Ecoansiedad

Salud mental

Crisis climática

Calentamiento global

Desastres climáticos

Solastalgia

Los efectos de la crisis climática se sienten cada vez más cerca. Y es difícil ignorar las noticias sobre la trayectoria en la que vamos: hacia un planeta cada vez más caliente y con fenómenos meteorológicos cada vez más extremos. Esta semana hablamos con tres periodistas que han investigado cómo estos cambios afectan nuestra salud mental. Primero, Yanine Quiroz de Carbon Brief nos cuenta su experiencia con la ecoansiedad, un miedo intenso a desenlaces catastróficos. Luego, Alejandra Cuéllar, editora del medio Dialogue Earth, y Mónica Monsalve de la sección América Futura del diario El País, nos explican las secuelas psicológicas que dejan los desastres climáticos y la pérdida gradual del territorio. Alejandra y Mónica entrevistaron a expertos, revisaron estudios y escucharon las historias de personas afectadas por la crisis climática para entender los retos que enfrentamos en América Latina y qué podemos hacer para mitigar la ecoansiedad.

Créditos:

-

Producción

Silvia Viñas -

Edición

Eliezer Budasoff -

Verificación de datos

Desirée Yépez -

Producción en redes sociales

Samantha Proaño, Melisa Rabanales, Diego Corzo -

Diseño de sonido y mezcla

Elias González -

Música

Elías González, Remy Lozano -

Tema musical

Pauchi Sasaki -

Fotografía

Getty Images / Luis Robayo

Etiquetas:

Transcripciones:

Transcripción:

Silvia Viñas: Lo primero que te voy a pedir porfa es que te presentes.

Yanine Quiroz: Yo soy Yanine Quiroz. Tengo 33 años y vivo en Ciudad de México. Soy periodista y trabajo para el medio de comunicación Carbon Brief, que se especializa en comunicar temas de cambio climático y medio ambiente.

Silvia: O sea, estás básicamente casi todo el día pensando en el clima y en el medio ambiente.

Yanine: Sí, definitivamente es parte de mi día a día.

Silvia: ¿Y cuándo empezaste a sospechar que la crisis climática estaba afectando tu salud mental?

Yanine: Yo creo que si bien desde antes de que trabajara, ya cuando estaba terminando la carrera de periodismo en la universidad, los problemas ambientales y de cambio climático sí me afectaban de cierta forma porque me preocupaban. Una vez que salgo de la universidad y empiezo directamente ya a trabajar más estos temas de cambio climático y ambiente, en ese momento, fíjate Silvia, estos temas no me habían afectado tanto a nivel emocional porque hasta cierto punto yo ya estaba acostumbrada a ver esas noticias todo el tiempo, o incluso a escribir sobre ellas. Pero, fue precisamente el año pasado cuando empecé a notar que había resurgido en mí esa ecoansiedad que yo sentía que tenía de más joven, cuando estaba en la universidad y me preocupaban esos problemas. Justamente coincidió que el año pasado en México vivimos una serie de ondas de calor.

Audio de archivo, presentador: Diez ciudades tuvieron su día más caluroso de la historia.

Audio de archivo, periodista: Son 26 personas ya quienes han perdido la vida a consecuencia del golpe de calor y también de la deshidratación.

Audio de archivo, periodista: Se pronostica que el termómetro registre temperaturas superiores a los 45 grados en varias zonas del país.

Yanine: Además, no había llovido en mucho tiempo y estábamos enfrentando una escasez de agua importante. Entonces yo era algo que notaba que cada vez se venía más cerca, o sea que era un problema cada vez más cercano. Parte de mi rutina es monitorear noticias ambientales de México, de Latinoamérica, pero también del resto del mundo. Pero al mismo tiempo era vivirlo en carne propia, porque era un calor insoportable, que incluso habían días donde yo sentía tanto ese calor abrasador en en donde vivo, que en realidad es un lugar, yo podría decir fresco, pero era un calor que incluso no me permitía trabajar. Había veces donde me tenía que ir a dormir, cosa que nunca hago. O sea, yo nunca duermo en el día, pues ese calor me hacía tener que ir a dormir porque no podía ni siquiera concentrarme. Además de lo que yo vivía personalmente, por supuesto que yo escuchaba a conocidos, a parientes, amigos, a vecinos que se quejaban mucho del calor, de la falta de agua que ya se estaba viendo en ciertas partes de la ciudad. Entonces todo eso más mi trabajo, como que me hizo caer, de verdad, yo pienso que en esos momentos yo creo que era una depresión la que llegaba a tener, porque de verdad sentía como cada vez más desesperanza. Y empecé a tener igual mucho miedo.

Silvia: Bienvenidos a El hilo, un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Soy Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer Budasoff: Y yo soy Eliezer Budasoff. Los efectos de la crisis climática se sienten cada vez más cerca. Y es difícil ignorar las noticias sobre la trayectoria en la que vamos… hacia un planeta cada vez más caliente y con fenómenos meteorológicos cada vez más extremos.

Hoy, cómo esta crisis afecta nuestra salud mental, los retos que enfrentamos en América Latina para reconocer el problema, y qué podemos hacer para mitigar la ansiedad que nos causa ver y vivir la crisis climática.

Es 18 de abril de 2025.

Silvia: Tú usaste la palabra ecoansiedad y creo que vale la pena definirla. ¿Cómo la definirías?

Yanine: Ecoansiedad la defino como precisamente estos sentimientos de ansiedad y que ansiedad es como una preocupación por el presente y sobre todo por el futuro. Es una preocupación exacerbada. O sea, eso es algo que ya no podemos controlar, que realmente influye mucho en nuestras vidas diarias, que a veces no nos permite vivir bien, vivir de manera libre, tranquila y hacer nuestras actividades, sino que es un pensamiento que se entromete en tu día a día y te causa miedo. Y ese miedo puede ser paralizante. O sea, puedes de plano no hacer nada, quedarte en ese abismo de miedo sin querer o saber qué hacer para responder y disminuir esa ansiedad.

Eliezer: Tal vez ya han escuchado esta palabra, sobre todo si tienen hijos o amigos con hijos que están en escuela primaria o son adolescentes. La ecoansiedad es algo que puede sentir una persona que está expuesta directamente a problemas ambientales, como ríos contaminados, o que vive con los impactos del cambio climático… olas de calor, por ejemplo. Pero también puede afectar a gente que ve noticias sobre la crisis climática.

Yanine: También pueden llegar a sentir esa eco ansiedad que básicamente sí es un miedo intenso a desenlaces catastróficos, pesimistas, fatales por estos problemas ambientales y climáticos.

Silvia: Sí, yo lo que he sentido a veces es como: OK, yo siento que estoy tratando de hacer algo por esto. Reciclo, trato de no comprar tanta ropa nueva, compro de segunda mano, no sé, uno trata de hacer como estas cosas un poco para sentir que está haciendo algo. Y después, claro, ves las noticias y es como: No, el año más caliente la historia. Y cosas así, que piensas… O sea, yo lo que he sentido es un poco de desesperanza. No sé si eso también es parte, de cómo sentir: no hay marcha atrás. ¿Eso es parte de la ansiedad también?

Yanine: Sí, definitivamente es parte de esos sentimientos que te da realmente de sentir desesperanza por lo que se está viviendo y por lo que se puede presentar en el futuro. De hecho, tuve la oportunidad de hacer un reportaje para la revista Nexos aquí en México, donde abordábamos cómo la ecoansiedad está afectando a las mujeres jóvenes mexicanas al momento de decidir si tener o no hijos en el futuro.

Eliezer: A finales del 2021, Yanine hizo una encuesta a más de cien mujeres mexicanas. Para el 78%, la crisis climática era un factor que consideraban a la hora de tener hijos. Un cuarto dijo que las había llevado a no querer tenerlos. Y más de la mitad dijo que era una de las razones.

Silvia: Hay otros estudios que apuntan a lo mismo. Uno de 2021 dice que 5 de cada 10 jóvenes en Brasil dudaba sobre tener hijos por la crisis climática; en Chile, otro estudio daba una cifra de 7 de cada 10.

Yanine: Para mí eso ya es como… O sea, ¿hasta dónde podemos llegar con la ecoansiedad? De verdad la ecoansiedad tiene manifestaciones que sí influyen mucho en la vida de las personas o pueden llegar a influir mucho.

Silvia: Acabamos de escuchar a Yanine Quiroz y su experiencia con la ecoansiedad. Cuéntenos qué tan común encontraron que es este tipo de ansiedad y a quién afecta más.

Alejandra Cuellar: Bueno, la ecoansiedad es un fenómeno interesante porque es reciente, ¿no? Que se utiliza esta palabra. Es como desde el 2017 que se empezó a utilizar desde la Asociación de Psicología en Estados Unidos.

Eliezer: Ella es Alejandra Cuéllar, editora del medio Dialogue Earth.

María Mónica Monsalve: Lo difícil de esto también es que no es que tú vayas a terapia y el psiquiatra o el psicólogo te diga si lo tuyo es ansiedad.

Silvia: Y ella es María Mónica Monsalve, periodista de la sección América Futura del diario El País. Juntas hicieron una investigación sobre el impacto del cambio climático en la salud mental.

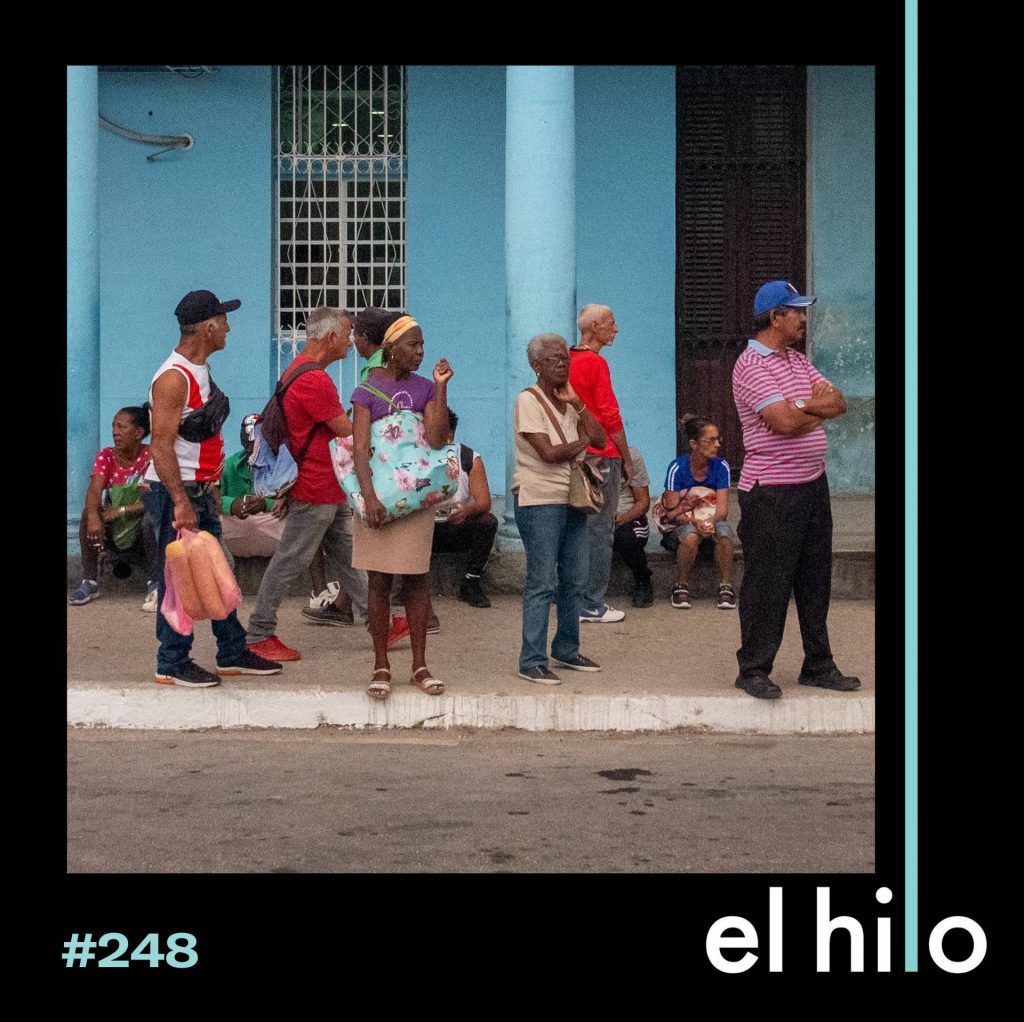

Alejandra: Salimos a las calles a hablar con gente en distintos países en América Latina. Y lo que encontramos es que la verdad es que es un fenómeno que uno, uno pensaría que está asociado tal vez a las clases más privilegiadas que tienen acceso a las noticias, pero la verdad es que lo siente la gente en todas las clases sociales, porque están expuestas a estos cambios del clima. Entonces por ejemplo, en Ciudad de México yo vi a personas muy jóvenes que estaban muy angustiadas y con mucha ansiedad frente a las olas de calor, porque ya no pueden practicar deportes como lo hacían antes. ¿Sabes? Entonces son ejemplos que tú dices, claro, están sufriendo de ansiedad porque ya les está afectando como sus quehaceres. Entonces es interesante que es bastante amplio y en América Latina no se conoce tanto.

María Mónica: Luego, lo que sí es súper evidente que pasa en Latinoamérica es que no se está estudiando tan juiciosamente la relación de cambio climático y salud mental. La mayoría de la literatura científica, sobre todo, o de los estudios, se están haciendo como en los países que consideramos de ingresos altos o lo que llamamos a veces el norte global. Y acá no se ha explorado tanto eso. Digamos, nosotros nos encontramos con un estudio que salió en el British Medical Journal en 2021, que trataba de ver que se ha estudiado de la relación de salud mental y cambio climático en países de ingresos bajos y medios, y ellos encontraban que solo habían 58 estudios en 11 países y solo cuatro eran de América Latina. Es decir, están como surgiendo semillitas de gente de distintas partes, de distintos campos de estudio que están haciéndose esta pregunta, pero no está como este ecosistema todavía creado en América Latina y el Caribe.

Silvia: ¿Y por eso es que les pareció importante cubrir la conexión entre la crisis climática y la salud mental en América Latina, por esta falta de información?

Alejandra: Y yo te diría que de ahí surgió todo. O sea, nosotras, tanto Mónica como yo, somos periodistas medioambientales, entonces estamos expuestas a estas noticias diario estamos leyendo qué está pasando, los distintos fenómenos climáticos, los desastres climáticos y yo, personalmente, recuerdo que tuve un día en donde después de leer noticias me sentía la verdad súper, súper, súper triste, con una desesperanza muy grande, así como que ya no quiero hacer nada. O sea, como decimos en Colombia, apaga y vámonos porque está muy fuerte este fenómeno. Y yo decía, en mi medio hablamos del tema ambiental, pero no hablamos de las emociones alrededor de esto. Entonces ahí fue que justo nos encontramos con Mónica, ella tenía la misma preocupación y dijimos, cuando conversamos, dijimos, bueno, nosotras sentimos esto, ¿quién más lo estará sintiendo? ¿Sabes? Porque una de las cosas que vimos es que hay mucha soledad frente a la ansiedad y frente a los temas de salud mental que tú estás sintiendo. Un trastorno, una tristeza, una una cosa que es incómoda. Dices, me siento muy sola, me siento muy solo porque soy la única persona que lo siente. Entonces, como decimos, bueno, somos periodistas, tenemos la capacidad de meternos a este tema, investigar a quién más le está pasando, de qué manera y un poco abramos la conversación, ¿no? Como de este fenómeno.

Silvia: Yanine nos contaba sobre las olas de calor que tuvieron en México el año pasado y cómo eso afectó su salud mental. Estas olas pasan cada vez más en muchos países, pero también estamos viendo más desastres naturales que son más frecuentes y más devastadores por la crisis climática. ¿Cómo afectan estos desastres nuestra salud? ¿Qué encontraron en su investigación?

Alejandra: Bueno, nosotras empezamos a mirar específicamente ese tema porque es donde hay más investigación. También miramos el fenómeno de Otis, que fue este huracán que pasó en el 2023 en México, que afectó a Acapulco.

Audio de archivo, periodista: La ciudad del sol, la perla turística de México venida a menos en la ultima década, es un caos.

Audio de archivo, mujer: Toda la gente está frustrada, desesperada.

Audio de archivo, periodista: Mucho dolor por reparar, muchas lecciones que aprender y todo por reconstruir.

Alejandra: Fue un huracán tipo cinco y tomó a la población desprevenida. Entonces fue un buen ejemplo para mirar, bueno, cómo se está reaccionando. Y encontré que Médicos Sin Fronteras sí tuvo una intervención en salud mental. Entonces hablé con la encargada que se llama Betzaida López y ella lo que me contó fue que efectivamente llegaron como días después del desastre y lograron hablar con muchas personas. Algo interesante es que en los desastres naturales, todo se vuelve de difícil acceso. Las calles estaban cerradas. Entonces fueron con una clínica móvil que llamaban, como con una camioneta especializada para esto, y hicieron una intervención en salud y salud mental. Entonces, por ejemplo, si alguien estaba con un tema físico, también le preguntaban: Oye, ¿tú cómo estás? ¿Cómo te sientes? Y lo que decía es que en estos primeros momentos la gente está muy, muy afectada con el desastre. Entonces tienen flashbacks. Si hay un viento muy fuerte, vuelven a vivir lo que ocurrió. Hay pesadillas. Los niños y las niñas están muy afectadas. Entonces, la verdad es súper importante que exista esta intervención. Otra cosa interesante fue que la verdad la mayoría de las personas que decidieron aceptar esta ayuda eran mujeres. Entonces ella me dijo, los hombres por lo general no reciben la ayuda. Hay mucho estigma. Dicen yo no estoy loco, yo no necesito esta ayuda. O sea, como que lo primordial es la salud, es lo físico. Se perdió mi casa. No me hables de emociones ahora.

Eliezer: La intervención en salud mental cuando hay desastres climáticos es bastante reciente. Alejandra nos explicó que después del terremoto de 2011 en Sendai, Japón, donde murieron unas 19,000 personas, la ONU creó lo que se llama el Marco de Sendai para la reducción del Riesgo de Desastres.

Alejandra: Y ahí se adoptaron, digamos, estos marcos que es de intervención en salud mental, porque se encontró que las personas que viven un desastre climático viven este trauma y no se atienden, después pueden desarrollar temas de ansiedad, depresión, comportamientos suicidas, abuso de sustancias, mucho alcoholismo. Entonces desde ahí fue que se integró para desastres climáticos. Como, oye, es importante que veamos la salud mental de las personas también, porque eventualmente se puede convertir en un problema más grande.

Silvia: Alejandra dice que la intervención en Acapulco fue pequeña. Unas 130 consultas. Pero también capacitaron a la población, para poder atender problemas de salud mental ellos mismos… Porque Médicos Sin Fronteras y otros profesionales que van para ayudar justo después de la emergencia, en algún momento se van.

Alejandra: Y son a veces comunidades de muy bajos recursos. Y entonces es importante dejar las capacidades entonces que, por ejemplo, si alguien presenta un cuadro de ansiedad o de suicidio, no traten a esa persona como este loco esta loca, no, y lo rechacen, sino que más digan, más bien digan, ya tengo una herramienta para reconocer que esta persona está teniendo un problema de salud mental. Ya tengo a lo mejor una vía para decir mira, puedes llamar a este número, vamos a una consulta o nos movemos de otra forma. Entonces eso es súper importante porque es como dejar las capacidades en las mismas comunidades y que se empiece a desestigmatizar este tema.

Silvia: Claro, ¿ustedes hablaron con alguien afectado por Otis?

Alejandra: Sí, hablamos con Diana Ruiz. Diana Ruiz es una mujer de 35 años. Ella y su madre vivieron el huracán. Lo que ellas cuentan es que estaban totalmente desprevenidas. Las agarró en su departamento. No alcanzaron a guardar las cosas. Lo tuvieron que vivir dentro del baño, agarrándose de la puerta mientras el viento soplaba. Como que describen que las paredes se estaban cayendo por pedacitos y había mucha fuerza. Y los ruidos. O sea, la verdad fue un temor muy grande. Estaban como en un modo de urgencia y de supervivencia, ¿no? Como de salvar su casa. ¿Qué pasó? La puerta se cayó. Ella tenía una tienda, todo se echó a perder, y al otro día era pues a revisar el daño y también como a revisar el tema de ladrones, de que no entraran, ¿no? Y Diana me contó, digamos, yo hablé con ella varios varios meses después de lo ocurrido, es que las emociones ya más fuertes llegan después del hecho, ¿no? Como después de que ya pasó el huracán. Como estas emociones de tristeza, de pérdida, ¿no? como de angustia también. La verdad es que en la actualidad Acapulco no se ha podido recuperar al 100% de ese desastre natural. El shock económico ha sido muy grande. Ellas tuvieron que hacer un cambio de ubicación. Se tuvieron que ir a vivir a Ciudad de México porque no… la situación no era sustentable allá, en Acapulco. Y nada, o sea, la situación de salud mental continúa, ¿no? Es afrontar muchas cosas a la vez y han recibido atención. Pero lo que uno ve con ese ejemplo es que no es suficiente.

Eliezer: Una pausa y volvemos.

Silvia: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo. Alejandra y María Mónica querían abordar diferentes formas en las que se ve esta relación entre la salud mental y el cambio climático. Está la que tocamos recién: hay un desastre climático, como el huracán Otis, y eso deja secuelas psicológicas, como estrés postraumático, depresión, ansiedad…

Eliezer: Pero descubrieron que también se está empezando a ver cómo los cambios más progresivos, más lentos, tienen un impacto en las personas.

Silvia: En su investigación ustedes hablan de la salud mental de las personas que ven cómo el paisaje que conocían, el territorio en el que crecieron, se pierde por la crisis climática. Cuéntenos sobre la joven mujer indígena que ustedes entrevistaron, que pasó por esto.

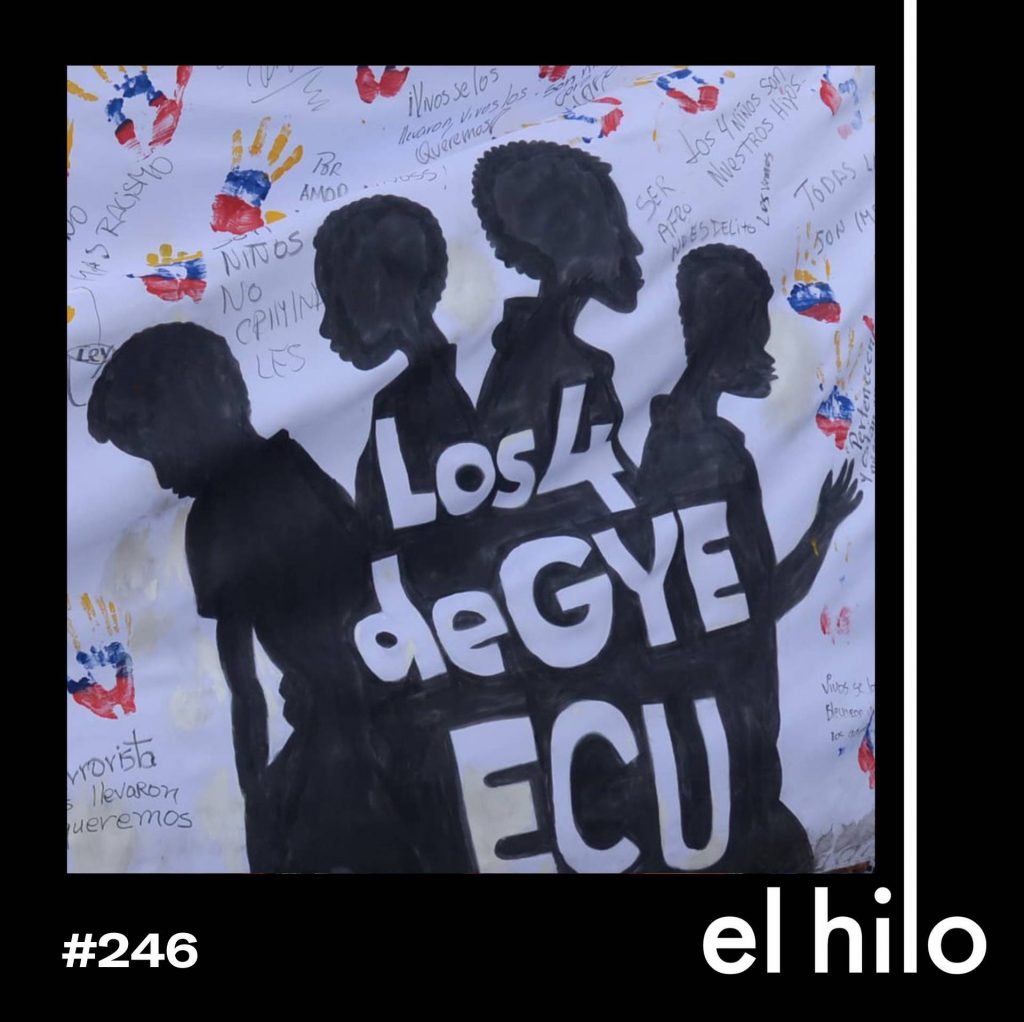

María Mónica: Sí, se llama Regeane Oliveira. Ella es indígena terena. Y ella hizo parte de un estudio que hizo un investigador también de Brasil, que se llama Antonio Grande, que quería explorar como tanto las sensaciones como lo que piensan los indígenas frente a la salud mental y el cambio climático. Entonces lo que ella contaba un poco es que ella al salir como de su comunidad y llegar a una ciudad, porque ella precisamente además está estudiando medicina, ese desarraigo, o sea, ese hecho de salir de una comunidad donde ya lo que cuenta es podía caminar tranquila, podía montar en bicicleta. El aire era rico, lo que comía, incluso, cambia. Entonces ese desarraigo le genera a ella unos procesos de ansiedad muy fuertes. Incluso gana un montón de peso por el cambio de la dieta. Y cuando regresa progresivamente no se a visitar a su familia o visitar a tu mamá, se empieza a dar cuenta que ese paisaje y ese territorio también lo están transformando. Y eso. Entonces, claro, en vez de volver a la casa, sentir como ahí volví a mi casita, a mi paisaje, a lo de siempre, es uf, volví y esto ya no es lo mismo. Ella contaba que los ríos efectivamente habían algunos que se estaban secando, otros que habían sido desviados y eso también le genera a ella un una sensación de como de dolor, de duelo quizás.

Eliezer: Hay una palabra para este sentimiento: solastalgia. La creó un filósofo, Glenn Albrecht, en 2005 en Australia, después de ver las emociones que sentían los pobladores que veían cómo su paisaje se estaba transformado por la minería.

María Mónica: Y creo que es, o sea, la palabra no es linda, o sea, es linda conceptualmente no es linda que suceda porque es muy fuerte, pero es el duelo. Entonces, claro, uno hace duelo cuando le dicen estás haciendo un duelo, cuando se te muere tu papá, tu mamá y cuando uno acá lo que llamamos en Colombia la tusa, que es cuando uno termina con una pareja y estás haciendo un duelo porque perdiste un amor, o la posibilidad de ese amor. Y luego pensar como que nosotros como humanos también hacemos duelos y nos duele literalmente en el corazón, en el alma, en el intestino o donde quieran ubicar las emociones ustedes que se pierde un paisaje. Y pues la razón por la que Antonio Grande, que es el líder de este estudio, hizo esto, es porque se está viendo que la salud mental de las poblaciones indígenas en general alrededor del mundo es está teniendo muchos riesgos, no solo por el cambio climático, sino porque usualmente son poblaciones marginadas, estigmatizadas, que no les llegan recursos de salud mental. En ese estudio ellos hablan que el suicidio es la segunda causa de muerte de los indígenas entre los 15 y los 29 años. Entonces, de nuevo es como ya es una población, digamos, vulnerable en temas de salud mental por ciertas cosas ajenas al cambio climático. Y luego llega el cambio climático y les… Como que les revienta aún más ese esos temas.

Silvia: Si ellos tienen una relación con la tierra, con la naturaleza como muy especial, y me parece súper interesante que este estudio vea específicamente cómo los afecta a ellos, porque obviamente va a ser diferente que a nosotros.

María Mónica: Sí, exacto, porque como ellos también no tienen como esto tan antropocentrista de que el humano y luego la naturaleza, sino los seres, los seres somos todos y el árbol es un ser y el río es un ser y el nevado es un ser, entonces en la medida que tú los estás afectando, están afectando a gente o a seres paralelos que están en tu mismo nivel. Entonces, claro, eso, si uno lo piensa, es muy fuerte esa pérdida. Es como la pérdida de un ser humano para, quizás, para ellos.

Silvia: ¿Y en esta investigación qué proponen para ayudar específicamente a los indígenas?

María Monsalve: Sí, pues, esta investigación habló con 20 indígenas que estaban estudiando en dos universidades de Brasil. Lo que hacen es preguntarles ¿Qué se puede hacer para que la salud mental indígena se mejore en el cambio climático? Ellos lo que hacen es empezar, pues cada indígena a sus ideas. Luego hacen como un unas afirmaciones, unos mapas y entre lo mejor ranqueado como lo mejor ubicado está el tema de conservar el territorio indígena, que además es muy lindo en la medida en que no solo es en temas de salud mental, sino también en temas de cambio climático y biodiversidad. La ciencia también ha dicho lo que mejor podemos hacer es reconocer, titular y conservar esos territorios. Y ellos también dicen, esto nos ayudaría. Conservar y reconocer las tradiciones y saberes indígenas. Y luego ya también hablan de políticas públicas, ¿no? Que lleguen políticas públicas de salud mental y salud obviamente física a los territorios indígenas donde muchas veces no llegan bien.

Eliezer: Vamos a hacer otra pausa, y a la vuelta hablamos con Alejandra y con María Mónica sobre los retos que enfrentamos en América Latina para abordar los efectos de la crisis climática en nuestra salud mental.

Silvia: Y Yanine Quiroz nos cuenta qué hace ella para cuidarse. Ya volvemos.

Eliezer: Estamos de vuelta en El hilo.

Silvia: Ustedes nos contaban que, claro, si vas al psicólogo en Latinoamérica, o yo creo que en otros lados también, te van a hablar de ansiedad en general, no específicamente de ecoansiedad. Entonces, claro, eso es un reto. ¿Además de eso, qué retos enfrentamos en América Latina para poder abordar la salud mental desde el lente de la crisis climática?

Alejandra: Pues yo creo, esto es algo yo creo que tú ni siquiera necesitas un estudio para saberlo, ¿no? Vivir en América Latina nomás te das cuenta que el tema de acceder, por ejemplo, a un psicólogo, es algo que recientemente se ve como normal, ¿no? O sea, la salud mental en América Latina ha tenido un estigma muy grande. Yo, de hecho, cuando le comenté a una amiga en Colombia sobre esta investigación de la salud mental me decía, en Colombia te dirían coja oficio, ¿no? Como no hay tiempo para estos temas, no, como no es lo primordial, no es lo más importante. Y es lo mismo que veíamos que te comentaba con el tema de género en la ocasión de Otis, que es de los hombres diciendo yo no estoy loco, yo no necesito esto, no, esto es de alguien más. Yo no necesito esta ayuda, encontrarle un sitio a esto. Lo que es interesante, ahora que lo veo, es que una de las cosas que describen en algunos estudios es que cuando hay desastres, las comunidades mismas ya tienen herramientas para lidiar con salud mental, pero que no son reconocidas como dentro de la escuela de psiquiatría o psicología. Entonces a lo mejor hay muchas herramientas locales que ya existen, pero que hay cierta resistencia a a querer pensar que son salud mental, ¿no? Entonces salud mental que es psiquiatría, psicología y la comunitaria es otra cosa, pero al final es hablar de las emociones, ¿no?

María Mónica: Sí, y y pues a pesar de eso, es decir, efectivamente el tema comunitario es muy importante. Pero el reto también desde los gremios de salud es enorme, claro. Es decir, por ahí hay un reto por los educadores, no sé, los niños en los colegios, cómo estamos educando a los niños más pequeños para entender el cambio climático sin generarles, quizás, como se dice, como la negatividad que que a veces Aleja y yo reconocemos en nosotros de esto ya pa qué hacemos nada de esto, ya nos fuimos al carajo. Entonces cómo crear niños que que no que no ignoren estos temas. Pero pues que tampoco les estemos diciendo a los siete años como oye, mira, ya esto se acabó.

Alejandra: Creo que es súper importante lo que dice ella es, sí, efectivamente, cómo estamos criando las poblaciones jóvenes. Creo que eso es un punto mega importante y que la de que los profesionales no estamos capacitados para hablar de emociones ni para hablar del contexto. También otra cosa interesante es que esto lo vimos de Good Energy Stories, que es un medio que está generando información al respecto de salud mental y cambio climático, es que reconocer esta angustia o esta ecoansiedad es importante que no es necesariamente una cosa negativa, ¿no? Sino que es una respuesta razonable a una amenaza global de escala sin precedentes, ¿no? Es súper comparable, por ejemplo a la a la angustia que la gente sintió durante la pandemia, y a lo mejor es algo que también puede movernos de nuestra comodidad para hacer otro tipo de acciones.

Silvia: Sobre eso les quería preguntar porque me pareció interesante las soluciones que ustedes encontraron para reducir esta ecoansiedad. Es como que se crea un círculo virtuoso, ¿no? Cuéntenos un poquito sobre eso.

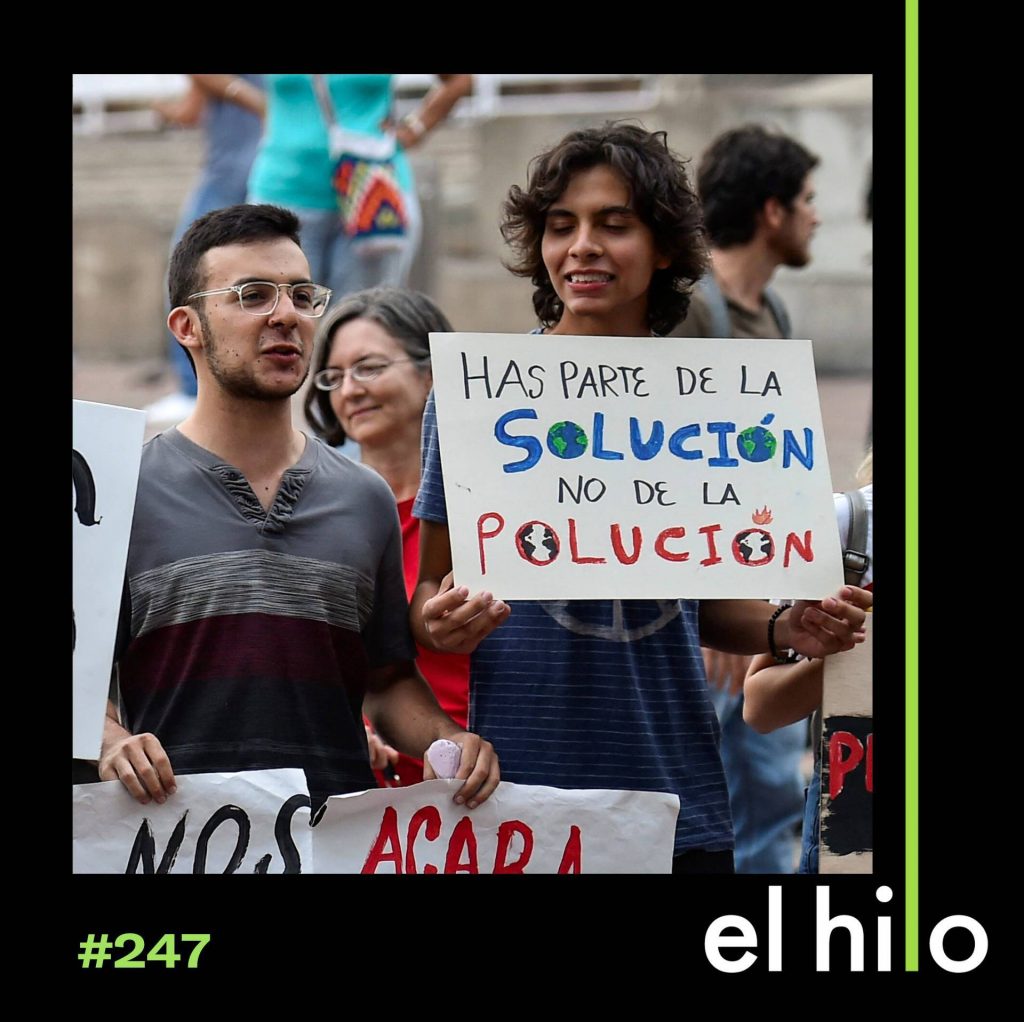

María Mónica: Sí, pues, básicamente, lo que nos decían en general los psiquiatras, psicólogos y gente comunitaria que se que se está metiendo en este tema es: actuar. Que suena súper obvio, es que al final no lo hicimos como entonces, ¿que quieres que apague la luz? ¿Que plante un árbol? Sí, como que súper actuar, pero claro. Es decir, obviamente estas acciones lleva, no sé, ir a una manifestación, exigirle a mi gobierno que sea más fuerte con estos temas no va a cambiar el cambio climático a la escala global, que es que son unas acciones enormes. Pero como yo lo veía, es como te salvas a ti mismo. Es decir, tú actuando le das como una paz mental, te das como un alivio mental que luego te va a dejar hacer mejores cosas.

Alejandra: Una de las cosas que me parecieron súper bonitas es que, claro, está el lado el lado de de sentirte que estás apoyando un problema y que estás como contribuyendo a la solución. Pero también está el hecho de que te estás juntando y que te estás asociando con otras personas que también están interesadas en esto. Y entonces lo que estás creando ahí es es creando otra idea de futuro. Yo eso lo que veo es súper interesante, porque la desesperanza y la ecoansiedad surge de estamos expuestos a miles de noticias de el apocalipsis climático, no? Las predicciones nos dicen que el planeta no va para ningún escenario positivo. De hecho, todo lo contrario, no? Se están acabando los recursos, el aire está cada vez peor. Entonces esta idea de futuro es como wow! O sea, mi futuro pinta muy mal, mi futuro pinta mi futuro pinta triste, desesperanzador. Y al yo incluirme, incorporarme, a una iniciativa grupal, estoy con personas y estamos diciendo espérate, el futuro a lo mejor lo estamos construyendo y lo estamos construyendo de otra forma.

Silvia: ¿Cuando tú buscaste ayuda, encontraste profesionales que hicieran la conexión entre la crisis climática y lo que estabas sintiendo?

Yanine: No. Me tardé un tiempo en darme cuenta o en reconocer que sí estaba sintiendo ecoansiedad.

Eliezer: De nuevo, la periodista Yanine Quiroz, a quien escuchamos al comienzo de este episodio.

Yanine: Pero sí fue al final donde al final de ese tiempo, de esas ondas de calor, donde sí dije es que esto no es… No fue normal. O sea, yo nunca había sentido eso por tanto tiempo y justamente al final pues empezó la temporada de lluvias. Y esas lluvias ayudaron a a que ya no sintiera tanto esa ecoansiedad.

Silvia: Yanine, aparte de la ansiedad relacionada con la crisis climática, tenía ansiedad generalizada por estrés. Se autoexigía mucho en el trabajo. Estaba con insomnio. Así que empezó a tomar antidepresivos y a tratarse con una psicóloga.

Yanine: Sin embargo, ella no es experta en ecoansiedad. Creo y creo que sí es algo que podría contemplar en el futuro. Si veo que que vuelvo a tener esos mismos síntomas, sí planeo como, tal vez, acercarme a gente que ya tenga más experiencia ayudando en estos temas de ecoansiedad, a pesar de que como te decía, yo he cubierto un poco un poco el tema de ecoansiedad anteriormente y en dentro de mis mis reporterías recuerdo muy bien lo que dicen los y las expertas, ¿no?, de cómo manejar esa ecoansiedad. Y a pesar de eso, o sea, creo que de todos modos seguiría necesitando la terapia, porque de verdad no es… Siento que hablar, siento que estar en terapia, de verdad, como que te sana un poco.

Silvia: Tú sigues dedicando tu tiempo a estas noticias. Puede que venga otra ola de calor o otra cosa, ¿no? Porque no sabemos qué viene. ¿Pero cómo te cuidas ahora, además de terapia, qué haces para cuidar tu salud mental?

Yanine: Muchas gracias por esa pregunta. Creo que es muy importante. Yo creo, y voy a ser honesta, o sea, te voy a compartir lo que yo pienso. Siento que estos temas de ansiedad, y en general problemas de salud mental, al menos en México, imagino que también en mucha parte de Latinoamérica, son afectaciones difíciles de abordar para quienes lo padecen, porque mucha gente padece esa falta de recursos que les permita acceder a este tipo de atención médica. Entonces yo pienso a veces que estoy en una posición de privilegio de poder solventar esos gastos. Y creo que ahí hay un tema bien importante de falta de acceso a esta atención psicológica para la mayoría de la población y creo que es bien necesaria.

Eliezer: Yanine dice que la terapia y las medicinas para la ansiedad han sido clave para ella. Pero también piensa en cambios directos. Por un lado, cuestiones prácticas de su vida cotidiana, como comprar un aire acondicionado para enfrentar futuras olas de calor sin que le afecten tanto, aunque sabe que eso también es un privilegio. Por otro, piensa en hacer cosas que sirvan para todos.

Yanine: También tengo en mente algo que he hecho anteriormente, cuando era más joven, que era ir a campañas de reforestación.

Silvia: Justo lo que nos contaban Alejandra y Mónica: tomar acción.

Yanine: Porque siento que ese es un una manera de hacer algo. Eso es definitivamente es algo que también quiero hacer, como regresar a ayudar, a ser parte del voluntariado. Creo que eso me ayudaría a sentirme también bien. Por supuesto, no nada más para mí, sino para todos. O sea, reforestar es una acción que es positiva para todos. Y creo que, yo diría que eso es ahorita lo que veo, como las opciones que que tomaría quizás encontrar algún terapeuta o leer un libro ya más especializado en ecoansiedad.

Silvia: Te agradezco mucho por tu sinceridad y por ser tan abierta en hablar de algo tan personal. Mi última pregunta sería. ¿Por qué? ¿Por qué estás dispuesta a hablar sobre esto? ¿Cuál es la importancia de de un poco darle voz a estas experiencias?

Yanine: Yo creo que porque es un o que son problemas, estos problemas de ecoansiedad, son problemas cada vez más frecuentes y que creo que van a seguir siéndolo y que podrían afectar a muchas más personas en el futuro. De hecho, ya lo está haciendo. Sin salud, sin salud mental, no podemos hacer realmente nada. O sea, no podemos vivir bien, no podemos trabajar, no podemos disfrutar la vida. Entonces es bien importante empezar a subir estos temas en la agenda de los medios, en la agenda pública. Es vital que empecemos a tomar en serio estos problemas que, si bien a lo mejor no les haya pasado todavía, que se considere eh como una parte del cuidado personal de cuidado mental de cada uno. Mhm. Y bueno, pues muchas gracias Silvia por por este espacio.

Silvia: Gracias Yanine.

Este episodio fue producido por mí. Lo editó Eliezer. Desirée Yépez hizo la verificación de datos. El diseño de sonido es de Elías González con música compuesta por él y Remy Lozano.

El resto del equipo de El hilo incluye a Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Nausícaa Palomeque, Bruno Scelza, Samantha Proaño, Natalia Ramírez, Juan David Naranjo Navarro, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, y Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón es nuestro director editorial. Carolina Guerrero es la CEO de Radio Ambulante Studios. Nuestro tema musical lo compuso Pauchi Sasaki.

El hilo es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Studios. Si valoras el periodismo independiente y riguroso, te pedimos que te unas a nuestras membresías. América Latina es una región compleja y nuestro periodismo necesita de oyentes como tú. Visita elhilo.audio/donar y ayúdanos con una donación.

Si quieres profundizar sobre el episodio de hoy, suscríbete a nuestro boletín de correo entrando a elhilo.audio/boletin. Lo enviamos cada viernes.

También puedes seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales. Estamos en Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook y Threads. Nos encuentras como @elhilopodcast. Déjanos allí tus comentarios y etiquétanos cuando compartas los episodios.

Gracias por escuchar.

Transcript:

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence and has been reviewed and edited by our team for accuracy and clarity.

Silvia Viñas: The first thing I’m going to ask you is to please introduce yourself.

Yanine Quiroz: I’m Yanine Quiroz. I’m 33 years old and I live in Mexico City. I’m a journalist and I work for the media outlet Carbon Brief, which specializes in communicating issues related to climate change and the environment.

Silvia: So basically, you’re thinking about the climate and the environment almost all day long.

Yanine: Yes, it’s definitely a part of my daily life.

Silvia: And when did you start to suspect that the climate crisis was affecting your mental health?

Yanine: I think that even before I started working, back when I was finishing my journalism degree at university, environmental and climate change issues already affected me in some way because they worried me. Once I graduated and started working directly on climate change and environmental topics, at that time, you know, Silvia, these issues hadn’t really affected me emotionally because, to a certain extent, I was already used to seeing those news stories all the time or even writing about them. But it was precisely last year when I started to notice that the eco-anxiety I had felt when I was younger, in university, was resurfacing—back when I was worried about these problems. It just so happened that last year, in Mexico, we experienced a series of heat waves.

Archival audio, presenter: Ten cities recorded their hottest day in history.

Archival audio, journalist: So far, 26 people have died due to heat stroke and dehydration.

Archival audio, journalist: The forecast predicts that temperatures will exceed 45 degrees in several parts of the country.

Yanine: Additionally, it hadn’t rained in a long time, and we were facing a significant water shortage. So, I started noticing that it was getting closer and closer, that it was becoming a more immediate problem. Part of my routine is monitoring environmental news from Mexico, Latin America, and also from the rest of the world. But at the same time, I was experiencing it firsthand—because the heat was unbearable. There were even days when I felt that scorching heat in the place where I live, which is usually a relatively cool area, but it was so intense that I couldn’t even work. There were times when I had to go lie down and sleep, which is something I never do—I never nap during the day. But that heat forced me to sleep because I just couldn’t concentrate.

Beyond my personal experience, of course, I was also hearing from acquaintances, relatives, friends, and neighbors who were complaining a lot about the heat and the lack of water, which was already affecting certain parts of the city. So, all of that—combined with my job—really made me fall into what I believe was a state of depression. I truly felt a growing sense of hopelessness. And I started to feel a lot of fear.

Silvia: Welcome to El hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. I’m Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer Budasoff: And I’m Eliezer Budasoff. The effects of the climate crisis are becoming increasingly tangible. And it’s hard to ignore the news about the trajectory we’re on: toward a planet that’s getting hotter and experiencing more extreme weather events.

Today, we’ll explore how this crisis affects our mental health, the challenges we face in Latin America in recognizing the problem, and what we can do to mitigate the anxiety that comes from seeing and experiencing the climate crisis.

It’s April 18, 2025.

Silvia: You used the word eco-anxiety, and I think it’s worth defining. How would you define it?

Yanine: I define eco-anxiety as these feelings of anxiety—where anxiety is a deep worry about the present and, above all, the future. It’s an overwhelming concern, something beyond our control that significantly impacts our daily lives. Sometimes, it doesn’t even allow us to live well, to live freely, peacefully, and to go about our activities. Instead, it’s a thought that intrudes into your daily life and causes fear. And that fear can be paralyzing. It can make you do nothing at all—trapping you in that abyss of fear without knowing what to do to respond or reduce that anxiety.

Eliezer: Maybe you’ve already heard this term, especially if you have kids or friends with kids in elementary school or teenagers. Eco-anxiety is something that can affect people who are directly exposed to environmental problems, such as polluted rivers, or the impacts of climate change: heat waves, for example. But it can also affect people who simply consume news about the climate crisis.

Yanine: They, too, can experience eco-anxiety, which is essentially an intense fear of catastrophic, pessimistic, or fatal outcomes due to environmental and climate issues.

Silvia: Yeah, what I’ve felt at times is like, OK, I feel like I’m trying to do something about this. I recycle, I try not to buy too many new clothes, I buy second-hand… You know, you try to do little things to feel like you’re making a difference. But then, of course, you see the news and it’s like, nope, this was the hottest year in history. Things like that. And I think, well, there’s no turning back. Is that part of this anxiety, too?

Yanine: Yes, that feeling of hopelessness about what’s happening and what’s coming is definitely part of it. In fact, I had the opportunity to write a report for Nexos magazine here in Mexico, where we explored how eco-anxiety is affecting young Mexican women when deciding whether or not to have children in the future.

Eliezer: At the end of 2021, Yanine conducted a survey of more than one hundred Mexican women. For 78% of them, the climate crisis was a factor they considered when thinking about having children. A quarter of them said it had led them to decide against having kids, and more than half said it was one of their considerations.

Silvia: Other studies point to similar findings. A 2021 study showed that 5 out of 10 young people in Brazil were uncertain about having children because of the climate crisis; in Chile, another study found that number was 7 out of 10.

Yanine: To me, that’s like… How far can eco-anxiety go? It truly has manifestations that significantly influence people’s lives—or at least can.

Silvia: We just heard from Yanine Quiroz and her experience with eco-anxiety. Tell us, how common did you find this type of anxiety to be, and who does it affect the most?

Alejandra Cuellar: Well, eco-anxiety is an interesting phenomenon because it’s relatively new, right? The term itself. It’s been in use since around 2017 when it was first recognized by the American Psychological Association.

Eliezer: That’s Alejandra Cuéllar, editor at Dialogue Earth.

María Mónica Monsalve: What makes this difficult, too, is that it’s not like you go to therapy and the psychiatrist or psychologist simply tells you, “Yes, what you have is eco-anxiety.”

Silvia: And that’s María Mónica Monsalve, a journalist from the América Futura section at El País. Together, they investigated the impact of climate change on mental health.

Alejandra: We went out into the streets and spoke with people from different countries in Latin America. And what we found is that, really, this is a phenomenon that—well, you might think it’s mainly associated with more privileged classes who have access to news, but in reality, people from all social classes feel it, because they’re all exposed to changes in the climate. For example, in Mexico City, I saw very young people who were deeply distressed and anxious about the heat waves because they can no longer practice sports the way they used to. You know? So those are the kinds of examples where you realize—of course, they’re experiencing anxiety because it’s affecting their daily lives. So, it’s interesting how widespread it is, yet in Latin America, it’s not that well-known.

María Mónica: Something that is really evident in Latin America is that the relationship between climate change and mental health is not being studied as rigorously. Most of the scientific literature, most of the research, is coming from high-income countries, or what we sometimes call the Global North. And here, this hasn’t been explored as much. For example, we found a study published in the British Medical Journal in 2021 that examined research on climate change and mental health in low- and middle-income countries. And they found that there were only 58 studies across 11 countries, and only four of those were from Latin America. So, what’s happening is that small seeds of research are sprouting—people from different disciplines are starting to ask these questions—but the broader ecosystem for studying this just doesn’t exist yet in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Silvia: Is that why you felt it was important to cover the connection between the climate crisis and mental health in Latin America? Because of this lack of information?

Alejandra: I’d say that’s exactly where it all started. Both Mónica and I are environmental journalists, so we’re exposed to these stories every day. We’re constantly reading about what’s happening—the different climate events, the disasters. And personally, I remember a day when, after reading the news, I felt just incredibly, incredibly sad, with this overwhelming sense of hopelessness. Like, I didn’t want to do anything. You know, as we say in Colombia, “apaga y vámonos”—just shut it all down and leave—because this is just too much. And I thought, in my publication, we talk about environmental issues, but we don’t talk about the emotions surrounding them. Then I happened to meet Mónica, and she had the exact same concern. When we talked, we thought, “If we’re feeling this way, who else might be feeling it too?” Because one of the things we realized is that there’s a lot of loneliness when it comes to anxiety and mental health struggles. When you’re dealing with a disorder, sadness, or something that makes you uncomfortable, you often think, I feel so alone. I must be the only one going through this. So, we thought, Well, we’re journalists. We have the ability to dig into this topic, investigate who else is experiencing it, how it’s affecting them, and let’s open up this conversation—to really shine a light on this phenomenon.

Silvia: Yanine told us about the heat waves in Mexico last year and how they affected her mental health. These heat waves are becoming more frequent in many countries. But we’re also seeing more natural disasters that are increasingly frequent and devastating due to the climate crisis. How do these disasters impact our health? What did you find in your research?

Alejandra: Well, we started looking specifically at that issue because that’s where most of the research exists. We also examined Hurricane Otis, which struck Mexico in 2023 and hit Acapulco hard.

Archival audio, journalist: “The city of the sun, Mexico’s once-prized tourist gem, has been in decline over the last decade. Now, it’s in chaos.”

Archival audio, woman: “People are frustrated, desperate.”

Archival audio, journalist: “So much pain to heal, so many lessons to learn, and everything to rebuild.”

Alejandra: It was a Category 5 hurricane that caught the population completely off guard. So, it was a useful case study to examine how people are responding. And I found that Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) did intervene with mental health support. I spoke with Betzaida López, who led the effort, and she told me that they arrived a few days after the disaster and managed to speak with many people. One interesting thing is that, in natural disasters, everything becomes difficult to access—roads were closed, for example. So, they used what they called a mobile clinic—essentially a specialized van—and provided both medical and mental health care. If someone came in with a physical issue, they would also ask, Hey, how are you? How do you feel? And she told me that in those first moments, people are deeply affected. Many experience flashbacks—if they hear strong winds, they relive what happened. There are nightmares. Children, in particular, are deeply impacted. So, having this type of intervention is incredibly important. Another interesting thing was that the majority of people who accepted this help were women. Betzaida told me that, generally, men refused it. There’s a lot of stigma. They say, I’m not crazy. I don’t need this help. For them, the priority is physical survival: I lost my house, don’t talk to me about emotions right now.

Eliezer: Mental health interventions in climate disasters are still fairly new. Alejandra explained that after the 2011 earthquake in Sendai, Japan, which killed around 19,000 people, the UN established what’s called the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction.

Alejandra: That’s when these mental health response frameworks were adopted because it became clear that people who experience climate disasters go through trauma. And if it’s left untreated, it can lead to anxiety, depression, suicidal behavior, substance abuse, a lot of alcoholism. So, from that moment, mental health was integrated into disaster response because it became clear that if we don’t address it, it can turn into a much bigger problem.

Silvia: Alejandra says the intervention in Acapulco was small, about 130 consultations. But they also trained local people to be able to address mental health concerns themselves. Because Médecins Sans Frontières and other professionals who come to help right after a crisis don’t stay forever.

Alejandra: And sometimes these are communities with very limited resources. That’s why it’s so important to provide them with the tools to, for example, recognize when someone is experiencing anxiety or suicidal thoughts, not to dismiss them as “crazy” and reject them, but rather to say, “I have a way to understand that this person is going through a mental health issue. I have a resource I can offer—maybe a helpline they can call, maybe a clinic we can visit, or another way to help.” That’s crucial because it means equipping communities themselves with the ability to address these issues and, little by little, breaking down the stigma around them.

Silvia: Right. Did you speak with anyone affected by Otis?

Alejandra: Yes, we spoke with Diana Ruiz. She’s 35 years old. She and her mother lived through the hurricane. They told us they were completely unprepared. It hit while they were in their apartment. They didn’t have time to secure anything. They ended up riding it out in the bathroom, holding onto the door as the wind howled. They described how pieces of the walls were breaking off, how the force of the wind was immense, how terrifying the noise was. It was pure survival mode, trying to save themselves and their home. Then, the door gave way. Diana had a small shop, and everything was destroyed. The next day, it wasn’t just about assessing the damage, it was also about making sure no looters broke in. When I spoke with Diana, it was several months after the hurricane, and she told me that the strongest emotions actually came later. Once the storm had passed, that’s when the sadness, the sense of loss, and the anxiety set in. And the truth is, Acapulco still hasn’t fully recovered from the disaster. The economic impact has been massive. Diana and her mother had to relocate to Mexico City because staying in Acapulco simply wasn’t sustainable. And the mental health struggle continues. They’ve received some support, but what their story really shows is that it’s not enough.

Eliezer: We’ll take a short break and we’ll be right back.

Silvia: We’re back at El hilo. Alejandra and María Mónica wanted to explore the different ways mental health is affected by climate change. One of those ways is what we just discussed: a climate disaster—like Hurricane Otis—leaves deep psychological scars, leading to PTSD, depression, and anxiety…

Eliezer: But they also found that more gradual, slower changes are starting to take a toll on people too.

Silvia: In your research, you talk about how people’s mental health is affected when they witness the destruction of the landscapes they grew up with, the territories that shaped their lives, due to climate change. Tell us about the young Indigenous woman you interviewed who experienced this.

María Mónica: Yes. Her name is Regeane Oliveira. She’s from the Terena Indigenous community. She was part of a study conducted by a Brazilian researcher named Antonio Grande, who wanted to explore both the emotional and cognitive responses Indigenous people have to climate change. She told us that when she left her community to move to the city, because she’s studying medicine, she experienced a deep sense of uprootedness. Back home, she could walk around freely, ride her bike, breathe clean air. Even the food she ate was different. That disconnection triggered severe anxiety. She also gained a lot of weight because of the change in diet. And then, when she went back to visit her family, she started noticing that the landscape, the land itself. was changing too. So instead of coming home and feeling that sense of comfort, of familiarity, she felt like, this isn’t my home anymore. She saw that some rivers were drying up, others had been diverted. And that loss, that transformation, brought her a deep sadness, almost a sense of mourning.

Eliezer: There’s actually a word for that feeling: solastalgia. It was coined by philosopher Glenn Albrecht in 2005 in Australia, after observing the emotions people experienced when they saw their landscapes being altered by mining.

María Mónica: Yeah, and it’s… I mean, the word itself isn’t “beautiful” in the conventional sense, but conceptually, it captures something so powerful. It’s grief. We all understand grief—we grieve when we lose a loved one, when a relationship ends. In Colombia, we even have a word for that heartbreak: tusa. But what this concept highlights is that we, as human beings, can also grieve a lost landscape. And that grief isn’t just metaphorical—it’s something we feel, physically, in our hearts, in our gut, wherever you personally experience emotions. The reason Antonio Grande conducted this study is because Indigenous mental health is increasingly at risk, not just because of climate change but also because Indigenous communities are often marginalized, stigmatized, and denied access to mental health care. The study found that suicide is the second leading cause of death among Indigenous people aged 15 to 29. So, it’s a population already vulnerable to mental health struggles for reasons beyond climate change. And then, climate change comes along and just amplifies everything.

Silvia: Right. Because their connection to the land, to nature, is so profound. It’s fascinating that this study specifically examines how it affects them, because obviously, their experience is different from ours.

María Mónica: Exactly. Because for them, it’s not this human-centered worldview where people are separate from nature. To them, everything is connected, every being matters. The trees, the rivers, the mountains, they’re not just resources, they’re beings. So, when those elements are destroyed, it’s not just an environmental loss; it’s like losing a loved one. And when you think about it that way, the weight of that loss is immense.

Silvia: And in this research, what do they propose to specifically support Indigenous communities?

María Mónica: The study interviewed 20 Indigenous students from two universities in Brazil. They were asked: What could be done to improve Indigenous mental health in the face of climate change? Each participant shared their thoughts, and the responses were mapped out and ranked. One of the most highly prioritized solutions was the protection of Indigenous lands. And what’s so powerful about that is that it’s not just a mental health solution, it’s also a key strategy for addressing climate change and biodiversity loss. Science has already shown that one of the most effective ways to combat climate change is to legally recognize and protect Indigenous territories. And the Indigenous participants in the study said the same thing: This would help us. They also emphasized the importance of preserving Indigenous traditions and knowledge. And then, of course, they spoke about public policies, policies that would bring both mental and physical health services to Indigenous communities, where they are often severely lacking.

Eliezer: Let’s take another short break. When we return, we’ll talk with Alejandra and María Mónica about the challenges Latin America faces in addressing the mental health impacts of the climate crisis.

Silvia: And Yanine Quiroz will share what she does to take care of her own mental well-being. Stay with us.

Eliezer: We’re back at El hilo.

Silvia: You were telling us that, in Latin America, and probably in many other places too, if you go to therapy, they’ll talk to you about anxiety in general, but not specifically about eco-anxiety. So that’s a challenge. But beyond that, what are some of the other challenges Latin America faces in addressing mental health through the lens of climate change?

Alejandra: Well, I think this is something you don’t even need a study to understand. Just living in Latin America, you realize that accessing therapy is only just starting to be seen as normal. Mental health has carried a huge stigma here for a long time. In fact, when I told a friend in Colombia about this research, she said, in Colombia, people would just tell you to get to work. Like, there’s no time for these things. It’s not seen as a priority. It’s the same attitude we saw after Otis, with men saying, I’m not crazy. I don’t need this. This isn’t for me. What’s interesting is that studies show communities already have mental health coping mechanisms, they just aren’t necessarily recognized as traditional psychology or psychiatry. So, maybe there are already tools in place, but there’s resistance to recognizing them as mental health care. But in the end, it’s all about the same thing: acknowledging and processing emotions.

María Mónica: Yes, and despite that— I mean, of course, the community aspect is very important. But the challenge is also huge from within the healthcare sector. That’s where there’s a challenge for educators too. I don’t know, how are we educating young children in schools to understand climate change without creating— how do I put it— the kind of negativity that sometimes pushes people away. Ale and I both recognize that feeling in ourselves, that sense of, “What’s the point anymore? We’re already screwed.” So how do we raise kids who don’t ignore these issues but also don’t get told at seven years old, “Hey, look, it’s all over, don’t even try.”

Alejandra: I think what she’s saying is super important: how we’re raising younger generations. I think that’s a crucial point. And the fact that professionals aren’t trained to talk about emotions or to contextualize these things is another big issue. Something interesting we saw from Good Energy Stories, a media outlet that covers mental health and climate change, is that recognizing this distress, this eco-anxiety, is important to note that it’s not necessarily a bad thing, right? It’s actually a reasonable response to an unprecedented global threat. It’s very comparable to the anxiety people felt during the pandemic, and maybe it’s something that can also push us out of our comfort zones and into action.

Silvia: That’s something I wanted to ask you about because I found the solutions you found to reduce eco-anxiety really interesting. It seems like a virtuous cycle, doesn’t it? Tell us a little about that.

María Mónica: Yeah, well, basically, what psychiatrists, psychologists, and community leaders working on this issue told us is: take action. It sounds super obvious, but in the end, we don’t always do it. Like, so what, you want me to turn off the lights? Plant a tree? Yes, taking action. But of course, these actions, like going to a protest or demanding stronger policies from my government, aren’t going to solve climate change at a global scale. The necessary actions are enormous. But the way I see it, it’s about saving yourself. Taking action gives you a sense of mental peace, a relief that allows you to move forward and do better things.

Alejandra: One of the things I found really beautiful is that, yes, there’s the side of feeling like you’re helping with a problem and contributing to a solution. But there’s also the fact that you’re connecting with others who care about this too. And what you’re creating in those spaces is a different vision of the future. That’s what I find super interesting, because despair and eco-anxiety come from being constantly bombarded with news about the climate apocalypse, right? The predictions all tell us there’s no positive outcome for the planet. Quite the opposite: resources are running out, the air is getting worse. So the idea of the future starts to feel like, wow, my future looks bleak, my future looks hopeless. And by joining a collective initiative, you’re with people who are saying, wait, maybe we’re building the future, and we’re building it in a different way.

Silvia: When you sought help, did you find professionals who made the connection between the climate crisis and what you were feeling?

Yanine: No. It took me a while to realize or acknowledge that what I was feeling was eco-anxiety.

Eliezer: That’s journalist Yanine Quiroz again, whom we heard at the start of this episode.

Yanine: But yeah, by the end of that period, after those heat waves, I finally said: this wasn’t normal. I had never felt that way for so long. And right at the end, the rainy season started, and those rains helped ease my eco-anxiety.

Silvia: On top of her climate-related anxiety, Yanine also had generalized anxiety from stress. She put a lot of pressure on herself at work. She had insomnia. So she started taking antidepressants and seeing a therapist.

Yanine: But she’s not an expert in eco-anxiety. And I do think that’s something I might consider in the future. If I start experiencing those symptoms again, I would probably try to find someone with more experience in helping people with eco-anxiety. Even though, as I mentioned, I’ve covered the topic before in my reporting, and I remember very well what the experts say about how to handle it. But even so, I think I’d still need therapy. Because honestly, just talking— being in therapy— it really does heal you a little.

Silvia: You’re still dedicating your time to these news stories. There could be another heat wave or something else, right? Because we don’t know what’s coming. So how do you take care of yourself now? Besides therapy, what do you do for your mental health?

Yanine: Thank you so much for that question. I think it’s really important. And I’m going to be honest. I’ll share what I really think. I feel like issues of anxiety, and mental health problems in general, at least in Mexico, and I imagine in much of Latin America too, are difficult for people to address because so many lack the resources to access mental healthcare. So sometimes I think about the fact that I’m in a privileged position to be able to afford it. And I think that’s a really important issue: the lack of access to psychological care for most people. And it’s something that’s very much needed.

Eliezer: Yanine says therapy and anxiety medication have been crucial for her. But she also thinks about direct changes. On the one hand, practical things in her daily life, like buying an air conditioner to deal with future heat waves, even though she knows that too is a privilege. On the other hand, she wants to do things that have a broader impact.

Yanine: I’ve also been thinking about something I used to do when I was younger, which is participating in reforestation campaigns.

Silvia: Just what Alejandra and Mónica were talking about: taking action.

Yanine: Because I feel like that’s a way of doing something. That’s definitely something I want to get back into: helping out, being part of volunteer efforts. I think it would help me feel good. And of course, not just for me, it’s something positive for everyone. Reforestation benefits all of us. And I think that, for now, those are the options I see, maybe finding a therapist with more expertise in eco-anxiety or reading a more specialized book on the subject.

Silvia: I really appreciate your honesty and openness in talking about something so personal. My last question would be: why? Why are you willing to talk about this? Why do you think it’s important to give voice to these experiences?

Yanine: I think because eco-anxiety is becoming more and more common, and it’s only going to affect more people in the future. In fact, it already is. Without mental health, we can’t really do anything. We can’t live well, we can’t work, we can’t enjoy life. So it’s crucial to start bringing these issues into public conversations, into media coverage. It’s vital that we start taking these problems seriously— even if you haven’t personally experienced them yet, we should all consider them part of our mental and emotional well-being. And well, thank you, Silvia, for this space.

Silvia: Thank you, Yanine.

This episode was produced by me. It was edited by Eliezer. Fact-checking was done by Desirée Yépez. Sound design by Elías González, with music composed by him and Remy Lozano.

The rest of El hilo’s team includes Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Nausícaa Palomeque, Bruno Scelza, Samantha Proaño, Natalia Ramírez, Juan David Naranjo Navarro, Paola Alean, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Daniel Alarcón is our editorial director. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios. Our theme music was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El Hilo is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Studios. If you value independent, in-depth journalism, please consider supporting us. Latin America is a complex region, and our journalism depends on listeners like you. Visit elhilo.audio/donar to make a donation.

If you’d like to explore today’s episode further, subscribe to our newsletter at elhilo.audio/boletin. We send it out every Friday.

You can also follow us on social media— we’re on Instagram, X, BlueSky, Facebook, and Threads at @elhilopodcast. Leave us your comments there and tag us when you share episodes.

Thanks for listening.