no, no llega a… ni remotamente a justificar este tipo de acción, porque de lo que se trata esde civiles, sospechosos de estar traficando drogas, pero que no representan ninguna amenaza mortal a ningún norteamericano y mucho menos a sus militares. Esto realmente es un muy mal precedente, no solo en este teatro en particular, sino para lo que piensa y hace el gobierno de Trump en términos del uso de sus de sus fuerzas militares.

Silvia: Es interesante que uses la palabra “teatro”. Sí, en este teatro también está Maduro, ¿no? Y Maduro ha reaccionado con varias declaraciones.

Audio archivo, Nicolás Maduro: El cambio de régimen, además de ilegal, es inmoral.

Maduro: Hoy estamos más fuertes que ayer. Hoy estamos más preparados para defender la paz.

Maduro: Yo lo he dicho muchas veces: yo a él lo respeto. Diferencias hemos tenido y tenemos.

Silvia: Pero más allá de lo que ha dicho. ¿Cuál es su versión? O sea, ¿qué idea está tratando de instalar sobre los ataques a estas lanchas y lo que dice Estados Unidos, esas acusaciones?

Phil: El gobierno de Maduro, y antes de Maduro el gobierno de Hugo Chávez, que fundó este movimiento chavista que tiene ya 26 años en el poder, ellos siempre se han enfrentado a Estados Unidos, es decir, han considerado a Estados Unidos como el enemigo principal. Entonces, lo que estamos viendo en este momento es algo que ya veían venir y tienen años preparándose militarmente para enfrentar este tipo de cosas. Evidentemente no, no puede, o sea en términos de la guerra convencional. Ese es el contexto general. Ahora, Maduro viendo esto y viendo que la cara que está en el afiche de “Wanted”, ¿no? de buscado, naturalmente está nervioso y quiere evitar este conflicto porque lo más probable es que si se lleva a cabo un enfrentamiento militar, entonces la primera víctima, no sé si mortal, pero por lo menos la víctima en el sentido de que lo llevarían preso, sería el propio Maduro. Entonces Maduro, sabiendo que no tiene cómo enfrentar esto, ha tratado de hacer dos cosas un poco contradictorias. Por un lado tiene que mantener la retórica antiimperialista, pero al mismo tiempo manda mensajes a cada rato a Trump diciendo queremos negociar.

Audio de archivo, Maduro: Y Venezuela siempre ha estado en la disposición de conversar, dialogar.

Phil: Pero al mismo tiempo, aquí en Venezuela no todos los que están en el gobierno sienten lo mismo.

Audio de archivo, Diosdado Cabello: Yo creo que llegó la hora de la guerra revolucionaria contra un enemigo poderoso.

Phil: El ministro del Interior, generalmente considerado como el número dos, Diosdado Cabello, es un señor que sabe muy bien que sí, en cualquier negociación, él podría ser el negociado. Es decir, él no tiene nada que sacar, en otras palabras, de una negociación. Entonces, la retórica de Cabello ha sido muy distinta. Él ha estado hablando y un poco empujando a Maduro hacia una postura un poco más belicosa.

Venezuela no tiene cómo enfrentar esto, pero lo que sí ha hecho, es modificar la doctrina militar venezolana. De tal manera que el escenario que se prevé en este momento es: bueno, se resiste hasta donde se puede convencionalmente y luego se pasa a lo que podríamos llamar una guerra de guerrillas, lo que ellos llaman la revolución armada, la revolución de todo el pueblo.

Silvia: ¿Cuando dices guerra de guerrillas, te refieres a la gente, civiles, tomando las armas?

Audio de archivo, Maduro: El pueblo a sus unidades militares, para recibir adiestramiento teórico, estratégico…

Eliezer: Maduro dijo que más de ocho millones de milicianos están enlistados, pero según Phil, y otros expertos en fuerzas militares, la realidad es muy diferente.

Phil: Primero, son mucho menos. O sea, pueden ser unas decenas de miles, posiblemente. Están muy mal entrenados. Por lo general están peor armados. Y su papel, tristemente, sería de carne de cañón. O quizá escudos humanos. Maduro perdió una elección presidencial en julio del año pasado, por un margen muy amplio. Maduro no es popular y la mayoría de los venezolanos no está dispuesta a salir a la calle a defenderlo. Mucho menos contra un ataque militar de Estados Unidos. Habrá quienes sí lo defienden, pero la idea de que, esta revolución armada de la que habla Diosdado Cabello en particular, signifique que el pueblo entero se dedique a resistir al invasor, eso es fantasioso.

Phil: Pero dicho eso, aquí en Venezuela hay muchísimos grupos armados no estatales que tienen vínculos de distintos tipos con el gobierno. Muchos de ellos muy bien armados. En primerísimo lugar, el Ejército de Liberación Nacional Colombiano, que está formalmente y en la práctica comprometido con la defensa de la Revolución Bolivariana. Bueno, no sabemos exactamente cuántos hay aquí de este lado de la frontera, pero puede ser entre mil y 2.000 combatientes, pero combatientes con bastante experiencia y muy bien armados. También tenemos a los famosos colectivos, los grupos parapoliciales del chavismo, que también están armados y tenemos grupos criminales, muchos de ellos mejor armados, por lo menos que la Policía. Y entonces, cuando uno suma todo eso y piensa en una potencial, una situación, digamos post derrocamiento, digamos si se logra decapitar este gobierno, vendrá un periodo de muchísima incertidumbre.

Phil: ¿Quién va garantizar la seguridad interna de Venezuela? ¿Quién va a enfrentar esta amenaza? ¿Está Estados Unidos dispuesto a entrar con tropas para garantizar la seguridad? Y de ser así, ¿cuántos se necesitan y por cuánto tiempo? Trump siempre ha dicho que no quiere involucrarse en otra guerra interminable. Entonces yo creo que eso es algo que no han pensado muy a fondo. Me sorprendería si hubiera un plan acabado para enfrentar eso, porque la versión que oímos de María Corina Machado es prácticamente que aquí no va a haber resistencia, no va a haber ningún problema de seguridad porque la gente va, toda la gente va a salir a la calle a bailar y a festejar. Y los que no están con el júbilo se irán o estarán presos. Yo creo que es un poco una caricatura de la realidad.

Eliezer: Hacemos una pausa y volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Silvia: Bueno, nos gustaría poner todo esto un poco en el contexto regional también, porque claro, los ataques a los barcos venezolanos han sido como lo más mediático, pero Estados Unidos ha aumentado su presencia militar en otras partes del Caribe. Como decíamos, ¿no? en este segundo gobierno de Trump, su administración declaró a varios grupos narcotraficantes como organizaciones terroristas, y el jueves 2 de octubre Trump le dijo al Congreso que el país estaba formalmente en un conflicto armado con los cárteles. ¿Crees que están de alguna manera llevando la guerra contra las drogas, que lleva tantos años en Latinoamérica, a otro nivel?

Phil: Sí, definitivamente. Pretenden convertirlo de metáfora, en realidad, en guerra de verdad.

Phil: Es obvio, digamos, desde mucho antes de la llegada de Trump nuevamente al poder. Que muchos del equipo de Trump, ellos lo que quieren es… lo que piensan en cuanto al narcotráfico, es que la manera de enfrentarlo es militarmente. Mandando drones, mandando fuerzas especiales a territorio de otros países. Ahora, el primer país en la mira ha sido México. Y su presidente, Claudia Sheinbaum, ha sido enfática en ese sentido, que no lo va a permitir.

Audio de archivo, Claudia Sheinbaun: Estados Unidos no va a venir a México con los militares. Cooperamos, colaboramos, pero no va haber invasión. Eso está descartado.

Phil: Visto eso. Visto que es difícil y por muchas otras razones, porque la relación México-Estados Unidos es una relación muy compleja, es más fácil llevar a cabo lo que pretenden hacer aquí en Venezuela, con la idea de mandar un mensaje a los demás países y seguramente piensan seguir con esto. Pero mucho va a depender de cómo les va en este teatro claro, han logrado un cese temporal del flujo de droga desde Venezuela a través del Caribe Oriental. Es lógico, nadie quiere sacar una lancha en este momento con drogas o incluso sospechosa de tener droga, sabiendo que es un suicidio. Entonces, por ahora ese flujo está detenido. Pero en el narcotráfico, los narcotraficantes son muy adaptables y tienen muchos recursos, mucho dinero, mucha droga, muchas armas y otras rutas.

Phil: ¿Y la región? Bueno, algunos están de acuerdo y lo han dicho públicamente algunos aliados de Estados Unidos: Argentina, Ecuador, por ejemplo, han declarado su apoyo a esta política. Trinidad y Guyana, vecinos muy cercanos, están aún más entusiasmados, ¿no? Incluso ofreciendo territorio, su territorio, para cualquier acción armada en el caso de que haya una agresión por parte de Maduro, cosa que yo creo que él va a tratar de evitar a toda costa. Pero en general la región tiene un dilema porque saben cómo es Trump, no quieren otra pelea con Trump, no quieren tampoco defender a Maduro ni al narcotráfico. Entonces… O sea, obviamente ha habido desacuerdos públicos. Petro en Colombia, por supuesto, en primer lugar.

Audio de archivo, Gustavo Petro: Los gringos están en la olla si piensan que invadiendo Venezuela resuelven su problema.

Phil: Y Lula también utilizó su discurso en Naciones Unidas para criticar este tipo de política.

Audio de archivo, noticias Brasil: Y además hay movimientos a prestarle atención: Brasil ha enviado 10 mil soldados a la frontera con Venezuela.

Phil: Pero no van a hacer nada. Es decir, nadie va a salir a defender a Maduro. Quizá un poco, habrá seguramente comunicados, expresando desacuerdo, pero nada práctico para ayudar a Maduro, mucho menos para defenderlo.

Silvia: Has mencionado a Colombia y me parece que es un actor importante en todo esto, ¿no? por ser vecino de Venezuela, pero también por su relación con Estados Unidos y que el mes pasado el gobierno de Trump le quitó a Colombia la certificación en la lucha contra el narcotráfico. ¿Qué significa que Colombia haya perdido eso y cuál es la justificación de Estados Unidos para hacerlo? Y si se relaciona a esta estrategia, o política de Estados Unidos en la región.

Phil: Bueno, el gobierno de Trump no ha hecho ningún secreto de su desacuerdo con Petro. O sea, no ve a Petro como un aliado en ningún sentido. Ellos están esperando ansiosamente el fin del gobierno de Petro que viene el año que viene y esperan que sea reemplazado por una figura mucho más cercana a su punto de vista. La descertificación, bueno, siempre ha sido, o sea, anualmente se debate eso en Estados Unidos porque, obviamente, es muy difícil declarar que Colombia está haciendo todo lo posible por frenar el narcotráfico viendo el volumen de droga que sale de ahí. Y además el hecho de que ha habido un aumento significativo en la producción de droga. Pero al mismo tiempo Estados Unidos ha sido históricamente el aliado más firme y viceversa, ¿no? Colombia, es el aliado más firme de Estados Unidos en el hemisferio. Ha recibido muchísima ayuda militar y de todo tipo. Si hubiera descertificado a Colombia sin el acompañante waiver, como dice, la exención que permite que estos programas sigan, la situación sería mucho peor para Petro y para Colombia.

Phil: Pero, parece que Estados Unidos todavía entiende que el problema con castigar a Colombia es que corres el riesgo de desestabilizar un gobierno que tiene múltiples problemas en materia de, no solo de crimen organizado, narcotráfico, sino de insurgencia. Sería una estupidez desestabilizar Colombia. Incluso si el gobierno del momento no te gusta, Colombia sigue siendo una democracia.

Phil: Pero por supuesto, el presidente Petro no está ayudando. Petro ha dicho que un ataque a Venezuela es un ataque a Colombia y a todo el continente. Y ha pretendido de alguna manera fusionar las Fuerzas Armadas colombianas con las venezolanas. Pretende que compartan inteligencia y eso. Y esas cosas no sólo no son convenientes desde un punto de vista de una política sensata, racional, en este momento específico con el gobierno de Trump al acecho, sino que realmente no tiene ningún sentido pretender aliarse de esa manera con un gobierno de la naturaleza del que tenemos en Venezuela.

Eliezer: Hacemos una última pausa y volvemos

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta.

Silvia: Bueno y regresando a Venezuela. Tú vives ahí hace casi 30 años. ¿Cómo está el ambiente? ¿Las personas tienen miedo, están preocupadas de que Estados Unidos vaya a invadir el país o algo por el estilo? ¿Cuál es, como, el ambiente por allá?

Phil: Si vinieras acá, en este momento, a Caracas y sin saber nada de esto, a lo mejor ni te das cuenta. La gente tiene que proceder con sus vidas diarias. Tenemos una situación económica extremadamente mala. La mayoría de la gente vive en pobreza. La gente tiene que trabajar y tratar de ganar lo suficiente como para alimentarse, etc. La otra cosa que creo que es importante entender es que aquí la información es escasa. Los medios masivos están o en manos del gobierno o intimidados. Mucha gente no tiene mucha información sobre lo que está pasando, excepto la información que les da el gobierno. Ciertamente hay gente muy nerviosa, sobre todo los que han sido seguidores del gobierno, o han sido funcionarios, o siguen siendo funcionarios. Luego hay un grupo, ciertamente… Es muy difícil saber cuántos son, porque aquí las encuestas ya prácticamente dejaron de salir públicamente. Pero sí hay gente que está entusiasmada, que quieren que vengan los militares norteamericanos, que creen honestamente que con esto se acaba el problema y que todo el mundo va a vivir feliz después. Después yo creo que en el medio hay mucha gente que se burla, que se ríe de la situación, que cree que es un bluff más o que simplemente está esperando a ver qué pasa. Y a uno que bueno, pretende analizarlo, siempre le caen las preguntas, ¿no? O sea, ¿qué va a pasar, no? ¿Esto es en serio? O sea, ¿van a llegar los marines? Y bueno, uno trata de responder de la mejor manera posible.

Silvia: Y ¿cómo respondes? O sea, ¿a ti te preocupa, por ejemplo, escuchar a Trump decir que podrían llevar los ataques al narcotráfico desde el mar hasta dentro del territorio venezolano? O sea, ¿crees que está allanando el camino para una posible invasión o cambio de régimen como querría Marco Rubio?

Phil: Yo empecé como muchos creo, hace como mes y medio cuando esto empezó, mi primera impresión fue ajá, es otro bluff más, lo hemos visto antes, ¿no? Es otra fase de la máxima presión y cuando se vaya la flota, Maduro va a estar en el poder todavía. Con los días, con el aumento de la fuerza, y la retórica cada vez más encendida, cada día parece menos bluff y más real.

Es cada vez más difícil pensar que todo esto es simplemente un bluff muy caro, no sabría si estamos hablando de un 50-50, si ahora es más probable que… Sabemos que siguen evaluando sus opciones. Entonces tampoco creo que esté tomada la decisión todavía, pero ya… O sea, si empezamos a oír explosiones en Caracas, yo creo que obviamente va a ser dramático, pero no tan sorprendente porque ya parece que es lo que pretenden, es lo que declaran que, prácticamente, que van a hacer. No sé si va a ser aquí en la capital, no sé qué pretenden, o si la intención sería hacerlo todo de una vez o escalar paulatinamente para darle la impresión a Maduro que sí vienen por él y convencerlo que tiene que irse del país, no sabemos. Pero alguna acción militar en tierra creo que ahora es más probable que no.

Eliezer: Esta semana, Donald Trump ordenó a Richard Grenell, el enviado especial de la Casa Blanca a Venezuela, suspender todo contacto diplomático con el país, incluidas las conversaciones con Maduro. Además, el Departamento de Justicia de Estados Unidos aprobó el uso de fuerza letal contra una lista secreta de carteles de narcotráfico.

Silvia: El partido Demócrata introdujo una moción en el Senado para bloquear los ataques militares en el Caribe, pero fue rechazada. Y en Colombia, Gustavo Petro dijo que la última lancha bombardeada por Estados Unidos era de su país y llevaba ciudadanos colombianos.

Mariana: Este episodio fue producido por mí, Mariana Zúñiga. Lo editaron Silvia y Eliezer. Bruno Scelza hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido y la música son de Elías González

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Eliezer: Welcome to El Hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: And I’m Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer Budasoff: In August, the U.S. Attorney General doubled the reward for information leading to the arrest of Nicolás Maduro, whom she accused of leading one of the world’s largest cocaine trafficking networks.

Audio archive, Pam Bondi: 50 million dollar reward for information leading to the arrest of Nicolás Maduro.

Silvia Viñas: The reward went from 25 to 50 million dollars.

Audio archive, Pam Bondi: Maduro uses foreign terrorist organizations like TdA, Sinaloa and Cartel of the Suns…

Eliezer: She also said that Maduro was collaborating with criminal organizations like Tren de Aragua, the Sinaloa cartel, and the Cartel of the Suns, to send drugs and violence to the United States.

Silvia: A week later, the United States began sending air and naval forces to the southern Caribbean.

Eliezer: And on September 2nd, they attacked a speedboat.

Audio archive, news: A boat that allegedly was transporting drugs from Venezuela and 11 people died.

Silvia: As of the closing of this episode, at least 21 people have died between that and 4 other attacks. The last one was on Friday, October 3rd.

Audio archive, Donald Trump: Well, they’re not coming by sea anymore so now we’re going to have to start looking on land, because they’ll be forced to go by land. And let me tell you right now that’s not going to work out well for them either.

Audio archive, Nicolás Maduro: The empire has gone crazy and has renewed like a rotten rehash of its threats to the peace and tranquility of Venezuela. So: let’s move forward and prepare ourselves to win.

La traducción de esa frase al inglés es:

Eliezer: Today, what is behind the US military escalation in the Caribbean, what is the real scenario in Venezuela, and how the discourse of the war on drugs can justify a real war threat against Maduro.

It’s October 10th, 2025.

Silvia: Well, the United States’ version is that with these attacks on Venezuelan boats and generally with their military deployment in the Caribbean, they’re combating drug trafficking. And they accuse Maduro of leading a cartel, the Cartel of the Suns, which the United States designated as a terrorist organization. So, let’s start there. Who are they and what is known about the connection with Maduro, if there is one?

Phil Gunson: Look, the Cartel of the Suns as such doesn’t exist. I mean, the Cartel of the Suns is a label that has been applied for a long time to refer to the phenomenon of high-ranking military officers involved in drug trafficking.

Eliezer: This is Phil Gunson, senior analyst for the Andean region at the International Crisis Group, an organization that specializes in conflict prevention. He’s British and has been living in Venezuela for 26 years.

Phil: The government has long fostered an environment of impunity. They generally don’t prosecute the military personnel who get involved in it. And over time that’s become a very common practice. It has spread, evidently the connections between military personnel and not only drug trafficking, but smuggling of different types. And the main reason why this system persists, this impunity persists, is because the Government increasingly depends on the military to stay in power. It’s evidently already a very unpopular government, and they also don’t have much money now to pay the military. The salaries, even of high-ranking officers, are very low. So this environment of impunity, of permissiveness, allows the military to earn money outside of regular channels, so to speak.

Silvia: So, why does Trump make that accusation?

Phil: Yes, that question is very important. I think there are different reasons. American policy toward Venezuela has different currents, with various objectives. In his first government, Donald Trump intended to remove Maduro from power openly and applied a policy of what he called maximum pressure. Which failed. When Trump returns to power at the beginning of this year, Trump starts his relationship with the Venezuelan government with a very different policy, a policy of rapprochement, of negotiation led by a man named Richard Grenell, who was named special envoy to Venezuela and some other conflicts in the world, but mainly Venezuela. He started here and achieved the release of some American prisoners.

Archive audio, host: Venezuela releases six Americans after a high-level diplomatic meeting.

Archive audio, host: American citizens and from other countries accusing them of participating in alleged plots against Maduro driven by Washington.

Archive audio, released prisoners: This is incredible. I’m walking on a cloud. We love you Trump.

Phil: Maduro began accepting flights with deported Venezuelans from the United States.

Archive audio, Maduro: If they don’t want them over there, we do want them.

Archive audio, host: Minister Cabello stated that these returns will continue to occur as long as there is direct dialogue.

Diosdado Cabello: That’s discussed, nothing here is forced.

Eliezer: To date, the United States has repatriated more than 13 thousand Venezuelans. We’re talking about more than 70 flights that have arrived, and continue to arrive, despite the tensions between both countries.

Phil: And in general there was a perceived atmosphere of détente. The idea was that, well, we don’t need to remove Maduro from power if we can get through negotiation everything we want. Now, that line didn’t please the Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, very much. Rubio, a former senator from Florida, son of Cuban immigrants, has always been very dedicated to the idea, not only of removing Maduro from power, but of ending the regime in Havana. Also Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua. And Trump’s policy took an important turn when he needed the votes of Republicans from South Florida, the group that really accompanies Marco Rubio in this from Congress, he needed their votes for his budget legislation.

Phil: So Rubio, I think has been able to somewhat fuse, if you will, the different currents, because he’s obviously pushing to remove Maduro and his gang from power. There are others who have more interest in hitting the drug cartels and they’ve said so long before Trump returned to power. Others, let’s say, the oil lobby, the bondholders who are very focused on the Venezuelan economy improving and sanctions being lifted, right? so that American oil companies can fully return to Venezuela. So there are different elements and Rubio has more or less been able to unify all this in this policy that now involves the American Navy, the American military in a huge deployment in the Southern Caribbean, which supposedly has to do with ending drugs. But not only that, but since they say Maduro is the head of the Cartel of the Suns, then it’s supposed that what they’re going to do is bring him to trial. But aside from all this…

Archive audio, Donald Trump: They continue to send people that we rebuff to our border, they continue to send drugs into our country. Venezuela, they have been very nasty…

Phil: There’s another very important thing that can’t be left unmentioned, which is Trump’s policy regarding immigrants in the United States. Venezuelans have become, or have been made into, Trump’s favorite target.

Archive audio, host: For the second time the Supreme Court allows the government of Donald Trump to move forward with the cancellation of Temporary Protected Status for Venezuelans.

Archive audio, host: The Trump administration had filed an emergency request earlier this month asking judges to allow it to remove the protections that had been extended to some 300 thousand Venezuelans.

Archive audio, host: The Court didn’t explain its reasons, which is common in emergency cases, but the message is clear: they’re leaving the door open for the White House to have broad discretion over the continuation or elimination of TPS.

Phil: And this idea that Venezuelan migrants in the United States are infiltrators, are sent by Maduro, not only to bring drugs, but also to sow violence and chaos and cause problems for the United States government. That has made Venezuelans in particular a target of this. And so we’ve seen many deportations, even a group that was sent without benefit of trial, to CECOT in El Salvador. So all those things are sort of mixed up, it’s very hard to say there’s a single objective.

Silvia: Right, but what role does Venezuela play in the drug trafficking chain? I mean, I understand it’s not a country that produces fentanyl, for example, right?

Phil: No, fentanyl, which is by far the most important drug problem that the United States has right now if you measure it by the number of overdose deaths. Fentanyl is produced in Mexico and is trafficked through, mainly, through the Mexico-United States border. But Venezuela, particularly Venezuela, enters this picture because Venezuela is next to the country, Colombia, which produces the largest amount of cocaine in the world, and of course, since Colombia and Venezuela share a border of more than 2,000 kilometers, some of that drug gets diverted through here. The reality is that most of the drugs, of the cocaine, that enters the United States goes straight north, it goes via the Pacific, and very little cocaine is entering the United States through Venezuela. And it’s logical because, if it first has to enter through Venezuela, it’s going east, not north. A good part of the drugs that pass through here end up in Europe, not in the United States. So in reality, although Venezuela is an important link in the drug trafficking chain, it’s far from being the most important.

Silvia: And is it legal for the United States to send in its army, its navy, to sink this type of speedboat?

Phil: Well, it’s common, relatively common, for the American Navy to patrol in the Caribbean to stop vessels with drugs. But that’s one thing. I mean, one thing is to exercise that police function, investigate, and another thing entirely is to sink without even asking or entering into conversation with those who are on board and kill those who are on board.

Phil: That’s a violation of international laws, it’s a violation even of the United States’ own military code. And that’s murder. In fact, what legal and military sources in the United States tell us is that not even with what Trump just did…

Archive audio, news: President Donald Trump declared just recently that the Caribbean drug cartels are illegal combatants and stated that the United States is now in a non-international armed conflict.

Phil: And with that he intends to justify these actions. But no, it doesn’t even remotely justify this type of action, because what we’re dealing with are civilians, suspects of trafficking drugs, but who don’t represent any mortal threat to any American and much less to their military. This really is a very bad precedent, not only in this particular theater, but for what the Trump government thinks and does in terms of the use of its military forces.

Silvia: It’s interesting that you use the word “theater.” Yes, in this theater Maduro is also present, right? And Maduro has reacted with several statements.

Archive audio, Nicolás Maduro: Regime change, besides being illegal, is immoral.

Maduro: Today we are stronger than yesterday. Today we are more prepared to defend peace.

Maduro: I’ve said it many times: I respect him. We’ve had differences and we have them.

Silvia: But beyond what he’s said. What’s his version? I mean, what idea is he trying to establish about the attacks on these speedboats and what the United States says, those accusations?

Phil: Maduro’s government, and before Maduro Hugo Chávez’s government, which founded this Chavista movement that has been in power for 26 years now, they have always confronted the United States, that is, they’ve considered the United States as the main enemy. So, what we’re seeing right now is something they already saw coming and they’ve spent years preparing militarily to face this type of thing. Evidently not, they can’t win in terms of conventional war. That’s the general context. Now, Maduro seeing this and seeing that the face that’s on the “Wanted” poster, right? of wanted, naturally is nervous and wants to avoid this conflict because most likely if a military confrontation takes place, then the first victim, I don’t know if fatally, but at least the victim in the sense that they would take him prisoner, would be Maduro himself. So Maduro, knowing he has no way to face this, has tried to do two things that are somewhat contradictory. On one hand he has to maintain the anti-imperialist rhetoric, but at the same time he sends messages all the time to Trump saying we want to negotiate.

Archive audio, Maduro: And Venezuela has always been willing to talk, to dialogue.

Phil: But at the same time, here in Venezuela not everyone in the government feels the same way.

Archive audio, Diosdado Cabello: I think the time has come for revolutionary war against a powerful enemy.

Phil: The Interior Minister, generally considered as number two, Diosdado Cabello, is a man who knows very well that yes, in any negotiation, he could be the one negotiated. That is, he has nothing to gain from a negotiation. So Cabello’s rhetoric has been very different. He’s been talking and somewhat pushing Maduro toward a somewhat more belligerent posture.

Venezuela has no way to face this, but what it has done is modify Venezuelan military doctrine. In such a way that the scenario foreseen at this moment is: well, they resist as far as possible conventionally and then move on to what we could call guerrilla warfare, what they call the armed revolution, the revolution of all the people.

Silvia: When you say guerrilla warfare, are you referring to the people, civilians, taking up arms?

Archive audio, Maduro: The people to their military units, to receive theoretical, strategic training…

Eliezer: Maduro said that more than eight million militia members are enlisted, but according to Phil, and other military experts, the reality is very different.

Phil: First, there are much fewer. I mean, there could be a few tens of thousands, possibly. They’re very poorly trained. Generally they’re worse armed. And their role, sadly, would be cannon fodder. Or perhaps human shields. Maduro lost a presidential election in July of last year, by a very wide margin. Maduro is not popular and the majority of Venezuelans aren’t willing to take to the streets to defend him. Much less against a military attack by the United States. There will be those who do defend him, but the idea that this armed revolution that Diosdado Cabello in particular talks about means that the entire population will dedicate itself to resisting the invader, that’s fanciful.

Phil: But having said that, here in Venezuela there are many non-state armed groups that have links of different types with the government. Many of them are very well armed. First and foremost, the Colombian National Liberation Army, which is formally and in practice committed to defending the Bolivarian Revolution. Well, we don’t know exactly how many there are here on this side of the border, but it could be between a thousand and 2,000 combatants, but combatants with quite a bit of experience and very well armed. We also have the famous collectives, the Chavista paramilitary groups, which are also armed and we have criminal groups, many of them better armed, at least than the Police. And so, when you add all that up and think about a potential, a post-overthrow situation, let’s say if they manage to decapitate this government, there will come a period of a great deal of uncertainty.

Phil: Who’s going to guarantee Venezuela’s internal security? Who’s going to face this threat? Is the United States willing to enter with troops to guarantee security? And if so, how many are needed and for how long? Trump has always said he doesn’t want to get involved in another endless war. So I think that’s something they haven’t thought through very deeply. I’d be surprised if there were a finished plan to face that, because the version we hear from María Corina Machado is that there practically won’t be any resistance here, there won’t be any security problem because the people are going, all the people are going to take to the streets to dance and celebrate. And those who aren’t jubilant will leave or will be imprisoned. I think that’s a bit of a caricature of reality.

Eliezer: We’ll take a break and be back.

Eliezer: We’re back on El Hilo.

Silvia: Well, we’d like to put all this in the regional context as well, because of course, the attacks on Venezuelan boats have been the most media-covered, but the United States has increased its military presence in other parts of the Caribbean. As we were saying, right? In this second Trump administration, his administration declared several drug trafficking groups as terrorist organizations, and on Thursday, October 2nd, Trump told Congress that the country was formally in armed conflict with the cartels. Do you think they’re somehow taking the war on drugs, which has been going on for so many years in Latin America, to another level?

Phil: Yes, definitely. They intend to turn it from metaphor into reality, into real war.

Phil: It’s obvious, let’s say, from long before Trump’s return to power. That many on Trump’s team, what they want is… what they think about drug trafficking is that the way to confront it is militarily. Sending drones, sending special forces to other countries’ territory. Now, the first country in their sights has been Mexico. And its president, Claudia Sheinbaum, has been emphatic in that regard, that she won’t allow it.

Archive audio, Claudia Sheinbaum: The United States is not going to come to Mexico with the military. We cooperate, we collaborate, but there won’t be an invasion. That’s ruled out.

Phil: Seeing that. Seeing that it’s difficult and for many other reasons, because the Mexico-United States relationship is a very complex relationship, it’s easier to carry out what they intend to do here in Venezuela, with the idea of sending a message to other countries and they surely plan to continue with this. But a lot will depend on how things go for them in this theater. Of course, they’ve achieved a temporary halt of drug flow from Venezuela through the Eastern Caribbean. It’s logical, nobody wants to take out a speedboat right now with drugs or even suspected of having drugs, knowing it’s suicide. So, for now that flow is stopped. But in drug trafficking, drug traffickers are very adaptable and have many resources, a lot of money, a lot of drugs, many weapons and other routes.

Phil: And the region? Well, some agree and have said so publicly, some U.S. allies: Argentina, Ecuador, for example, have declared their support for this policy. Trinidad and Guyana, very close neighbors, are even more enthusiastic, right? Even offering territory, their territory, for any armed action in the event there’s aggression from Maduro, something that I think he’s going to try to avoid at all costs. But in general the region has a dilemma because they know what Trump is like, they don’t want another fight with Trump, they don’t want to defend Maduro or drug trafficking either. So… I mean, obviously there have been public disagreements. Petro in Colombia, of course, first and foremost.

Archive audio, Gustavo Petro: The gringos are in deep trouble if they think that invading Venezuela will solve their problem.

Phil: And Lula also used his speech at the United Nations to criticize this type of policy.

Archive audio, Brazil news: And there are also movements to pay attention to: Brazil has sent 10 thousand soldiers to the border with Venezuela.

Phil: But they won’t do anything. I mean, nobody’s going to come out to defend Maduro. Perhaps a little, there will surely be statements expressing disagreement, but nothing practical to help Maduro, much less to defend him.

Silvia: You’ve mentioned Colombia and it seems to me it’s an important actor in all this, right? for being Venezuela’s neighbor, but also for its relationship with the United States and that last month the Trump government removed Colombia’s certification in the fight against drug trafficking. What does it mean that Colombia has lost that and what’s the United States’ justification for doing it? And if it relates to this strategy or U.S. policy in the region.

Phil: Well, the Trump government hasn’t made any secret of its disagreement with Petro. I mean, it doesn’t see Petro as an ally in any sense. They’re anxiously awaiting the end of Petro’s government which comes next year and they hope he’ll be replaced by a figure much closer to their point of view. Decertification, well, it’s always been, I mean, that’s debated annually in the United States because, obviously, it’s very difficult to declare that Colombia is doing everything possible to stop drug trafficking seeing the volume of drugs that comes out of there. And also the fact that there’s been a significant increase in drug production. But at the same time the United States has historically been the firmest ally and vice versa, right? Colombia is the United States’ firmest ally in the hemisphere. It’s received a great deal of military aid and of all types. If they had decertified Colombia without the accompanying waiver, as they say, the exemption that allows these programs to continue, the situation would be much worse for Petro and for Colombia.

Phil: But, it seems that the United States still understands that the problem with punishing Colombia is that you run the risk of destabilizing a government that has multiple problems in terms of, not only organized crime, drug trafficking, but insurgency. It would be stupid to destabilize Colombia. Even if you don’t like the current government, Colombia remains a democracy.

Phil: But of course, President Petro isn’t helping. Petro has said that an attack on Venezuela is an attack on Colombia and on the entire continent. And he’s intended to somehow fuse the Colombian Armed Forces with the Venezuelan ones. He intends that they share intelligence and such. And those things are not only inconvenient from a sensible, rational policy point of view, at this specific moment with the Trump government lurking, but it really doesn’t make any sense to intend to ally yourself that way with a government of the nature of what we have in Venezuela.

Eliezer: We’ll take one last break and be back.

Eliezer: We’re back.

Silvia: Well, returning to Venezuela. You’ve lived there for almost 30 years. What’s the atmosphere like? Are people afraid, are they worried that the United States is going to invade the country or something like that? What is, like, the atmosphere there?

Phil: If you came here, right now, to Caracas and without knowing anything about this, you might not even notice. People have to go on with their daily lives. We have an extremely bad economic situation. Most people live in poverty. People have to work and try to earn enough to feed themselves, etc. The other thing I think is important to understand is that information here is scarce. The mass media are either in the government’s hands or intimidated. Many people don’t have much information about what’s happening, except the information the government gives them. Certainly there are very nervous people, especially those who have been government supporters, or have been officials, or continue to be officials. Then there’s a group, certainly… It’s very difficult to know how many there are, because here polls have practically stopped coming out publicly. But yes there are people who are enthusiastic, who want the American military to come, who honestly believe that this will end the problem and that everyone will live happily ever after. After that I think in the middle there are many people who mock, who laugh at the situation, who believe it’s just another bluff or who are simply waiting to see what happens. And one who, well, tries to analyze it, always gets the questions, right? I mean, what’s going to happen, right? Is this serious? I mean, are the marines going to arrive? And well, one tries to respond in the best way possible.

Silvia: And how do you respond? I mean, does it worry you, for example, to hear Trump say that they could take the attacks on drug trafficking from the sea to inside Venezuelan territory? I mean, do you think he’s paving the way for a possible invasion or regime change as Marco Rubio would want?

Phil: I started like many I think, about a month and a half ago when this began, my first impression was oh, it’s another bluff, we’ve seen it before, right? It’s another phase of maximum pressure and when the fleet leaves, Maduro is going to still be in power. With the days, with the increase in force, and the increasingly heated rhetoric, every day it seems less like a bluff and more real.

It’s increasingly difficult to think that all this is simply a very expensive bluff, I don’t know whether we’re talking about 50-50 odds, if now it’s more likely that… We know they continue evaluating their options. So I don’t think the decision has been made yet either, but now… I mean, if we start hearing explosions in Caracas, I think obviously it’s going to be dramatic, but not so surprising because it already seems that’s what they intend, it’s what they declare that, practically, they’re going to do. I don’t know if it’ll be here in the capital, I don’t know what they intend, or if the intention would be to do it all at once or escalate gradually to give Maduro the impression that yes they’re coming for him and convince him that he has to leave the country, we don’t know. But some military action on land I think is now more likely than not.

Eliezer: This week, Donald Trump ordered Richard Grenell, the special envoy from the White House to Venezuela, to suspend all diplomatic contact with the country, including conversations with Maduro. Additionally, the U.S. Department of Justice approved the use of lethal force against a secret list of drug cartels.

Silvia: The Democratic Party introduced a motion in the Senate to block military attacks in the Caribbean, but it was rejected. And in Colombia, Gustavo Petro said that the last speedboat bombed by the United States was from his country and carried Colombian citizens.

Mariana: This episode was produced by me, Mariana Zúñiga. It was edited by Silvia and Eliezer. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design and music are by Elías González.

The rest of El Hilo’s team includes Daniela Cruzat, Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo, Natalia Ramírez, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El Hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent and rigorous journalism, we ask you to join our memberships. Latin America is a complex region and our journalism needs listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar and help us with a donation.

If you want to go deeper into today’s episode, subscribe to our email newsletter by going to elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it out every Friday.

You can also follow us on our social networks. We’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook and Threads. You can find us as @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share the episodes.

Thanks for listening.